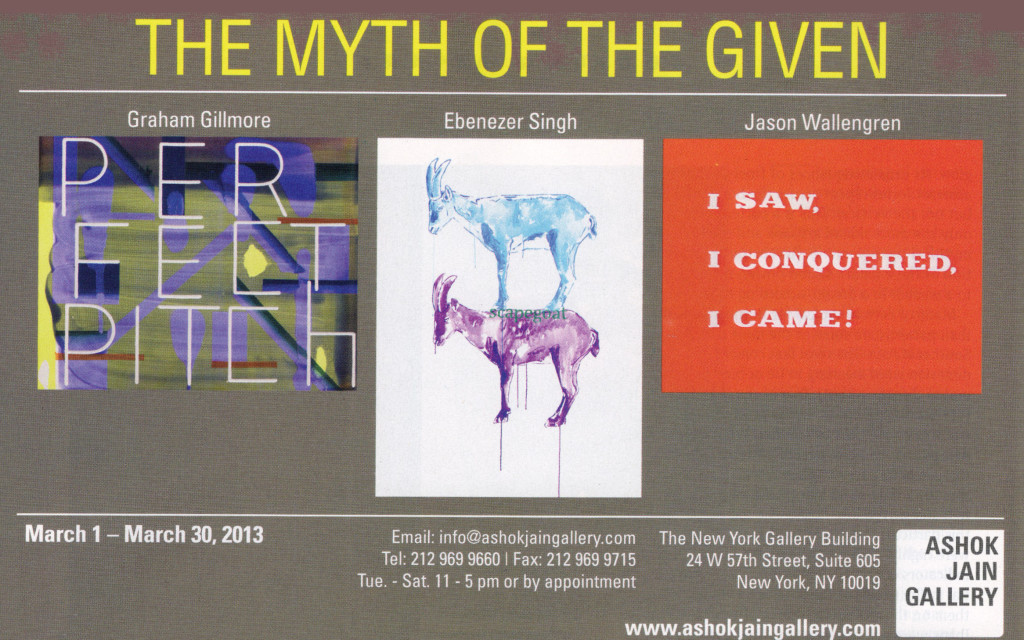

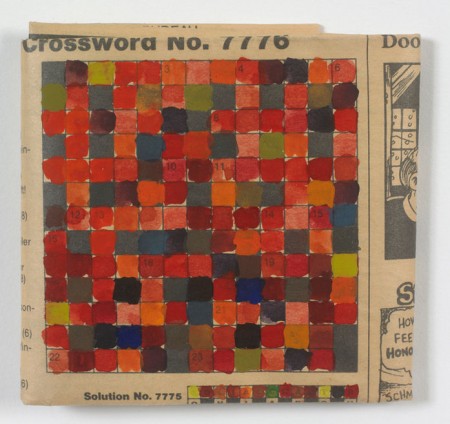

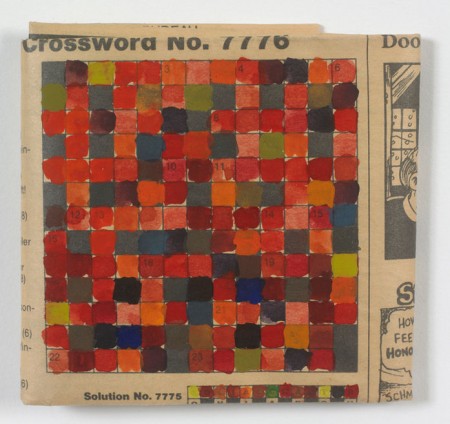

Stephen Dean: “Untitled (Crossword),” 1996–from http://www.artequalstext.com/stephen-dean.

I’m not sure what to say about this. Emily Sessions says interesting things about it and similar pieces by Dean at the website I stole the above from (which has two other Dean works–and, as I’ve mentioned here before, a large quantity of combinations of text and graphics that visual poets should definitely take a look at. The website, which is curated by Rachel Nackman, will soon be updated, I understand.

After reflection, I’ve classified this as a visimage (work of visual art). Whereas Emily Sessions thinks of it as an entrance to an underlying universe of colors, it seems to me an act of–well–desecration; Dean has stolen the crossword grid from anyone who wanted to solve it. His repayment, needless to say, more than makes up for the crime (the crossword, after all, will still be available in many other copies of the newspaper it’s in) by doing what Sessions says it does–although it seems more an overlaying of another universe than an entrance into one, for me. Klee seems to me the magician these magick squares are most in the tradition of. But they enter the day-to-day of social interactivity in a way Klee’s works do not (as Sessions points out).

My thought at this point, as I consider the work for the first time from my critical zone, is that it surprises one out of a readiness to obey rules, pursue a goal, use analysis–in the familiar context of a newspaper’s entertainment section–and into . . . colors, nothing more. Or, to elaborate, into a purely aesthetic experience one can flow unanalytically, goallessly, freely with. Yet, a final, numbered order remains ever-so-slightly visible . . . this newness is safe.

.