I came up with a few more possible layers:

13. The ethical layer. I at first thought ethics would be in the ideational layer, but am now not sure.

14. The anthroceptual, or the human relations layer: character, as opposed to plot. At this point it occurs to me that maybe I ought to link each layer to an awareness or sub-awareness in the cerebrum as I have here. I could also rename the ideational layer the “scienceptual layer.” Will think it over.

15. The allegorical layer, or the only layer those questioning the authorship of Shakepeare’s sonnets are really interested in, the one—if it exists—that arbitrarily attaches real people and places to objects in a poem. Perhaps I should make two layers out of this, the sane allegorical layer, for poems like Spenser’s Faery Queene that use straight-forward allegory, and the psitchotic allegorical layer for poems a lunatic has found to be allegorical.

Actually, this layer should be called the allegorical paraphrasable layer, because it is everything a poem is thought to be under its surface.

Because I have it readily at hand, here’s a rough full paraphrase of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18 I did to show Paul Crowley how sane interpretations of poems are made. Needless to say, I found no allegorically paraphrasable layer.

> 1. Shall I compare thee to a Summers day?

“Would it be a good idea to make a comparison of you to a day in the most pleasant of the four seasons?”

Note that my explication is a paraphrase of the line that takes the DENOTATION of every word into consideration and tries to make linguistic sense. It is concerned primarily with what the surface of the poem means. It ought to deal, too, with any clear-cut connotations of the text it concerns, as well as any secondary meanings, if any. In this case, I find no connotations worth mention, and there is nothing in the line (or, to my knowledge, outside the line–that is, in the background layer, which should be consulted by one making a paraphrase of a poem) to indicate it means anything more than it says.

> 2. Thou art more louely and more temperate:

“You are superior to the summer’s day mentioned in both beauty and temperament.” Ergo, In other words, there’s really no comparison between you and a summer’s day: you’re much the better of the two.

Again, there is nothing in the text to indicate it means anything more than it directly says.

> 3. Rough windes do shake the darling buds of May,

“Unruly, harmful movements of air upset the delicate early blossoms of summer flowers.” Note: May may have been thought a part of summer in Shakespeare’s time. Or May’s buds may still be present by the true beginning of summer.

> 4. And Sommers lease hath all too short a date:

“And that season does not remain in charge of nature for very long: its “contract” to do so is short-term.”

This line and the previous one point out in some detail the defects of a summer’s day, but, implicitly, not of the addressee. There is nothing in them to suggest they mean anything else.

> 5. Sometime too hot the eye of heauen shines,

“There are times when the sun is unpleasantly too high in temperature,”

> 6. And often is his gold complexion dimm’d,

There are also frequent times when the sun is overcast.”

Again, two lines providing further details of what makes the summer’s day inferior to the addressess, who–we are led to believe–has no equivalent of temperatures that are either too hot or not warm enough. And who is never “grey” in disposition.

> 7. And euery faire from faire some-time declines,

“Every good thing is subject to decay, and therefore must lose some of its best qualities. “In summation, each good thing in a summer’s day must eventually retreat from its peak, or lose its best qualities,”

> 8. By chance, or natures changing course vntrim’d:

“the victim of some random event (like being trodden on by some animal) or of the normal way the natural world behaves (turning stormy, for instance).

Ergo, we have two more lines finishing up telling the reader what is wrong with summer–and, it is strongly implied, NOT with the addressee. So far, not a hint that anything other than the surface meaning of the words (beautifully) used is intended.

> 9. But thy eternall Sommer shall not fade,

“Your never-dying prime season, however, won’t ever decline”

> 10. Nor lose possession of that faire thou ow’st,

“or surrender the beauty of appearance and disposition, and other excellences you are in possession of”

Two more straight-forward lines, these ones claiming the addressee will not fade in any manner the way a summer’s day inevitably will.

> 11. Nor shall death brag thou wandr’st in his shade,

“Nor will the ruler of the realm those who die be able to boast that you have entered his realm”

> 12. When in eternall lines to time thou grow’st,

“when in ever-living lines of verse you continue to flourish and perhaps even improve,”

Again, a straight-forward set of lines, these bringing in the speaker of the poem’s second main thought, which is that poetry can make one who is its subject immortal. I admit to not yet knowing exactly what “to time” means, but I believe I have given the most plausible meaning to every one of the other words in the poem.

> 13. So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

“Until such time as human beings are unable to keep alive by taking in air or there are organs sensitive to light,”

> 14. So long liues this, and this giues life to thee,

“the poem you have been reading or listening to will endure, and it will grant you immortality.”

That does it. My explication accounts for every word in the poem except “to” and “time,” and even those can be accounted for as having something to do with resisting what time does to all things. It is also completely plausible AND sufficient, for those with any ability at all to appreciate poetry. (Of course, there’s much more to any poem than an explication of its sanely paraphrasable layer.) To show it has an allegorically paraphrasable layer (or or any other layer containing further meanings of the kind just revealed) requires external evidence of it like the notes of the poet saying such meanings are there, or poems by other poets that seem on the surface like this one but have some significant hidden under-meaning, or permit a second explication that comes up with such a hidden under-meaning that is as smooth, coherent, and reasonably interesting as the primary meaning I’ve just shown the poem indubitably to have.

The third course is the only one you have available, Paul–because we have no notes or anything else relevant from the author or from anyone else to indicate any hidden meanings, nor are there any poems in the language (or any language, so far as I know) that are like the kind of poem you claim this is. I am absolutely sure that you cannot provide an explication that reveals a smooth, coherent, reasonable hidden meaning. In fact, I’m pretty sure you will claim it’s not necessary to–the poet was too complex for any academic or even you fully to explicate.

That would be nonsense, and clear evidence that your interpretation is defective. But not to you. Nor will you ever accept my claim that it is an argument against your interpretation

.

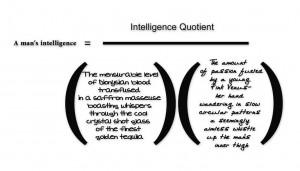

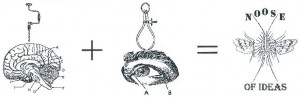

Oops, you may need a magnifying glass. My choice of reproduction seems to be the size above, or four times as large. Anyway, it’s called “A Man’s Intelligence” and may be more informrature–a specimen of informratry–than poetry. Let me quote what it says: “A man’s Intelligence” equals “intelligence Quotient” divided by the product of “The measurable level of Dionysian blood transfused in a saffron masseuse boasting whispers through the cool crystal shot glass of the finest golden tequila” times “The amount of passion fueled by a young pink Venus–her hand wandering in slow circular patterns, a seemingly aimless whistle up the man’s inner thigh.”

Oops, you may need a magnifying glass. My choice of reproduction seems to be the size above, or four times as large. Anyway, it’s called “A Man’s Intelligence” and may be more informrature–a specimen of informratry–than poetry. Let me quote what it says: “A man’s Intelligence” equals “intelligence Quotient” divided by the product of “The measurable level of Dionysian blood transfused in a saffron masseuse boasting whispers through the cool crystal shot glass of the finest golden tequila” times “The amount of passion fueled by a young pink Venus–her hand wandering in slow circular patterns, a seemingly aimless whistle up the man’s inner thigh.”

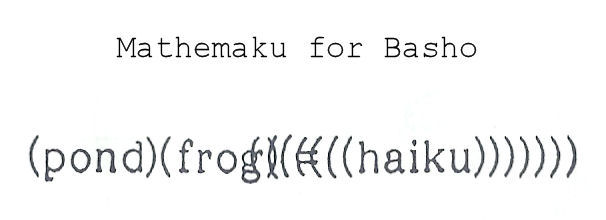

As I announced when I first posted this, I am hoping to publish an antho- logy of mathematical poems, like this one, so if you have one or know of one, send me a copy of it, or tell me about it.

As I announced when I first posted this, I am hoping to publish an antho- logy of mathematical poems, like this one, so if you have one or know of one, send me a copy of it, or tell me about it.

the word ‘poetry’ within the two word term ‘visual poetry’ frames the discussion. we are not saying visual calligraphy nor graphics poetry, nor comix poetry etc.

as long as you focus on your self centered lexicon rather than seek an universal point of viewing, all this is perhaps a talking passed each other.

to continue: because of the steady decline since its peak in the early 1990′s, and because the term visual poetry was coined circa 1965 to break away from the limits of what became concrete poetry, i now prefer the use of sound illumination or illuminated language/s to cover all the visual (must see to fully grasp) use of language that can be composed. the best visual poetry is but a small subset as a result of what took place in the 1990’s. the following is a very abridged outline as to my shift.

just as concrete became cliché, what has become american vizpo/vispo (a term i used since the late 1970′s onward in my correspondence as an abbreviation for visual poetry), much american vispo, since the mid 1990’s attempted take over by a certain click of the language poets, has become neo/retro concrete. many american visual poets aloud themselves to be hypnotized (or consciously gave themselves over) by a perceived center of power of the moment to serve in order to gain recognition and or power, rather than serve the eternal muse of poetry.

vispo is now a cliché. it is no wonder the title of a forthcoming anthology is called the last vispo anthology. the editors themselves not only unconsciously have announced its death but also date its birth as 1950’s concrete movement (: “The Last Vispo Anthology extends the dialectic between art and literature that began with the concrete poetry movement fifty years ago.”) they themselves and those within this particular group consciousness admit they work in a temporal moment without homage to the eternal muse.

visual poetry roots are many thousands of years deep. illuminated language and its ancestral pictorial pictographic petroglyphic images even deeper. those not knowing history are condemned to repeat it. that is obviously true for those cutting history of this form off at 1950.

Interesting entirely unself-centered take on the history of visual poetry, Karl. But, as I point out, your definition of visual poetry is too general. If you disagree with that, you need to present an argument against it. You need to show, for instance, either that poems like “cropse” are visual poems, or why such poems need not be considered visual poems by your definition.

I would add that naming things for political reasons the way you say visual poetry was, retards the search for truth. But “visual poetry” is a good term. It is a good term because it specifies a kind of poetry that is specifically verbal and visual, and not, like concrete poetry, concrete in some other way, such as tactilely. That is why it is in my taxonomy. I would add that almost all concrete poetry is also visual poetry.

‘Visual Poetry is a Poetry that has to be seen.’ can be taken as a definition maybe. But lots of problems here, first of all, written poetry can be seen also. There is a form there and it is not always the same, especially after the free verse. Second, we have to ask maybe where a poem happens? This answer has to be relative. If it is in the paper, well, but what if it is in readers mind, relation to these signs (word, punctuation, structure etc)? If we can define where a poem happens, then we can talk about the eye and visual? But usually a poem happens between reader and the paper, reader “completes” the work as Duchamp mentioned.

Your problem with the definition can be taken care of easily by amending it to “Visual Poetry is a Poetry that has to be seen for full appreciation of its main aesthetic cargo.” The way a conventional poem looks on the page is not part of its main aesthetic cargo. Nor would the calligraphication of its letters be. The problems with it that I point out remain: it would cover too much that is not visual poetry, such as the pwoermd, “cropse,” and illustrated poems (which many artists who make them consider visual poems. A definition should always be as simple as possible, but simplicity rarely works.

As for where a poem happens, it seems clear to me that it happens in the mind. But rationally to define poetry, one needs to consider only what a poem is materially, which is generally word-shaped ink on a page, but which can include visual and other kinds of elements. And, of course, can be in the air as word-shaped sounds.

@Grumman; “The way a conventional poem looks on the page is not part of its main aesthetic cargo” How about thinking Mayakovski and other Russian Formalists and Futurists poems? I know these are not “conventional” but in a certain way they are modern now. How about haiku? and how about arabic or persian poetry for ages that has lot to do with the typography or calligraphy, ideograms etc where language or the sign is not just a carrier for meaning, it has the meaning only by itself. In western thinking these are not may be considered or not taken as main-frame but visual poetry has lots of roots with the “graphic-writing” history of the writing. If you are a verbal poet or as Ong say “verbomotor poet” these has minor importance but other way, every structural element has critical importance i guess. And how can we be sure that cargo, can be carried easily by any means and chance of the Language? Is poetry that good at that kind of information (communication)?

I think it’s a matter of a case by case decision whether a given poem’s aesthetic cargo is visual enough to make the poem a visual poem. I simply subjectively do not feel calligraphy (in most cases) does so. It’s decorative only. Spacing in poems isn’t enough, either, in my subjective view. I don’t see how haiku are visual. Chinese ideagrams may seem very visual to westerners but are essentially composed of symbols that are read, not seen.

As for language’s ability to carry an aesthetic cargo, I assume without the help of its visual arrangement and decoration, I simply subjectively believe that words can carry huge amounts of meaning and that in a good poem that meaning makes things like calligraphy minor.

One has to make subjective decisions like that or give up defining things. It seems to me that you are basically calling for a definition of visual poetry too broad to be useful. What isn’t visual poetry if haiku are or, apparently, any hand-written poem is?

i would have to say, the use of the phrase ‘eternal muse of poetry’ seems ridiculous here. taking wide sloppy swings at people you do nothing but miss and waste our time.

karl kempton sevişelim mi?

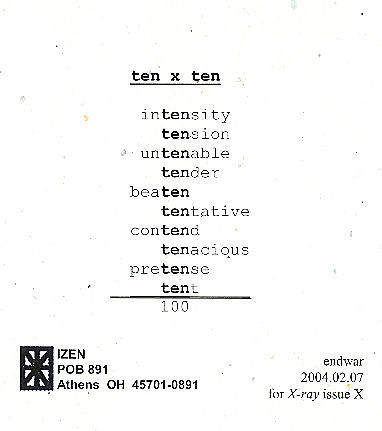

Concrete poem represents deep feeling