Yesterday I came across a website new to me I thought interesting. It’s here, where there’s a box you can type any author’s name into. It lists a huge number of authors all the way down to my low level of visibility and indicates, as you will see, how many copies of the authors are in all the libraries belong to the organization running the site. Mostly university libraries, I suspect, since I doubt that aside from them more than the Library at Charlotte High, where I subbed for fourteen years and was good friends with the head librarian, has anything of mine, assuming even the Charlotte High library does.

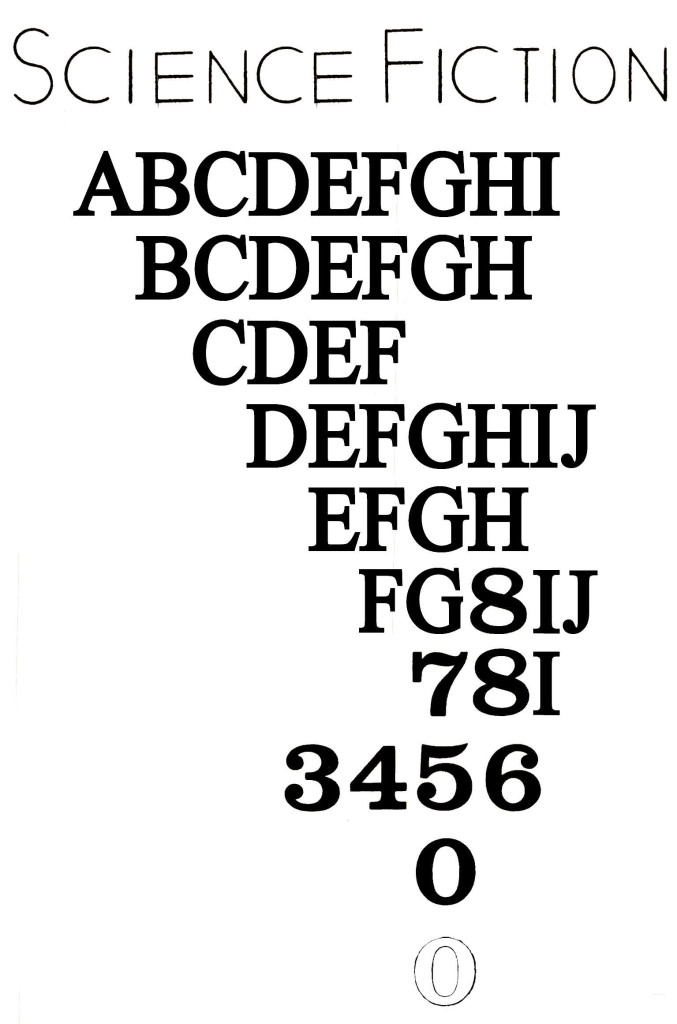

My pal Richard Kostelanetz has almost as many pages there as I have individual entries. No surprise. I mention it for three reasons–(1) to gain status with the claim that he’s a pal of mine (because I’m a real statooznik, as everyone knows); (2) because his most widely-held publication (in over a thousand libraries) is Dictionary of the Avant Gardes that I’m in, too (!), which encourages me to believe posterity may come across me even fifty years from now; and (3) to put the “Audience Level” of my works in perspective by noting that it’s around 90 on a scale of 100, his around 50, so I can pretend my stuff is vastly more intelligent than his (although I recognize that my work is just much less clear than his–and mainly experimental poetry versus well-written non-academic prose).

I’m a little bothered that Velocity had a lower rating than Of Manywhere-at-Once, which I tried my best to be at the level of the average reader. I find it pretty funny that apparently A StrayngeBook is at a higher level than Richard’s work. But, ho, one of Richard’s works got a hundred! None of mine did. I should do something about that . . .

Overview

Works: 46 works in 50 publications in 1 language and 226 library holdings

Most widely held works by Bob Grumman

Visual poetry in the Avant Writing Collection by Ohio State University ( Book ) 1 edition published in 2008 in English and held by 78 WorldCat member libraries worldwide

Writing to be seen : an anthology of later 20th century visio-textual art ( Book ) 2 editions published in 2001 in English and held by 25 WorldCat member libraries worldwide

Writing to be seen : an anthology of later 20th century visio-textual art ( Book ) 1 edition published in 2001 in English and held by 22 WorldCat member libraries worldwide

Of manywhere – at – once by Bob Grumman ( Book ) 2 editions published between 1991 and 1998 in English and held by 9 WorldCat member libraries worldwide Early in 1983 … [the] severely middle-aged poet/critic [author] began writing a 14-line poem (a sonnet, in fact). this … book tells the story of his 5-year struggle to get that poem right. More than that, however, it is a full-scale investigation of poetics, with numerous side-musings into poems by such masters as Shakespeare, Keats, Cummings, Pound, Yeats, Roethke and Stevens–as well as such contemporaries as Karl Kempton, G. Huth, Crag Hill, Bob Grenier and John M. Bennett. It is, in fact … [a] large-scale discussion of poetry to cover all extant varieties of it, including current visual poetry, alphaconceptual poetry and “language poetry.” Anyone interested in what words, or even mere letters, can say and be at their best, should find this book of … value …-Back cover

Just feet by John M Bennett ( Book ) 1 edition published in 1994 in English and held by 9 WorldCat member libraries worldwide

Swelling by John M Bennett ( Book ) 1 edition published in 1988 in English and held by 7 WorldCat member libraries worldwide

A straynge book by Bob Grumman ( Book ) 1 edition published in 1987 in English and held by 6 WorldCat member libraries worldwide

SpringPoem No. 3,719,242 by Bob Grumman ( Book ) 1 edition published in 1990 in English and held by 5 WorldCat member libraries worldwide

Vispo auf deutsch : an anthology of verbo-visual art in German ( Book ) 1 edition published in 1995 in English and held by 5 WorldCat member libraries worldwide

An April poem by Bob Grumman ( Book ) 1 edition published in 1989 in English and held by 4 WorldCat member libraries worldwide

Greatest hits , 1966-2005 by Bob Grumman ( Book ) 1 edition published in 2006 in English and held by 4 WorldCat member libraries worldwide

Ghostlight by G Huth ( Book ) 1 edition published in 1990 in English and held by 4 WorldCat member libraries worldwide

Of manywhers-at-once : ruminations from the site of a poem’s construction by Bob Grumman ( Book ) 1 edition published in 1990 in English and held by 3 WorldCat member libraries worldwide

A straynge catalogue by Bob Grumman ( Book ) 1 edition published in 1989 in English and held by 3 WorldCat member libraries worldwide

Velocity ( ) in English and held by 3 WorldCat member libraries worldwide

Shakespeare & the rigidniks : a study of cerebral dysfunction by Bob Grumman ( Book ) 2 editions published in 2006 in English and held by 3 WorldCat member libraries worldwide

Dirges by Bob Grumman ( Book ) 1 edition published in 2002 in English and held by 2 WorldCat member libraries worldwide

A selection of visual poems by Bob Grumman ( Book ) 2 editions published between 1999 and 2005 in English and held by 2 WorldCat member libraries worldwide

Between : sequence 1 by J. W Curry ( Book ) 1 edition published in 1989 in English and held by 2 WorldCat member libraries worldwide

This is visual poetry : chapbook by Bob Grumman ( Book ) 1 edition published in 2010 in English and held by 2 WorldCat member libraries worldwide

Audience Level Kids General Special Audience level: 0.93 (from 0.47 for Velocity … to 1.00 for Swelling / …) (Note: Swelling is by John Bennett, but I probably wrote an intro for it; it’s one of my press’s publications. So it doesn’t mean I have anything with a 100 audience level rating.)

Second Page

11 works in 11 publications in 1 language and 16 library holdings

Roles: Editor

Most widely held works by Bob Grumman

Cryptographiku 1-5 by Bob Grumman ( Book ) 1 edition published in 2003 in English and held by 2 WorldCat member libraries worldwide

Poemns [sic] by Bob Grumman ( Book ) 1 edition published in 1997 in English and held by 2 WorldCat member libraries worldwide

Poem, demerging by Bob Grumman ( Book ) 1 edition published in 2010 in English and held by 2 WorldCat member libraries worldwide

Mathemaku, 6-12 by Bob Grumman ( Book ) 1 edition published in 1994 in English and held by 2 WorldCat member libraries worldwide

April to the power of the quantity Pythagoras times now : a selection of mathemaku by Bob Grumman ( Book ) 1 edition published in 2008 in English and held by 2 WorldCat member libraries worldwide

Mathemaku, 1-5 by Bob Grumman ( Book ) 1 edition published in 1992 in English and held by 1 WorldCat member library worldwide

Pnd by Bob Grumman ( Book ) 1 edition published in 1987 in English and held by 1 WorldCat member library worldwide

Vispo auf deutsch : an anthology of verbo-visual art in German ( Book ) 1 edition published in 1995 in Undetermined and held by 1 WorldCat member library worldwide

Mathemaku 13-19 by Bob Grumman ( Book ) 1 edition published in 1996 in English and held by 1 WorldCat member library worldwide

Mathemaku no. 2 by Bob Grumman ( Book ) 1 edition published in 1988 in English and held by 1 WorldCat member library worldwide

Audience Level 1 Kids General Special Audience level: 0.87 (from 0.00 for Writing to … to 1.00 for Poem, deme …) (Ah, good, I do have a book with a top audience level rating! It will be interesting to find out its audience level rating in fifty years. Much lower, I’m sure.)

WorldCat IdentitiesRelated Identities • Bennett, John M. plus • Ohio State University Libraries Avant Writing Collection plus • Sackner, Marvin A. 1932- plus • Ohio State University Libraries Rare Books and Manuscripts Library plus • Hill, Crag plus • Stetser, Carol plus • American Visual Poets’ Cooperative plus • Runaway Spoon Press Publisher plus • Berry, Jake plus • Ackerman, Al

Later Note: I found out you can click an individual title and find some but not all the libraries with copies of it. As expected, in my case, it’s just university libraries wanting to have complete collections of ephemera–just in case.

.

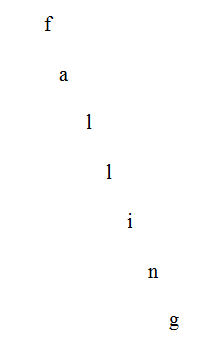

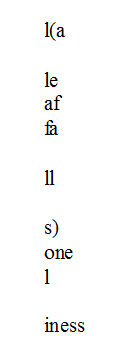

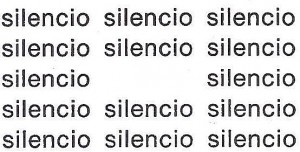

Hmmm . . . . all leaves in fall.

Was this one of the response to Dan Waber’s “Fall leaves” project?

– endwar

I’m away from the files in my main computer so can only tell you it was a response to one project of Dan’s, probably the one you mention. Not sure, though, It had to do with work by bp Nichol, though.