Archive for the ‘Discussion of a Poem’ Category

Entry 1611 — Interpretation of Poems, Part 2

Saturday, October 25th, 2014

I came up with a few more possible layers:

13. The ethical layer. I at first thought ethics would be in the ideational layer, but am now not sure.

14. The anthroceptual, or the human relations layer: character, as opposed to plot. At this point it occurs to me that maybe I ought to link each layer to an awareness or sub-awareness in the cerebrum as I have here. I could also rename the ideational layer the “scienceptual layer.” Will think it over.

15. The allegorical layer, or the only layer those questioning the authorship of Shakepeare’s sonnets are really interested in, the one—if it exists—that arbitrarily attaches real people and places to objects in a poem. Perhaps I should make two layers out of this, the sane allegorical layer, for poems like Spenser’s Faery Queene that use straight-forward allegory, and the psitchotic allegorical layer for poems a lunatic has found to be allegorical.

Actually, this layer should be called the allegorical paraphrasable layer, because it is everything a poem is thought to be under its surface.

Because I have it readily at hand, here’s a rough full paraphrase of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18 I did to show Paul Crowley how sane interpretations of poems are made. Needless to say, I found no allegorically paraphrasable layer.

> 1. Shall I compare thee to a Summers day?

“Would it be a good idea to make a comparison of you to a day in the most pleasant of the four seasons?”

Note that my explication is a paraphrase of the line that takes the DENOTATION of every word into consideration and tries to make linguistic sense. It is concerned primarily with what the surface of the poem means. It ought to deal, too, with any clear-cut connotations of the text it concerns, as well as any secondary meanings, if any. In this case, I find no connotations worth mention, and there is nothing in the line (or, to my knowledge, outside the line–that is, in the background layer, which should be consulted by one making a paraphrase of a poem) to indicate it means anything more than it says.

> 2. Thou art more louely and more temperate:

“You are superior to the summer’s day mentioned in both beauty and temperament.” Ergo, In other words, there’s really no comparison between you and a summer’s day: you’re much the better of the two.

Again, there is nothing in the text to indicate it means anything more than it directly says.

> 3. Rough windes do shake the darling buds of May,

“Unruly, harmful movements of air upset the delicate early blossoms of summer flowers.” Note: May may have been thought a part of summer in Shakespeare’s time. Or May’s buds may still be present by the true beginning of summer.

> 4. And Sommers lease hath all too short a date:

“And that season does not remain in charge of nature for very long: its “contract” to do so is short-term.”

This line and the previous one point out in some detail the defects of a summer’s day, but, implicitly, not of the addressee. There is nothing in them to suggest they mean anything else.

> 5. Sometime too hot the eye of heauen shines,

“There are times when the sun is unpleasantly too high in temperature,”

> 6. And often is his gold complexion dimm’d,

There are also frequent times when the sun is overcast.”

Again, two lines providing further details of what makes the summer’s day inferior to the addressess, who–we are led to believe–has no equivalent of temperatures that are either too hot or not warm enough. And who is never “grey” in disposition.

> 7. And euery faire from faire some-time declines,

“Every good thing is subject to decay, and therefore must lose some of its best qualities. “In summation, each good thing in a summer’s day must eventually retreat from its peak, or lose its best qualities,”

> 8. By chance, or natures changing course vntrim’d:

“the victim of some random event (like being trodden on by some animal) or of the normal way the natural world behaves (turning stormy, for instance).

Ergo, we have two more lines finishing up telling the reader what is wrong with summer–and, it is strongly implied, NOT with the addressee. So far, not a hint that anything other than the surface meaning of the words (beautifully) used is intended.

> 9. But thy eternall Sommer shall not fade,

“Your never-dying prime season, however, won’t ever decline”

> 10. Nor lose possession of that faire thou ow’st,

“or surrender the beauty of appearance and disposition, and other excellences you are in possession of”

Two more straight-forward lines, these ones claiming the addressee will not fade in any manner the way a summer’s day inevitably will.

> 11. Nor shall death brag thou wandr’st in his shade,

“Nor will the ruler of the realm those who die be able to boast that you have entered his realm”

> 12. When in eternall lines to time thou grow’st,

“when in ever-living lines of verse you continue to flourish and perhaps even improve,”

Again, a straight-forward set of lines, these bringing in the speaker of the poem’s second main thought, which is that poetry can make one who is its subject immortal. I admit to not yet knowing exactly what “to time” means, but I believe I have given the most plausible meaning to every one of the other words in the poem.

> 13. So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

“Until such time as human beings are unable to keep alive by taking in air or there are organs sensitive to light,”

> 14. So long liues this, and this giues life to thee,

“the poem you have been reading or listening to will endure, and it will grant you immortality.”

That does it. My explication accounts for every word in the poem except “to” and “time,” and even those can be accounted for as having something to do with resisting what time does to all things. It is also completely plausible AND sufficient, for those with any ability at all to appreciate poetry. (Of course, there’s much more to any poem than an explication of its sanely paraphrasable layer.) To show it has an allegorically paraphrasable layer (or or any other layer containing further meanings of the kind just revealed) requires external evidence of it like the notes of the poet saying such meanings are there, or poems by other poets that seem on the surface like this one but have some significant hidden under-meaning, or permit a second explication that comes up with such a hidden under-meaning that is as smooth, coherent, and reasonably interesting as the primary meaning I’ve just shown the poem indubitably to have.

The third course is the only one you have available, Paul–because we have no notes or anything else relevant from the author or from anyone else to indicate any hidden meanings, nor are there any poems in the language (or any language, so far as I know) that are like the kind of poem you claim this is. I am absolutely sure that you cannot provide an explication that reveals a smooth, coherent, reasonable hidden meaning. In fact, I’m pretty sure you will claim it’s not necessary to–the poet was too complex for any academic or even you fully to explicate.

That would be nonsense, and clear evidence that your interpretation is defective. But not to you. Nor will you ever accept my claim that it is an argument against your interpretation

.

Entry 1541 — Thoughts Concerning Entry 1540

Sunday, August 17th, 2014

Nice to see that more people are visiting my Journal of Mathematics and the Arts article than just the forty or fifty to whom I sent free links to it–75 yesterday morning. I’m hoping for a hundred!

A few follow-ups to yesterday’s entry. First about the poem. As some of you will realize, the quotient is one of my “poemns”–i.e., one of the haiku in my 1966 collection, poemns. Two questions occurred to me as I used it: (1) how does the poem’s existence now in two rendering affect its cultural value? and (2) should I make more long divisions using various poemns, perhaps all of them?

I hope having two versions of my poem is a plus. The first is still important as a stand-alone because a simplification toward intensification at the expense of complexity; the second manywheres far beyond but with, I believe, the loss of maximal intensification. In its relocation in a long division, the poemn’s connotative value is diminished, but certain of its specific connotative possibilities are strengthened. I think I would like them read far apart from each other, the poemn first, most happily without the reader’s being aware of its use elsewhere.

I just laughed a bit to myself at the thought that I might now make a third version.

Further note: I consider poemns a collection of visual haiku, but my little boy (me at Harbor View, age 11) is not in a visual poem, but a cryptographiku (my very first one), that being a kind of infra-verbal poem that makes significant aesthetic use of an encrypted text, and infra-verbal poem being (as you all know) a poem in which what counts is what happens inside words.

I also want to say a bit about my declaration that my poem is a major one (as is my poemn–a major poem within a major poem, by gum). That I need all the encouragement I can get, including self-encouragement is one reason for it. Another is the hope mentioned yesterday that some one would challenge, intelligently challenge, me on it. That would have the value of publicizing it, and perhaps educating some people about it. But–most important for me, I swear–I might find out something that helps me as a poet. (I almost never fail to learn something that helps me as a poet from thoughtful feedback, even very mistaken feedback, and am always surprised when that happens.) I would also get a better sense of how my poems are coming across to others, and I truly want to know that because while simply the satisfaction I when I make a poem I like is enough for me, I also want others to enjoy it–which is the main reason by far that I make my poems public. Benefiting materially from a poem would be very nice (I assume, from what little I know of it) but, as I often say, I’d a billion times prefer to make a poem and two or three others like without getting a cent for it than a poem I think tenth-rate but others like enough to give me–well, a Nobel prize for (the money that comes with it being about all that I’d be interested in).

.

Entry 1506 — Another Lesson in Poetics

Sunday, July 6th, 2014

I was thinking about the poem below after posting it yesterday, recalling that I was confused then, at the age of 25, and until I was in my late thirties about what a metaphor was, which is ironic, because my poem is, as a whole, a perfect metaphor:

Its metaphor (as I now define the term) is the sentence (and its overflow) which makes up the entire poem. The metaphor’s referent is the boy on the swing. The two together make up what I call a “metaphormation”–but am agreeable to having others call it a metaphorical expression. My long-time confusion about what metphors was due to my hearing or reading people calling both what I now call a metaphor and what I call a metaphormation metaphors.

Here, though I hope you don’t need it, is a paraphrase of the poem: a small boy at the height of his swings on a playground swing breaks the law of gravity like a sentence continuing beyond its period breaks the rules of grammar. The idea of making expressive us of punctuation marks I got from Cummings–although I’ve never decided whether he ever intentionally made linguistically-expressive use as well as visually-expressive use of them. I’d enjoy being the first to do this, if it’s possible I am, but would not consider it an accomplishment anywhere near the level of Cummings’s invention–certainly for America–of infraverbal poetry, by which I mean his being the first to make it, effectively, seriously, in more than a few scattered poems.

.

Entry 1585 — BG, Master American-Haiku-Critic

Sunday, June 15th, 2014

from a post to NowPoetry from Jesse Glass, whom I consider a superior knower of things Japanese although he is diffident about it, with my thoughts interspersed:

Hokku

Bits of song—what else?

I, a rider of the stream,

Lone between the clouds.

from an interesting old anthology titled The New Poetry eds. Harriet Monroe and Alice Corbin Henderson

* * *

Jesse: “I think the first line exhibits the Homer Simpson “d’oh!” factor to a high degree. The other two lines are fine.”

Me: “I discur about the first line, Jesse–my interpretation of this American haiku (because no longer in Japanese) is something like: ‘here I am again with nothing but a trivial poem–me–up there like a god, alone in the clouds.’ Ergo, the first line sets up the second: image of bits of anybody song in tension with some great stream in the sky only someone vastly above (in many senses) ‘bits of song’ can ride. Resolution of what seems to me a sort of metaphor: bits of song equal anything in Nature, however magnificent–with the implication that the speaker of the poem is a fool, or a slyly-ironic non-fool.

“Of interest to me is the fantasy of the second and third lines. Are traditional haiku allowed to indulge in sheer fantasy, Jesse? My impression is that they aren’t, but I’m not sure. I, of course, am all for allowing it. In any case, the rider in the sky’s is definitely metaphoric, and I know metaphors were banned–although I contend that just about all the best elderly haiku had juxtaphors, my name for implicit metaphors.

“Note: I take “hokku” to be a synonym for “haiku,” or too near to consider a different kind of poem. The Hokku above in American is a haiku, for me. But you might explain what the Japanese mean by ‘hokku,’ Jesse; I’m pretty sure you have a better idea of that than I.”

From: Anny Ballardini

Heaps of black cherries

glittering with drops of rain

in the evening sun

Richard Wright

Me: “This is a poor haiku because containing only one image, albeit a pleasant enough one.”

stole two red cherries

expensive in plastic baskets

under the electric light

me

Me: “This I like I lot. Either Wright caught on to hakuitry by the time he wrote it, or got lucky. It’s still very close to being just one image, but I interpret there to be two sets of images in effective hakuic tension with each other: the cherries under the bright light, and the boy, distant from them in space and mood, the cherries cheerful, the boy guilty–or proud; and the cherries in plastic baskets and the boy with two stolen cherries under the electric light, very visible to the authorities (standing out, ion fact, the way the printed word, ‘me,’ does on the page.

“Comments welcome, especially counter-comments. Show where I’m off, and you will qualify to be a master American-haiku-critic, first–or at least second-class.”

BG

Note from BG, the racist: I wish there were fewer streets named after Martin Luther King and more named after Richard Wright. (If I weren’t a racist, I’d want streets named after George Washington replaced with streets named after Richard Wright. No, name those after E. E. Cummings or Wallace Stevens or Theodore Roethke. Actually, we need no streets named after greater writers, because books of their work, or the electronic equivalent, are more than streets-enough for them.

Question from my hydrocodoned mood: what other writer in our country has written as entertaining and interlekshoolly-valuable a little essay in the past decade as the above? Or is as lovable (on paper)?(I took the hydrocodone to assure I did meaningful work on the essay regarding beauty I’ve been working on for months! I haven’t yet gotten to it almost two hours after taking my hit. Now I may.*

*It’s lucky I’m as old as I am. It’s scary how fast my lovability is increasing nowadays. If I were only twenty, it’d explode before I was fifty, and kill millions.**

**Aren’t the opponents of drug-addiction lucky I’m giving them so much good evidence against hydrocodone with stuff like this?***

*** Note, too, how the hydrocodone is keeping me from my essay on Beauty. Hmm, maybe that’s what’s good about it. Except that it will not keep me from it any longer. Later!

.

Entry 1362 — A Haiku Review

Wednesday, February 5th, 2014

For today, a haiku review first appearing in Modern Haiku, then reprinted in my From Haiku to Lyriku. It’s here because I needed something to post and pages 86 and 88 happened to be the pages I turned to when I opened that to grab something. But I like my haiku reviews, even though they never made me famous.

.

Entry 1348 — “Nymphomania”

Wednesday, January 22nd, 2014

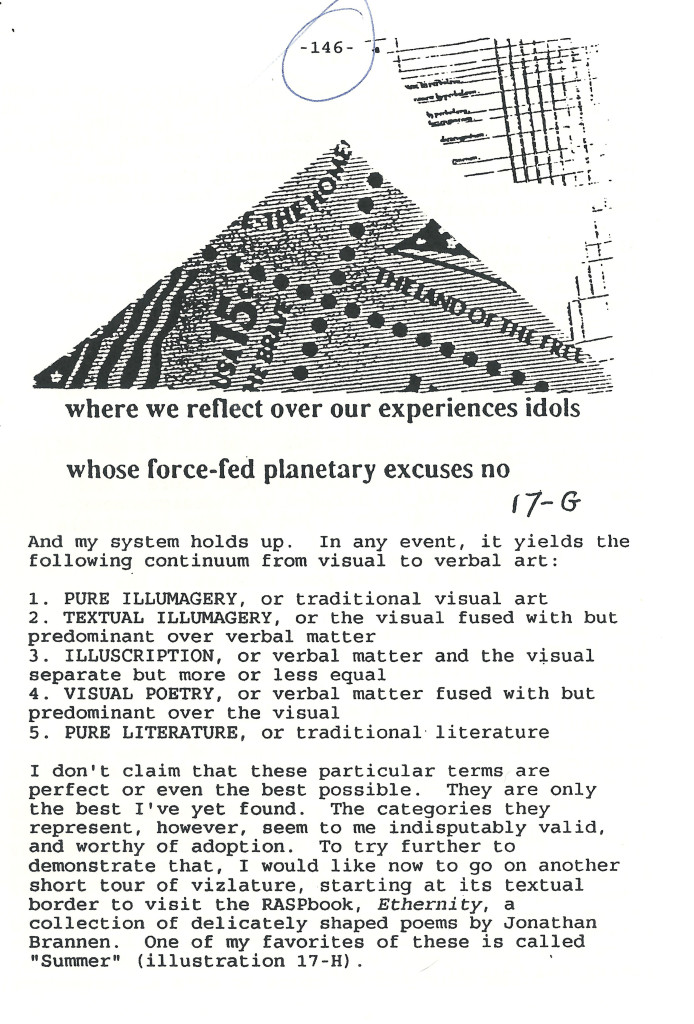

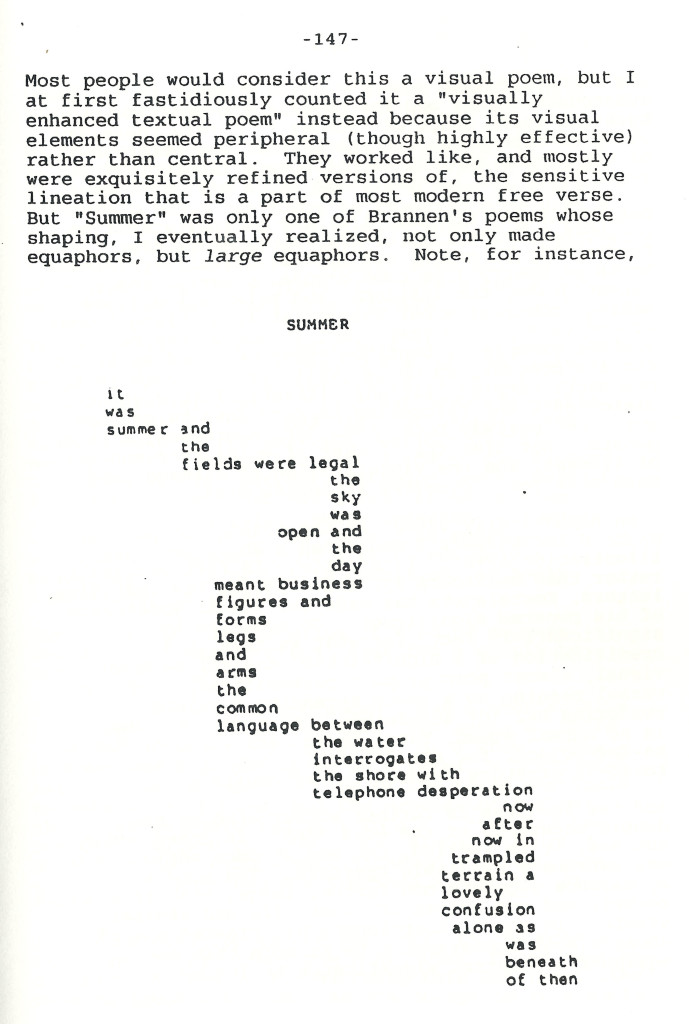

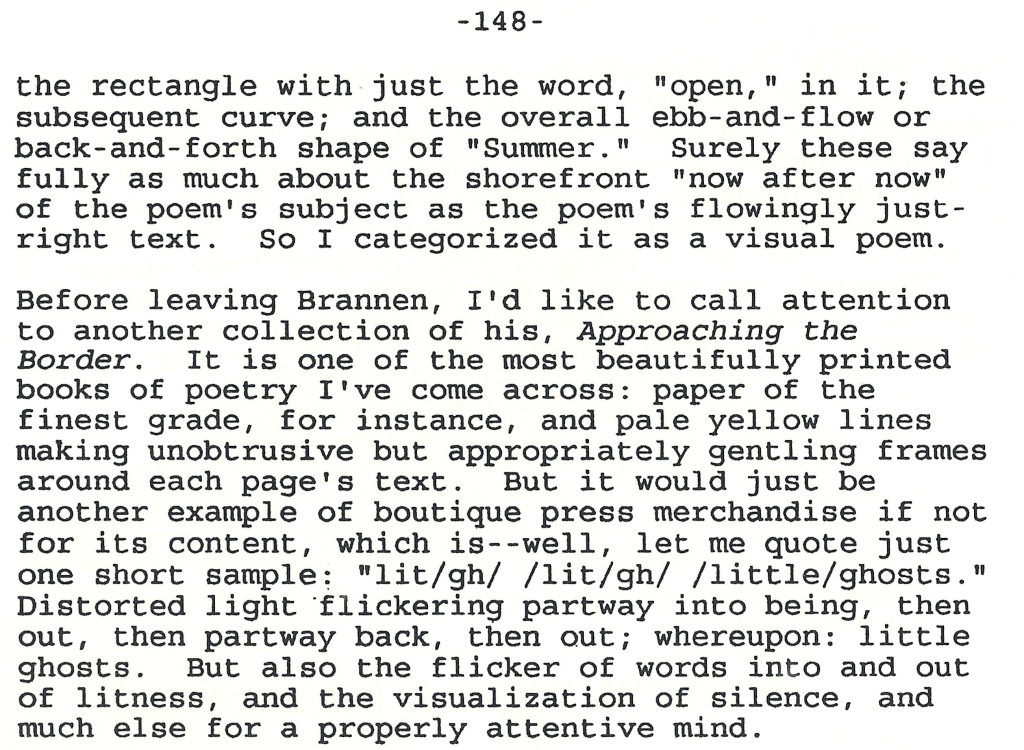

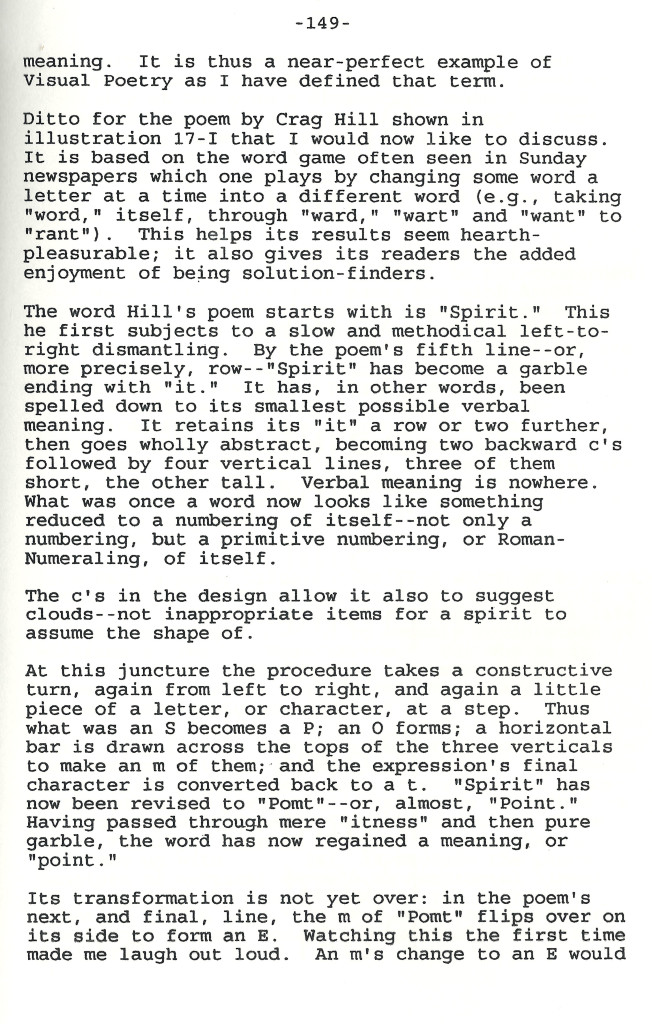

All I have to say about yesterday’s entry is that the work at the top of the uppermost page is by Harry Polkinhorn. It’s a frame from Summary Dissolutions, a sequence of his my Runaway Spoon Press published sometime in the eighties. I also wanted to note that the very rough taxonomy presented hasn’t changed except that I now call “illumagery,” by another name: “visimagery.” For this entry I just have something more from Of Manywhere-at-Once:

Note: the text above directly follows my comments on Jonathan Brannen’s poem.

.

Entry 1347 — Another Late Entry

Tuesday, January 21st, 2014

My absentmindedness is getting worse, it would seem, although it was pretty bad to begin with. Anyway, here is yesterday’s entry, just thrown together a day late. It’s some pages from Of Manywhere-at-Once that I don’t have time to comment on:

.

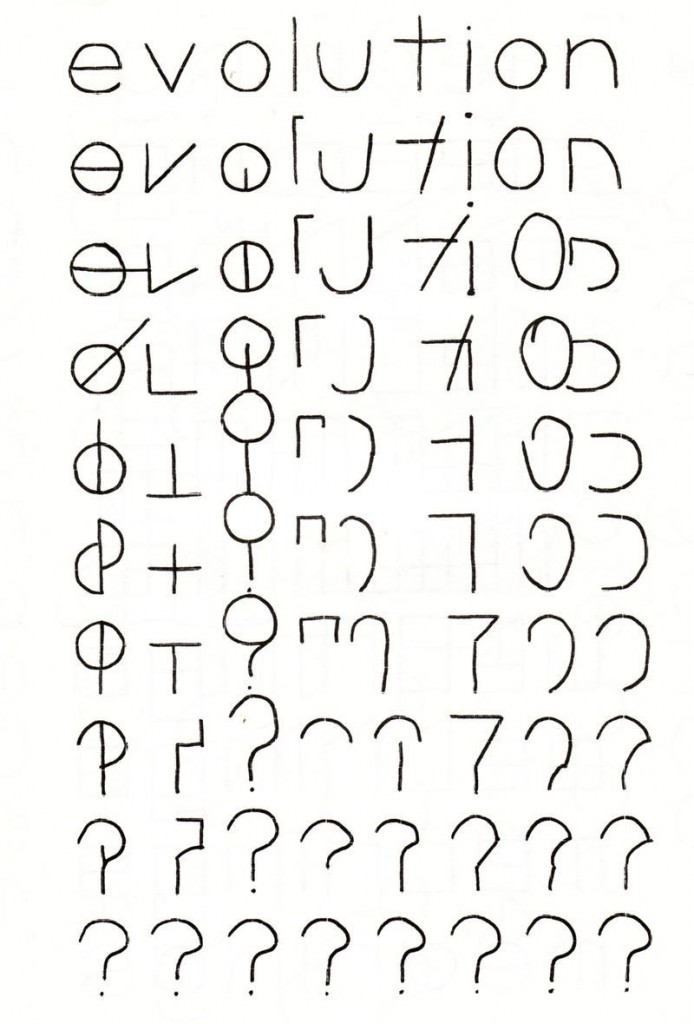

Entry 1345 — Excerpts from a Masterpiece

Sunday, January 19th, 2014

The masterpiece is my Of Manywhere-at-Once. I suddenly had the brilliant thought of taking care of blog entries for the next few days with full pages of the third edition of it (the Runaway Spoon Press, 1998–the first edition was published eight years earlier, with this section the same as it is here). For once, laziness is not my reason for doing this. What is, is a need to concentrate of an essay I’m working on whose deadline will soon be on me. So: here are three consecutive pages from my book, left as is:

I think I have one or two copies of my available for sale, but they are now collectors’ copies, so I have to ask for a hundred bucks for one. But I will sign it. Its buyer will also have the satisfaction of having helped a poet keep from bankruptcy. (I’m serious–otherstreamers ought to ask for compensation at least equal to a thousandth of what celebrated tenth-raters get for absolute crap. And what can we lose since we can’t get even the cost of our raw materials for anything?)

As I posted the second of my three pages, I thought to myself (as opposed to thinking to someone else–ain’t the Englush lingo funny at times?) I really ought to save my second and third pages for my next two entries. Being nice to my readers triumphed, though, so they are all here. I do plan to use them again tomorrow. I have second thoughts about at least one part of my text, and first thoughts about what I think about it, and what was going on in my life at the time I wrote it.

.

Entry 1343 — “(Music Ahead)”

Friday, January 17th, 2014

“The Quantity, Music Ahead, to the Power of Balloons,” as I call the little graphic I posted here yesterday, is a recently-revised visiomathematical detail from my “Long Division of Creativity.” It had been just “balloons.” I’m about to write a commentary on the poem it’s in for an essay I’m doing for the Journal of Mathematics and Art, that will make my reputation. This detail, added to a graphic I made to represent the blossoming of spring–although it can be many other things as well, or instead, equals “Creativity.” By itself, it’s “music:” with an exponent representing good cheer, celebration, buoyancy, etc., not to mention balloons. Note the colon: the G-clef does not quite represent music, but music coming up. This particular G-clef is taken from another poem, of mine, and is an often-used symbol of mine for “music:” (and I don'[t mind its being taken to symbolize music as well, in fact, prefer it to be).

A poem-within-a-poem . . . that itself contains a (very minor) poem-within-a-poem, the word, “balloons,” in color. I put it there mainly because I wanted something in the poem that was highly accessible.

.