Entry 621 — Evolution of Style

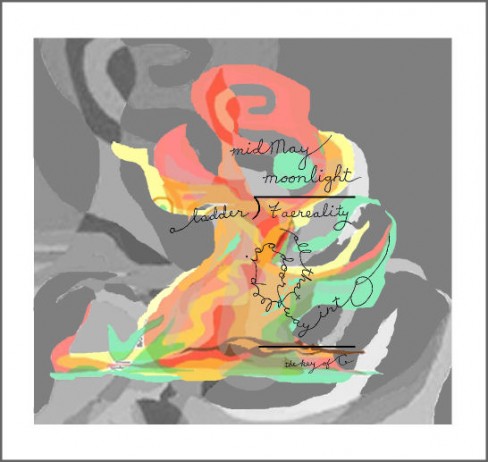

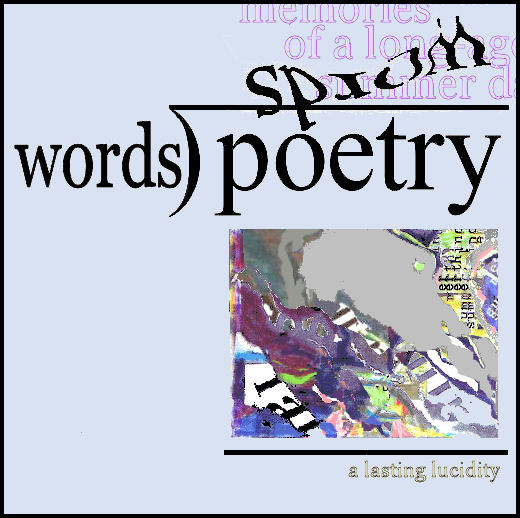

One of my works that I was particularly pleased with when I came across it while backing up blog entries was the following:

I have one problem with this: my only version of it is a low-resolution jpg, which I don’t know how to convert to high-resolution tif, except by simply redoing it. Any suggestions from anybody out there who knows more than I do about this kind of thing?

I didn’t re-post it only to ask for help, or because of how much I like it, but as an example of how my work as a poet has evolved. Actually, I want to show that it has evolved. That’s because Paul Crowley, the nut I most argue with on the Internet about who wrote the works of Shakespeare, seems not to believe that a poet’s style, or way of making art, evolved once he’s past his apprenticeship. Of course, he will claim I’m not a poet, and that the evidence I’m about to produce to show my evolution indicates only trivial changes, not anything like genuine evolution. I enjoy talking about my work, and analyzing any poem, so will go ahead with my demonstration, anyway.

First of all, I should state my claim: it is that over the past couple of years, my style as a poet has evolved appreciably, and that this poem illustrates it.

(1) I only began using cursive ten or fewer years ago, and never for more than a word or two. This poem and two others have all or most of their texts in cursive. Because the difference in expressiveness between print and cursive is visiopoetically meaningful to those who appreciate visual poetry, this wholesale use of cursive script counts as a significant evolution of style.

(2) My use of cursive is more elegant here than it is in mt other two recent poems making extensive use of cursive. Note, for instance, the large O, and the increased gracefulness of all the letters compared with the letters in my other two cursive poems.

(3) Twenty years ago, I didn’t bother giving my poems backgrounds. Since then I have, and have slowly been improving (but have plenty of room for further improvement). Note the harmony of the background’s shape and colors with the text, especially the O.

(4) The background has another important value–the connotations it picks up as a result of its being a variation (mostly through color changes) of the background in another poem of mine. Connecting poems of mine with others’ poems and others of my own poems is another way I’ve evolved as an artist, not doing it until perhaps twenty years ago, then only very slowly doing it to a greater and greater extent. This poem may be the first to re-use an entire background from another poem. This is not trivial, for it allows this poem to suggest “dictionary-as-temple,” the main part of the foreburden of the poem its background is from. It also should make this poem easier to enjoy, the same way the repetition in a new musical work of an old theme is usually pleasant to hear. I believe the happiness of the colors of this version of the background gains from the reminder of the different, lower-key mood evoked by the other version.

(5) The use of color in tension with greyscale is another trick new to me twenty years ago that I exploit more and more in my present works, as here (though I’ve done more with it elsewhere).

(6) I think my language has evolved over the years, too–from fairly literal to metaphorical and/or surreal. The “logic” of this piece and most of my recent pieces is not so easy to guess, which may be an unfortunate evolution, but an evolution nonetheless.

(7) You can’t tell from this image, which has been reduced in size to fit the normal computer screen, but the hard copy is larger than anything I did ten or more years ago, which is another result of evolution.

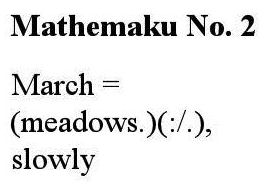

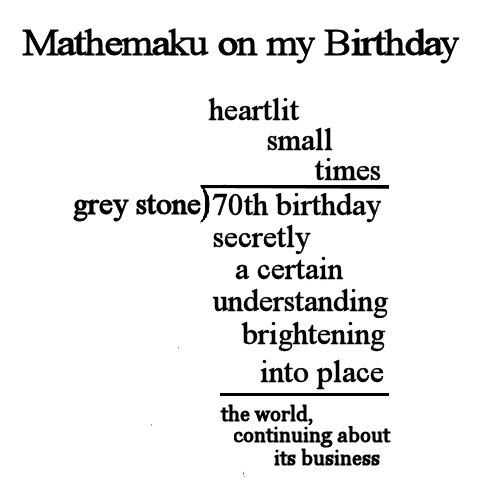

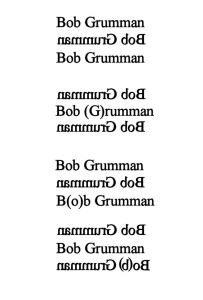

Here’s my first or second mathemaku, done thirty or more years ago, to make the profound evolution of my style more inescapable. Yet I maintain this piece is at the level of later pieces; it is simply more condensed. For one thing, it is only linguistic and mathematical. Nothing visioaesthetic happens in it. The eye is used only to recognize the symbols it contains, not to enjoy colors or shapes the way my faereality poem compels it to–i.e., not a visual poem (except inthe mindlessnesses of those for whom just about everything is a visual poem). It is short, and printed. Its words are simple to an extreme.

.

The unusual use of the punctuation marks (it was even more unusual at the time of the conception of the poem), the unusual emphasis on them (I read them, they’re meaningful, and I also see them: small plants, leaves of grass in the state of potentiality) has a strong “visioaesthetic” effect as well. There’s a playful and liric tension between the shorthand formula, and the suspense in slowing down the reading. It is still one of my favorites and I’m proud it has a Hungarian “translation”.

Ha, the fact that it was translated into nothing but symbols indicates it was not visual. I think subjective visual interpretations of symbols nice, but not enough, by themselves, to make a poem visual. Otherwise, Frost’s “Stopping by woods” is a visual poem because the o’s look like snowflakes.

Hey, gotta defend my taxonomy to the very end.

No problem. (I tried to italize the “o” but couldn’t.)

I mean: italicize. The joke is the same.