Archive for the ‘History’ Category

Entry 1028 — Halaf Culture

Thursday, February 28th, 2013

Halaf Culture

In about 6000 B.C. the Hassuna culture in northern Mesopotamia was replaced by the Halaf culture. Its origins are uncertain, but it seems to have developed in the same area as the Hassuna culture. The Halaf culture survived some 600 years and spread out to over all of present-day northern Iraq and Syria, exerting an influence that reached as far as the Mediterranean coast and the highlands of the central Zagros. In some ways, however, it was outside the mainstream of development.

The plants grown were the same as in the preceding Hassuna and Samarra periods: einkorn, emmer and hexaploid wheat, two-row hulled and six-row naked and hulled barley, lentils, bitter vetch, chickpeas and flax. The distribution of Halaf settlements lay within the

area of dry farming so that most of the agriculture was probably

carried out without the aid of large-scale irrigation. Domestic animals included the typical five species-sheep, goats, cattle, pigs and dogs-but also wild animals were hunted.

During the Halaf period people abandoned the rectangular many-roomed houses in favor of a return to round huts, called tholoi. These varied in size from about 3 to 7 meters in diameter and are believed to have housed families of one set of parents and their children. The entrance was through a gap in the outer wall, but the design varied. Often a rectangular annex was added to the circular structure. At Arpachiyeh, round buildings with long annexes formed keyhole-shaped structures almost 20 meters long with stone walls over 1.5 meters thick.

Originally the Arpachiyeh buildings were believed to be special and used for some religious ritual. However, excavations at Yarim Tepe II have suggested that most of the tholoi were used as domestic dwellings, as the rectangular chambers were entered from the circular room and did not serve as an entrance passageway as in an igloo. The tholoi were made of mud, mud-brick or stone and possibly had a domed roof. However, those at Yarim Tepe II had walls that were only 25 centimeters thick and may have been roofed using timber beams.

Tholoi have been found throughout the range of the Halaf culture, from the upper Euphrates near Carchemish to the Hamrin basin on the Iraq-Iran border. As well as having circular dwelling houses, however, the earliest and latest Halaf levels at Arpachiyeh included rectangular architecture. One such building at the latest level had been burned, with its contents left in situ. On the floor were numerous pottery vessels, many of them beautifully decorated. There were also stone vessels, jewelry, figurines and amulets as well as thousands of flint and obsidian tools. Much of the pottery and jewelry lay beside the walls, on top of charred wood that had probably been shelves. The building was at first thought to be a potter’s workshop, but that did not explain the presence of all the precious materials. It might have been a storeroom for the community’s wealth or the treasury of a local chief. In any event, there was a remarkable concentration of wealth in this one building. Yarim Tepe also had some rectangular buildings, some of which were storerooms or houses while others, which had no distinctive plan and contained no domestic debris, had possibly been public buildings.

* * * * *

I suspect some of you will be wondering why I posted the above. One reason for it is my standard quickness to post anything that’s easy to post. But I also posted it because, as I was reading it (on pages 48 and 49 of Michaell Roaf’s Cultural Atlas of Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near East), I was filled with near-religious combination of awe and pleasure–just like when connecting to one of Marton Koppany’s poems, in fact!!! I thought it an excellent example of the value of what I call informrature, and the fact that is is not necessarily inferior to poetry, just different. Although, yes, the best poetry takes much more skill to create than the informrature I quote here, which is only journalism. Informrature at the level of The Origin of Species can produce as much pleasure as the best poetry, though. More exactly, I would claim that Darwin’s book caused its earliest prepared readers to enjoy it as much as Wordsworth’s The Prelude caused its earliest prepared readers.

That “prepared” is essential to the truth of what I am saying: I got what I did from the passage from the atlas because it read it during a peculiar moment of High Preparation (slightly helped by a caffeine pill I’d taken ten or fifteen minutes earlier because I felt so sleepy too many hours before bedtime). The High Preparation was caused by many different things. One of them was my having read 47 pages about Mesopotamia, and looked at the many neato photographs and drawings on them. Another was all that I’ve read about ancient civilizations. I was simply ready to feel the size and grandeur of the time and geography as both a moment and a period that I was reading about fusedly. Okay, let me try to express it more calmly. I suddenly felt the absolute banality of what I was reading about: the list of foodstuffs; the goats, sheep, etc; the ordinary families in ordinary dwellings; the trinkets, pottery, figurines, etc., all in a little piece of land, really, in a little almost static piece of time.

I absolutely believe in, and almost worship, Cultural Progress, and here, after reading of previous Near Eastern cultures to come upon one I’d never heard of, which was almost certainly very minor, but a tributary, thrilled me.

I think, too, I’m a bit burned out as an artist and verosopher. After my reading in the atlas, my mind drifted into a daydream of taking a year off from all mental endeavors and just reading books like it. I can’t. But maybe a compromise is possible. I’ll probably have to keep a good supply of caffeine pills on hand. I have to keep telling myself there’s nothing wrong with countering an obviously endocrinological deficiency with them, the way I take thyroid pills to aid my deficient thyroid gland.

.

Great news, Bob!

I wish you quick recovery,

Marton

Bob,

Welcome back to the world of communication. Good lick recuperating.

Geof

B O L & Healing ! ! !

Thanks, all. Dunno how back to communicating I am–not up to saying much yet. But I do think I’m getting better.

Bob

Bob,

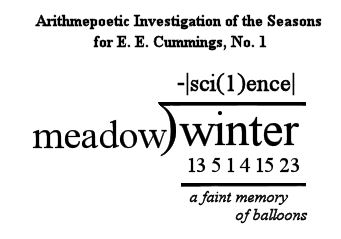

Sorry you had to go through this, but glad you’re on the other side of it now and recuperating. Like where the new mathmaku was going at latest posting. Get well. You’re due on the track.

Jake

now

when you go through an

airporte

check-point

will all of the alarms go off

and they’ll pull u out of the line

and make you dropyourpants

to show your scar ?

well be

just crwl under a bush

lich your wound

cat-like

and re:cover

Gee, thanks for giving me something to look forward to when I next travel by plane, Ed!