Archive for the ‘visual poetry’ Category

Entry 420 — Clark Lunberry’s Latest Installation

Tuesday, April 12th, 2011

.

.

.

.

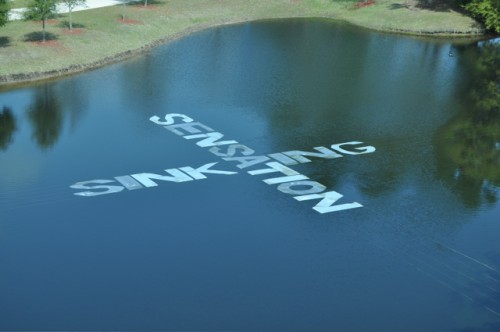

I may have it wrong, but I believe the college pond part of Clark’s installation began with the top image, then changed to “INKING/SENSATION” which, in turn, became the second image, finally becoming “SENSATION” by itself, then the bottom image, thereafter losing verbal meaning gradually until wholly gone. When I visited it, I saw the middle image. My memory is lousy but I remember it as the green of the bottom image. In any case, it was colored.

I will leave it here for now as an object of meditation as you might have happened on it walking to a class or the library of the college Clark teaches at. More tomorrow.

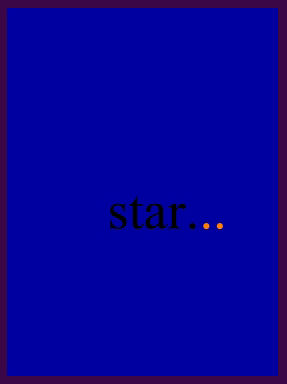

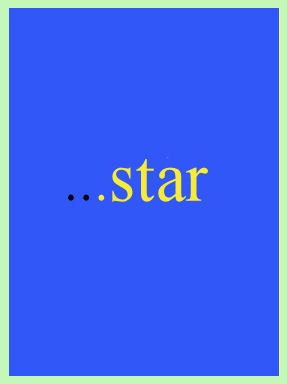

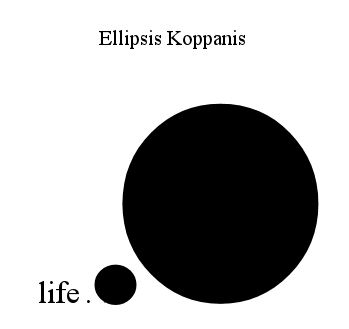

Entry 402 — Three Ellipses

Thursday, March 10th, 2011

These are all from my previous blog. The top one is “Ellipsis No. 10,” by Marton Koppany. The second is my variation on that, and the third a second variation on it by me. There here partly because, again, I could not come up with anything else to post, and partly because today I finished buying bus tickets to and from Jacksonville, Florida, where I’ll be visiting with Marton Saturday, 2 April. Anyone who’ll also be there then, let me know. Especially if you have a bed I can sleep in on Friday!

.

.

.

.

.

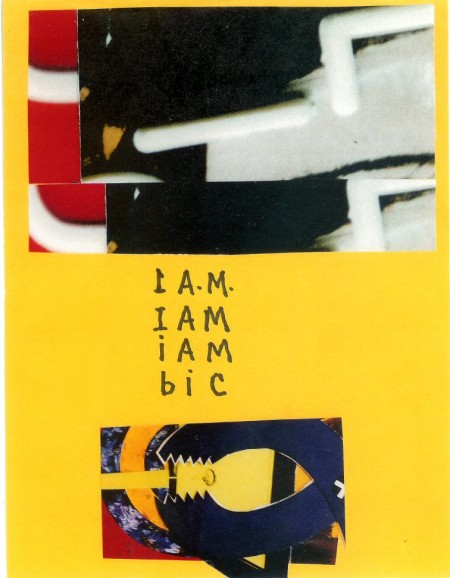

Entry 396 — A Visual Haiku

Friday, March 4th, 2011

I’m still pretty much too out of it to do a real blog entry, so here’s this from the 15 February 2009 entry to my previous blog:

.

I did a series of 5/7/5 images inspired by Scott Helmes’s slightly different visual haiku. This one I like enough to send with two or three variations on it to Jeff Hansen, who is editing a selection of poetry for Mad Hatters’ Review.

.

Entry 395 — “An Alphabet for Aram Saroyan”

Thursday, March 3rd, 2011

Entry 394 — Yesterday’s Diptych

Wednesday, March 2nd, 2011

Shortly after putting together yesterday’s entry (two days ago), I did a little work on the second of the two poems that entry featured (as I then had them). I was only going to change the quotient. I changed my mind about that, but made what I thought a terrific improvement to the sub-dividend product. With my mind on text coming out of a frame, I saw how in the first poem, I could get “understorm.” I liked that, so I changed the frame of the other poem, thus completing (I’m pretty sure) the two poems three years after throwing them together, and marveling at my ability still to be able to find little changes to make that are (for me) devastating! I’m pleased, too, with my finding new uses for old tricks, like what I do with Aram Saroyan’s “gh.”

I’m naming the poems, “Diptych in Praise of Western Civilization.” At least for now.

I hope to add more colors to these eventually.

Enter 391 — Visual Poem from March 2008

Sunday, February 27th, 2011

Entry 388 — Visual Poem, 10 February 2007

Thursday, February 24th, 2011

Entry 376 — An Ultimate Definition of Poetry

Saturday, February 12th, 2011

.

First, to get my latest coinage out of the way before I forget it: “urentity.” I’m not keen on it but need something for more or less fundamental things like photons and electrons–both larger like atoms, and smaller like quarks; for light, too, and maybe gravity. There may be good term for this already out there; if so, I’m not aware of one, and I’ve often wanted one. “Bit of matter” would be good enough if there weren’t some things not considered material, like light.

Maybe “fundent.” “Urentity” is pissy my ear now tells me.

What follows are notes written yesterday toward a discussion of how to define poetry.

Last night I felt I was putting together a terrific monograph on the subject but now, around 3 in the afternoon, I’ve found I haven’t gotten anywhere much, and am out of gas, so will add a few thoughts to what I’ve said so far, without keeping it very well organized.

The best simple definition of poetry has for thousands of years been “literary artworks whose words are employed for substantially more than their ability to denote.” With “literary artworks” being defined as having to have words making some kind of sense whose purpose is to provide aesthetic pleasure to a greater degree than indoctrination or information, the other two things words can provide.

A more sophisticated definition would list in detail exactly what beyond denotation poetry’s words are employed for, mainly kinds of melodation (or word-music), figurative heightening, linguistic heightening (by means of fresh language, for instance) and connotation. Arguments have always risen about what details a poem should have to qualify as a poem–end-alliteration, the right number of syllables, meter, end-rhyme, etc., with philogushers almost always sowing confusion by requiring subjective characteristics such as beauty, high moral content, or whatever.

Propagandists work to make salient words ambiguous. They never provide objective, coherent definitions of their terms. Diana Price, the anti-Shakespearean, for instance, attacks the belief that Shakespeare wrote the works attributed to him but saying there’s no contemporary personal literary evidence for him, but in her few attempts to define what she means in her book against Shakespeare does so partially, and inconsistently. I bring this up because I hope someday to use her book in a book of my own on the nature and function of propaganda.

I’m not bothering with that right now. I’m intent only on establishing that poetry has always been, basically, heightened language used to entertain in some way and/or another, with different poetic devices being required by poets of different schools of the art. At present a main controversy (although now over a century old) is whether verbal texts using only the device of lineation (or the equivalent) can qualify as poetry, but it would appear that for the great majority of poets and critics, the answer is yes. The most recent controversy has to do with whether poetry making in which non-verbal elements are as important as verbal elements can be considered poetry. the outcome is uncertain but it would seem that another yes will result. Amazingly enough–to me, at any rate–is the belief of many visual artists who make letters and other linguistic symbols the subject of painting that such . . . “textual designs,” I call them . . . are poetry, “visual poetry.” The question has not reached enough people in poetry to be considered controversial yet, I don’t believe–however controversial in my circles.

My newest and best definition of visual poetry is: “poetry (therefore verbal) containing visual elements whose contribution to its central aesthetic effect is more or less equally to the contribution to that of the poem’s words.”

It is constantly claimed how blurry and ever-changing language is, but I’m not sure it is. It seems to me that most of our language is quite stable, and that only language about ideas, which are forever changing, is to any great extent capricious. Sure, lots of terms come and go, but only because what they describe comes and goes. “Poetry,” was reasonably set for millennia, and uncertain only now because for the first time a significant number of artists are fusing arts, thus requiring new terms like “visual poetry,” and amendments to definitions like “poetry.”

A precise, widely agreed-on definition of “poetry” is essential not only for critics but for poets themselves, no mater how little many of them realize it. They want to use it freely, and should if you believe with me that “poetry is the appropriate misuse of language.” A metaphor is a misuse of language, a lie. Calling me a tiger when it comes to defending the rational use of language is an example. I’m not a tiger. But I act in some ways like a tiger. A metaphor actually could be considered an ellipsis–words left out because understood, in this case saying “Bob is a tiger” rather than “Bob is like a tiger.” In any case, if we don’t accept the definition of tiger as a big dangerous cat, the metaphor will not work.

To say a word can have many meanings according to its context does not make it polysemous, although if provides the word with connotational potential the poet can take advantage of.

James Joyce’s “cropse’ is a neat misspelling but useless if one does not accept the precise meanings of “crops” and “corpse.”

Entry 360 — Thoughts about Definitions

Thursday, January 27th, 2011

Mathematical Poetry is poetry in which a mathematical operation performed on non-mathematical terms contributes significantly to the poem’s aesthetic effect.

Mathematics Poetry is poetry about mathematics.

Neither is a form of visual poetry unless a portion of it is significantly (and directly) visio-aesthetic.

The taxonomic rationale for this is that it allows poetry to be divided into linguexclusive and pluraesthetic poetry–two kinds based on something very clear, whether or not they make aesthetically significant use of more than one expressive modality, with the second category dividing cleanly into poetries whose definition is based on what extra expressive modality they employ–visual poetry, for example, employing visimagery; mathematical poetry employing mathematics; and so forth.

Directly. I mentioned that because there are some who would claim that a linguexclusive poem about a tree so compellingly written as to make almost anyone reading it visualize the tree is a “visual poem.” But it sends one to one’s visual brain indirectly. A genuine visual poem about a tree, by my definition, would use a visual arrangement of letters to suggest a tree, or graphics or the like directly to send one to one’s visual brain.

A confession. I’ve been using the pwoermd, “cropse,” as an example of a linguexlusive poem that muse be seen to be appreciated, but is not a visual poem. Yet it is almost a visual poem, for it visually enacts the combination of “corpse” and “crops” that carries out it aesthetic purpose. To call it a visual poem, however, would ignore its much more potent conceptual effect. I claim that it would be experienced primarily in one’s purely verbal brain, and very likely not at all in one’s visual brain. One understands its poetry as a conception not as a visimage. When I engage it, I, at any rate, do not picture a corpse and crops, I wonder into the idea of the eternal life/death that Nature, that existence, is. It is too much more conceptual than visual to be called a visual poem.

I had a related problem with classifying cryptographic poetry. At first, I found it clearly a form of infraverbal poetry–poetry depending for its aesthetic effect of what its infraverbal elements, its textemes, do, not on what its words and combinations of words do. It was thus linguexclusive. But I later suddenly saw cryptography as a significant distinct modality of expression, which would make cryptographic poetry a kind of pluraesthetic poetry. Currently, I opt for its being linguexclusive, for being more verbo-conceptual than multiply-expressed. A subjective choice. Taxonomy is difficult.

For completeness’s sake, a comment now that I made in response to some comments made to an entry at Kaz’s blog about my taxonomy: “Visual poetry and conventional poetry are visual but only visual poetry is visioaesthetic. The point of calling it ‘visual’ is to emphasize the importance of something visual in it. In my opinion, the shapes of conventional poems, calligraphy, and the like are not important enough to make those poems ‘visual.’ Moreover, to use the term ‘visual poem’ for every kind of poem (and many non-poems) would leave a need for a new term for poems that use graphics to their fullest. It would also make the term of almost no communicative value. By Geof’s logic we would have to consider a waterfall a visual poem because of its ‘poetry.’ Why not simply reduce our language to the word, ‘it?’”

Entry 297 — Beining III

Saturday, November 27th, 2010

.

This is my favorite of Guy’s three. I didn’t get the game the text plays right off. Even without it, the piece is major–one of those works that make me think I’m in some non-human species so little do I understand why so much trash wins adulation and works like this hang nowhere but in galleries like this, at best.

![DSC_1536[12]](/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/DSC_153612-e1302650888895.jpg)