Archive for the ‘Miscellaneous Literary Thoughts’ Category

Entry 1517 — Interruptions

Thursday, July 24th, 2014

I’m interrupting my reading of an essay by Jan Baetens about minimalist poetry to say that it just made me see that there are two kinds of minimalist poetry: poetry whose form is minimal in size, and poetry whose content is minimal in size. The letter “a” repeated 1776 times in a font a foot high would be an example of the latter, the kind of poems I’ve always thought of as the only kind of minimalist poem–“lighght,” for instance–are the other kind. Then there are poems like “tundra,” which takes up a whole page (and at its best should probably take up a page ten feet wide), so is larger than many conventional poems, but whose content is not minimal in size, or John M. Bennett’s “The Shirt, The Sheet.” which is a sound poem consisting of those four words repeated indefinitely, so with an unminimal form but with variations that make its content nowhere near minimal in content.

Conclusion: I must define a minimalist poem as one whose content approaches zero and/or whose form does.

Meanwhile, I suddenly want to write an essay on the innate morality I believe we all have. I hope to have it here tomorrow. Then, maybe, I will return to what I may be calling “The Poetry Enterprise in America.”

.

Entry 1239 — The Dwindle Continues

Thursday, October 10th, 2013

As I continue this blog, I try to think why. All I can come up with is that maybe it will be a useful record of the dwindle of a mind once not-so-bad. Anyway, I do have some more SASEs, I’m pretty sure but I thought I’d take care of this entry with something I said two days ago instead:

Comment to Richard Kostelanetz When He Disagreed With Me That Rating a Poet’s Inventiveness Would Be Difficult

Well, I guess it’s all in how one defines “poetic inventiveness.” I should think it difficult to rate one invention against another, too. And, of course, how to determine who invented what. I think I could claim up to a thousand inventions–but there isn’t one of them that I’m sure is my invention. How about Gertrude? Two inventions–ignoring grammar and hyper-repetition? Or was each of her tender buttons an invention? If the latter, is it possible each of her buttons contained two or more inventions?

.

Entry 1204 — The Exerioddicist, July 1993, P.1

Thursday, September 5th, 2013

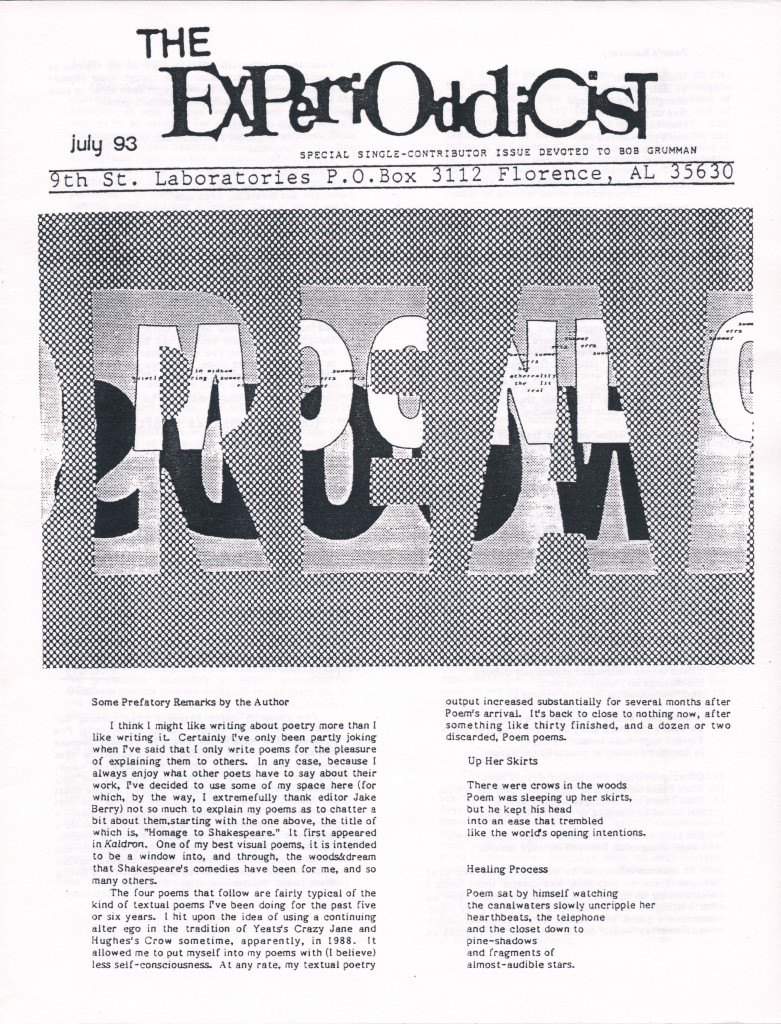

While looking for a poem for use in my Scientific American blog, I came across the following, an issue of Jake Berry’s 4-page The Experioddicist from July 1993 that was entirely devoted to Me:

I think it pretty danged fine, and not entirely self-centered, for it has criticism of material by others. I hope that by holding down the control button and clicking the + button, you can get an enlargement you can read. My next three blog entries will have the other three pages–and give me extra time to work on other things.

.

Entry 1087 — P&B, Series . . . Call It 5

Sunday, April 28th, 2013

P&B is short for “pronouncements and blither.”

At some point in a long Internet discussion with Richard Kostelanetz about the Establishment, I remarked that, “Academic and commercial presses ARE the establishment, or essentially if many time implicitly told what to publish by it. Actually, on reflection (gee, I had that word ready to use then lost it for a full two minutes, except for the “re”), I see that it might make sense to divide the Establishment in two, although they overlap: the academic/commercial establishment that rules contemporary literature, and the one that rules the art of the past. You’ve built your reputation, it seems to me, in the latter (which is where academia is at its best, and often splendid), but not so much in the former–not because of lack of support but because the morons in charge of the former are thirty to fifty years behind what’s going on where most of the best art is coming into existence.

In another discussion, this one at New-Poetry, with a number of participants, Sam Gwynn disagreed with me that “if a poet wants maximal musicality, formal poetry is for him,” with the claim that Whitman achieved maximal musicality in his free verse.

You know, Sam, after really really thinking this over, which is uncharacteristic of me, I concluded that I disagree. It seems to me that if I were a composer, and wanted to achieve maximal musical beauty, I would write for a symphony orchestra, not a quartet–or for a piano, not a flute. Someone will throw Beethoven’s quartets at me, or some glorious melody for a flute, but my point is that a formal poet has all possible auditory devices know to poetry (I think) to work with, a free verser doesn’t. A free verser, or composer for quartet or flute, may still achieve things some subjectively find better than anything else (Hey, I think Thomas Wolfe was wonderfully musical–although that was when I was under 25), but what can he do to achieve what, say, Frost does with rhyme in his Snowy Evening poem? I suppose it’s subjective, although I believe it will not too long from now be objectively provable by comparing what happens in the brain listening to Whitman versus listen to Frost, that nothing in poetry can surpass the music of Frost’s rhymes. I further claim they do what chords do in real music, a rhyme causes you to hear two related notes together in a way nothing else does–and in Frost’s poem, you get THREE together.

Did I show that in my knowlecular poetics discussion of the rhyme? I can’t recall. . . .

Okay, maybe my gush above is due my bias in favor of Frost, who seems to me to do just about everything word-only poets do better than Whitman, however admirable in so many ways that Whitman may be.

I note now that I’ve quoted myself, that I forgot that, for me, Whitman is a formal poet, albeit a borderline one, due to his use of Psalmic parallelism.

.

Entry 1049 — Back to the Nuthouse Fellow

Thursday, March 21st, 2013

I stole the material below fromThe Public Domain Review

Bacon goes on to explain that the man, after leaving the asylum, went “to work at his trade, and, by steady application, succeeded in arriving at a certain degree of prosperity, but some two or three years later he began to write very strangely again, and had some of his odd productions printed ; yet all this time he kept at work, earned plenty of money, conducted his business very sensibly, and would converse reasonably.”

After a visit from a medical man who tried to dissuade him from writing this way the man wrote the following letter:

Dear Doctor, To write or not to write, that is the question. Whether tis nobler in the mind to follow the visit of the great ‘Fulbourn’ with ‘chronic melancholy’ expressions of regret (withheld when he was here) that, as the Fates would have it, we were so little prepared to receive him, and to evince my humble desire to do honour to his visit. My Fulbourn star, but an instant seen, like a meteor’s flash, a blank when gone. The dust of ages covering my little sanctum parlour room, the available drapery to greet the Doctor, stowed away through the midst of the regenerating (water and scrubbing – cleanliness next to godliness, political and spiritual) cleansing of a little world. The Great Physician walked, bedimmed by the ‘dark ages’ the long passage of Western Enterprise, leading to the curvatures of rising Eastern morn. The rounded configuration of Lunar (tics) garden’s lives an o’ershadowment on Britannia’s vortex…

Unfortunately things ended sadly for the man. As Bacon recounts: “In the course of another year he had some domestic troubles, which upset him a good deal, and he ended by drowning himself one day in a public spot”.

(Images taken from On the Writing of the Insane (1870), housed at the Internet Archive, contributed by the Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine via the Medical Heritage Library. Hat-tip to Pinterest user Marisela Norte).

* * *

A hat-tip from me to Karl Kempton, too, for discovering this site and directing me to it.

* * *

I thought I’d add a few thoughts–

———–Hey, remember me quest to find 26 words, each with a different silenced letter of the alphabet? “Thought” reminds me that I found “although” wherein the u is silent. Before that I thought of “squire,” then disqualified it on the grounds that its u partakes of the pronunciation of its q. As I wrote that, I thought of quixote as a word in which an x is silent, but am not quite willing to accept it because it’s a name. It does suggest that there must be more normal words from Spanish in our language in which an x is silent.

Back to my thoughts on the asylum patient’s works. They seem to me special instances of shaped poems, or not really very poetic because essentially decorative arrangements of informrature. That tends to be my problem with the many Christian arrangements of Jesus’s name or religious texts from medieval times. Even if we take the asylum patient’s work as visual poetry, I would not call him a precursor of Modern Visual Poetry. The most important reason I would not is that he influenced no one that we know of in modern visual poetry. I hold that an artist must not only make major art to be major, but influence others. He must have not only a talent for art, but a talent for making that art sufficiently a part of the culture of to influence other artists. Eventually influence them, as Dickinson did, with a minimal talent for making her art part of the culture of her times, but enough to get just enough of it known–particularly to Higginson (if, going from memory, I have his name right), her one influential friend–to make it available to influence other poets after her death.

I don’t think the mental patient has influenced anyone even though others have done works like his because they made their works without knowing his, nor knowing works like his by people influenced by him.

Similarly, it’s questionable that Lewis Carroll’s visual poetry influenced any serious poet. The first full-scale modern visual poet in my view (so far as I know) was Apollinaire, and I don’t think he was aware of Carroll’s work. I deem Apollinaire full-scale, Mallarme not, by the way, because I (quite subjectively) consider Mallarme using words in a visually connotative but not really metaphorical way, whereas Apollinaire took a partial step from visual connotative use of words to metaphorical use of them. I think I’m saying Mallarme was visieopoetically suggestive, Apollinaire visiopoetically explicit.

To create a visual sprawl around what I’m trying to say in hopes it will be enough to help me (or someone using what I’ve said here) to improved expression. . . .

.

Entry 1032 — Paraphrasing, Etc.

Monday, March 4th, 2013

Entry 979 — A New Poetry Submission Procedure

Wednesday, January 9th, 2013

I was reading about an editor of Poetry who was talking about how many poems he has to read each year–something like 30,000, if I remember rightly. It struck me that it would be impossible for him to choose the best from so many, even if he didn’t quickly recognize most otherstream poems without reading them and automatically reject them. Thinking further about it, I came up with an idea I think quite brilliant, albeit 100% unfeasible. Require each person submitting a poem to include with it his answers to the following questions: “what, if anything, is in your poem that is in extremely few other poems, and why is it of value?” and “what are you doing in your poem that many poets are also doing but which you are doing better than just about any of them, and why is it of value?”

Actually, that wouldn’t save the editor much time since he’d just be trading poem-reading time for answer-reading time. But it might reduce the number of poets submitting since it might force at least some of them to recognize that their poems neither have anything valuably new in them or do anything of value better than almost any other poet. And some of those who have no idea what they’re doing as poets would be intimidated sufficiently by the questions not to submit.

Maybe the submitter could be required to provide evidence of whatever claim he was making–a sample of what made his poem superiorly conventional or new.

Just thoughts.

I don’t think there are too many people composing poems, by the way–just too many mediocrities publishing them. What would be really nice would be only a dozen or so publications devoted to poetry, all of them edited by genuine experts in poetry. But leave the Internet open to all comers in the field.

As I was thinking about all this, I wondered about making a computer program for sifting mediocre and sub-mediocre poems from poems with a chance of being good. I believe an effective program that could do this is possible. I’d flow-chart it myself if financed. It’d be pretty interesting even if never used. It wouldn’t be easy to make. One would have to find ways the computer could recognize various components of any poem. I wonder if spell-checkers could provide a basis, at least in part, for such a program. They are ridiculously poor at times, but actually quite sophisticated, and improving all the time, I’m sure. Again call I for a Patron! Wherefore are the ears of the Cultured Rich as stone unto mine pleas?

.

Entry 900 — The Anthology from Fantagraphics

Tuesday, October 23rd, 2012

I got my contributor’s copy of this yesterday. I don’t love every work in it but I think there are almost no works in it that I’d call poor, and many that I think terrific. My highest rating is always for works I want to steal from, or steal completely, and I’ve already come across more than ten of these, in just a few fast skims. My favorite so far in one by Kathy Ernst, “Viole(n)t,” which is . . I was just about to say unstealable because anything you could use it or a part of it in would look stupit compared with it. Then I thought of one way you could steal from it, or from any work: steal just a detail, or–better–a fraction of a detail, just enough so a viewer knowing Kathy’s work wiykd recognize it; this way you could use it as an allusion that might make everything near it seem minor, but not the whole work it was in due to how small it was. Hey, I think I could make it work!

Note: I think every good poem has stolen elements in it. It may be the the more stolen elements it has, the better it is. No, make that the best poems have the most stolen elements, but some bad poems have a lot of stolen elements, too.

.

Entry 872 — Making a List of Literary “Bests”

Tuesday, September 25th, 2012

Marcus Bales’s facebook page has a link to a silly list of the 20th-century’s best works of fiction in English. The Great Gatsby came in first, I believe–or else very high up. It isn’t even Fitzgerald’s best work–Tender is the Night is. I like This Side of Paradise better than Gatsby, too, although or because it’s so obviously a not-yet fully-adult writer’s work. I liked many of his short stories, too- the ones most critics consider commercial fluff. I don’t know novels well enough to be sure, but I don’t think I’d put any of his in the top fifty anglophonic novels of the last century. But even The Great Gatsby is superior to most of the other novels on the list.T

It was a consensus of four lists of “experts.” It got me thinking about some better way of ranking works: prepare a detailed test of works in English of the time and give it to anyone who wants to contribute to the list. Then ask each of them for 5,000 words on the kind of work to be listed. Give each person all the papers resulting, asking each to rank them in reverse order. Find each person’s average score. Multiply each score a given person gives to a work by the average score his paper receives. Add up the scores. The one with the highest total points is number one. A little complicated, but the list resulting would be ten times better than the one Fitzgerald’s novel was first on. The point is simple: ratings by intelligent knowledgeable people should count more than ratings by dolts.

A better way I think I’ve already discussed here: work out a formula for an effective novel and program a computer to use it on all the works to be ranked. Test it on a hundred works just about everyone considers great, and a hundred just about everyone thinks terrible. Eventually, one could have many programs ranking works, each based on a different critic’s criteria. Then maybe a moron-vote to determine to rank the lists. Or my previous method. Probably by the time anything a computer could do to get a reasonable list, a computer could give a true evaluation of a person’s over-all intelligence, and literary intelligence, if that were indeed a different sort of intelligence, which I tend to doubt. Visimagistic and musical intelligence, I’m sure, would be. Then a list could be compiled based on the evaluations of the hundred scoring the highest in literary intelligence, with penalites for not having read any work among the contestants.

Saying that makes me realize that a big problem with these lists is that, so far as I know, works left off a given lister’s list because he’s not familiar with it count against the work. Any evaluation should be of the works on a huge list, and those works only, with some way of making up for works not known to many. The problem is that they may not be known to many because they’re no good, so, you can’t just go by the average score each work gets. Maybe have one give the mean score to each work he’s unfamiliar with–if rating 999 books, that would be 500. Or try something else. I’m more indicating something to be worked out than giving anything like a final solution.

Then there is my ongoing problem with ranking artworks, one that apparently on one else has: factoring in the difference between a work’s direct value to the general public, and the work’s direct value to the art. The Great Gatsby will score much more than Finnegans Wake in direct value to the public, but much less than Finnegans Wake to the art. As I’ve said before, I would opt for two separate lists, one for the most effective books, and one for the most important books.

Another problem is which should count more, individual works, or oeuvres. I suppose that could be taken care of simply by having lists for each. As I’ve also said before, Stevens would finish first for pre-1960 poets in English on the effective oeuvre list but I’m not sure what poem would. “Tintern Abbey” would be a contender as would “Stopping by Woods.” Nothing by Stevens, I don’t think, though several of his in the top hundred. Cummings would be first on my list of most important poets in English, and his oeuvre wouldn’t do badly on the most effective oeuvre list, but he’d only have only two or three high-ranking poems on the effective list. On the other hand, maybe his “in just-spring” would compete for first there. I guess it would depend on my mood where I placed it. Choosing poems would be incredibly hard–there wouldn’t be that much difference between the most effective, and the thousandth most effective. I’m not sure there’d be as many as a hundred poems eligible for a list of the most important poems. Even Ginsberg’s “Howl” would have to be on it. Half the poems on it would be by Cummings.

Urp.

.

Entry 788 — Poets & Writers Questionnaire

Tuesday, July 3rd, 2012

Here it is:

1. Yes, I am interested in participating in either a phone interview (30 minutes) or focus group (90 minutes) or both

2. Please tell us what you write. Poetry, Fiction

3. Do you write genre fiction? Yes

4. If you write genre fiction, please indicate which type. Science Fiction

5. Are you a translator? No

6. Do you write books for children?

7. Do you write books for young adults? Not yet

8. Have you published a book? Yes

9. If you’ve published one or more books, how were they published?

Both Published by a publisher and Self-published

10. Would you be willing to participate in a focus group in Manhattan? Could not afford to

11. Would you be willing to participate in a focus group in downtown Los Angeles.? Could not afford to

12. Do you use Google+ Hangouts? No (Don’t know what these are.)

13. Would you be willing to participate in a virtual focus group using Google+ Hangouts? Don’t know what it is.

14. On weekdays, what time of day would be best for you to participate in a focus group? Any time

15. Do you subscribe to Poets & Writers Magazine? No

16. Do you subscribe to our e-newsletter? No

17. Have you received payment from Poets & Writers for a reading you’ve given or a workshop you’ve conducted? That’s a laugh.

18. Are you listed in our Directory of Poets & Writers? Yes

19. Do you participate in our online Speakeasy? No

20. Your age? Over 65

21. Your ethnic background? White, not Hispanic

22. Your gender? Male

23. Please provide your name, email address and information on where you live. Provided

I find nothing in it to indicate Poets & Writers has a genuine interest in finding out what it can do to help poets and writers. They should, at the very least, have someone answering their questionnaire tell how he rates their magazine from 1 for I think it very bad to 5 for I think it very good, to be sure of getting a few people who could actually help them do what they say they want to do. They should ask for comments, too. Such as a yes/no question about whether the answerer has ever published any kind of opinion piece on the state of literature in America, with a follow-up determining how often he has, if he has. More specific question on the kind of poetry done would help–a list of the Wilshberian poetries and “other.” If I had time, I’m sure I could think of other good questions. The results of P&W’s effort to improve should be amusing.

.