Posts Tagged ‘diversity of awarenesses’

Entry 4 — The Nature of Visual Poetry, Part 2

Thursday, November 5th, 2009

Note to anyone dedicatedly trying to understand my essay, you probably should reread yesterday’s segment, for I’ve revised it. Okay, now back to:

The Nature of Visual Poetry

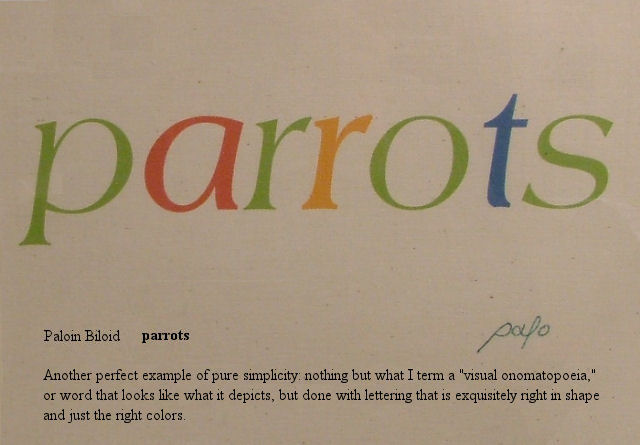

As a visual poem, Biloid’s “Parrots” is eventually processed in two significantly different major awarenesses, the protoceptual and the reducticeptual. In the protoceptual awareness, the processing occurs in the Visioceptual Awareness, to which it directly proceeds. In the reducticeptual awareness, it first goes to the Linguiceptual Awareness, which is divided into five lesser sub-awarenesses, the Lexiceptual, Texticeptual, Dicticeptual, Vocaceptual, Rhythmiceptual and Metriceptual. The first is in charge of the written word, the second of the spoken word, the third of vocalization, the fourth of the rhythm of speech and the fifth of the meter of speech. Of these, the linguiceptual awareness passes “Parrots” on only to the first, the lexiceptual awareness, because “Parrots” is written, not spoken. Since the single word that comprises its text will be recognized as a word there, it will reach its final cerebral destination, the Verbiceptual Awareness.

The engagent of “Parrots” will thus experience it as both a visioceptual and a verbiceptual knowlecule, or unit of knowledge–at about the same time. Visually and verbally, the first because it is visual, the second because it is a poem and thus necessarily verbal. Clearly, it is substantially more than a conventional poem, which would be processed entirely by its engagent’s verboceptual awareness.

Okay, this essay, only about a thousand words in length so far, is already a mess. Yes, way too many terms. And I keep needing to revise it for clarity. Or, at least, to reduce its obscurity. I have trouble following it myself. My compositional purpose right now, though, is to get everything down. Later, I’ll simplify, if I can.

Entry 2 — The Ten Knowlecular Awarenesses

Tuesday, November 3rd, 2009

Okay, today the first installment of my discussion of the nature of vispo, which begins with a summary of my theory of “awarenesses”:

A Semi-Super-Definitive Analysis of the Nature of Visual Poetry

It begins with the Protoceptual Awareness. It begins there for two reasons: (1) to get rid of the halfwits who can’t tolerate neologies and/or big words, and to ground it in Knowlecular Psychology, my neurophysiological theory of psychology (and/or epistemology). The protoceptual awareness is one of the ten awarenesses I (so far) posit the human mind to have. It is the primary (“proto”) awareness–the ancestor of the other nine awarenesses, and the one all forms of life have in some form. As, I believe, “real” theoretical psychologists would agree. Some but far from all would also agree with my belief in multiple awarenesses, although probably not with my specific choice of them. It has much in common with and was no doubt influenced by Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences.

The protoceptual awareness deals with reality in the raw: directly with what’s out there, in other words–visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory, gustatory stimuli. It also deals directly with what’s inside its possessor, muscular and hormonal states. Hence, I divide it into three sub-awarenesses, the Sensoriceptual, Viscraceptual and Musclaceptual Awarenesses. The other nine awarenesses are (2) the Behavraceptual Awareness, (3) the Evaluceptual Awareness, (4) the Cartoceptual Awareness, (5) the Anthroceptual Awareness, (6) the Sagaceptual Awareness, (7) the Objecticeptual Awareness, (8) the Reducticeptual Awareness, (9) the Scienceptual Awareness, and (10) the Compreceptual Awareness.

The Behavraceptual Awareness is concerned with telling one of one’s behavior, which this awareness (the only active awareness), causes. For instance, if someone says, “Hello,” to you, your behavraceptual awareness will likely respond by causing you to say, “Hello,” back, in the process signaling you that that is what is has done. You, no doubt, will think of the brain as yourself, but (not in my psychology but in my metaphysics) you have nothing to do with it, you merely observe what your brain chooses to do and does. But if you feel more comfortable believing that you initiate your behavior, no problem: in that case, according to my theory, your behavraceptual awareness is concerned with telling you what you’ve decided to do and done.

The Evaluceptual Awareness measures the ratio of pain to pleasure one experiences during an instacon (or “instant of consciousness) and causes one to feel one or the other, or neither, depending on the value of that ratio. In other words, it is in charge of our emotional state.

The Cartoceptual Awareness tells one where one is in space and time.

The Anthroceptual Awareness has to do with our experience of ourselves as individuals and as social beings (so is divided into two sub-awareness, the egoceptual awareness and the socioceptual awareness).

The Sagaceptual Awareness is one’s awareness of oneself as the protagonist of some narrative in which one has a goal one tries to achieve.

The Objecticeptual Awareness is the opposite of the anthroceptual awareness in that it is sensitive to objects, or the non-human.

The Reducticeptual Awareness is basically our conceptual intelligence. It reduces protoceptual data to abstract symbols like words and numbers and deals with them (and has many sub-awarenesses).

The Scienceptual Awareness deals with cause and effect, and may be the latest of our awarenesses to have evolved.

Finally, there is the Compreceptual Awareness,which is our awareness of our entire personal reality. I’m still vague about it, but tend to believe it did not precede the protoceptual awareness but later formed when some ancient life-form’s number of separate awarenesses required some general intelligence to co:ordinate their doings.

I have a busy day ahead of me, so will stop there.

Roundedness is wonderful, and fitting in is fabulous. However, genius doesn’t require either to create or postulate.

As I said, roundedness is something I need to think about more. I, of course, am not implying that genius requires it but suggesting that

the higher one’s roundedness quotient is, the more effective one will

likely be at creating or postulating–although one’s creativity quotient

would outweigh it, as would a true intelligence quotient, which would

measure much more than short-term numeracy and literacy and the mental manipulation of geometric shapes and whatever else most IQ tests measure.

This response is late, by the way, because I didn’t know I got your comment till today (due to my ignorance about how this site handles comments).

Later Note, 4 August 2011: is there anyone more stupid than the person who enters a discussion only to make an assertion (anonymously, of course), then disappears?

–Bob