Entry 436 — Visual Poetry Intro 1a

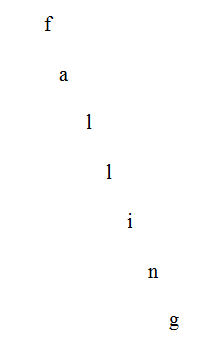

According to Billy Collins, E. E. Cummings is, in large part, responsible for the multitude of k-12 poems about leaves or snow

But, guess what, involvement in visual poetry has to begin somewhere. Beyond that, this particular somewhere, properly appreciated, is a wonderful where to begin at. Just consider what is going on when a child first encounters, or–better–makes this poem: suddenly his mindflow splits in two, one half continuing to read, the other watching what he’s reading descend. For a short while he is thus simultaneously in two parts of his brain, his reading center and visual awareness. That is, the simple falling letters have put him in the Manywhere-at-Once I claim is the most valuable thing a poem can take one to.

To a jaundiced adult who no longer remembers the thrill letters doing something visual can be, as he no longer remembers the thrill the first rhymes he heard were, that may not mean much. But to those lucky enough to have been able to use the experience as a basis for eventually appreciating adult visual poetry, it’s a different story. Some of those who haven’t may never be able to, for it would appear that some people can’t experience anything in two parts of their brains at once, just as there are people like me who lack the taste buds required to appreciate different varieties of wine. I’m sure there are others who have never enjoyed visual poetry simply because they’ve never made any effort to. It is those this essay is aimed at, with the hope it will change their minds about the art.

I need to add, I suppose, that my notion that a person encountering a successful visual poem will end up in two significantly separate portions of his brain is only my theory. It may well be that it could be tested if the scanning technology is sophisticated enough–and the technicians doing the testing know enough about visual poetry to use the right poems, and the subjects haven’t become immune to the visual effects of the poems due to having seen them too often. Certainly, eventually my theory will be testable.

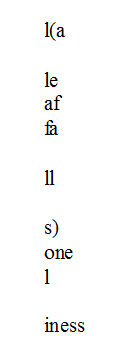

The following poem by Cummings, which is a famous variation on the falling letters device, should help them:

But Cummings uses the device much more subtly and complicatedly– one reads it slowly, back and forth as well as down, without comprehending it at once. Cummings doesn’t just show us the leaf, either, he uses it to portray loneliness. For later reading/watchings we have the fun of the three versions of one-ness at the end and the af/fa flip earlier–after the one that starts the poem.

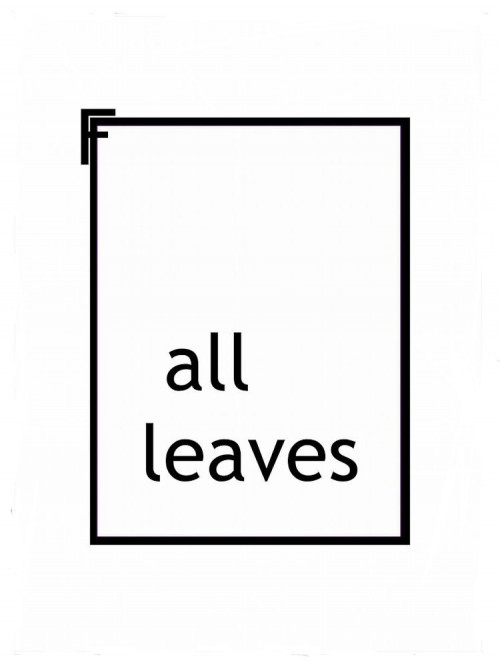

Marton Koppany returns to the same simple falling leaf idea but makes it new with:

In this poem the F suggests to me a tree thrust almost entirely out of Significant Reality, which has become “all leaves”–framed, I might add, to emphasize the point. So: as soon as we begin reading, our reading becomes a viewing of a frame followed quickly by the sight of the path now fallen leaves have taken simultaneously with our resumed reading of the text. Which ends with a wondrous conceptual indication of “the all” that those leaves archetypally are in the life of the earth, and in our own lives. And that the tree, their mother and relinquisher, has been. Finally, it is evident that we are witnessing that ” all” in the process of leaving . . . to empty the world. In short, the archetypal magnitude of one of the four seasons has been captured with almost maximal succinctness.

So endeth lesson number one in this lecture on Why Visual Poetry is a Good Thing.

Note: I need to add, I suppose, that my notion that a person encountering a successful visual poem will end up in two significantly separate portions of his brain is only my theory. It may well be that it could be tested if the brain- scanning technology is sophisticated enough–and the technicians doing the testing use the right poems, and the subjects haven’t become immune to the visual effects of the poems due to having seen them too often. Certainly, eventually my theory will be testable.

Hmmm . . . . all leaves in fall.

Was this one of the response to Dan Waber’s “Fall leaves” project?

– endwar

I’m away from the files in my main computer so can only tell you it was a response to one project of Dan’s, probably the one you mention. Not sure, though, It had to do with work by bp Nichol, though.