.

.

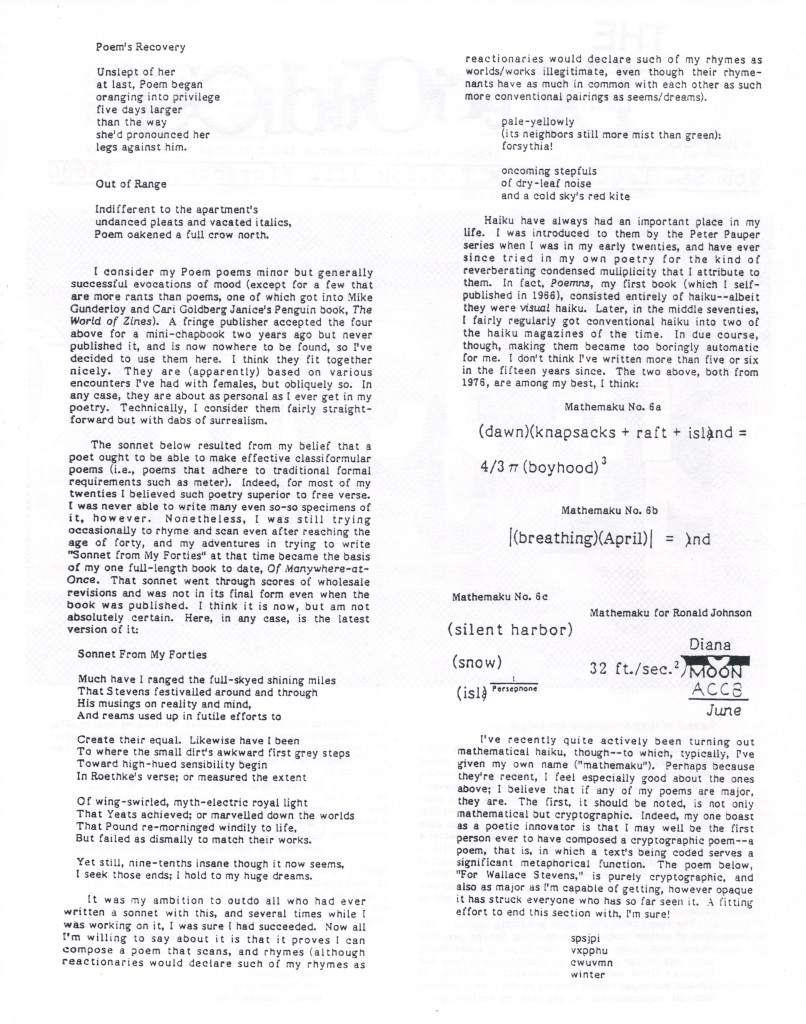

. JOE

.

.

. JOE

.

.

The poem above is by Robert Grenier. I quoted it in #661, with some words of Ron Silliman’s about it. Then in #662, I weighed in about it with much the same discussion that follows. During that discussion, I mentioned a weak parody of it by David Graham that charmed the other stasguards at New-Poetry, none of whom has much sensitivity to minimalistic poetry.

To write an effective parody, you have to understand the text, or kind of text, you are parodying, and Graham understood only the surface of this one–the fact that it consists of two words. His parody of the poem consisted of the single letter, O. It is a parody within a parody of Silliman’s text, though. This is somewhat better because he pretty much just repeats what Silliman said about “JOE,” but applied to “O.” He got one minor thing right: by raving about the O as also a zero, he indicated that he’s somehow learned that one frequently employed technique of minimalist poems is visual punning, or a text whose visual appearance can be interpreted as two different words, or the equivalent, that do not sound the same. But he didn’t demonstrate he really knew anything about minimalist poetry or about “JOE.”

Here’s what Silliman said about it: “One could hardly find, or even imagine, a simpler text, yet it undermines everything people know or, worse, have learned, about titles, repetition, rhyme, naming, immanence. If we read it as challenging the status of the title, then on a second level it is the most completely rhymed poem conceivable. & vice versa.

As language, this is actually quite beautiful in a plainspoken manner, the two words hovering without ever resolving into a static balance, never fully title & text, nor call & response, neither the hierarchy of naming nor parataxis of rhyme.”

I have a confession to make: I said in #661 that “It sounds like Grenier’s work . . . which surely is a point in its favor–that is, despite being minimalist, and–in the view of stasguards–worthless, there’s something about it that makes it recognizable as a particular poet’s.” It is by Robert Grenier, but my recognition of it as his wasn’t as close to being a point in its favor as I said. I not only had seen it before, but recently more or less studied it, for it was among the poems from Grenier’s Sentences that Silliman had in In the American Treethat I carefully read over and quoted parts of in an essay I’d been working on. I probably had read about it in Silliman’s blog, too. As well as read it years ago when I first got Silliman’s anthology.

I still claim my recognition of who composed the poem is evidence that there’s something to it, something identifiably unique to its author, which a poem of no value at all would not likely have. Otherwise, I probably wouldn’t have connected it to any particular poet.

I must confess, too, that I now remember not thinking much of “JOE” when I first saw it. Indeed, my reaction to it wasn’t much different from that of the stasguards. However, annoyed by their ignorant dismissal of it, I reflected on it more. It hasn’t become a super favorite of mine, but I now perceive its virtues.

Silliman’s comments helped me, although I also thought little of them, too, at first–I thought he liked the poem for the wrong reasons. I still have major differences with what Silliman says, but no longer feel he’s so much wrong as simply not coming at the poem from the slant I am.

My main problem with what he said was that I didn’t see the first “Joe” as a title. According to the look of the poem in the Silliman anthology, though, it would seem to be a title. There, it is among a sequence of poems excerpted from Sentences with a little row of asterisks between each poem. Most of the poems start with a short line of word without caps, but every once in a while one of them has an all-capital word above the rest of its text that seems to be a title. While I would never agree that the poem therefore “undermines everything people know or, worse, have learned, about titles,” I agree that the first “JOE” is a title–and maybe the second is, too. Grenier treats his title more interestingly than most poets treat theirs, but where does he under- mine the notion that a poem’s title tells you what it’s about, or anything much else about titles? Silliman ought to have spelled out just what he thinks titles are, and how Grenier undermines everything people know about them.

I reject Silliman’s assertion that Grenier’s text “undermines everything people know or, worse, have learned, about . . . repetition, rhyme, naming, immanence.” That it rhymes is nonsense. If it did, then substituting “Gwendolyn” for “Joe” would result in a much greater rhyme than Joe/Joe is.) That it repeats, and that that is the source of its effect is clear, but I can’t see that it is undermining any view of repetition I, for one, have ever had. What it does is make more poetic use of repetition than a poem by anyone I know of since Stein told us what a rose is. Grenier names like anyone else, too. No undermining there. Immanence may be a different story. Silliman uses the word a lot, but I haven’t read him enough sufficiently to know what he means by it as a critic nor do I have time now to find out, so I’ll ignore it, for now.

Silliman is a revolutionary whereas I’m an aesthete. So he sees under- mining that he’d probably term political where I see poetic creativity. He finds this poem to “challeng(e) the status of the title”; I don’t. I suppose you could say, as he does, that the poem sounds good–“Joe” contains the euphonious long o, and j-words apparently are feel good to say for the English-speaking. It’s not hard to pronounce but it allows one to use a lot of one’s pronouncing equipment. Hints of “joy” may accompany “Joe,” too, particularly when unexpectedly repeated, with nothing after it, to give a mind lots of space to find such things as “joy” near it. I wouldn’t term it especially beautiful, though. Finally, to finish comparing my thoughts on the poem to what Silliman said about it, I wouldn’t describe the two instances of “Joe” as hoveringly avoiding “a static balance” between the opposites he names, but that’s probably only a vocabulary difference between us.

Now, because the stasguards at New-Poetry mocked minimalist poetry in general as well as Grenier’s poem, I feel I ought to say some words in defense of minimalism. Minimalism in art has to do with focusing on details that are generally lost in larger complexities in both art and existence but which produce aesthetic pleasure once properly attended to. A painting that’s nothing but two colors, for example, will minimalistically force a viewer not superior to such things into the purity of color against color–and out of whatever the colors involved are secondary qualities of. A painting in one color only will make the viewer attend to the brushstrokes and or the texture of the canvas or its equivalent. Which may be a bore, but may also be startling interesting.

A minimalist work is nearly always more than it seems. That is, it nearly always includes its usually ignored context–as a painting or poem. A minimalist painting needs its frame or its location on a wall or in a book or the like for it to be questioned, then recognized, as an artwork; a minimalist poem needs its page and, perhaps, its book. I know I’m expressing myself sloppily, and I’m tiring, so I’ll go to “Joe,” which should make what I’m saying clearer.

The poem is just two words without its being in a book of poetry. Located there, however, the reader has to ask what it is, and assume it’s intended to be a poem. It’s about someone named Joe, presumably, but the only information about him it provides is . . . his name, repeated. Since it’s a poem, the repeated name must be saying something poetic about Joe. A background in poetry should readily provide a clue–once the reader softens enough to accept that the poem is telling him something, is saying that the text, “Joe,” is a poem about Joe. And that it is also admitting that that is all it can say about him. A reader with a background in poetry should soon remember the theme much-used in poetry of something’s being beyond the power of words to express. Joe? What can I say about him? He’s just . . . Joe. (Joe is a Joe is a Joe.)

A poem all of the text but one word of which is invisible.

To this the unconventionality of the poem should add under-images like the word, “joy,” I mentioned earlier. The reader can’t flow unreflectingly into amplification; he is arrested in the full semantic value, whatever it is, of “JOE.” The caps add “titledness” to the image of Joe–he is thus a kind of poem. The caps also underscore his being too large for words.

Among the poem’s other minimalistically realized (mostly visceral) meanings is how hugely, and finally, significant names can be. It might be said that, among much else, the poem is a tribute to titling. But it is finally most massively about the magnitude of a simple human being, something that two O’s as a poem ignore (as such a poem ignores the difference in expectedness–in a poem–between a repeated O and a repeated name–of a person already named). Which, to get back to the attempt at a parody I began my discussion, is why Graham’s is close to worthless–for anyone with the ability and background to appreciate minimalism.

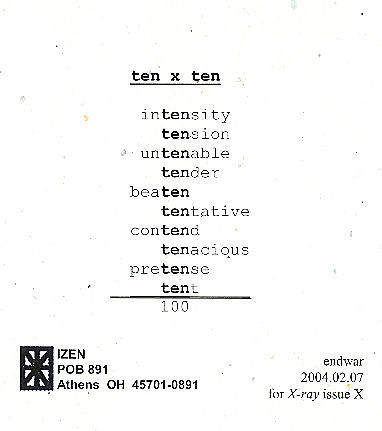

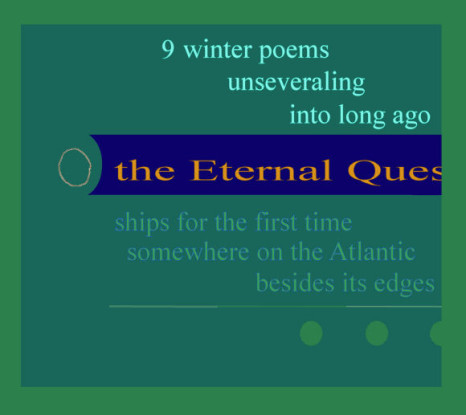

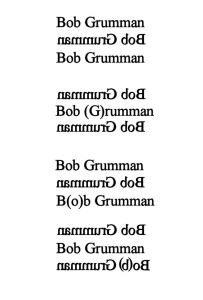

As I announced when I first posted this, I am hoping to publish an anthology of mathematical poems, like this one, so if you have one or know of one, send me a copy of it, or tell me about it.

As I announced when I first posted this, I am hoping to publish an anthology of mathematical poems, like this one, so if you have one or know of one, send me a copy of it, or tell me about it.

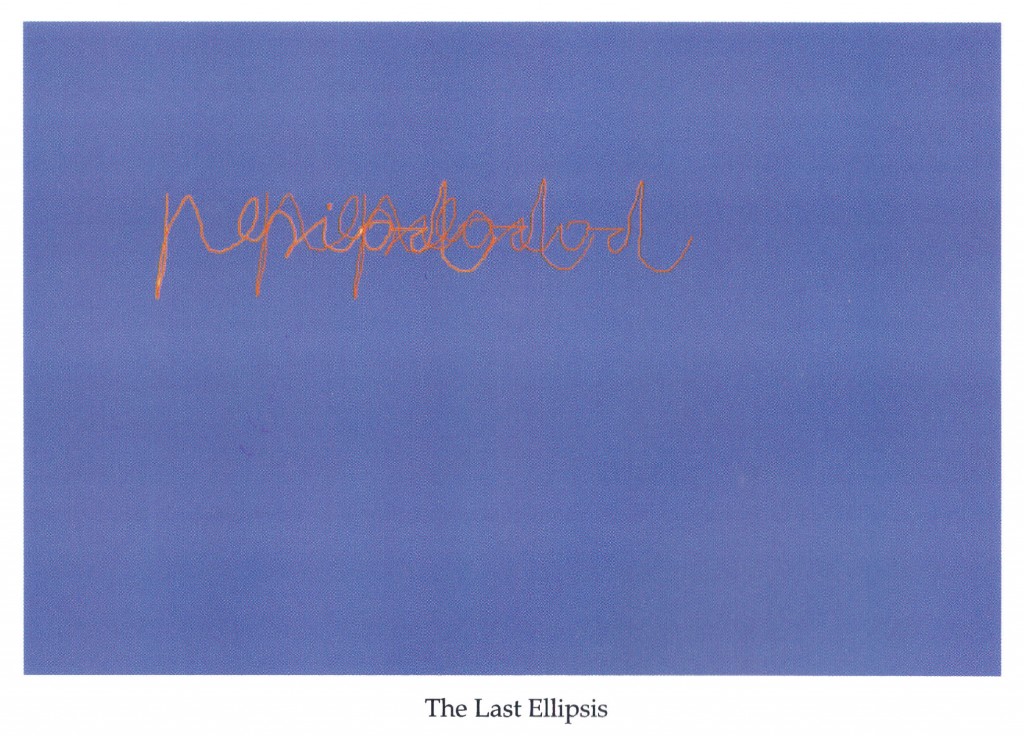

“certain kinds of semantically meaningless texts that somehow act like language are a form of visual poetry.”

what’s wrong with that?

actually, id be more interested in a report of marton’s presentation during his stay in this country.

As you ought to know by now, Nico, I have this absurd idea that poetry is a literary art, and therefore must have a semantic meaning. But I might have to accept certain kinds of “semantically meaningless texts that somehow act like language are a form of visual poetry” as poetry if there’s no other category for it. If it does something aesthetically interesting visually, then I’d call it “visimagery,” my word for visual art. If it is strictly textual but averbal, then, perhaps, “asemic poetry” would be the proper category for it. Justified by its having “near-words”–and having to have some category.

As for what I put in my blog, there’s a lot of stuff I’d like to see in it but am habitually too tired to post. I should be up to saying more about my day with Marton (and Clark) eventually, but not about Marton’s presentation, because I could only afford to stay a day, so missed it. It may have been recorded, though. By now he has probably given a second presentation in Chicago. His tour includes a third city–Milwaukee, I think. Anyway, he’ll be meeting Karl Young.

–Bob

–Bob

i know i stepped in your definition field, but wouldnt a “foreign” language be considered meaningless to someone without the semantic keys. though, of course, it would still be language.

im glad to hear marton’s visiting mr young..

thanks,

n

My impulse was to joke that all poems have to be in English. But in a way, that’s true: a poem is FOR ITS ENGAGENT a collection of wrods (and perhaps other elements) that he can read. A text in Spanish is not a poem for me, but can certainly be one for a person who speaks Spanish. Just as a painting can be a work of art for someone who can see but not for someone who is blind.

I maintain that everything has a personal definition and social definition. For me, a poem has to be in English. For the world, a poem has to be in some language more than one person can read.

It reduces to the silly philosophical question about whether real things exist where no conscious mind can witness them. I say they do simply because it’s easier to think things are stable, and don’t disappear when no one is looking at them. But the latter could happen. It doesn’t matter, though. Existence stays exactly the same regardless of what happens.

–Bob