Today was another bad day for me (because both my bikes had flat tires so I had to walk to where I had an MRI for my bad back, then walk to the bicycle shop two miles from there to get tubes before going on home, another two miles, so I’m just going to post one entry from my old blog, #631, in its entirety–because it’s one of my best entries for the general poetry public, I think:

24 October 2005: Well, we lost electricity in my neighborhood for seven or eight hours due to Wilma, but we got through it with minimal damage. Naples, to the south, didn’t do so well. Sad for them, but someone had to lose–and one good thing about the outcome is that the weather people seem to have been on top of things all the way through, which is certainly reassuring. In my ideal world there’d be hurricanes–but the land to persons ratio would be so high no one would have to live anywhere near places like Naples. There’d still be places like Naples, but they would be staffed by commuters, and lived in by vacationers. (Down with over-population–which in my book is anything over ten million–for the whole world.)

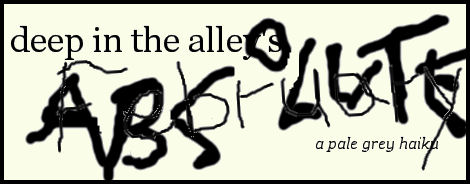

Okay, the poetry-related subject of this entry is the following poem:

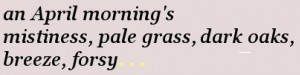

. 2 children’s

. rained-around dry quiet spot

. within forsythia

This, or something like it, was in my first book, poemns. After selling some of the copies of the book, I found something wrong with one of the other three poems on the sheet it was on, so removed the whole sheet from the remaining copies of the book. I think the printers failed to make a line in one of the poems go off the edge of the page as I’d intended it to. I should have a copy of the four poems somewhere but it’d take me a week to find them if I tried to, I’m sure.

I’ve used this poem elsewhere since the book, I believe. I want to discuss it here cbecause I consider it a near-perfect example of what I try for as a poet, which is simply to render, in as few words as possible, an image that will cause others as much pleasure as possible. This one accomplishes this through its (1) subject matter, which is (a) quotidianly likely to elicit most persons’ sympathy, (b) pretty, children generally coming off as cute, and forsythia as beautiful, (c) peaceful, the rain having to be little more than mist not to be getting through forsythia branches, and, most important, (d) archetypally resonant by representing Shelter and Companionship, as well as Spring (rain and forsythia, and human beings in their spring); and its diction, which includes the wonderful rained/round rim thyme (but, not, I’m sure that’s not original with me), the with/syth near-=rhyme and the dry/qui aft-rhyme (or whatever it is I’m calling traditional rhymes). Only now, by the way, did I realize that the latter rhymes were near- or full-rhymes. The poem is also effectively concise, and it draws on its being a haiku, for that adds haiku-depth to it (via what it picks up from the tradition, and all haiku before–and after–it).

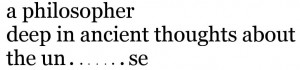

To me, one of its points of greatest interest is in what it does not have, mainly, manywhere-at-once, or equaphorical layering. In a way, this is a virtue, for it clarifies it into a moment of particular intensity. Amusingly, that emphasizes its being a pure haiku–albeit one without quite the right syllable-count. I do consider its lack of equaphors (or metaphors and the like), in the final analysis, a defect. I continue to believe the very best poems express two or more simultaneous images. But poetry as a whole would suffer consequentially if every poem were equaphorical.

Real life did inspire the poet, by the way. The forsythia in it is from the yard of the Hyde House, as it was known, on Harbor View Island in Norwalk, Connecticut, that I lived in between the ages of 7 and 12. It actually formed a sort of hut, though I’m not sure they could have kept out even mist. I played in it from time to time but most remember my sister Louise, a year younger than I, playing some kind of queen’s court game in it with her friends Ellen and Cindy.

Ironically, just the other day I learned that the Hyde House I’ve been reminiscing about is no more. It was leveled to make way for two condominiums that have to be devastating the ambiance of the shabby-genteel little clump of mostly vacation homes on the island. Progress triumphs again.

note: the large print is stupid, but I’m using it to indicate large blocks of quoted material because I haven’t been able to figure out how to indent at this site (other than use periods as with the poem quoted within my quote–which would take too long to get right for long prose passages).

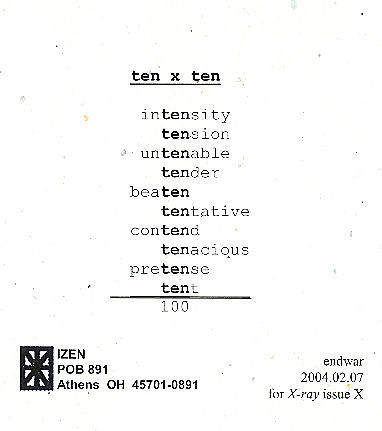

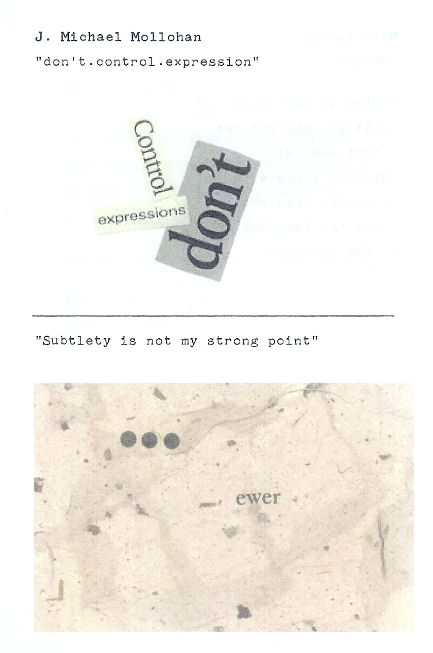

As I announced when I first posted this, I am hoping to publish an anthology of mathematical poems, like this one, so if you have one or know of one, send me a copy of it, or tell me about it.

As I announced when I first posted this, I am hoping to publish an anthology of mathematical poems, like this one, so if you have one or know of one, send me a copy of it, or tell me about it.

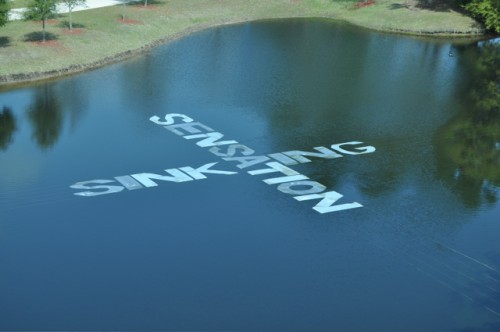

![DSC_1536[12]](/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/DSC_153612-e1302650888895.jpg)

Well, at any rate it appears to have been quite a sensation! Three of them!

– endwar