Entry 620 — Getting Enough Sleep

A little while ago (it is now around 9 P.M., 9 January) I was feeling good. I attributed this to my having gotten two naps today, one of an hour, the other of one or two hours. And I had gotten six hours of sleep last night, which is about as much as I generally get. I had just about finished backing up my blog entries and was very pleased at how good many of my poems seemed to me when I noticed them during the process. Unfortunately, I got the dates up my upcoming entries wrong, and in correcting them, lost what I had written for this entry. That pretty much wiped out my mood. I can’t stand screwing up like that, but I do it all the time!

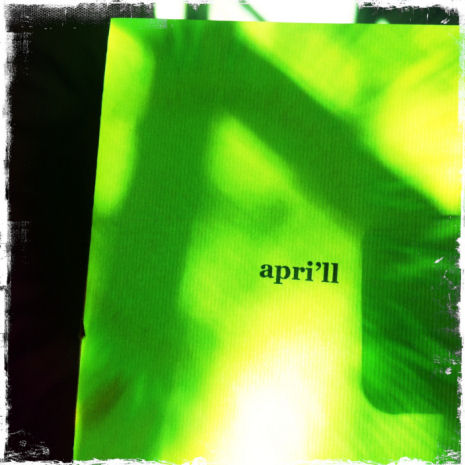

This is a pwoermd I stole from Geof Huth’s blog–because it has become too sophisticated to accept comments from dial-ups like my computer, and I wanted to comment on it. It’s by Jonathan Jones, lately of Brussels, but a citizen himself of the United Kingdom. What I like most about it is that it’s lyrical–as too many pwoermds are not. It wouldn’t be a visual poem for me, but an illustrated poem, except that I subjectively feel “apri’ll” is producing the wonderful colors of spring it is slanted into a portion of (through sheer will-power). Hence, in my taxonomy it is an infra-verbal visual poem.

.