Archive for the ‘Alan Shapiro’ Category

Entry 1120 — A Tough Night

Friday, June 14th, 2013

Last night I was up between 2 and 5 because my house flooded. A leak in my water heater. It turned out well, though: because I can’t afford a new heater, I’ll be without hot water. That means I don’t have a gas bill, anymore. As for hot water, well, it’s nice to have, but it’s a luxury, like the car I’ve almost never had. Very stressful, the leak, though–I was afraid for a while that a pipe under the house had burst. That would have been very expensive to fix.

I don’t believe I react well to stress, but I do suspect I may have an unusually high sensitivity to the signals my brain gives off when it approaches breakdown. Result: so far, I’ve always shut down before breaking down. That is, I go into my null zone rather than go absolunically wacko. My shell continues to do the everyday while the part of me that’s typing this basically gives up. Meanwhile, Chipper, the little blue bunny rabbit who is also part of me never stops reminding me, usually subverbally, that I’ve been in the null zone before and things have always gotten better. Dark thoughts occur, but never any plans for dark actions.

Well, I’m in my null zone again, so much so that the last two zoom-doses were unable to help me out of it. Ergo, I’m going to tread water for a while, again. I hope still to post one blog entry a day, but don’t expect to post any that’s more worth reading that a tweet.

.

Entry 792 — Analysis of an Iowa Workshop Poem

Saturday, July 7th, 2012

| Astronomy Lesson by Alan Shapiro The two boys lean out on the railing of the front porch, looking up. Behind them they can hear their mother in one room watching “Name That Tune,” their father in another watching a Walter Cronkite Special, the TVs turned up high and higher till they each can’t hear the other’s show. The older boy is saying that no matter how many stars you counted there were always more stars beyond them and beyond the stars black space going on forever in all directions, so that even if you flew up millions and millions of years you’d be no closer to the end of it than they were now here on the porch on Tuesday night in the middle of summer. The younger boy can think somehow only of his mother’s closet, how he likes to crawl in back behind the heavy drapery of shirts, nightgowns and dresses, into the sheer black where no matter how close he holds his hand up to his face there’s no hand ever, no face to hold it to. A woman from another street The boys edge closer, shoulder

|

THE IOWA WORKSHOP POEM:

1. involves quotidian, usually suburban subject matter, employing telling concrete details out of everyday life, accessibility being a key aim

the feel of the scene Shapiro depicts is suburban although sirens from “away deep in the city” can be heard, so the poem takes place either in suburbia or the outskirts of a city (and suburbia can have cities); its telling concrete details include tv programs, boys star-gazing, a woman in a street calling to her cat or dog

2. uses near-prose (i.e., free verse with few or no frills or unconventionalities of expression)

it has one simile, a nice one about “the black leaves of the maple/ where the street lights flicker/like another watery skein of stars.”

it also has a personification–“Ptolemies” as “astronomers”

no other figures of speech are in it, as far as I can make out

3. ends with a standard epiphany or anti-epiphany

here the epiphany is vague beyond subtlety but there: we human beans is just a “Name That Tune”-trivial flicker in the vastness of the universe. The poem is a haiku, really, extended for lines and lines.

4. is genteel in vocabulary and morality

unquestionably

5. strives for anthroceptual sensitivity (i.e., sympathetic awareness of other human beings)

Very much so, the scene depicted being entirely of inter-acting people almost but not enacting a narrative

6. acts as a means to self-expression, or bringing the self to life as opposed to capturing a scene, some object or idea–never as an end in itself, as a beautiful verbal artifact

This only somewhat applies. The self expressed is a distant observer; the scene–which includes both what’s going on and its emotional meaning–is more important than the observer.

7. the self brought to life is almost always a sensitive, politically-correct, average albeit cultured individual (the most extreme of Iowa Workshop Poems seem to be begging the reader to like the poem’s author)

Yes, behind the scene, sighing over the eternal meaninglessness of our life, but incompletely, slightly and certainly not intrusively

8. can be direct on the surface but aims for Jamesian subtlety in what its author would consider its most important passage

we know exactly what is going on; what is indirect is the meaning of it all, which I would not call Jamesianly expressed

9. is not controversial in thought or attitude, or–really–close to explicitly ideational

It doesn’t really convey a thought or attitude, simply reports, leaving it to the reader to interpret, as most good poems, and all Iowa Workshop Poems do.

10. is usually first-person

this one is not

11. is generally short–one page, although it can run to three pages.

this is a bit longer than most, but not long

12. wouldn’t be caught dead harboring a poetic technique not in wide use by 1950 at the latest

this could not be more the case.

I do not consider my analysis an evaluation of the poem, which I consider a good, appealing one, but one I think almost everyone interested in poetry will recognize as an Iowa Workshop poem. The best such poems are as good as the best poems of any other kind, I believe. But I distinguish between effective poems, like Shapiro’s, and important poems, like the best otherstream poems, because the latter add to the poet’s tool chest, as an Iowa Workshop does not. Not, I should add, that no poem can be both effective and important.

.

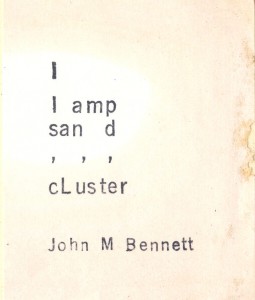

Bob,

this is hilarious!

Glad you like it, Conrad. Caleb Emmons seems soneone who knows wutzWut, for sure.

–Bob