Archive for the ‘Wallace Stevens’ Category

Entry 1097 — Wallace Stevens Poem

Sunday, May 19th, 2013

I’ve been having more problems with my computer. Am again emotionally exhausted. So, just a poem today–if I can paste it here (in my computer where I compose my entries) and then post the entry on the Internet.

It’s by Wallace Stevens:

THE HOUSE WAS QUIET AND THE WORLD WAS CALM

The house was quiet and the world was calm.

The reader became the book; and summer nightWas like the conscious being of the book.

The house was quiet and the world was calm.The words were spoken as if there was no book,

Except that the reader leaned above the page,Wanted to lean, wanted much most to be

The scholar to whom his book is true, to whomThe summer night is like a perfection of thought.

The house was quiet because it had to be.The quiet was part of the meaning, part of the mind:

The access of perfection to the page.And the world was calm. The truth in a calm world,

In which there is no other meaning, itselfIs calm, itself is summer and night, itself

Is the reader leaning late and reading there.

.

Entry 994 — “The News and the Weather”

Friday, January 25th, 2013

I’m reworking my last Wallace Stevens poem–the one in my most recent blog for Scientific American. Hence, I’ve been looking through Samuel French Morse’s great selection of his poems for passages to quote (or appropriate). As I was doing this earlier this morning, I came across the following:

THE NEWS AND THE WEATHER

I

The blue sun in his red cockade

Walked the United States today,Taller than any eye could see,

Older than any man could be.He caught the flags and the picket-lines

Of people, round the auto-works:His manner slickened them. He milled

In the rowdy serpentines. He drilled.His red cockade topped off a parade.

His manner took what it could find,In the greenish greens he flung behind

And the sound of pianos in his mind.II

Solange, the magnolia to whom I spoke,

A nigger tree and with a nigger name,To which I spoke, near which I stood and spoke,

I am Solange, euphonious bane, she said.I am a poison at the winter’s end,

Taken with withered weather, crumpled clouds,To smother the wry spirit’s misery.

Inhale the purple fragrance. It becomesAlmost a nigger fragment, a mystique

For the spirit left helpless by the intelligence.There’s a moment in the year, Solange,

When the deep breath fetches another year of life.

It immediately thought of what I thought would be a great little essay I could write about it and its use of the word, “nigger”–and about political correctness and freedom. I didn’t at once start it, though, for I had other things I wanted to get out of the way. But when, after an hour or so, I’d done that, I for some reason no longer had any urge to write my essay. Maybe some other time. The poem’s worth writing about, and so’s the word, “nigger,” which means several worlds, some of them wonderful, more than “disgusting sub-human.”

.

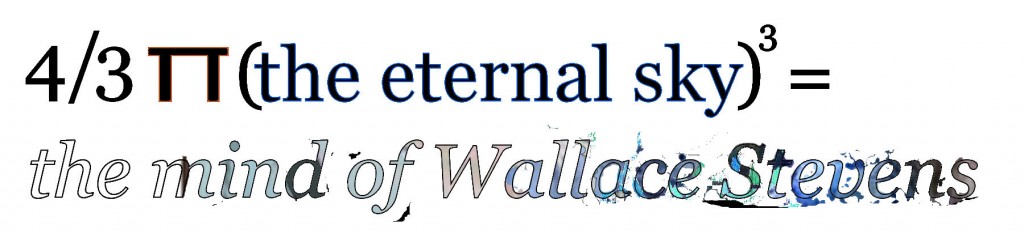

Entry 976 — “The Mind of Stevens”

Monday, January 7th, 2013

Pushing for material I can use in my Scientific American guest blog’s next entry, coming up this Saturday (and I’m very behind), I worked up the following from notes I scribbled a month or more ago and didn’t then get inspired enough by to base a poem on:

I love it, I hope not only because I just made it–smoothly–and tend to like stuff of mine I just made smoothly. Now to go to my Scientific American blog entry to explain why it’s so terrific.

.

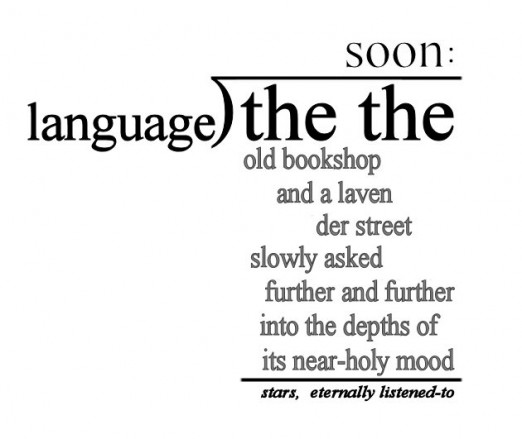

Entry 372 — Mathemaku Still in Progress

Tuesday, February 8th, 2011

If I ever come to be seen worth wide critical attention as a poet, I should be easy to write about, locked into so few flourishes as I am, such as “the the” and–now in this piece, Basho’s “old pond.” I was wondering whether I should go with “the bookshop’s mood or “a bookshop’s mood” when Basho struck. I love it!

If I ever come to be seen worth wide critical attention as a poet, I should be easy to write about, locked into so few flourishes as I am, such as “the the” and–now in this piece, Basho’s “old pond.” I was wondering whether I should go with “the bookshop’s mood or “a bookshop’s mood” when Basho struck. I love it!

Just one word and a trivial re-arrangement of words, but I consider it major. (At times like this I truly truly don’t care that how much less the world’s opinion of my work is than mine.)

We must add another allusion to my technalysis of this poem, describing it as solidifying the poem’s unifying principal (and archetypality), Basho’s “old pond” being, for one thing, a juxtaphor for eternity. Strengthening its haiku-tone, as well. But mainly (I hope) making the mood presented (and the mood built) a pond. Water, quietude, sounds of nature . . .

Oh, “old” gives the poem another euphony/assonance, too.

It also now has a bit of ornamental pond-color. Although the letters of the sub-dividend product are a much lighter gray on my other computer than they are on this one, the one I use to view my blog.

Entry 47 — Solution of a Cryptographiku

Friday, December 18th, 2009

The Four Seasons

.

3 31 43 73 5 67 3 61 43 67 67 19 41 13 1 11 19 7 31 5 3 12 15 21 4 19 3 18 15 19 19 9 14 7 1 6 9 5 12 4 8 21 25 33 9 30 8 28 25 30 30 16 24 14 4 12 16 10 21 9 64 441 625 1089 81 900 64 784 625 900 900 256 576 196 16 144 256 100 441 81

.

Today, the solution, with an explanation, to the above.

1. Each line says, “clouds crossing a field.”

2. A reader should know from its looks and the fact that it is a cryptographiku that it is a coded text. He should try simple codes at first on all the lines, the way one would in order to solve a cryptogram. If he’s familiar with my other cryptographiku, he will know I’ve more than once used the simplest of numeric codes. Such is the case here, in line 2. The code is 1 = a, 2 = b, etc.

3. The codes used for the other lines are harder to figure out, but the lines themselves give an important clue as to what they say: they each consist of four words, the first six letters in length, the second eight, the fourth one (which would almost certainly be “a”) and the fourth five. That ought to make one guess that each repeats the decoded one. As each indeed does.

4. It should be evident that the code for the fourth line uses the squares of the numbers in the code for the third. The basis of the arrangement of numbers in the third line will probably not be easy to guess.

5. If you consider what kind of numbers are being used in a given line, and are at all mathematical, you will realize that the numbers used in line one are all primes, with the first prime, 1, representing a, the seond prime, 2, representing be, and so on.

6. The next step is trickier but also requires one to think about kind of numbers. It turns out that the numbers used for the code in line three are the non-primes in order, with first of them, 4, representing a, the second, 6, representing b.

7. The surface meaning of the lines and the kinds of coding they’ve been put in is now known. All that remains is to find if a larger meaning in intended (yes) and, if so, what it is, and what the logic behind the coding is (and the kind of coding used in a cryptographiku is, by definition, meaningful. Wallace Stevens, whom one familiar with my poetry and criticism will know is important to me, helps with the last of these questions. Stevens wrote many poems (“Man on the Dump,” for instance) meditating on the idea that winter is pure reality, summer poeticized reality. Or, winter is primary, so can be metaphorically thought of a consisting of prime numbers only. Spring, by this reasoning, can logically consist of all the (lowest) numbers, summer of only factorable numbers, numbers that can be reduced to simpler numbers–expanded, poeticized numbers. Autumn, the peak of the year because it yields the fruit of the year, consists of summer’s numbers squared, or geometrically increased.

8. The final meaning of the poem is derived from its repetition of the simple nature scene about the clouds. A reader aware of Robert Lax’s work (and he will, if he’s familiar with mine), will know that he has a number of poems that repeat words or phrases–to suggest, among much else, ongoingness, permanence, undisturbable serenity. My hope is that this poem will make a reader feel the change of seasons within the grand permanence that Nature ultimately is. A constant message, in different coding as the seasons change.

9. All this should lead to “Whee!”

5. The decoded text uses a technique Robert Lax pioneered in to convey a meaning I consider archetypally deep, like the meanings Lax’s similar poems have for me.

6. The final meaning of the poem is (a) Nature is eternally changing; and (b) Nature is eternally unchanging. When I saw I could make iti say that, I got a thrill! I consider this poem one of my best inventions–even though I’m not sure it works as a poem.

Have fun, kids!

Entry 46 — Clues

Thursday, December 17th, 2009

The Four Seasons

.

3 31 43 73 5 67 3 61 43 67 67 19 41 13 1 11 19 7 31 5 3 12 15 21 4 19 3 18 15 19 19 9 14 7 1 6 9 5 12 4 8 21 25 33 9 30 8 28 25 30 30 16 24 14 4 12 16 10 21 9 64 441 625 1089 81 900 64 784 625 900 900 256 576 196 16 144 256 100 441 81

.

Today, just some helpful clues toward the solution of the cyrptographiku above:

1. A cryptographiku is a poem in a code. The code chosen and the way it works has metaphorical significance. The text encoded is generally straight-forward.

2. There are three codes used here, one of them very simple, the other two simple if you are mathematical.

3. The codes were chosen to illustrate a theme of Wallace Stevens’s, to wit: winter is reality at its most fundamental, summer is winter transformed by metaphorical layering.

4. Note that each of thr three lines is the same length, and divided into three “words,” each the same length of the homologous “word” in the other two lines.

5. The decoded text uses a technique Robert Lax pioneered in to convey a meaning I consider archetypally deep, like the meanings Lax’s similar poems have for me.

6. The final meaning of the poem is (a) Nature is eternally changing; and (b) Nature is eternally unchanging. When I saw I could make ti say that, I got a thrill! I consider this poem one of my best inventions–even though I’m not sure it works as a poem.

Have fun, kids!

I really like this one; it strikes me as very E.E. Cummings-inspired, and I love that guy. I think the use of gray is a good idea because it gives the “remainder” more punch at the end. I’m a bit confused on reading your description in which you keep talking about Basho’s pond, which I don’t see in evidence here … I’m thinking if I had seen an earlier version of this, or I was better versed in the Grummanverse, I would understand that. And finally, you won’t have to struggle between “the” or “a” bookshop’s mood soon, where there’s just one bookshop left. Just had to end that with a little (sad) humor!

Oh, boy, I get to explain! Nothing I love more. Basho comes in because of his famousest poem, which I’ve made versions of and written about a lot, the one that has the “old pond” a frog splashes into. My poem has an “old bookshop” that has a mood with depths a street enters like (I think) the pond’s water with depths the frog enters. But now that you bring it up, I guess the allusion is pretty hermetic.

Glad you like it. I still do now that I’m looking at it again–although it strikes me as pretty weird.