Archive for the ‘Geof Huth’ Category

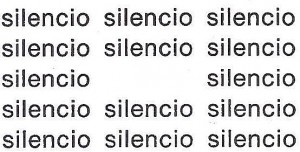

Entry 1553 — Back to “Silencio.”

Friday, August 29th, 2014

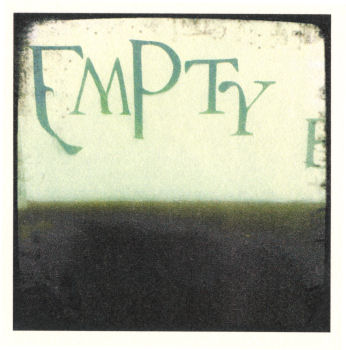

Entry 1552 — Another from Kalligram

Thursday, August 28th, 2014

This one’s by Geof Huth:

One of many interpretations of this is that it expresses my present melancholy about all the musts of my life that have turned to mist–do, needless to say, to missed opportunities (and mussed opportunities). The addition of the thick portions to the letters is, by the way, an extremely deft move. The F seems appropriate but I don’t know why. The beginning of some standard salutation?

.

Entry 1207 — The Experioddicist, July 1993, P.4

Sunday, September 8th, 2013

Note: I consider Geof’s poem a masterpiece–one of more than a few he’s done I wish I’d done.

.

Entry 644 — My Annual Birthday Present from Geof

Friday, February 3rd, 2012

Every year Geof Huth posts some kind of “homage” to me on my birthday–which, as everyone should know is 2 February, Groundhog Day, the same as James Joyce’s and Ayn Rand’s. The same as Tom Smothers’s, too! And just a tick from Gertrude Stein’s, 3 February, I’m relieved to say. The one he just posted here may be his best yet. It consists of a series of dictionary definitions of words having to do with my personal life (such as “connecticut,” the state I was born in) and my obsession with defining poetics (and the universe). Very funny, in good part because of his cruelly accurate understanding of me.

.

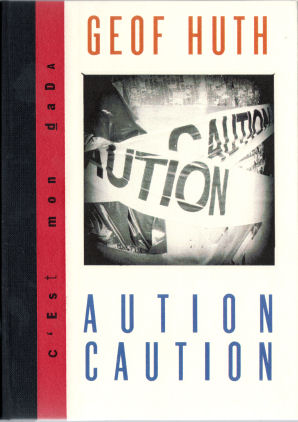

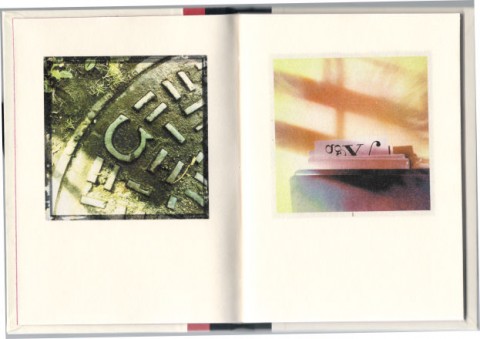

Entry 603 — c’est mon dada

Saturday, December 24th, 2011

Geof Huth recently sent me a Christmas package with a bunch of neat things in it, including the 4-inch by 6-inch hardbound book whose cover is shown directly below:

The first three images within were “Vers t ehen,” by Klaus-Peter Dencker, “Chretiens,” by Pierre Garnier and “Word Theatre,” by Theo Breuer.

I very much liked just about all of them. I thought they were photographs taken by Geof of text-fragments and things that Geof thinks look like typography, for he has taken a good deal of such photographs over the years. On the last page of the book, however, its contents are described as “collection of visual poetry, experimental texts and works influenced by Dada and Fluxus” followed by a list of works by title and author. But there are fifteen or twenty fewer works shown in the book than listed so I’m not sure who did what. And I noticed just about nothing that had any particular artist’s stamp on it. I guess that’s what Dada is s’posed to be.

Oops, now I have it: the collection is no doubt of some 65 (!) little collections like this one that the redfoxpress (of Ireland) published! Geof is #65, which is stamped on the back cover. So I was right to begin with. I’ll leave my errors uncorrected–examples of dada criticism.

New dogma of mine: a photograph whose subject is a word or words is a photograph of a word or words, not a visual poem. I’m not sure that’s right, though. I will have to think about it.

Diary Entry

Friday, 23 December 2011, 3:30 P.M. I haven’t felt like running for ages but forced myself to do a mile this morning. I took off when my watched was at the zero seconds mark but forgot to see how many minutes past seven it was when I took off. My finishing time was X:02. I’m guessing it was 11:02 since my last time was 11:17, and I felt I was a little better this time out–though still horrible. I only ran about twenty yards before having to really push every step to keep going. It’s a mystery to me why I’m so off–I feel reasonably untired playing tennis, and I don’t just stand on the court. As for my cultural productivity today, I puttered around in my response to Jake Berry’s essay but didn’t catch fire. I was, as usual, feeling too tired to do much. I may work some more on it. (Later note: I didn’t.) Right now, though, I’m going to lie down again.

.

Entry 598 — “Fifty”

Monday, December 19th, 2011

This is from Geof Huth’s blog:

I liked this when I first saw it although I didn’t find it saying anything verbally. When I finally realized it said, “fifty,” I thought it accidental because I couldn’t see why it would say that. My slow mind eventually remember that Geof is now fifty-years-old, which makes this image a particularly effective representation of his present strange combination of freedom and awkward incompleteness . . . straining, yearning for something. With his ego (“I,” as Karl Kempton would be sure to notice) lost or transcended.

Diary Entry

Sunday 18 December 2011, 6 P.M. Another unproductive day. Tennis in the morning, a fine meal at Linda’s in the afternoon. A blog entry for today just taken care of a little while ago. A little work done on my “Mathemaku for Scott Helmes” to count as “work on preparation for the A&H exhibition.” And now I’d like to go to bed, but will probably read instead.

.

Entry 409 — Thoughts on Poetics

Sunday, March 27th, 2011

The following is from Geof Huth’s ongoing “Poetics”:

84. Lie

Does the voice make a lie of the poem? Because a good voice can make a weak poem seem strong and a poor voice can ruin a great poem. Is the poem isolated on the page (the screen) the most accurate version of the poem, true to itself, or does the voice we use to read it in our heads also ruin great poems and resurrect the dead ones?

It comprised his blog entry for Friday. Here’s my reply:

Interesting question. I lean toward considering any poem on paper to its completion as the printed score of a musical composition is to its completion.

I can’t see a bad reading spoiling a good poem or good reading rescuing a bad poem, for me, but that’s because the conceptual area of my brain is much stronger than its auditory area. So, for me, what a poem is on paper is something like 95% of what it is, completed. For others the percentage will be lower or higher.

Since I can’t read music very well, a musical composition on paper is likely less than 15% of what it is, completed, for me. For Beethoven, in his final years, it would have been 100%.

Similar thinking applies to the font-shape and color of a poem’s print, and the color and texture of the paper.

All this is out the window for sound poetry and visual poetry–well, not all of it for those of us for whom poetry is a verbal art requiring completion by being spoken, whether internally by the poem’s engagent or externally by either the engagent or someone else. No more than half out the window, I would say. For me, a verbally effective visual or sound poem can be neither completely spoiled nor completely rescued by its extra-verbal visual or auditory components–but it could be one or the other by its verbal content–as a poem.

Hey, thanks, Geof. I’ve just written my blog entry for Sunday.

–Bob

Still later comment: I wonder if it’s possible for a bad poem to be read so well it becomes, or seems, a good poem. It seems to me that if it can be read in such a way that its sounds good, it must be good–it had whatever is needed to be beautifully voiced.

Entry 161 — A Huthian Fidgetglyph

Saturday, July 17th, 2010

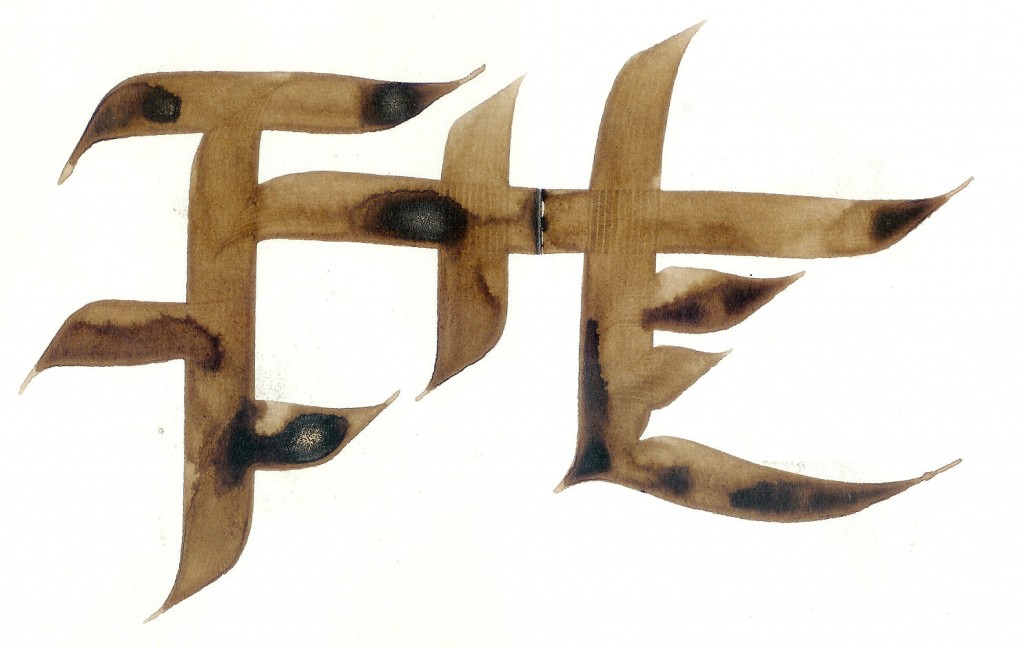

In one of his recent mailings to me, Geof Huth sent a folded card with the interior of ther First reformed Church of Schenectady, New York, shown on its 300th birthday in 1980. I’m showing it here because it sets up the fidgetglyph Geof had drawn across the inside of the card and given the title “The Fervent F.” I’m showing that because it seems to me how good a calligrapher Geof is at his best. The original is much better than the image shown here, by the way.

Entry 118 — Geof Huth’s Collected Pwoermds

Monday, March 15th, 2010

I haven’t started my trip yet. My body conked out before I could–some kind of virus, I guess. So I’m still at home. Should be leaving in a couple of days.

I was feeling too lousy to post anything here for two or three days, and wouldn’t today, either, although I feel a lot better. However, today I got a copy of Geof Huth’s NTST, the subtitle of which is the collected pwoermds of geof huth. It’s perfect for a blog entry because I can quote whole poems from it quickly, and because I found some pwoermds I can be quickly insightful about. So, here’s one page:

an/atomy

shadowl

rayns

watearth

upond

psilence

These pwoerds are absolutely representative of the many (hundreds?) pwoermds in the collection, which I mention in case anyone suspects I chose them to show him at his very best. Two thoughts: that he misspelled “psylence,” and that “shadowl” is such an especially good pwoermd that it ought to be on a page by iself. The selections on this page are intended, I’m sure, to be stand-alones, but they also look like and work as a five-line poem. That I find “sahdowl” better clearly by itself is ironic, for I’ve several times opined that while pwoermds could occasionally be terrific, they work best as part of longer poems.

Oddly, I find evidence for this (in my opinion) on the very next page of NTST:

Pebbleslight

stilllllife

I like it much better as “pebbleslight stilllllife.” Of course, with the title (and Geof defines pwoermds as one-word poems without a title), one still reads pebbles into the still life. I just like the linkage closer. I’d like a detail or two more, too–really, I’d like a full-scale haiku using “pebbleslight stilllllife.” Which is absolutely not to say I don’t extremely like the piece exactly as Geof has it.

Oh, NTST was published in England by if p then q (apparently not an offshoot of Geof’s dbqp press). Its website is at www.ifpthenq.co.uk.

Entry 83 — MATO2, Chapter 1.05

Saturday, January 23rd, 2010

About a week later I heard from one of my California writer friends, Moya Sinclair, who called me a little after eight in the evening sounding very cheerful and energetic. She, Annie Stanton, quite a good linguexpressive poet, Diane Walker, well-known as a television actress under her maiden name, Brewster, who had literary ambitions and was quite bright but never to my knowledge broke beyond the talented dabbler stage, and I had been a few years earlier the main members of a little writers’ group at Valley Junior College in the San Fernando Valley presided over by Les Boston, a professor there. Technically, we were doing independent studies with Dr. Boston, but in reality we friends who met weekly to discuss one another’s writing, mine at the time plays. Annie and Diane were about ten years older than I, Moya close to eighty by the time of her phone call, and she was in a convalescent home. Her circulatory system had slowly been wearing out. I fear she died there, for I never heard from her again. Both Annie and Diane died around then in their early sixties, huge unexpected losses for me.

Moya reported that Annie had been over for a visit and had left my book with her. Moya said she’d been reading parts of it and found it beautifully written, etc. She had a few adverse comments on it, too–on Geof’s word for one-word poem (“pwoermd”), for instance, but that was to be expected. Moya, for years working on an autobiographical novel, was pretty wedded to the old standards. We had a fine chat that boosted my spirits a good deal. She represented one of the main kinds of readers I hoped would like my book.

A day later I got a very positive letter from Jack Moskovitz about my book, and a lukewarm one about it from Geof. Geof, as I remember, felt I should have lightened up on the Grummaniacal coinages. I think he was right. I believe one of the things I tried to do in my two revisions of the book was to cut down on them.

The next day, according to my diary, I got lots of letters, mostly from people I sent my book to, and for the most part complimentary though Jody Offer, a California poet/playwright friend of mine, felt I got too advanced in parts–I’m sure in part because of my terminology. I was finding out, though, that my book was not as geared for non-experts as I’d hoped.