Posts Tagged ‘theoretical psychology’

Entry 115 — The Knowleplex

Saturday, February 27th, 2010

The knowleplex is simply a chain of related memories–A.B.C.D.E., say–or a knowledge-chain. It is what we remember whenever we are taught anything, either formally at school (when our teacher tells us Washington is the capital of the United States, for instance) or informally during day-to-day experience (when we see our friend Sam has a pet cat).

There are three kinds: rigiplexes, flexiplexes and feebliplexes, the name depending on the strength of the knowleplex. One is too strong, one too weak, and the other just right. If we let A.B.C.D.E. stand for “one plus two is three,” then a person with a rigiplex “inscribed” with that, asked what one plus two is, will quickly answer, “three.” But if asked what one plus four is, he will give the same answer, because his rigiplex will be so strong it will become wholly active due only to “one plus.”

On the other hand, a person with a feebliplex “inscribed” with “one plus two is three,” asked what one plus two is, will answer “I dunno,” because his feebliplex will be so weak, even “one plus two is” won’t be enough for his knowlplex to become active. Ditto when asked what one plus four is. But the person whose knowleplex is just right–whose knowleplex is a flexiplex, that is–will answer the first question, “three,” and the second, “I dunno.”

Needless to say, this overview is extremely simplified. Even “one plus two is three” will form a vastly more complicated knowleplex than A.B.C.D.E. The strength of a given knowleplex will vary, too, sometimes a lot, depending on the circumstances when it is activated. And each kind of knowleplex will vary in strength, some feebliplexes being almost as strong as a flexiplex, for example. In fact, a feebliplex can, in time, become a rigiplex. For the purposes of this introduction to knowleplexes, however, all this can be ignored.

Entry 89 — IQ, EQ and CQ

Friday, January 29th, 2010

I’m taking a break from Of Manywhere-at-Once to reveal my latest coinages, PQ and CQ, or psycheffectiveness quotient and creativity quotient. I’ve long held that IQ is a ridiculously pseudo pseudo synonym for intelligence. “Pychefficiency” is an old term of mine for “genuine intelligence.” A slightly new thought of mine is that PQ equals IQ times CQ divided by 100. So an average person’s PQ would be 100 times 100 divided by 100, or 100. The most common Mensa member’s PQ would be 150 times 50 divided by 100, or 75.

Okay, mean-spirited hyperbole. But there definitely are a lot of stupid high IQ persons, and it is the stupid high IQ persons that gravitate toward Mensa membership. (Right, I’m not in Mensa–but I could be, assuming my IQ hasn’t shrunk much more over the years than my height, which is down a little over half an inch.)

My formula wouldn’t come too close to determining a person’s true PQ because IQ is so badly figured, but it would come at least twice as close to doing so as IQ by itself. A main change necessary to make the formula a reasonable measure of mental effectiveness would be to divide it into short-term IQ and long-term IQ. The former is what IQ currently (poorly) is–i.e., something that can be measured in a day or less. The latter would be IQ it would take a year (or, really, a lifetime, to measure). Quickness at accurately solving easy problems versus ability to solve hard problems.

Really to get IQ right one would have to measure the many kinds of intelligence there are such as social intelligence, aesthetic intelligence, athletic intelligence, self intelligence and so forth, then add them together, find the mean score thus obtained for human beings. Divide that by a hundred and use the answer to divide a given intelligence sum to find true IQ.

Maybe not “true IQ,” but “roundedness quotient.” For me, true IQ would be all the intelligences multiplied together divided by the product of one less than the number of intelligences and 100. That, on second thought, wouldn’t do it, I don’t think. What I want is a reflection of the strength of all one’s cerebral aptitudes without penalty for absent talents since it doesn’t seem to be that they’d be too much of a handicap. I’m in an area now I need to think more about. So here will I close.

Entry 78 — Of Manywhere-at-Once, Volume Two

Monday, January 18th, 2010

For three months or so I have been critiquing a book by an imbecile who doesn’t know who wrote the works of Shakespeare, only that Shakespeare did not. Diana Price’s Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography. Each day (but one) I’ve attacked a section of it at HLAS, where the authorship debate can be carried on without restrictions. I started the critique for many reasons, the main one being that the book is too full of crap to ignore. Nor did I ignore it when it was first published. I read it through, making copious annoyed and sarcastic annotations in it. I wrote up an overview of its main thesis for use in my own authorship book. And I fully intended to write a thorough critique of it–which I never got around to. Until now.

2009 was a terrible year for me, especially the second half of it. I did almost no writing during that second half. So my second reason for my critique was simply to force myself into a writing routine. I have to admit I also wanted something to express anger about, being pretty unhappy at the time with just about everything in my life. In other words, take out my misery on poor Diana Price. Not a worthy victim but published hardbound by a more respectable company than I ever was, and asked to lecture on her book at universities, as I never have been asked to lecture on my Shakespeare book. Oh, what I’d really call my main purpose is to present a full-scale portrait of a propagandist–that is, reveal what the main propagandistic devices are and how they work. A handbook on propaganda for the uninitiated, or–more exactly–the incompletely initiated–which would include me, out to learn in the process.

My venture has so far been successful. My critique is now almost 40,000 words long, and I’m almost halfway through Price’s books, which I’m covering page by page. For some reason today I thought of a similar project I could start here: constructing day by day another book I have notes for and long ago seriously hoped to write but didn’t, my Of Manywhere-at-Once, Volume Two. (I’ve had a third volume in mind to do, as well.)

So: tomorrow I’ll begin it. I figure I’ve pretty much taken care of this entry already–and want to add something to it that has nothing to do with my manywhere book, but want to record in case I forget about it. It has to do with my knowlecualr psychology, specifically with my theory of temperaments. Until an hour or so ago, I posited four temperaments (or personality-types): the rigidnik, the milyoop, the ord, and the freewender for, respectively, high-charactration/low accommodance persons, high-accommodance/low charactration persons, medium charactration/medium accommodance (ordinary) persons, and high charactration/high accommodance persons. My types were based on two of my three mechanisms of intelligence, charactration and accommodance. I suddenly saw earlier today that a fifth temperament based on the third mechanisms of intelligence, accelerance, might be in order. A person high in accelerance bu not high in either of the other two mechanisms. An eruptor? Not sure how good a name that is, but it will do for now.

Entry 42 — A Knowlecular Analysis of the Visiophor

Monday, December 14th, 2009

#682 through #688 contain pieces of an attempt at an analysis of how, according to my knowlecular theory of psychology, we experience visual poetry. It’s a jumble I hope at some time to make a coherent essay out of but for right now I’ve made it a page you can access by clicking on “How the Brain Process Visual Poetry” in the Pages section to the right.

Entry 17 — Knowlecular Poetics, Part 1

Wednesday, November 18th, 2009

Today, #621 in its entirety because I’m too tapped out to do anything more:

| 14 October 2005: Eventually, neurophysiology will be the basis of all theories of poetics. My own central (unoriginal) belief that metaphor is at the center of (almost) all the best poetry is neurophysiological, finally, for it assumes that the best poems happen in two (or more) separate brain areas, one activated by an equaphor (or metaphor or metaphor-like text), the other (or others) by the equaphor’s referents. Manywhere-at-Once. Neurophysi-ologists may even now be able to test this idea–although not with much finesse. Their instruments are too crude to determine anything definitively, but could certainly determine enough to be suggestively for or against my idea.

I believe, by the way, that the few good non-equa-phorical poems get most of their punch due to their evasion of metaphor. That is, those experiencing them get pleasure from the unexpected absence of metaphor or nything approximating mataphor. It may even be that such poems cause those experiencing to experience anywhere-at-Once by activating two separate brain areas–one of them empty! (A kind of “praecisio” for Geof Huth to consider.) The pay-off would be a feeling of image-as-sufficient-in-itself.Be that as it may, I brought this subject up–well, I brought it up because I couldn’t think of anything else to discuss today. But I wanted to begin considering visual poetry neurophysiologically, something I haven’t before, that I know of. Recently, I’ve been trying, in particular, to distinguish visual poetry from illustrated poetry in terms of my knowlecular psychology, which is entirely neurophysiological (although the neuorophysiology is hypothetical). I’ve been having trouble. I believe I have a beginning, though. It is that an illustrated poem, like some of William Blake’s, put a person experiencing them in a verbal area of his mind first, and then into a visual area of his mind. The text activates his verbal area, the illustration his visual area–at about the same time that his verbal area activates some of the cells in the portion of his visual area activated by the illustration. This results in a satisfying completion that enhances the pleasurable effect of the poem. A classical visual poem–a poem, that is, that everyone would consider a visual poem–will put a person experiencing it in a verbal area of his mind and a visual area of his mind at the same time. Because the text and the illustration will be the same thing. The activated visual area will cause (minor) pain, because not expected–that is, it will be due to textual elements used in unfamiliar ways, or graphic elements jammed into texts in unfamiliar ways. If successful, the poem’s verbal content will secondarily activate some of the cells in the portion of the subject’s visual area the visual elements did–to result in the same kind of saisfaction the illustrated poem resulted in, except faster (the precipitating experiences not being consecutive but simultaneous), and with more unfamiliarity resolved, a plus in my theory of aesthetics. Apologies if all this seems dense. I’m feeling my way–and writing for myself more than for anyone else. I hope to find my way to clearer expression, eventually. |

Apologies for the misplacement of the above text: I can’t figure out how to indent at this site.–Bob

Entry 4 — The Nature of Visual Poetry, Part 2

Thursday, November 5th, 2009

Note to anyone dedicatedly trying to understand my essay, you probably should reread yesterday’s segment, for I’ve revised it. Okay, now back to:

The Nature of Visual Poetry

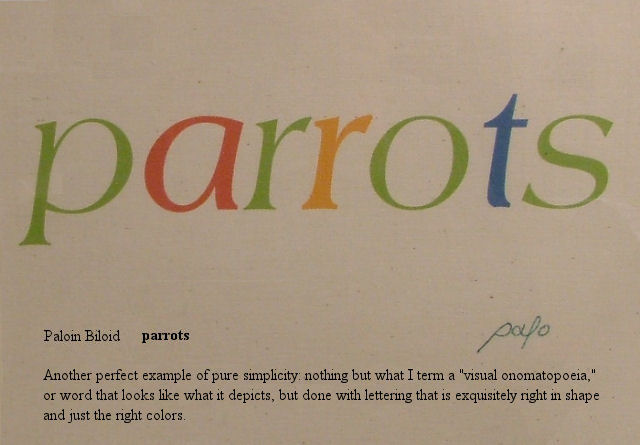

As a visual poem, Biloid’s “Parrots” is eventually processed in two significantly different major awarenesses, the protoceptual and the reducticeptual. In the protoceptual awareness, the processing occurs in the Visioceptual Awareness, to which it directly proceeds. In the reducticeptual awareness, it first goes to the Linguiceptual Awareness, which is divided into five lesser sub-awarenesses, the Lexiceptual, Texticeptual, Dicticeptual, Vocaceptual, Rhythmiceptual and Metriceptual. The first is in charge of the written word, the second of the spoken word, the third of vocalization, the fourth of the rhythm of speech and the fifth of the meter of speech. Of these, the linguiceptual awareness passes “Parrots” on only to the first, the lexiceptual awareness, because “Parrots” is written, not spoken. Since the single word that comprises its text will be recognized as a word there, it will reach its final cerebral destination, the Verbiceptual Awareness.

The engagent of “Parrots” will thus experience it as both a visioceptual and a verbiceptual knowlecule, or unit of knowledge–at about the same time. Visually and verbally, the first because it is visual, the second because it is a poem and thus necessarily verbal. Clearly, it is substantially more than a conventional poem, which would be processed entirely by its engagent’s verboceptual awareness.

Okay, this essay, only about a thousand words in length so far, is already a mess. Yes, way too many terms. And I keep needing to revise it for clarity. Or, at least, to reduce its obscurity. I have trouble following it myself. My compositional purpose right now, though, is to get everything down. Later, I’ll simplify, if I can.

Entry 3 — The Nature of Visual Poetry, Part 1

Wednesday, November 4th, 2009

The image above is from the catalogue of a show I co-curated in Cleveland that Michael Rothenberg was kind enough to give space to in Big Bridge #12–with two special short gatherings of pieces from the show, with commentary by me. I have it here to provide relief from my verosophizing (note: “verosophy” is my word for serious truth-seeking–mainly in science, philosophy, and history). It’s also a filler, for I’ve had too tough a day (doctor visits, marketing, phoning people about bills) to do much of an entry.

It’s not a digression, though–I will come back to it, as a near-perfect example of a pure visual poem.

Now, briefly, to avoid Total Vocational Irresponsibility, back to:

the Nature of Visual Poetry

The pre-awareness is a sort of confederacy of primary pre-aware- nesses, one for each of the senses. Each primary pre-awareness is in turn a confederacy of specialized secondary pre-awarenesses such as the visiolinguistic pre-awareness in the visual pre-awareness and the audiolinguistic pre-awareness in the auditory pre-awareness. Each incoming perceptual cluster (or “pre-knowlecule,” or “knowlecule-in-progress,” by which I mean cluster of percepts, or “atoms of perception,” which have the potential to form full-scale pieces of knowledge such as the visual appearance of a robin, that I call “knowlecules”) enters one of the primary pre-awarenesses, from which it is sent to all the many secondary pre-awarenesses within that primary pre-awareness.

The secondary pre-awarenesses, in turn, screen the pre-knowlecules entering them, accepting for further processing those they are designed to, rejecting all others. The visiolinguistic pre-awareness thus accepts percepts that pass its tests for textuality, and reject all others; the audiolinguistic pre-awareness tests for speech; and so on. More on this tomorrow, I hope.

Entry 2 — The Ten Knowlecular Awarenesses

Tuesday, November 3rd, 2009

Okay, today the first installment of my discussion of the nature of vispo, which begins with a summary of my theory of “awarenesses”:

A Semi-Super-Definitive Analysis of the Nature of Visual Poetry

It begins with the Protoceptual Awareness. It begins there for two reasons: (1) to get rid of the halfwits who can’t tolerate neologies and/or big words, and to ground it in Knowlecular Psychology, my neurophysiological theory of psychology (and/or epistemology). The protoceptual awareness is one of the ten awarenesses I (so far) posit the human mind to have. It is the primary (“proto”) awareness–the ancestor of the other nine awarenesses, and the one all forms of life have in some form. As, I believe, “real” theoretical psychologists would agree. Some but far from all would also agree with my belief in multiple awarenesses, although probably not with my specific choice of them. It has much in common with and was no doubt influenced by Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences.

The protoceptual awareness deals with reality in the raw: directly with what’s out there, in other words–visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory, gustatory stimuli. It also deals directly with what’s inside its possessor, muscular and hormonal states. Hence, I divide it into three sub-awarenesses, the Sensoriceptual, Viscraceptual and Musclaceptual Awarenesses. The other nine awarenesses are (2) the Behavraceptual Awareness, (3) the Evaluceptual Awareness, (4) the Cartoceptual Awareness, (5) the Anthroceptual Awareness, (6) the Sagaceptual Awareness, (7) the Objecticeptual Awareness, (8) the Reducticeptual Awareness, (9) the Scienceptual Awareness, and (10) the Compreceptual Awareness.

The Behavraceptual Awareness is concerned with telling one of one’s behavior, which this awareness (the only active awareness), causes. For instance, if someone says, “Hello,” to you, your behavraceptual awareness will likely respond by causing you to say, “Hello,” back, in the process signaling you that that is what is has done. You, no doubt, will think of the brain as yourself, but (not in my psychology but in my metaphysics) you have nothing to do with it, you merely observe what your brain chooses to do and does. But if you feel more comfortable believing that you initiate your behavior, no problem: in that case, according to my theory, your behavraceptual awareness is concerned with telling you what you’ve decided to do and done.

The Evaluceptual Awareness measures the ratio of pain to pleasure one experiences during an instacon (or “instant of consciousness) and causes one to feel one or the other, or neither, depending on the value of that ratio. In other words, it is in charge of our emotional state.

The Cartoceptual Awareness tells one where one is in space and time.

The Anthroceptual Awareness has to do with our experience of ourselves as individuals and as social beings (so is divided into two sub-awareness, the egoceptual awareness and the socioceptual awareness).

The Sagaceptual Awareness is one’s awareness of oneself as the protagonist of some narrative in which one has a goal one tries to achieve.

The Objecticeptual Awareness is the opposite of the anthroceptual awareness in that it is sensitive to objects, or the non-human.

The Reducticeptual Awareness is basically our conceptual intelligence. It reduces protoceptual data to abstract symbols like words and numbers and deals with them (and has many sub-awarenesses).

The Scienceptual Awareness deals with cause and effect, and may be the latest of our awarenesses to have evolved.

Finally, there is the Compreceptual Awareness,which is our awareness of our entire personal reality. I’m still vague about it, but tend to believe it did not precede the protoceptual awareness but later formed when some ancient life-form’s number of separate awarenesses required some general intelligence to co:ordinate their doings.

I have a busy day ahead of me, so will stop there.