Archive for the ‘Taxonomy’ Category

Entry 1733 — A Limited Entry

Monday, February 23rd, 2015

Okay, maybe I shouldda said “more limited than usual.” I’ve had a busy day away from the computer–with nothing I was sufficiently burning to say to inspire a good entry, anyway. So, just a minor thought followed by Knowlecular Psychology stuff I’ve written about before but want to repeat to get my brain a little more well-fastened to it.

* * *

Thinking about my tendency to try too hard to make sure my readers had all the information they needed fully to understand what I was writing, it occurred to me technology could come to my aid: I’m sure Kindles could be fixed to allow me to avoid boring any reader with information he doesn’t need could but also provide him with a text he could click to at any time which would have all the extra information. Right now footnotes can do this, but what I’m speaking of would not be intrusive the way footnotes are.

Indeed, a reader could be given a choice of texts–one with the math explained, one without that, for example; or any other appropriate specialized version.

* * *

Re: my knowlecular psychology, I was thinking again about what most poems are about, and went through my list again: (1) people; (2) imagery sans people; (3) concepts . . . Is that all? Doesn’t sound right, but I’m too out of it right now to think of any others.

What knowlecular psychology has to do with this, is that the first category could be described (as I’m sure I’ve more than once already described it) as “anthroceptual poetry.” Or as “sagaceptual poetry,” which is poetry in which what happens to one or more people is more important than the people–for the reader, the joy of vicariously experiencing a human triumph is more important than the joy of empathetically merging with another human being. Two kinds of people poems.

By imagery poetry, I mean poetry that is more concerned with conveying the beauty of the sound and/or the visual appearance (primarily or usually) of what is denoted by a poem’s words–or protoceptual poetry. As for concept poetry, I’m not sure any kind of genuine poetry is more conceptual than either of the other two (and almost all poems contain both anthroceptual and protoceptual matter). If it existed, I would call it “reducticeptual poetry.” A good example would be “lighght”: it is aesthetically dependent on its conceptual element–the conceptual datum about its orthography; but that element’s only use is to metaphorically lift the image the poem is about into, well, poetry, so I consider the poem more protoceptual than reducticeptual.

It may be that certain conceptual poems do use conceptual elements to lift a content that is ideational rather than sensual into poetry. Indeed, perhaps one of my mathematical poems may provide some reader more with a feeling of the poetry of asensual mathematics than with anything sensual image that may be an element of the poem.

Something requiring more thought.

Note: what I wanted primarily to glue into my memory was the term “protoceptual.” I’ve had trouble with it because I for a while was using “fundaceptual” in place of it. Eventually I needed “funda” elsewhere in my psychology and felt it too confusing to have it there and with “ceptual,” so went back to “protoceptual,” which I used before for the term.

.

Entry 1402 — Something From The Eighties

Monday, March 24th, 2014

Note: hold down your control button and punch + to be able to read the following more easily.

Once again I needed something to post here and grabbed this from 25 years or so ago. It didn’t get me into the BigTime. Note: “vizlation” was my word then for “visimagery,” which is my word now for “visual art.

.

Entry 1347 — Another Late Entry

Tuesday, January 21st, 2014

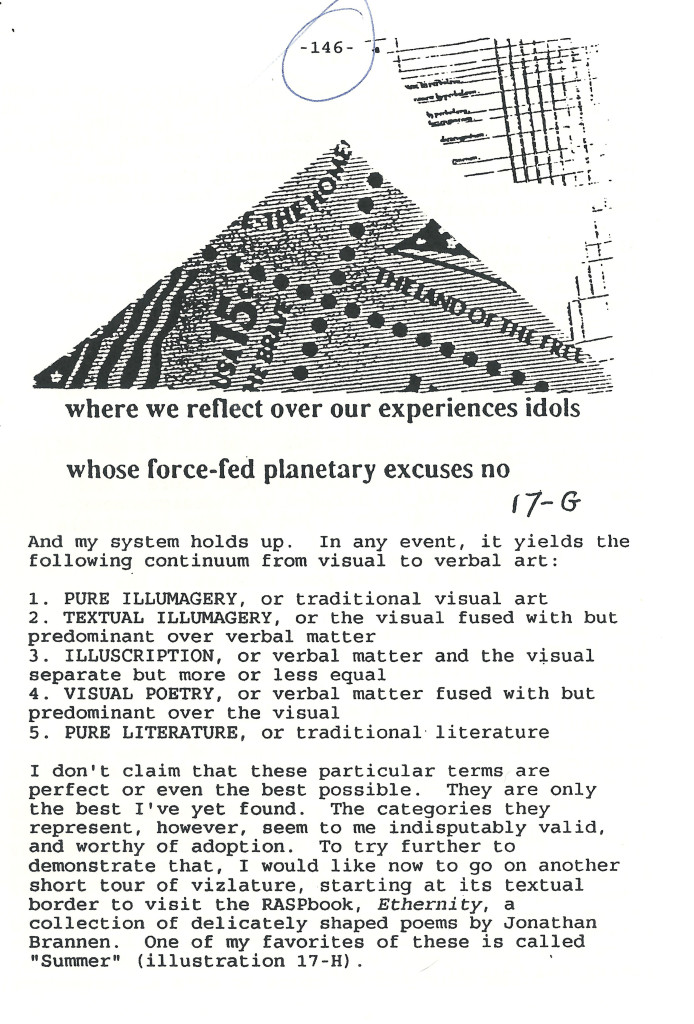

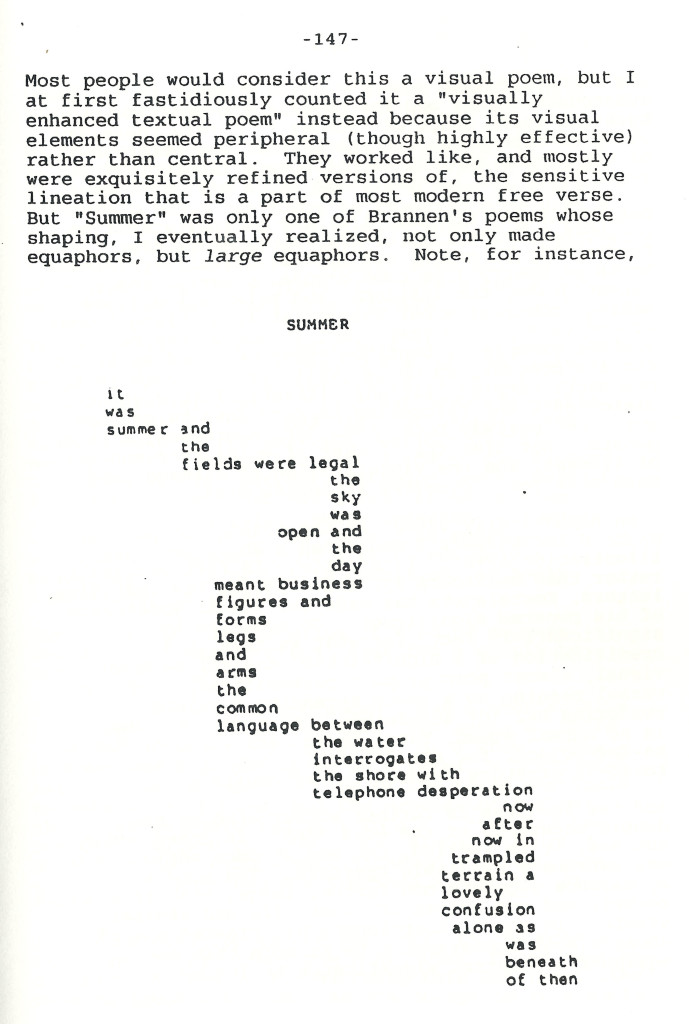

My absentmindedness is getting worse, it would seem, although it was pretty bad to begin with. Anyway, here is yesterday’s entry, just thrown together a day late. It’s some pages from Of Manywhere-at-Once that I don’t have time to comment on:

.

Entry 1290 — AudioTextual Art, Part 1

Thursday, December 5th, 2013

One of my many problems as a would-be culturateur is biting off more than I can chew. Today, for instance, I needed something for this entry. My laziness struck first, telling me to just use the graphic immediately below:

It’s from Mark Sutherand’s Sonotexts, a 2-DVD set he recently sent me–with a copy of Julian Cowley’s user’s guide to sound poetry from Wire. As soon as I saw what Mark had sent me, I went into one of my yowie-fits, perceiving it, as I wrote Mark, as a sort of class in sound poetry, something I’d been wanting to come to terms with for years. I had visions of taking a fifteen-minute class in the subject based on Mark’s package–something I’ve followed through on for four or five days now, except my requirement isn’t fifteen minutes daily of immersion, just a significant immersion that might last only a few minutes–like the amount of time it took me to read the text and above and study the graphics.

I had a second yowie-fit concerning my use of the above here, which I suddenly saw as the first step in a Great Adventure, Bob Grumman’s Quest to Assimilate Audio-Texual Art. (Not “sound poetry” because I had already realized my subject would cover more than sound poetry.) I would write a book here, one Major Thought per daily entry that would not just describe my attempt to learn about sound poetry and advance the World’s understanding of the whole range of audio-textual art, but expose the World to my theory of aesthetics–down to its Knowlecular foundation. All while working on three or four other not insignificant projects daily. But I was not wholly unrealistic: my aim was “merely” a good rough draft, not a perfect final draft.

Well, maybe I’ll keep going for more than a few days. Perhaps I’ll even write something of value. For . . . ? One of the reasons I probably won’t get far is my belief, strengthening daily–if not hourly–that there are not more than a dozen people in the world able to follow me at this time, nor will there ever be, so I’ll be wasting my time. Yes, I do recognize that the reason for this may not be how advanced my thoughts are but how badly expressed and/or obtuse they are. No matter, I myself will enjoy writing about my adventure, and having it to write about may be enough to keep me in it until I’ve actually accomplished my main aim, an understanding of audio-textual at that makes sense to me.

Ergo, here’s lesson one, which an enlargement of the text above from the booklet that comes with Mark’s set will facilitate:

Its words, of course, are Mark’s.

Student Assignment: two words or more concerning “Sound Poem for Emile Berliner”–prior to listening to it. Not much to say except for taxonomical remarks unsurprising to anyone who knows me. First off, since there can be nothing in the composition anyone will be able to recognize as verbal, as far as I can now see, I would term it “linguiconceptual music,” “linguiconceptual” being my term for asemic textual matter in an artwork that conceptuphorically (or provides a concept that metaphorically) adds appreciably to the work’s aesthetic effect. I will say more about this after hearing the composition. Right now I don’t see how its textual content can be evident without a listener’s simply being told that it is there.Unless the tracing is exhibited as the composition is being played, as it seems to me it ought to be, and maybe is! The tracing IS a visual poem, albeit a simple one that serves the work as a whole as its caption.

No, it’s more than that–the textual music is metaphorically its voice, which makes it an integral part of the composition that is secondarily a caption for it.

So much for lesson 1. (I think I passed.)

.

Entry 1248 — What a Poem Is

Thursday, October 24th, 2013

I can’t seem to get into this value-of-poetry topic so for now will simply deal with the terminology I came up with several days ago and thought would get me going deeper. I’ve pretty much junked all of my previous related terminology. The new terminology should cover everything it did.

First of all I have ordained that a poem hath:

Fundamental Constituents:

1. words as words, and punctuation marks and verbal symbols like the ampersand and mathematical symbols like the square root sign, or the verbal constituents of poetry;

2. words as sounds, or the auditory constituents of poetry–which can, in the case of sound poetry, include averbal sounds;

3. words as printed objects, or the visual constituents of poetry–which can, in the case of visual poetry, include averbal graphics.

I tentatively would also include negative space, by which I mean not only the blank page words are printed on but the silence their sounds can be said to be printed on, as fundamental constituents of poetry.

Every poem contains all four of these constituents. Taken together, they form the poem’s denotative layer, which expresses what the poem explicitly means. That layer in turn generates the poem’s connotative layer, which expresses what most people would find it implicitly to mean. Note: if the poem is plurexpressive–a visual or sound poem, for instance–its graphics or sounds would contribute to both layers: a drawing of a house would denote a house, for example, and the sound of a gunshot would denote a gunshot. (“Gunshout,” I mistyped that as, at first. Aren’t words fun?!)

The two layers together make up what I’m now calling a poem’s expressifice. (“Boulder”–“bolder” with a u added. Sorry, I began wondering if I could–oops, that’s “cold” with a u added–make a Kostelanetzian list of words like “gunshout.” I didn’t intend for the longer word to be a regular wourd. . . .)

Back to “expressifice.” It is responsible for what a poem says. Okay, nothing new except the Grummanisms so far. Recently, and this is an area I must but probably won’t research, there has been some grappling with the idea of “conceptual poetry” that I have found important and interesting, but confusing. My next “poetifice” is the conceptifice. My Merriam Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary provides a definition of “concept” that I find satisfactory for my purposes: “an abstract or generic idea generalized from particular instances.” In a poem, it would be close to what I’ve used the term, “unifying principal,” for. A poem’s “meaning” seems to me a near-synonym for it, too.

I can’t see that it’s any less “expressed” by a poem than connotations are, and I mention that because my impression is that those discussing conceptual poetry generally oppose it to “expressive poetry,” by which they basically mean “what a poem says” rather than the meaning of what a poem manifests.

It now occurs to me that what the conceptual poets are doing is minimalizing what I call their poems’ expressifices to magnify their conceptifices. If so, my term should be more useful than I at first thought it would be. I feel it of value anyway because of the great difference between what it can be said to express and what the expressifice can.

As I wrote that, I realized that the entire conceptifice of many poems, particularly the most popular ones is not very ideational–is, in fact, just a large connotation. Basho’s famous frogpond (“frogpound?”) can help here, I think (and I’m a bit foggy about where I’m going, but think I’m getting to someplace worth getting to). Here’s my translation of it:

‘

old pond . . . . . . the sound of a frog splashing in

.

This poem may have more valid, interactive unifying principals per word-count than any other poem ever made. So its conceptifice includes the idea of “the contentment the quiet portions of the natural world can provide one.” Or is that an image? In any case, it seems different in kind to a seond idea it clearly presents: “the wide range in magnitude (in all meanings of the word) of the universe’s moments.” We feel the first, we . . . ideate? the second–while feeling it, yes, but in a another way, in another place in our brains, than we do the serenity the first component of the poem’s conceptifice is about. Poetry, and poetry-become-philosophy.

I will have to come back to this.

The final three poetifices are the aesthifice, the anthrofice and the utilifice. These have to do the meaningfulness of a poem’s initial meanings. Every poem has all three of these, but usually one is emphasized at the expense of the other two.

The aesthifice has no meaning, it just is. (See MacLeish.) It is meaningful for its expression of sensual beauty. It can’t help but express other things, but they are trivial compared with the beauty of its sounds and/or sensual imagery and/or feelings it is most concerned with. In my notes about it I mention “beauty of constituents,” “imagery” (and “deep imagery,” possibly. “freshness of expression,” “archetypality,”display of skill” and “patterning.” There are more, probably many more.

The anthrofice has no meaning, either, but is primarily concerned with human beings, their actions and emotions. It expresses what I call “anthroceptual beauty,” the beauty of human love, for instance. Narrative poetry aims for anthrofices, lyric for aesthifices. Then there’s the utilifice. It does mean. A rhymed text you value because of what you learned from it will feature a utilifice. Beauty of any significance is besides the point, what counts is that what one gets goes beyond what the poem is–the poem is a helpful step toward attaining something more valuable than it whereas a lyric or narrative poem is art for art’s sake. In short, I categorize a “poem” whose utilifice is dominant as a form of utilitry–either informrature if conveying information, or advocature if telling people what to do. Lyric and narrative poems are forms of art.

If I weren’t such a lump, I’d now apply the above to actual poems. As a matter of fact, that’s what I want to do in my November Scientific American blog entry. Right now, though, here’s a rhyme that isn’t a poem:

Count that day lost Whose low descending sun Views from thy hand No worthy action done.

It’s from a wall of my high school cafeteria. I don’t know who wrote it, but I like it a lot-–and believe in it! A pretty rhyme but didactic, so not a poem. Its function is not to provide pleasure but to instill (however pleasantly) a valuable rule of conduct.

All of a poem’s poetifices taken together are a . . . poem, a lyrical poem if the poem’s aesthifice is dominant, a narrative poem is its anthrofice is dominant, and a utilitarian poem is its utilifice is dominant.

* * *

Well, I did a lot better than I thought at the start. It needs more work but I’m satisfied with it as is.

.

Entry 1084 — Yet More Mathpo Thoughts

Thursday, April 25th, 2013

In the March entry of my Scientific American blog, I praised a poem of Rita Dove’s–with chagrin, because she’s one of poetry’s enemies, in my view, due to her having the status to bring the public’s attention to poetry outside of Wilshberia but doesn’t. Here’s what I said about her “’Geometry,’ which wonderfully describes the poet’s elation at having proven a theorem: at once, her ‘house expands,’ becoming transparent until she’s outside it where ‘the windows have hinged into butterflies . . . going to some point true and unproven.’ Putting her in the almost entirely asensual beauty of the visioconceptual part of her brain where Euclid doth reign supreme.” I bring this up to illustrate an important reason for my emphasis on the idea of a mathexpressive poem’s doing mathematics. It is, that if one of my long division poems does not do mathematics, there is nothing to distinguish it from a poem like Dove’s. If that makes taxonomical sense to anyone, so be it, but it doesn’t to me.

Needless to say, I very much want it believed that my poems do something special, but that doesn’t make my belief that they do necessarily invalid.

Going further with the idea of the value of doing something non-verbal in a poem rather than just discussing some discipline in which non-verbal operations occur, the possibility of doing math in a poem simplies the possibility of doing other non-literary things in them. Like archaeology. I’ve tried that in a few of my visual poems (as have others, whether consciously or not, I don’t know). I’ve suggested archaeology sites to what I believe is metaphorical effect, but only portrayed archaeology, not carried out archaeological operations. Not sure yet how that can be done but feel it ought to be possible. Ditto doing chemistry–as some have, I believe (although I can’t think of the unusually-named poet who I believe has, right now).

I’ve read of choreographical notation and feel confident that it could be effectively used in poetry. Don’t have time to learn it, my self, though. I’ve done music in poems–only at the simple level that I’ve done mathematical poems, but made poems that require the pocipient to be able to read music to appreciate them. There are all kinds of wonderful ways to go as a poet for those believing other ways of interacting with the world besides the verbal can be employed in poetry rather than merely referred to, however as eloquently as Rita Dove has referred to the geometrical.

.

Entry 1083 — More Mathpo Blither

Wednesday, April 24th, 2013

I believe I’ve worked out my final argument for considering mathematical operations to happen in my mathexpressive poems:

(1) Consider the sentence, “It is the east and Juliet is the sun.” The sun is presented as a metaphor for Juliet but it remains an actual sun.

(2) Consider the equation, “(meadow)(April) = flowers.” The mathematical operation of multiplication is presented as a metaphor for the way April operates on a meadow, but it remains an actual mathematical operation of multiplication. The equation carries out the operation of multiplication on two non-mathematical terms to get a third non-mathematical term. It is something real that acts metaphorically.

If the mathematical operation does not occur, what happens? Two images, one of a meadow, one of April, whose collocation a reader is to take as having to do with flowers? What sort of poem would that be? Not that the actual mathematical operation makes it a great poem; I only use it because its simplicity makes my point so clearly.

That it is possible for such a thing as a poem that is part mathematical and part verbal to exist is important to me for taxonomical reasons since it helps substantially to allow me to claim all poetry ultimately to be of just two main kinds, lexexpressive poetry, which consists of nothing (or, sometimes, nearly nothing) but words (and punctuation marks), and plurexpressive poetry, in which one or more expressive modality is as aesthetically important in it as words (and punctuation marks): visioexpressive poetry, mathexpressive poetry, audioexpressive poetry and performance poetry (which I want to find a term for that carries on my “X-expressive” coining).

.

Entry 1065 — Behind Again

Saturday, April 6th, 2013

I waited until early afternoon before finally taking a caffeine pill. I just couldn’t get going. it’s a little after 5 now, and I’ve been zipping along, feeling content albeit not exuberant. I haven’t done anything of consequence yet, though, and this entry won’t be much: one of my “just-keeping-my-vow-of-an-entry-a-day” ones.

First off, here’s where my latest Scientific American guest blog entry is, although I’m sure all of you got my group e.mail about it. I have one sort of interesting thing to say about it. In one of my poems there my quotient is, “painter/ unsleeping/ a day long ago.” I saw when looking over the entry earlier today that most readers would probably interpret this as about a painter who is staying awake through some day long ago but what I meant and thought without thinking that I was saying was that the painter was in the act of unsleeping the long ago day. I was using an intransitive verb as a transitive verb. I did mention that in my entry but not because I thought anyone could take me to be writing about an unsleeping poet. Anyway, to make it clearer, although maybe not clear enough, I’ve changed my version of the passage to “painter/ unsleeping a/ day long ago.”

I have tentatively coined “bentword” to represent words like “unsleeping” which will derail readers. If they do so effectively, they will cause the simple pleasure of fresh language. Which I hope soon to discuss like I’ve just discussed rhyme, and various metaphors–including the verbaphor, another new coinage to go with my visiophor, mathephor and audiophor, as a kind of metaphor. I must be taxonomical complete, you know.

Well, my caffeine pill is wearing off, so that’s it for this entry.

.

Entry 1033 — Important Taxonomy Announcement

Tuesday, March 5th, 2013

At New-Poetry today, Al Filreis mad the following announcement:

Today we are releasing PoemTalk #63, a discussion of Laynie Browne’s Daily Sonnets with Sueyeun Juliette Lee, Lee Ann Brown, and Jessica Lowenthal:

..PoemTalk is available on iTunes (simply type “PoemTalk” in your iTunes store searchbox)..From the program notes:.PoemTalkers Jessica Lowenthal, Lee Ann Brown, and Sueyeun Juliette Lee gathered with Al Filreis to talk about five poems from Laynie Browne’s Daily Sonnets, which was published by Counterpath Press of Denver in 2007. We chose two of Browne’s “fractional sonnets,” two of the sonnets in which the talk of her children is picked up partly or wholly as lines of the poem, and one of her “personal amulet” sonnets. These are, to be specific: “Six-Fourteenths Donne Sonnet” [MP3], “Two-Fourteenths Sonnet” [

MP3], “In Chinese astrology you are a snake” [

MP3], “I’m a bunny in a bunny suit” [

MP3], and “Protector #2: Your Personal Amulet” [

MP3]. The sonnet after Donne is a constrained rewriting of a “holy” sonnet: “I am a little world made cunningly.”

.Al Filreis

After reading about the fractional sonnets, which sound like fun to me, I am giving up my lifetime view that a sonnet must consist of 14 rhyming iambic pentameters. There are just too many variations people are calling sonnets for my previous insistence to make sense. But we need a name to distinguish the traditional “real” sonnet from other poems called sonnets, so I ordain that such sonnets be called “classical sonnets,” and all other sonnets be called . . . “stupid sonnets.” Just kiddin’. I haven’t thought of a name for them yet.

(Yeah, yeah, who cares. But I wanted to show that I can change my mind.)

.