Archive for the ‘sonnet’ Category

Entry 1753 — My 1st Full-Scale Hero in Poetry

Sunday, March 15th, 2015

In my little-selling Of Manywhere-at-Once, Keats was one of the six canonized poets I wrote a chapter about. Yeats, Pound, Stevens, Cummings and Roethke were the others. I suddenly realize that Stevens was the last of them to become a hero in poetry of mine–around 35 years ago. None since. Nor, that I can think of, any literary heroes of any kind since then. Heroes of verosophy? Perhaps. More likely, no: because I don’t think I have any genuine verosophical heroes. The one who comes closest is Nietzsche, but I consider him a literary hero. I’ve greatly admired a lot of verosophers–Archimedes, Aristotle, Darwin, Newton, Dalton, Faraday, to mention a few–but not the way I’ve idolized and drenched myself in the works and lives of writers like Keats. And a number of visimagists like Cezanne and Klee. But no composers. I guess the reason for this is obvious: I’ve become a writer, and (to a degree) a visimagist, but not a composer. I consider myself a verosopher, but one unlike any I’m familiar with, except–possibly–Pierce.

It may be that I’ve had no cultural heroes since my thirties due to some flaw of mine, but I suspect one grows . . . not beyond, but off to the sides, of hero-worship. Into too much of one’s own work toward becoming a cultural hero oneself to have as much time new ones. One also will eventually have a number of contemporaries to take the place of heroes, albeit differently–as co-heroes rather than as worship-worthies.

In any case, in my chapter about Keats, I spent over four pages on his sonnet to Chapman’s Homer, which was one of the few poems I’d memorized by then (around the age of 18)–and, for that matter, one of the few I have ever memorized. I wish I’d memorized many more, but I also wish I knew more than one language. I tend to think I’ve stored all the data I’ve been capable of (as has everyone), so it doesn’t bother me inordinately. Just a little wishfulness that a few things were not impossible. Except when I’m in my null zone and realize that nothing really good is possible.

I only memorized one other poem by Keats (also at around the age of 18):

When I have fears that I may cease to be Before my pen hath glean'd my teeming brain, Before high-piled books, in charactry, Hold like rich garners the full-ripen'd grain; When I behold upon the night's starr'd face, Hugh cloudy symbols of a high romance, And think that I may never live to trace Their shadows, with the magic hand of chance; And when I fear, fair creature of an hour, That I may never look upon thee more, Never have relish in the faery power Of unreflecting love!--then on the shore Of this wide world I stand alone and think Till Love and Fame to nothingness do sink.

Note Keats’s glorification of “high-piled books” here and another poet’s accomplishment in the Chapman poem–his raw young poetic ambitions as a young man obvious, so just the thing to capture me at 18–besides the level of the writing. Although poetry was never at the center of my writing ambitions until the past decade or so, by default.

(Aside: after going through my edition of Keats’s poems to make sure I remember the poem above correctly–actually to fix parts I knew I hadn’t–the level of his writing bothered me: in less than 26 years he composed more effective poems than I have in almost 75. This is not false humility. But I feel I have added to the poet’s tool-kit, which he did not, and ranged beyond poetry into a theory pf psychology, which he did not, and which I think beyond doubt an accomplishment of sorts. Yes, competitiveness is an enduring part of my character. I still consider more a virtue than not.)

Okay, back to my dictum about reading poetry to the extent that you devour everything you can of the life and work of at least one of them as I devoured Keats. This resulted in several (but not a flood) of defective poems until I wrote the following in my twenties:

I yearn to run madly into the brush till a wild complexity of chance-created life has cut me off from mortals' petty strife I long to be where swift winds fill with the joyful fundamental music of woods & a gloriously unsymmetrified uproar of grass and violets and weeds and rocks covers every open field and curving hill. I long to stand at the sweet dense core of nature studying the clouds' slow schemes till the regulated world has blurred into nothingness & I am in leagues with dreams..

This is a fair derivative poem, I now think, but indicative only that when I wrote it, I had reached the basement of the poet’s vocation–thanks to all the reading I did. I’m afraid I have to admit that this lesson of mine isn’t much of a lesson, for if you need someone urging you to read poems and writings about poets before you’ll do it, all the reading you do will be a waste of time for you. I did the reading I did because I had to. and I had made a hero of Keats I had to find out as much as possible about, because of my genes, which made me search for a hero, then in effect become a sort of apprentice of his. The real lesson is that you should save time by dropping the idea of becoming a poet if you aren’t already automatically doing this. I suppose a minor implicit value of the lesson is to confirm you in your vocation if you have found your Keats–and encourage you to keep going if you have not, but are deeply involved with some kind of poetry.

.

Entry 1515 — Sonnet Revision

Tuesday, July 22nd, 2014

My adventures trying to get the following sonnet the way I wanted it was a major strand of my first full-length book, Of Manywhere-at-Once, 23 years ago:

Sonnet from my Forties Much have I ranged the major-skyed suave art The Stevens shimmered through his inquiries Into the clash and blend of seem and are And volumes filled in vain attempts to reach The heights that he did. Often, too, I've been To where the small dirt's awkward first grey steps Toward high-hued sensibility begin In Roethke's verse, or measured the extent Of hammered gold and wing-swirled mythic light That Yeats achieved, or marveled down the worlds That Pound re-morninged windily to life, And struggled futilely to match their works. Yet still, nine-tenths insane though it now seems, I seek those ends, I hold to my huge dreams.

The last chapter alone has five versions of it. I reworked it at least ten times in the next four or five years. Since then, I fiddled with at every few years and, for some unknown reason, took a stab at it again a few nights ago, ending yesterday with the version above. Who knows whether it will be my final version. Right now I dislike it slightly less than I dislike the other versions. I consider it a fascinating failure. If I ever finally finish the second volume of Of Manywhere-at-Once that I planned to have published a year after the first edition of volume one, I’ll explain in detail why I rate it as I do. (I also consider it brilliant, by the way.)

* * *

Here are two more entries to the list I posted yesterday:

No poetry written after the year X is any good.

No poetry written before the year X is any good.

A thought of my own: the popularity of serious poetry depends much more on what the people in it are doing than, say, what the language in it is. I elitistly believe that the more unanthrocentric (people-centered) a poem is, the better is it–and the less it will appeal to philistines. Sometimes.

.

Entry 1022 — A Change to the Sonnet

Friday, February 22nd, 2013

See if you can find what I changed–then figure out why I thought it worth making (which I haven’t been able to do):

Sonnet from My Forties

Much have I ranged the luminous deep art

that Stevens somehow miracled around

his meditations into seem and are,

and each time burned eventually to founda realm to equal it. I’ve often been

as well to where the small dirt’s first grey steps

toward high-hued sensibility begin

in Roethke’s verse, or measured the extentof wing-swirled, myth-engendering pure light

that Yeats achieved, or marveled down the worlds

that Pound re-morninged raucously to life,

and struggled fruitlessly to match their works.Yet still, nine-tenths insane though it now seems,

I seek those ends, I hold to my huge dreams.

I think it may be that I consider it a slight improvement in the meter. I was trying to lower the poem’s adjective-count, but wasn’t able to.

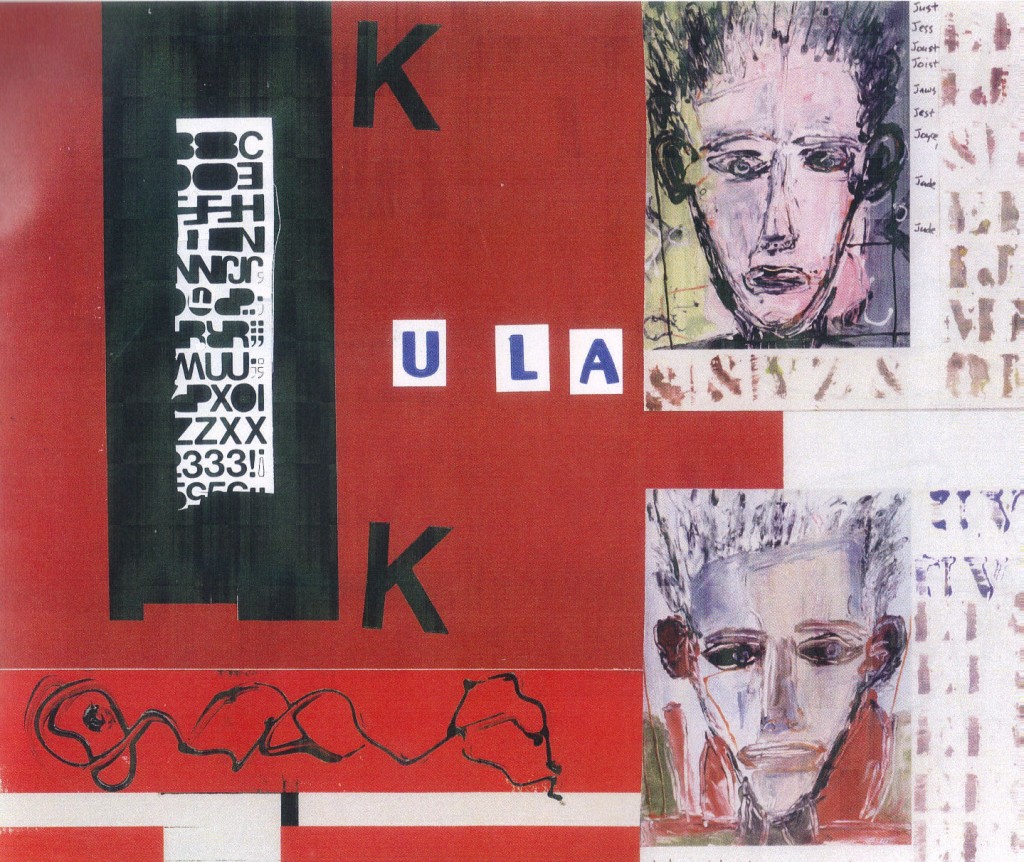

Now, to make up for the sonnet, here is another visocollagic poem be Guy R. Beining from the Do Not Write In This Space anthology I recently got from its editor, Marshall Hryciuk:

It’s untitled, but here I’m calling it “Kulak” because I hate untitledness.

.

Entry 1021 — The Never-Finished Sonnet Again

Thursday, February 21st, 2013

I noticed versions of it during my latest visit to previous blog entries that made me want to yet again try to perfect it, although I no longer think it has a chance of being anything of value:

Sonnet from My Forties

Much have I ranged the luminous deep art

that Stevens somehow miracled around

his meditations into seem and are,

and each time burned eventually to founda realm to equal it. I’ve often been

as well to where the small dirt’s first grey steps

toward high-hued sensibility begin

in Roethke’s verse, or measured the extentof wing-swirled, myth-electric, royal light

that Yeats achieved, or marveled down the worlds

that Pound re-morninged raucously to life,

and struggled fruitlessly to match their works.Yet still, nine-tenths insane though it now seems,

I seek those ends, I hold to my huge dreams.

Yeah, too many adjectives, too gaudy. I wonder what Hopkins or Dylan Thomas would have made of it. At the moment I think it’s the best of my attempts, though. I doubt I’ll think that a year from now.

.

Entry 824 — Critique, Continued

Wednesday, August 8th, 2012

Here’s my sonnet, again, back for further dissection

Much have I ranged the lolli-skied deep art

that Stevens somehow miracled around

his meditations into seem and are,

and each time burned eventually to found

a like domain. I’ve often ventured, too,

to where the weather’s smallest pieces, earth,

and earthlife synapsed in the underhue

of Roethke’s thought and felt no less an urge

to master his techniques, as well. And I’ve

explored the fading fragments of the past

that Pound re-morninged windily alive,

sure I would one day follow on his path.How vain they’ve been, how vain my fantasies:

their only yield so far just lines like these.

The first question of the day is whether or not the “mis-used” words are virtues or defects. They are “miracled” and “synapsed,” two nouns used as verbs. The noun-to-verb change happens all the time in English, yet there seem still to be people peopling the outskirts of provincialism whom it dismays. Of course, when one comes on a noun that’s been used as a verb for the first time in the one’s experience, it is bound to seem slightly wrong. In a poem, though, no one should object to this practice if the object is freshness. Which it almost always is in my poems. Still, one can over-do it. Whether I have with these two, and with the later “re-morninged,” which is both a noun used as a verb and a word given an unexpected prefix. “Re-morninged” may be strained, but I like it (and used it in all my versions of this poem) because it is also a metaphor for the particular way Pound brought the past “to life again.”

Then there are my coinages, “lolli-skied,” which I’ve already discussed, and “underhue,” which may well not be a coinage. If a coinage, it uses “under” as a prefix the same way Wordsworth did, so I consider it a plus. (If I were an academic, I’d quote the passages where Wordsworth used it, but I’m not–’cause I got more important things to do.) Again, whether these are plusses or minuses is a to each his own proposition.

I’m not sure what “seem” and “are” are the way they are used here. Verbs as nouns, I guess–“seem” meaning “things as they seem,” “are,” “things as they are.” So, verbs as noun preceded by ellipses? In any case, they are appropriate here for indicating one constant theme of Stevens’s poetry, usually specifically with the difference between reality and our metaphors for it. On the other hand, “are” is inserted for the rhyme. It should be evident by the fourth line that I could have used fewer words, and sometimes shorter words, to say what I have, but didn’t because I had to have so many syllables per line, and get the meter right. The fourth line should be just “burned to found.” And “found” seems a bit of a strained effort to make a rhyme. Poets don’t “found” poetic worlds so much as “fashion,” “create,” or “form” them. Sometimes such a not-quite right word works beautifully, though–I’m thinking of Blake when he asked “who could frame” the “fearful symmetry of the tyger.

I remember, too, never liking the way “to” followed “too,” but I couldn’t think how elsewise to write that part. Lines 6 and 7 are downright bad due to the padding I’m speaking of “to where the weather’s smallest pieces, earth,/ and earthlife synapsed in the underhue . . .” This ultimately became, “to where the small dirt’s awkward first grey steps/ toward high-hued sensibility begin . . .” which is superior (I believe) though not perfect because all four of the adjectives in first of the two lines adds something to the picture the dirt in spring using seeds to ascend to color (and “sensibility,” which I won’t defend here). Does such padding kill a poem? Not unless overdone, in formal verse, where I believe padding nearly always happens–but pays off in the best poems with in a smooth rhythm and rhyme (and rhyme is a wonderful thing, so what if great poems can eschew it). Does padding kill this poem? I frankly don’t know. Certainly “the fading fragments of the past,” wounds it, not only as padding but as cliche–i.e., fragments of the past are pretty sure to be “fading.”

I don’t remember if the version of this sonnet I consider the final one still “has “windily” in it. I wanted to refer to the brisk weather I thought rule many of Pound’s best poems, but “windily,” alas, also suggests the windy speaker that he too often was.

Finally, there’s the repetition of “How vain they’ve been,” which I confess was due to the need to fill out the line–although one can argue that it helps emphasize the strong feeling of the couplet it’s in. As I’ve said before, however, when I read this poem after not having read it for probably more than ten years, I did like it, not noticing the problems I’ve now found in it. I’m convinced it’s not a mjor poem, but it may not be a bad one.

Incidentally, I’ve not yet mentioned the poem’s subject. It is a simple, conventional one: the desire of a poet to write great poetry–with explicit praise to the side of three poets, and implicit praise of a fourth (Keats). I claim that no poem’s subject is important, unless it’s unclear or ridiculously stupid (e.g, raw toads taste better spread with peanut butter). It’s how the subject is treated that counts. What kind of monument to it does the poem’s words create? Most import for me has always been how well it gets an engagent to Manywhere-at-Once (which is where an effective metaphor takes you, but not only metaphors), how often, how deeply, and how richly. Oh, and archetypal depth is crucial for the best poems. This one has to do with its speaker’s needs for greatness, and that’s are archetypally significant as any subject can be.

I never bothered to mention my poems “melodation,” either. That’s what I call the many ways poems can give auditory pleasure: rhyme, alliteration, assonance, consonance, euphony, even cacophony in the right place; and meter. I claim that even poor poems usually have effective melodation. There’s always the danger of too much of one kind–alliteration, most commonly; and of cliche–in choice of rhymenants (which is what I call words that rhyme), for example, “love/above.” My sonnet avoids cliched rhyming through the use of my bow-rhymes, and I don’t think any of my melodations is overdone. Most of them, by the way, came naturally. I think few people who have composed enough poems think about melodation while making a poem: it just comes. Every once in a while, you may have to think about it when not sure which of two or more words is right for a line–usually one will make the best sense but not sound as well as a second.

Did anyone notice how I ran out of gas toward the end of the above. For a while yesterday I really thought this would turn into a Terrific Example of New Criticism at its Best. Oh, well, I don’t yet think it’s wretched.

.

Entry 823 — A Lesson in Critiquing a Poem

Tuesday, August 7th, 2012

Here’s “Sonnet from my Forties, No. 2,” again:

Much have I ranged the lolli-skied deep art

that Stevens somehow miracled around

his meditations into seem and are,

and each time burned eventually to found

a like domain. I’ve often ventured, too,

to where the weather’s smallest pieces, earth,

and earthlife synapsed in the underhue

of Roethke’s thought and felt no less an urge

to master his techniques, as well. And I’ve

explored the fading fragments of the past

that Pound re-morninged windily alive,

sure I would one day follow on his path.How vain they’ve been, how vain my fantasies:

their only yield so far just lines like these.

I mentioned when I posted it two days ago that it had flaws. Struggling as almost always to find something to do a blog entry on, I thought of how good it would be to use as a lesson on critiquing poetry on. Good because it does have a lot of flaws to point out and comment on. It has a fair number of excellences, too, I must assert. A good critique will mention them, as well. What makes the poems much better than most poems for me to critique is that it’s mine. Hence, I probably know more about it than anybody else who might try to critique it. Much more important, I don’t have to worry that I’ll hurt its author’s feelings if I’m too rough on it: I know he doesn’t have any, and is too much of a jerk for it to matter if he did.

To start with, let me say that his rhyming is among the greatest virtues of his poem. Blockheads, of course, will have already given it thumbs down for having what they consider three near-rhymes. If it did, I would agree with them that they were defects, for my reactionary belief is that every line in a sonnet should rhyme with some other line, fully rhyme. Well, although “are/art,” “earth/urge” and “past/path” are not conventional full rhymes, their rhymnants rhyme as much as conventional rhymnants by the following logic: “are” is as close in sound to “art” and “are” is to “far.” In each case, one syllable is different in over-all sound from the syllable it rhymes with in one sound only, but the same in the other two syllables (and I take all syllables to have three sounds, including the ones which once or twice contain the sound of silence). Those claiming, as many opposed to my idea are, that “are”/”art” is just an alliteration are clearly wrong–as wrong as declaring “are”/”far” just a consonance. To my ear, the new kind of rhyme sounds as pleasantly echoic as the old. I can’t see any reason to disapprove of it than simply the fact that it’s different from received rhymes. Wilfred Owens’s “rim-rhymes,” as I named them many years ago, such as “blade/blood” and “flash/flesh,” which are from his “Arms and the Boy,” seems to have gained some acceptance but few poets are making much use of it. My impression, in fact, is that only poets using Dickinson near-rhymes as full rhymes, are–and I don’t think much of near-rhymes, though I do think some poets have used them quite well. (I always feel Dickinson used them because she couldn’t come up with a real rhyme rather than for some aesthetic reason. I’m not up to researching it, but I wonder if anyone hating what I’ve just said could see if he can find an instance of Dickinson’s using a near-rhyme when a real rhyme would have worked but not been as aesthetically effective?)

I haven’t come up with good names (like “rim-rhyme”) for the two other kinds of full rhymes I accept. One set I like but don’t really believe should be adopted are “chime-rhyme” and “rile-rhyme.” The first is okay although I would claim all three full rhymes chime equally; the second is a bit silly, since I never began using the kind of rhyme it names to rile anyone. My best attempt is “stern-rhyme” for rhymes of syllables sharing the same last two sounds, as “chime” and “rhyme” do; and “bow-rhyme” for rhymes of syllables sharing the same first two sounds, as “rile” and “rhyme” do.

While discussing my bow rhymes, I would critique them as not only not defects but as virtues, since they extend the possibilities of rhyme and are fresh elements of my poems, and freshness is a cardinal need of superior poetry. As long as it doesn’t go too far, as “lolli-skied” may. My intention was to indicate a sky glistening like a lollipop (and as tasty as one!), the way I feel Stevens’s skies, or the equivalent thereof, do. But “lolli” has connotations of juvenility and triviality which may make it inappropriate–although a hint from children’s worlds needn’t be a fault. I dropped this locution from what I considered my best versions of the sonnet–with sorrow. I’m still not sure I was right to.

Most things in any poem are bothersomely right/wrong. My first line, for instance, will sound awkward to moderns, but is an intentional allusion to the opening of Keats’s “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer.” It immediately ignores one requirement of the sonnet-form, its meter’s being iambic. True, all formal verse is allow to break with its proper meter at times: most scholars claim it is necessary to prevent monotony. I don’t agree, especially for so short a poem as the sonnet. In fact, I would scan the first two words of my sonnet as “Much have” rather than “Much have,” for I believe forcing a meter on a formal poem is better than breaking meter. For one thing, it emphasizes another main feature of superior poetry, its not being prose. It also pounds the monotonousness of a poem into the mind of the poem’s engagent sufficiently to provide a counter-irritant to the more extreme breaks with prose expectations, and common sense, which I consider the best use of meter. A monotonous sky and ocean for a ship full of lunatics.

Boink. More to follow–tomorrow, I hope.

.

Entry 821 — “Sonnet from my Forties,” Version 2

Sunday, August 5th, 2012

According to Of Manywhere-of-Once, the second version of the sonnet I worked on from 1983 until just a few weeks ago, if indeed it’s really finished, I wrote the following version of it, my second:

Much have I ranged the lolli-skied deep art

that Stevens somehow miracled around

his meditations into seem and are,

and each time burned eventually to found

a like domain. I’ve often ventured, too,

to where the weather’s smallest pieces, earth,

and earthlife synapsed in the underhue

of Roethke’s thought and felt no less an urge

to master his techniques, as well. And I’ve

explored the fading fragments of the past

that Pound re-morninged windily alive,

sure I would one day follow on his path.How vain they’ve been, how vain my fantasies:

their only yield so far just lines like these.

The reason I being up here is that I just happened to read it after finding a copy of the book and getting it ready to send it to Andrew Topel, who ordered a copy. What’s interesting . . . and sad . . . is that I thought it better than my final version. Looking at it again as I typed it into this entry, I saw a few defects, and noted the omission of Yeats, whom my final version lauds. One of the defects was in the ninth line which had, “to master his and Stevens’ craft.” “Stevens’” should have been “Stevens’s,” which screwed up the meter, so I changed it to what it now is, the only thing I changed. Final thought: that I really have no idea which of the two is better–or–probably–which of the twenty or thirty versions of the thing (possibly many more if I count all ten versions of a given day that differed from one another by half-a-line or less) I eventually made is the best. John Bennett told me I didn’t have a bunch of different versions but a bunch of different sonnets. I wasn’t attracted to the idea then: I wanted to make a perfect sonnet, and chuck all I’d made that weren’t. I now believe he may well have been right.

One would have thought I’d come out of my experience with this sonnet with some facility for the form, but I don’t believe I’ve ever made a sonnet again.

.

Entry 596 — A Final Version of my Sonnet, Again

Saturday, December 17th, 2011

I couldn’t stay way from it. I kept running it through my mind since posting the previous version here a week or two ago, finally coming up with the version below the night of 15 December. Note, each line should be pronounced as an iambic pentameter, including the third.

Sonnet from My Forties

Much have I ranged the kingdoms Stevens forged

Of deeply penetrating inquiries

Into, and deft use of, the metaphor,

And volumes filled in vain attempts to reach

The heights that he did. Often, too, I’ve been

To where the small dirt’s awkward first grey steps

Toward high-hued sensibility begin

In Roethke’s verse, or measured the extent

Of wing-swirled, myth-electric, royal light

That Yeats achieved, or marveled down the worlds

That Pound re-morninged splashingly to life,

But failed as dismally to match their works.

Yet still, nine-tenth insane though it now seems,

I seek those ends; I hold to my huge dreams.

Diary Entry

Friday, 16 December 2011, 11:30 A.M. I have a few small exhibition-bookkeeping chores yet to do that I’m letting go for this weekend so I can concentrate on the stack of reviews for Small Press Review I have to do. One of them will be of I, a novella by Arnold Skemer that I find excellent but a very slow read, in the best sense of the description.

.

Entry 586 — “Sonnet from My Forties”

Wednesday, December 7th, 2011

While hunting this morning for an essay of mine that had something in it I wanted to tell Richard Kostelanetz about, I came across a copy of Jake Berry’s zine, The Experioddicist, and found a version of the sonnet of mine I wrote about in my Of Manywhere-at-Once. I spent months on it, never getting it right, then continued working on it on and off–until now, never getting it right. I often thought for a while I had. That’s the case now. The version in The Experioddicist isn’t quite right, but I immediately saw how I thought I could change it so it was: here’s the once again final version:

Sonnet from My Forties

Much have I ranged the broad-skied latitudes

That Stevens festivalled his inquiries

On truth and the imagination to,

And reams used up in vain attempts to reachThe heights that he did. Often, too, I’ve been

To where the small dirt’s awkward first grey steps

Toward high-hued sensibility begin

In Roethke’s verse, or measured the extentOf wing-swirled, myth-electric, royal light

That Yeats achieved, or marveled down the worlds

That Pound re-morninged windily to life,

but failed as dismally to match their works.Yet still, nine-tenths insane though it now seems,

I seek those ends; I hold to my huge dreams.

Okay, now that I’ve typed it out, I’m not so enthusiastic about it. I changed line 3 from “On truth and metaphor in due course to” to “On truth and the imagination to,” a definite improvement. The first stanza still doesn’t quite do it for me, but the rest of the poem seems fine–or would, I’m sure, if I hadn’t read and reread it some many hundreds of times. Needless to say, it’s in the old-fashioned mode of Hopkins/Yeats/Thomas and probably over-rich–certainly to today’s taste. It’s somewhat redeemed by its use of reversed rhymes (which are full rhymes, not alliterations). It still sums up my life in poetry, though–alas.

* * *

Tuesday, 6 December 2011, 5 P.M. A non-productive day, although I did try to get a few things done. Mainly, I spent a couple of hours getting a copy of terms that are for use in my “Mathemaku for Scott Helmes”–twice, the second time because I needed them a different size. (Actually, I plan to have a full-size version of the work, and a smaller one, so I can use both sets of terms.) Earlier, another round of tennis, which went fairly well for me, for a change. A second breakfast with teammates at the nearby McDonald’s followed. Later I had a doctor’s appointment to get through and some grocery shopping to do. I got some new medicine for my continuing urinary problems. Right now I’m weary, as usual. I feel, as I often do, that if I could just go to bed and go to sleep for twelve or thirteen hours, I’d be a new man. But, although I’m more than sleepy enough than I should need to be to go to sleep, the chances are I wouldn’t be able to get to sleep, nor stay asleep for even as much as an hour if I did.

.

Entry 109 — An Old Sonnet

Wednesday, February 17th, 2010

I was around twenty when I wrote this following sonnet. A few days ago, I changed its last two lines–and, just now, line one’s “eagle eyes” to “sharpened eyes.” I have all kinds of trouble evaluating it. It may be okay or even good, but it’s so much in a long-disused style, in spite of its backwards rhyming that halfwits won’t consider rhyming, that I can’t read it with much enjoyment.

John Keats

He read of Greece; and then with sharpened eyes,

espied its gods’ dim conjurations still

in breeze-soft force throughout his native isle–

in force in clouds’ remote allusiveness,

in oceanwaves’ eternal whispering,

in woodlands’ shadowy impermanence.

Once cognizant of earth’s allure, he sought

a method of imprisonment – a skill

with which to hold forever what he saw.

The way the soil and vernal rain converge

in carefree swarming flowers, Keats & Spring

then intersected quietly in verse.

The realms he had so often visited

at once grew larger by at least a tenth.