Entry 444 — My Latest Pop-Off

May 20th, 2011

In case the morons at Poetry don’t post my pop-off, and they haven’t yet, here is approximately what I said (unfortunately, I failed to keep a copy):

Why should anyone care what one third-rate knownstream critic has to say in praise of poetry that has been acadominant for over twenty years now (although only recently noticed by Poetry Magazine), so-called “language poetry” (which is just collections of non sequiturs with none of the significant focus on the aesthetic uses of grammar that real language poetry has) compared with what another third-rate knownstream critic has to say in praise of the kinds of poetry established long before that when there’s innovative poetry extant to explore far from the tired interests of such critics–and Poetry Magazine.

Hmmm, I think I improved it. I definitely made it nastier, out of annoyance for Poetry’s not posting it. I now think it would have been interesting to have added a challenge to Poetry and its readers to visit my infraverbal mathematical poems at Tip of the Knife or my mathematical poems at the Otherstream Unlimited Blog and tell me why they, and poems like them, don’t deserve recognition. My poems rather than anyone else’s because I feel I can argue more knowledgeably for them against the Philistines than I can for any others. But also because of my growing egocentric need to yowl for me!

Later note: my comment was posted. It was followed by a comment consisting almost entirely of a quotation of Adorno which seemed to me nothing but meaningless subjective gush.

Entry 443 — I’m Still Here

May 19th, 2011

Just a little news bulletin to let people know I’m still around.

1. I’m scheduled for hip replacement surgery 1 June.

2. I just popped off at the Poetry magazine site against a review of recent books by Marjorie Perloff and Reginald Shepherd, Unorginal Genius and A Martian Muse, ” which–according to Robert Archabeau, Poetry’s fatuous reviewer– “have wonderful moments, and at their best each shows us a remarkable critical mind at work.” I aired my usual gripe, that the Establishment is ignoring my kind of poetry. I seem to have a need to do this every month or so–to become at least a smudge on the Surface of American Culture. I can’t simply ignore it.

Entry 442 — Contemporary Poetry

May 15th, 2011

Poetry Between 1960 and 2010

Wilshberia, the continuum of contemporary poetry composed

between around 1960 and the present certified by the poetry

establishment (i.e., universities, grants-bestowing organizations,

visible critics, venues like the New Yorker and the American

Poetry Review) begins with formal poetry like much of Richard

Wilbur’s work. Descent into a different lesser formality of neo-

psalmic poetry based on Whitman that Ginsberg was the most

well-known recent author of, next comes free verse that is

nonetheless highly bound to implicit rules, Iowa Plaintext Poetry;

slightly further from traditional poetry the nearprose of Williams

and his many followers who seem to try to write poetry as close to

prose as possible. To this point, the poetry is convergent,

attempting to cohere around a unifying principle. It edges away

from that more and more as we continue over the continuum,

starting with surrealist poetry, which diverges from the world as we

know it into perceptual disruption. A bit more divergent is the

jump-cut poetry of the New York School, represented at its most

divergent by John Ashbery’s most divergent poems and the jump-

cut poetry of the so-called “language poets,’ which is not, for me,

truly language poetry because grammatical concerns are not to

much of an extent the basis of it

The Establishment’s view of the relationship of all other poetry

being composed during this time to the poetry of Wilshberia has

been neatly voiced by Professor David Graham. Professor Graham

likens it to the equivalent of the relationship to genuine baseball of

“two guys in Havre, Montana who like to kick a deer skull back &

forth and call it ‘baseball.’ Sure, there’s no bat, ball, gloves,

diamond, fans, pitcher, or catcher– but they do call it baseball, and

wonder why the mainstream media consistently fails to mention

their game.” Odd how there are always professors unable to learn

from history how bad deriding innovative enterprises almost

always makes you look bad. On the other hand, if their opposition

is as effective as the gatekeepers limiting the visibility of

contemporary poetry between around 1960 and 2000 to Wilshberia

has been, they won’t be around to see that opposition break down.

Unfortunately, the innovators whose work they opposed won’t be,

either.

Not that all the poets whose work makes up “the Underwilsh,” as I

call the uncertified work from the middle of the last century until

now, are innovative. In fact, very few are. But the most important

poetries of the Underwilsh were innovative at some point during

the reign of Wilshberian poetry. Probably only animated visual

poetry, cyber poetry, mathematical poetry and cryptographic poetry

are seriously that now. It would seem that recognition of

innovative art takes a generation

The poetry of the Underwilsh at its left end has always been

conventional. It begins with what is unquestionable the most

popular poetry in America, doggerel–which, for me, it poetry

intentionally employing no poetic device but rhyme; next come

classical American haiku–the 5/7/5 kind, other varieties of haiku

being scattered throughout most other kinds of poetry–followed by

light verse (both known to academia but looked down on); next

comes contragenteel poetry, which is basically the nearprose of

Williams and his followers except using coarser language (and

concerning less polite subjects, although subject matter is not what

I look at to place poetries into this scheme of mine); performance

poetry, hypertextual poetry; genuine language poetry;

cryptographic poetry; cyber poetry; mathematical poetry; visual

poetry (both static and animated visual poetry) and sound poetry,

with the latter two fading into what is called asemic poetry, which

is either visimagery (visual art) or music employing text or

supposed by its creator to suggest textuality and thus not by my

standards kinds of poetry, but considered such by others, so proper

to mention here.

Almost all the poetries in the Underwilsh will eventually be

certified by the academy and the rest of the poetry establishment.

The only interesting questions left will be what kind of effective

poetry will then be ignored, and whether or not the newest poets to

be certified will treat what comes after their kind of poetry as

unsympathetically as theirs was treated.

Entry 441 — Vocational Resume

May 10th, 2011

| First Name: | Bob |

| Last Name: | Grumman |

| Suffix: | |

| Nationality: | American |

| Full Birth Date (MMDDYYYY) or Year Only: | 02021941 |

| City of Birth: | Norwalk |

| State of Birth: | [USA] Connecticut |

| Country of Birth: | United States |

| Sex: | M |

| Email: | [email protected] |

|

|

|

| Career: | Datagraphic Computer Services, computer operator, 1971-76; Charlotte County School Board, substitute teacher, 1994-2009. Writer. |

| Publications: | Poems (visual haiku), 1966; Preliminary Rough Draft of a Total Psychology (theoretical psychology), 1967; A Straynge Book (children’s book), 1987; An April Poem (visual poetry), 1989; Spring Poem No. 3,719,242 (visual poetry), 1990; Of Manywhere-at-Once, vol. I (memoir/criticism), 1990; Mathemaku 1-5 (mathematical poetry), 1992; Mathemaku 6-12 (mathematical poetry), 1994; Of Poem (solitextual poetry), 1994; Mathemaku 13-19 (mathematical poetry), 1996; A Selection of Visual Poems (visual poetry), 1998; min. kolt., matemakuk, 2000; Cryptographiku 1-5 (cryptographic poetry), 2003; Excerpts from Poem’s Search for Meaning (solitextual poetry), 2004; Greatest Hits of Bob Grumman (mixture of poetries), 2006; Shakespeare and the Rigidniks (theoretical psychology), 2006; From Haiku To Lyriku, 2007; April to the Power of the Quantity Pythagoras Times Now (collection of mathemaku), 2007: This Is Visual Poetry (visual Poetry), 2010; Poem Demerging (solitextual poetry), 2010. A Preliminary Taxonomy of Poetry, 2011. EDITOR: (with C. Hill) Vispo auf Deutsch, 1995; Writing to Be Seen, vol. I, 2001. |

| Home Address | 1708 Hayworth Rd. |

| City Home: | Port Charlotte |

| State Home: | [USA] Florida |

| Country Home: | United States |

| Zip Code Home: | 33952 |

| Phone Home: | (941) 629-8045 |

| Business Address | PO Box 495597 |

| City Business: | Port Charlotte |

| State Business: | [USA] Florida |

| Country Business: | United States |

| Zip Code Business: | 33949 |

| Phone Business: | (941) 629-8045 |

| Subject Code1: | PLAYS/S C R E E N PLAYS |

| Subject Code2: | POETRY |

| Subject Code3: | PSYCHOLOGY |

| Subject Code4: | LITERARY CRITICISM AND HISTORY |

| Subject Code5: | SCIENCE FICTION/FANTASY |

| Subject Code6: | NOVELS |

Entry 440 — Support for My Hyperneologization

May 7th, 2011

.

I came across it by chance:

APODIZATION* literally means “removing the foot”. It is the

technical term for changing the shape of a mathematical function, an

electrical signal, an optical transmission or a mechanical structure.

An example of apodization is the use of the Hann window in the Fast

Fourier transform analyzer to smooth the discontinuities at the

beginning and end of the sampled time record.

Now, then, is this a pompous, unpronounceable, superfluous term? It was once a coinage, you know. Why not “foot-removal?” I suspect because whoever coined it wanted it quickly to narrow the mind into mathematics, i.e., a particular system or discipline–which I also want most of my terms though not “Wilshberia” to do. I know: there’s a difference between a certified subject like mathematics and the theoretical psychology I try to link my terms to. I understandably (I should think) don’t consider that relevant. Why should someone be discouraged from systematic naming of terms to fit interactingly into a theory he’s creating just because he’s a crank.

I think one reason for my lack of recognition is that the sort of people who might be in sympathy with my hyperneologization are not generally the sort of people with an interest in poetics. As I’ve often declared, I may well be too much of an abstract thinker to be a poet and too much of an intuitive thinker to be a scientist. You’d think that would help me with both groups but it does the opposite. About the only “real” mathematician who appreciates my mathematical poems is JoAnne Growney.

The other day, after my “anthrocentricity’ and “verosophy” had been subjected to the usual reactionary jibes, I asked why “egocentricity” was an acceptable word for “self-centeredness,” but “anthrocentricity” not an acceptable word for “people-centeredness.” Needless to say, no one answered me.

Far too many many academics are so locked into their received understandings that they are blind to how those understandings might be revised or extended in ways that require the coinage of new terms.

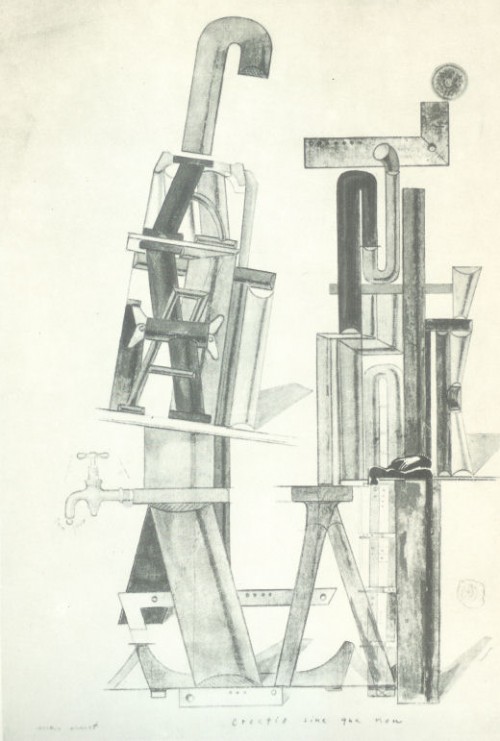

Entry 439 — A Textual Design by Max Ernst

May 5th, 2011

.

This is Erectio sine qua non, by Max Ernst, 1919. I copied it out of Surrealst Drawings, with text by Frantisek Smejkal. I view it as letters taking shape, with other forms, to eventually result in an erection that can be taken to be “meaning” formed of language. Other interpretations of equal validity can be made. Although I made out two words under the faucet, they seem to me much to minor to make this pice a visual poem. Nor, of course, does the book it’s in call it that. Remember, kids, as Uncle Bob keeps telling you, a word should always mean something, but it should always indicate something that it isn’t, or it’s useless. So, if you want to call this neato visimage a visual poem, fine–but Uncle Bob, and maybe one or two other people, will want to know what isn’t a visual poem.

Entry 438 — Fun with the Nullinguists

May 5th, 2011

And just one more language note, since we are poets and poetry readers. . .

Unlike many academics, bureaucrats, or military officials, I don’t think it’s necessary to invent pompous, unpronounceable and superfluous synonyms for simple terms that already exist. At best it’s comic relief. At worst, well, see George Orwell. . . . About the only one of good old Bob’s prolific stream of coinages that strikes me as worth keeping is “burstnorm.” That actually does improve on the other available words, seems to me, and has the advantage of simplicity and poetic power.

–David Graham

Okay, David, tell me what’s wrong with “infraverbal poetry”

–Bob

A guess, “Bob” (& I didn’t even take any pills!) –

M: rigid, defensive tribal and national identities, ungiving hierarchical principles, concentrated authority, reflexive aggression in a repetition compulsion that overrides desires for peace …

–Amy King

Thanks, Amy. It’s good for my morale to know you can’t find anything of consequence wrong with my term.

But this may be a fate not worse than the memento mori of the progeny of Aristotelian logic which remain eternally fixed in delusions of universal absolutes and therefore empty of useful meaning. To wit, Wittgenstein’s remark, “But in fact all propositions of logic say the same thing, to wit nothing…”

–Amy King

Spoken like a true absolutist. Nothing to do with me, though, for I believe in maxilutism, the belief that while no absolutes exist (except in logic and mathematics, I now realize), many maxilutes, or understandings close enough to absolutely true to be treated as absolutes, do exist.

–Bob

* * * * * * *

This kind of nullinguistics is not entirely worthless: when Professor Graham later said “misspelled poetry” was what “infraverbal poetry” should be called, it made me say why he was wrong: “‘Misspelled poetry’ clearly doesn’t work. For one thing it does not indicate whether the misspelling is intended or not. Another is that ‘misspelledly’ doesn’t work very well (I don’t think) as an adverb. Probably most important, there are many examples of infraverbal poems that have much more going on inside them than what most people would think of as misspellings–a letter on its side, for instance. Actually, some infraverbal words are correctly spelled. ‘Misspelling,’ for instance–which I just made up and is certainly not much of an infraverbal poem but is one.” I count the realization that infraverbal words can be correctly spelled a nice addition to my knowledge of them.

Entry 437 — Another New-Poetry Post of Mine

May 4th, 2011

As my day began and through most of it, I was my usual sleepy self. Had a busy doctor-day, too. But I took a couple of APCs three hours or so ago for a headache, and feel quite good. I’m not up to writing a really good entry here, but wrote a pretty funny e.mail to New-Poetry an hour or so after taking the APCs and think it’ll work reasonably well for today’s entry. Here it is as written except that I deleted one word that I’d replaced with a second word but forgot to take out:

>> On 5/4/2011 2:35 PM, Halvard Johnson wrote:

>> Truth-seeking and mindless nihilism are false alternatives, Bob.

>> See what I mean?Get me in a formal debate, Hal, and I’ll plead guilty to any false dichotomies I commit. This one is what I’d call a colloquial one, or maybe an ellipsis–meaning, “truth seeking and sufficient mindless nihilism to prevent truth from being found,” to a verosopher but not to one trying to win an argument. It’s like the statement, “a person is either black or white.” Everyone knows what it means although everyone is also aware that in a small minority of cases it’ll be very hard to decide which a person is. “A person is either black or white” really means “A person either has dark enough skin to be considered by most people to be black or he doesn’t, in which case he is deemed to be white.” Everyone is also aware that “everyone” really means “almost everyone” and that “black” and “white” don’t mean “black” and “white.”

I just realized that what I’ve been writing, slightly changed, would make a good Arthur Vogelsang poem. What a name he has for a poet! If I have the German right. I would be amazed if he is not a favorite of yours, Hal. I was unfamiliar with his work until I got a copy of his Expedition to review for Small Press Review. Very funny. He would take what I said and change the order, and add non sequiturs. Into it surrealize a smoking chimney some woman leans against with her tenses awry and nothing to do with Santa Claus except eye-color, although the latter has to do with chimneys (Santa Clause, not eye-color), if not compulsively since what’s once every 365 or 366 nights a year? Am I what I am because I’m trying to desatirize his work or is he what he is because he is satirizing my verosophy. Which he would agree would be simple to do although he doesn’t know me any more than he knows Santa Claus. Who has nothing to do with sentence structure. Which is nonetheless considered important in some circles. By everyone, which is not to say “everyone.” In most circles. Repetition is important.

Back to Me:

It’s simple. I asked Anny whose side Freddy would be on, mine or Amy’s. The extremely strong implication of that is that Freddy could be expected to be on one side or the other–if we ignore, as we do colloquially (see my preceding paragraph), the possibility that he will be neutral, and my Freddy would never be neutral. Hence, your saying Freddy Laker was the Freddy I meant indicates that you thought Freddy Laker could be expected to be on one side or the other. But you won’t say what it was about him that would cause him to side with either Amy or me.

Sure, you could be having fun with the idea of Freddy Laker’s being on Amy’s side because they are both high fliers, or deliver the goods, etc. Or a knight would be on the side of a King. But I think that after you realized where I was (seeking a truth, remember, although a small one), you would out of considerateness have told me that you were a lot less than as serious about your Freddy as I about mine. True, I was using my Freddy in an attempt at a joke, but a joke in which what my Freddy was, had to be taken seriously for it to work.

Right, I’m going on and on. I am crazy, for I really think there are some out there who will enjoy reading this as much as I’m enjoying writing it (due primarily to the two APC’s I took a while ago for a headache, no doubt). But I’m also writing for myself. I’m going to use this as my blog entry for today. I thought for a moment I’d spare New-Poetry participants from having to see it, and just provide a link to my blog here. Then I thought, why? All someone this offends need do to get me to stop making such posts is to go public with a legitimate case against its value. That means more than denouncing it and/or monster-me. Defeated by a rational case, I would retire from the field. I would hope. Dumped on for being out of tune with Proper Understanding of What’s Right, I fear, won’t have much of an effect on me.

Since few here will take the time for that, maybe Finnegan can add a like and a don’t like button to every post–or be even more insipid and just add a like button as Facebook does.

Why is “egocentricity” a good word and “anthrocentricity” comically stupid a word?

Whee.

–Bob

Entry 436 — Visual Poetry Intro 1a

May 3rd, 2011

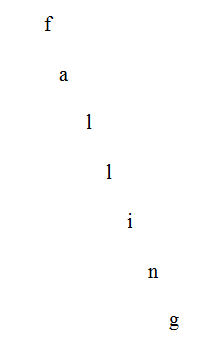

According to Billy Collins, E. E. Cummings is, in large part, responsible for the multitude of k-12 poems about leaves or snow

But, guess what, involvement in visual poetry has to begin somewhere. Beyond that, this particular somewhere, properly appreciated, is a wonderful where to begin at. Just consider what is going on when a child first encounters, or–better–makes this poem: suddenly his mindflow splits in two, one half continuing to read, the other watching what he’s reading descend. For a short while he is thus simultaneously in two parts of his brain, his reading center and visual awareness. That is, the simple falling letters have put him in the Manywhere-at-Once I claim is the most valuable thing a poem can take one to.

To a jaundiced adult who no longer remembers the thrill letters doing something visual can be, as he no longer remembers the thrill the first rhymes he heard were, that may not mean much. But to those lucky enough to have been able to use the experience as a basis for eventually appreciating adult visual poetry, it’s a different story. Some of those who haven’t may never be able to, for it would appear that some people can’t experience anything in two parts of their brains at once, just as there are people like me who lack the taste buds required to appreciate different varieties of wine. I’m sure there are others who have never enjoyed visual poetry simply because they’ve never made any effort to. It is those this essay is aimed at, with the hope it will change their minds about the art.

I need to add, I suppose, that my notion that a person encountering a successful visual poem will end up in two significantly separate portions of his brain is only my theory. It may well be that it could be tested if the scanning technology is sophisticated enough–and the technicians doing the testing know enough about visual poetry to use the right poems, and the subjects haven’t become immune to the visual effects of the poems due to having seen them too often. Certainly, eventually my theory will be testable.

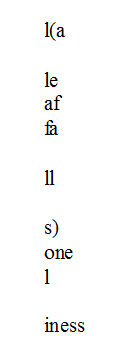

The following poem by Cummings, which is a famous variation on the falling letters device, should help them:

But Cummings uses the device much more subtly and complicatedly– one reads it slowly, back and forth as well as down, without comprehending it at once. Cummings doesn’t just show us the leaf, either, he uses it to portray loneliness. For later reading/watchings we have the fun of the three versions of one-ness at the end and the af/fa flip earlier–after the one that starts the poem.

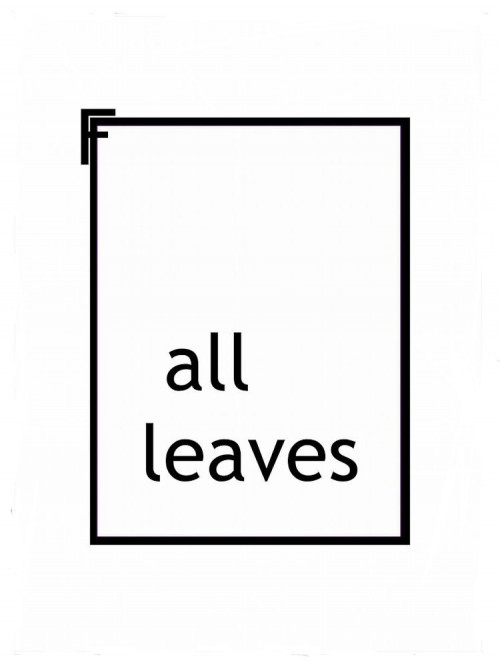

Marton Koppany returns to the same simple falling leaf idea but makes it new with:

In this poem the F suggests to me a tree thrust almost entirely out of Significant Reality, which has become “all leaves”–framed, I might add, to emphasize the point. So: as soon as we begin reading, our reading becomes a viewing of a frame followed quickly by the sight of the path now fallen leaves have taken simultaneously with our resumed reading of the text. Which ends with a wondrous conceptual indication of “the all” that those leaves archetypally are in the life of the earth, and in our own lives. And that the tree, their mother and relinquisher, has been. Finally, it is evident that we are witnessing that ” all” in the process of leaving . . . to empty the world. In short, the archetypal magnitude of one of the four seasons has been captured with almost maximal succinctness.

So endeth lesson number one in this lecture on Why Visual Poetry is a Good Thing.

Note: I need to add, I suppose, that my notion that a person encountering a successful visual poem will end up in two significantly separate portions of his brain is only my theory. It may well be that it could be tested if the brain- scanning technology is sophisticated enough–and the technicians doing the testing use the right poems, and the subjects haven’t become immune to the visual effects of the poems due to having seen them too often. Certainly, eventually my theory will be testable.

Entry 435 — The A/V Ratio

May 2nd, 2011

I’m not sure whether I’m back or not, but I’m working on an entry I believe will be one of my Valuable ones, and just made a post to New-Poetry I thought interesting enough to post the following version of here:

Certain attempts at New-Poetry to explain why I post such disagreeable opinions at times inspired a thought: that everyone varies in the anthrocentricity/verosophy ratio of what he says and writes. By this I mean that we all write with at least some aim of producing a certain reaction in others AND with at least some aim of expressing some truth as we see it, without regard for others’ reactions (except their versophical ones). Those whose usual a/v ratio is, say, 80/20 will tend to think that those like me, whose usual a/v ratio is the opposite, speak and write to elicit reactions from others when in fact all we’re doing is saying what we think as exactly as possible (true, without making too many enemies).

I further think that many people, perhaps the majority of people, are incapable of predominantly versosophical thought, and thus have difficulty recognizing it in others. I would add that an reasonably intelligent person’s a/v ratio will change, sometimes a great deal, depending on the situation.