Entry 434 — More Time Off

April 26th, 2011

.

I’ve decided I need more time off from my blog. I seem to have less than zero energy, at least for any kind of productive writing or other art-making. Could be gone a week or more, who knows.

Entry 433 — Graham vs. Grumman, Part 99999

April 25th, 2011

It started with David Graham posting the following poem to New-Poetry:

. Mingus at The Showplace

.

. I was miserable, of course, for I was seventeen,

. and so I swung into action and wrote a poem,

. and it was miserable, for that was how I thought

. poetry worked: you digested experience and shat

. literature. It was 1960 at The Showplace, long since

. defunct, on West 4th St., and I sat at the bar,

. casting beer money from a thin reel of ones,

. the kid in the city, big ears like a puppy.

. And I knew Mingus was a genius. I knew two

. other things, but as it happened they were wrong.

. So I made him look at the poem.

. “There’s a lot of that going around,” he said,

. and Sweet Baby Jesus he was right. He glowered

. at me but he didn’t look as if he thought

. bad poems were dangerous, the way some poets do.

. If they were baseball executives they’d plot

. to destroy sandlots everywhere so that the game

. could be saved from children. Of course later

. that night he fired his pianist in mid-number

. and flurried him from the stand.

. “We’ve suffered a diminuendo in personnel,”

. he explained, and the band played on.

.

. William Matthews

. Time & Money

. Houghton Mifflin Company

.

I Liked it for the same reasons I like many of Charles Bukowski’s poems, so I said, “Good poem. Makes me wonder if he was influenced or influenced Bukowski. Seems like something by Bukowski, Wilshberianized.”

Mike Snider responded that “Matthews was a far better poet than Bukowski thought himself to be, and he did indeed know his jazz. At the other end of some cultural curve, I love his translations of Horace and Martial.

“And I love your work, Bob, but ‘Wilshberia’ is getting quite a bit past annoying.”

I may be unique among Internetters in that when I post something and someone (other than a troll) responds to it, I almost always carry on the discussion. I did that here: “I think Bukowski at his rawest best was equal to Matthews, but extremely uneven. One of his poems about a poetry reading has the same charge for me that this one of Matthews’s has. I haven’t read enough Mattews to know, but suspect he wrote more good poems than Bukowski did.

“(As for my use of ‘Wilshberia,” I’m sorry, Mike, but it can’t be more annoying to you than Finnegan’s constant announcements of prizes to those who never work outside Wilshberia are to those of us who do our best work outside of it, prizelessly. Also, I contend that it is a useful, accurate term. And descriptive, not derogatory.”

At this point David Graham took over for Mike with some one of his charateristics attempts at wit: “Sorry, Mike, but I have to agree with Bob here. Just as he says, ‘Wilshberia’ is a useful, accurate term, in that it allows someone to see little important difference between the work of Charles Bukowski and William Matthews.

“Think how handy to have such a term in your critical vocabulary. Consider the time saved. Sandburg and Auden: pretty much the same. Shakespeare and Marlowe: no big diff. Frost and Stevens: who could ever tell them apart?

“It’s like you were an entomologist, and classified all insects into a) Dryococelus australis (The Lord Howe Stick Insect) and b) other bugs.”

Professor Graham is always most wittily condescending when he’s sure he has ninety percent of the audience behind him, which was sure to be the case here.

Needless to say, I fired back: “Seeing a similarity between those two is different from seeing “little important difference between” them, as even an academic should be able to understand.

“Wilshberia, for those who can read, describes a continuum of poetry ranging from very formal poetry to the kind of jump-cut free association of the poetry of Ashbery. The sole thing the poets producing the poetry on it have in common is certification by academics.

“No, David, (it’s not like being an entomologist who “classified all insects into a} Dryococelus australis [The Lord Howe Stick Insect] and b} other bugs). Because visual poetry, sound poetry, performance poetry, cyber poetry, mathematical poetry, cryptographic poetry, infraverbal poetry, light verse, contragenteel poetry, haiku (except when a side-product of a certified poet) and no doubt others I’m not aware of or that have slipped my mind are meaninglessly unimportant to academics as dead to what poems can do that wasn’t widely done fifty or more years ago as you does not mean they are the equivalent on a continuum of possible poetries to a Lord Howe Stick Insect in a continuum of possible insects.” Then I thanked the professor for “another demonstration of the academic position.”

My opponent wasn’t through: “A rather nice nutshell of my oft-expressed reservation about Bob’s critical habits above. Note how in his definition of Wilshberia above, ‘the sole thing’ that characterizes such poetry is ‘certification by academics.’ I think we all know what ‘sole’ means. OK, then, it has nothing whatsoever to do, say, with technical concerns. There is no meaningful aesthetic distinction involved. And thus it is obviously not definable according to whether it is breaking new technical ground, because “the sole thing” that defines it is whether academics ‘certify’ it, whatever that means. And as we well know, academics tend to appreciate a spectrum of verse, from the traditional forms and themes of a Wilbur to the fragmentation and opacity of various poets in the language-centered realm.

“But look at the second paragraph above. What are academics being accused of? Oh, it seems we don’t appreciate poetry that breaks new technical ground or challenges our aesthetics. We don’t like poetry of various aesthetic stripes recognized as important by Bob.

“Whether or not that accusation is even true (another argument), does anyone else see a certain logical problem here?”

I didn’t say much. Only that he was wrong that “There is no meaningful aesthetic distinction involved” involved in my characterization of Wilshberia because aesthetic distinctions are involved to the degree that they affect academic certifiability, which they must–as must whether the poetry of Wilshberia is breaking new technical ground.

I proceeded to say, “The meaning of academic certification should be self-evident. It is anything professors do to indicate to the media and commercial publishers and grants-bestowers that certain poems are of cultural value. Certification is awarded (indirectly) by teaching certain poems and poets–and not others; writing essays and books on certain poems and poets–and not others; paying certain poets and not others to give readings or presentations at their universities; and so forth. What (the great majority of) academics have been certifying in this way for fifty years or more is the poetry of Wilshberia.” “Only,” I would now add.

I also noted that I had I previously defined Wilshberia solely as academically certified poetry. “Implicitly, though,” I claimed, “I also defined it as poetry ranging in technique from Wilbur’s to Ashbery’s. Since that apparently wasn’t clear, let me redefine Wilshberia as “a continuum of that poetry ranging from very formal poetry to the kind of jump-cut free association of the poetry of Ashbery which the academy has certified (in the many ways the academy does that, i.e., by exclusively teaching it, exclusively writing about it, etc.”

Oh, and I disagreed that ” . . . as we well know, academics tend to appreciate a spectrum of verse, from the traditional forms and themes of a Wilbur to the fragmentation and opacity of various poets in the language-centered realm.”

“My claim,” Said I, “remains that the vast majority of them think when they say they like all kinds of poets from Wilbur to Ashbery that they appreciate all significant forms of poetry. I have previously named many of the kinds they are barely aware of, if that.”

That was enough for the professor. He retired to an exchange with New-Poetry’s nullospher, Halvard Johnson, about not having a certificate indicating he was a poet in good standing.

Entry 432 — 3 Lunberry Jars

April 24th, 2011

Entry 431 — More on the Lunberry Installation

April 23rd, 2011

.

When I visited Clark’s installation, I somehow failed to notice that he had three texts, not just one, in water-filled jars in the three-part lobby showcase–because, I guess, two were in colored water. In one respect, I was lucky: at the time, the one I saw, the central one, may have been at its best state of decomposition, for I found it enchantingly like a jut-filled, twisty opening in a secret caves. Here, according to Clark, is a more accurate description of the trio of showcases:

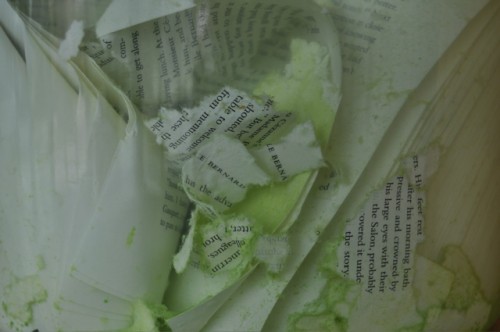

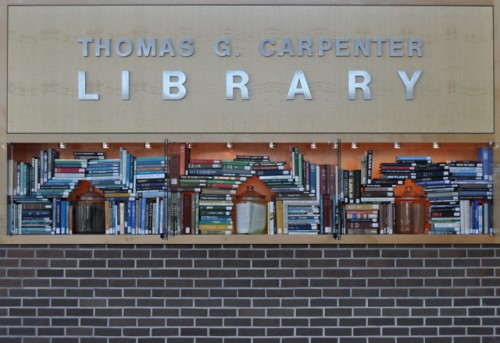

The showcases were divided into three sections, mirroring the stairway (and, of course, something or other outside the library)—water, trees, sky—with each section filled with books selected because that key word happened to be in its title. The selection of books was, as a result, wildly eclectic, linked only by that one word. The water section had, immersed within it, Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams; the trees section had The Selected Writings of Paul Cézanne; and the sky section had André Breton’s surrealist classic Nadja.

Of the three, Cézanne’s writings degraded the most dramatically over the four weeks of their immersion and, by the final week, had taken on something of the geologic look of Cézanne much-painted mountain, Mt. Ste. Victoire. The quality of paper, etc. must have contributed to that.

For the most part, I left the books alone to degrade at their own pace (I’d added color-appropriate water colors to each jar), but a couple of times I got into the jars and shook them up a bit, accelerating the decay (and the variety of pages visible). By the end, the books were, in fact, stinking to high heaven; removing the jars was a disgusting experience, especially the Cézanne; it smelled like a rotting carcass!

.

Entry 430 — Re: Clark Lunberry’s UNF Installation

April 22nd, 2011

.

Go here to see a slide show about it, which will give you a much better idea of the adventure it was–the evolving adventure–than my entries on it.

Entry 429 — Some Grumman Logic

April 21st, 2011

The sentence below this one is false.

The sentence above this one is true.

What can we now say about the two sentences above? That, if we dispense with the false true/false dichotomy, neither is either true or false: each is true/false or paradoxical. Parodoxes are inevitable in any human language, which in my thinking includes the language of mathematics and all the sciences. It seems to me they never occur in nature. That is, nothing in reality except our attempts to describe is ever paradoxical. Hence, two parallel lines can meet each other in Non-Euclidean geometry, but not in the real world.

An aside: I’ve always wondered at the fact that many intelligent people with scientific backgrounds find the idea that parallel lines that meet will exist if the universe were the surface of a sphere. Only in geometry. In the real world nothing that has less spatial dimensions than two can exist. Start drawing a line on your universe as the surface of a sphere and your first tiny dot with burst out if it on both sides.

Related to this absurdity is the idea of curved space. But that’s just an absurdity of expression–saying, for instance, that a curving ray of light curves due to the effect on space of gravity rather than due to the effect of gravity on it.

It applies, too, to the idea of transfinite numbers. The idea behind that, according to George Gamow is that you can’t form a list of infinitely-repeating decimal fractions that contains them all as shown by the fact (and this is true) that if someone brings up a fraction he claims is not on your list, giving you the first ten digits, say, and you show him it is on your list, he can show it isn’t by showing you the eleventh digit on his is different the eleventh digit on yours, or–in the one in ten chance thatthe digits match, that some other later digit on his fraction is different from the one in that spot on yours.

But that procedure can work oppositely: you can make a list of all possible decimal fractions including infinitely-repeating ones and challenge him to find an infinitely-repeating decimal fraction of a given length that’s not on your list. If you take all the integers in order, reversed, and make them infinitely-repeating decimal fractions by putting a point in front of each one as here:

.1 .2 . . . .9 .01 .11 .21 . . . .91 .02 . . . .99 .001 . . .

he will not be able to give you any decimal that you can’t immediately indicate the location of on your list of a decimal fraction matching whatever string of digits he gives you. Say it’s 00958746537 . . . That will be the 73564785900th number on your list. He can’t then say his number’s twelfth digit is different from your number’s because you can honestly say you don’t know what your number’s twelfth digit is. But that his second number can be as easily found as his first.

So you have two true statements about mathematics that contradict each other. I say they are therefore true/false statements, or paradoxes.

I don’t believe any real object can be infinite. Space may be said to be, but it doesn’t exist, in my philosophy. But I doubt that there’s any way of testing the truth of what is just my opinion.

Note to anyone concerned about my health: I managed to get through a stress test yesterday without having a heart attack or stroke. I’m now wearing a heart monitor that will come off in three hours, at ten a.m. I felt peculiar a few times while wearing it. I hope they don’t turn up as problems on the monitor’s record.

I had trouble walking properly on the stress test treadmill. My doctor and the woman overseeing me got quite frustrated. I felt incredibly stupid. I think I know what happened: there are rails to hold onto that I couldn’t grip without slightly stooping because I’m tall but have the arm-length of a 5′ 9″ white man, so I felt very awkward–until I just let my fingers touch the rails. I also tried too hard because I thought I was going to be tested with stress. When it was over, I asked why they’d never speeded it up. No stress at all except the stress of feeling physically incompetent.

Hmmm, my spell-checker doesn’t like “speeded up.” But surely “sped up” is not correct. Weird. I’d automatically say, “I sped home,” not “I speeded home.” But that’s great. The language should be crazy–as long as it tries for maximal stability.

I have opined on occasion that people who can remember rules of usage like sped/speeded may be use them to show their superiority to those who can’t–in other words, the lay/lie distinction that I hold to, for example, I hold to partly to show I’m not low-class. But I hope my main reason is that I like ways to break out of universal rules as a literary artist. I do believe in social classes, though. It slightly simplifies relating to people, which is incredibly complex. Not that my believing in it matters since a classless society is impossible.

Entry 428 — My Heart Monitor

April 20th, 2011

.

Today I’m wearing a heart monitor. I took a stress test earlier. Now my main concern is not doing anything that will unstick the electrode patches or whatever they are that have me stuck to the monitor in five different places. All this is the make sure I can withstand the hip replacement surgery I’ve put in for. It seems to me a good excuse to take the rest of the day off, so this is all I’m posting here today.

Entry 427 — Math in the Work of Kedro

April 19th, 2011

Entry 426 — A New Chapbook by Beining

April 18th, 2011

There are a fair number of excellent visual poets who are excellent linguexpressive poets, as well: Karl Kempton, Sheila Murphy, Geof Huth, Crag Hill, to mention just a few. Another is Guy R. Beining, who is also a wonderful pure visimagist (i.e., maker of visual art), as my top image of his painting for the cover of nozzle 1 – 36, his recent collection of linguexpressive poems, proves. Following it are two of the poems in the book. As I always wonder, as practically the only one who has discussed his work (too seldom I fear, and too worn out to do so here), why he is not better known.

Entry 425 — Lunberry Installation, Part 3

April 17th, 2011

Finally I’m returning to Clark Lunberry’s installation. Ironically, I already had the words I’m posting written–they’re all from the diary entry I made when I got home from Jacksonville, although somewhat revised:

So, we spent time at a Farmers’ Market–part of it very very pleasantly, under a freeway underpass on a bank of the river through Jacksonville, the name of which I now forget. We had lunch there, while listening to a girl singer accompanied by guitar–in the folk vein, I guess, and nice. Then quite a distance to the college Clark teaches at to see his installation (as well as an excellent exhibition of some of Marton’s pieces) . I wasn’t prepared for the outdoor part of the installation, “SENSATION” making an X with “THINKING” floating in the center of a small pond with geese swimming in it in front of where we parked. An evolving installation: later Clark rowed out to the X in a kayak and changed “THINKING” to “INKING.” It seemed okay to me. The words are from a quotation from Cezanne he’s done many variations on at other installations of this particular (4-year) installation.

The installation continued in the library building next to the pond. First, the long glassed-in exhibition space in the library’s lobby I had a picture of a few entries ago. In it were a huge number of books on water, trees and sky, plus an intriguing mush of torn pages of text in the jar that summed up the adventure into a secret cave that all the books contained. Then three visual poems, each taking up one portion of the stairway window, or glass wall, that faced the pond. The first featured repetitions of the word, “WATER,” the second “TREES, the third “SKY.” These are in many of the other versions of the installation’s . . . “frames.” Several other texts in much smaller letters, some of them sentences, crossed the windows. I was enthralled with the way one could see through these texts into the pond, and the trees beyond, and–finally–into the sky (wonderfully cloud-clumped when we were there) . (Sound effects were included although only the ones for “WATER” were working at this time.)

I immediately thought of Bob Lax (a favorite p0et of Clark’s too, I learned). Clark is a big fan of Samuel Beckett’s (whom he’s been teaching many for five or more years), who is also an obvious influence. But he’s also absorbed and created out of many other influences, many of them non-literary.