Entry 1748 — A Different How-To Book

March 10th, 2015

While writing yesterday’s entry, I thought–as I often do–that I was giving a lesson, for writing about poetry often brings out a need in me to teach others to be able to appreciate, and thus enjoy, the poetry I write about as much as I do. Again today I thought about that while adding another passage to my notes of yesterday. Then it occurred to me that so far as I knew, no one had written a how-to book for beginning otherstream poets. Maybe I should. At worst, it would give me lessons that would take care of my daily blog entries.

I had another tough day, though, and wasn’t up to throwing together a lesson. One reason for the toughness of the day was that I’d come up with a good idea for my first lesson: the use of one of my own early poems as an example . . . but could not find the poem! I still don’t know where I hid it. But I eventually managed to remember how, or about how, it went, so I’ll be able to at least post that here:

sky's piecemeal white development down buildings' dark sides into tr;af:fi,c.

.

Entry 1747 — Some Bedside Notes

March 9th, 2015

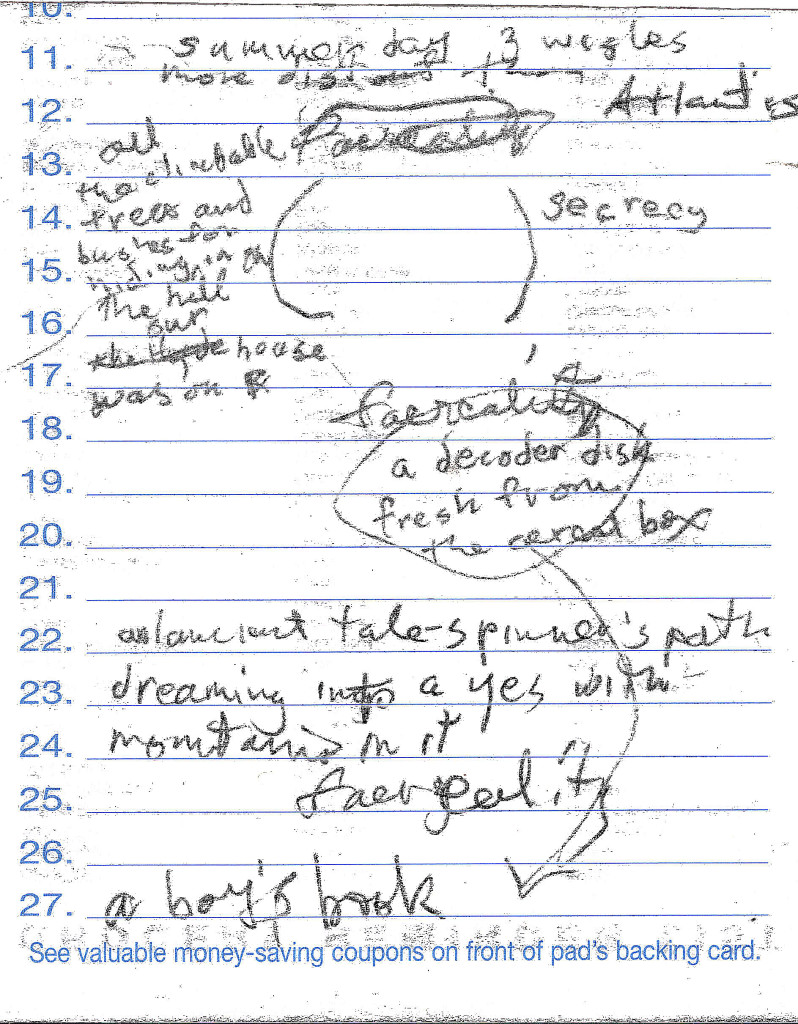

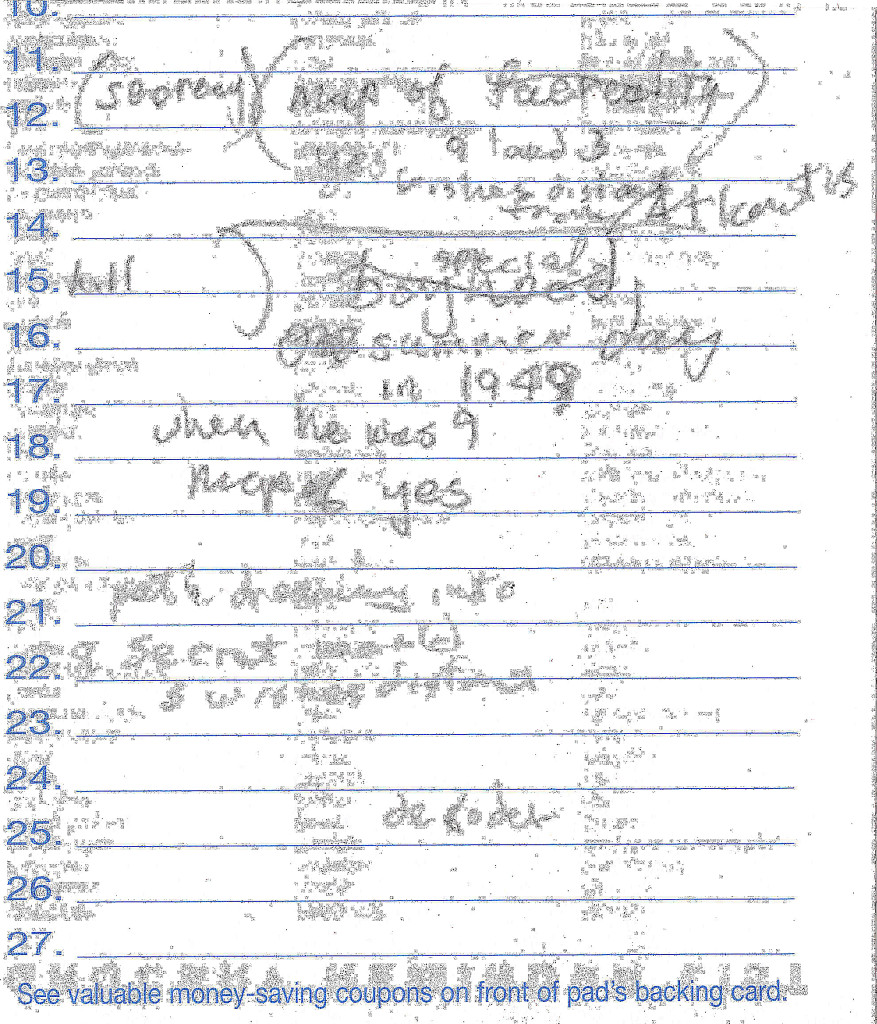

Some notes from a week or so ago that I hoped to make a long division poem of. I keep scrap paper at my bedside in case I have enough ideas I feel the need to record them while lying in bed at night. The second sheet are my notes about the previous notes. The poem I was preparing these notes for was to be the second in the set begun with the poem in Entrymy second long division of boyhood. Nothing further has come of these. Until now, when I’m having too tired a day to be able to think of anything else to put here.

For Easy Reading:

all the climbable trees and bushes for hiding in the hill our house was on

I like this but it is not worded properly and I still can’t see how to fix it–without simply sticking a second “on” into it.

a summer day three wishes more distant than Atlantis

This I find wonderful, the one really nice term I came up with.

faereality–actually a version in code that I didn’t want to take the time to work out, knowing I’d remember to later.

A continuing favored image of mine I want one day to have a cluster of poems about (and already have several).

a decoder disk fresh from the cereal box

I never had such a disk but wanted something about the making of codes that was so important to me as a boy.

secrecy (used as an exponent, an idea I dropped because–fancy this–it didn’t make mathematical sense to me)

Nothing more wonderful in boyhood than this.

an ancient tale-spinner’s path dreaming into a yes with mountains in it

A second fairly inspired term, particularly the “yes with mountains in it”

a boy’s book

Just a possible term if needed, and chosen because books were the ur-source of the best adventures of my boyhood.

I’m not bothering with the second page’s notes because none of them seem good to me–except the use of “secrecy” as a multiplier rather than as an exponent. The idea of a map of something ridiculous to have a map of, except in a poem.

.

Entry 1746 — A Possible Invention & A List

March 8th, 2015

himlli esyaen r txv eee scn tat li o n

An email from Richard Kostelanetz got me thinking about invented moves in writing of the kind he tries for–in everything he writes except his conventional prose works, it would seem. Result: the possible invention above. Its difference from all other such works is very minor, but does distinguish it from all other such works, if I really am the first to make such a thing. The are a great number of permutations of the basic idea possible. Would each be consider a lexical invention, I wonder. . . .

Now the list:

The Knowleculations, or kinds of knowlecular data in accordance with size

KNOWLEBIT smallest unit of knowledge

KNOWLEDOT all the knowlebits in a mnemodot[1]

KNOWLECULE the equivalent of a word’s worth of knowledge

KNOWLECULANE the equivalent of a sentence’s worth of knowledge

KNOWLECUMIZATION the equivalent of a paragraph’s worth of knowledge

KNOWLEPLEX the equivalent of a chapter’s worth of knowledge

KNOWLAXY the equivalent of a book’s worth of knowledge

KNOWLIVERSE a person’s entire store of knowledge

[1] a mnemodot is a single storage-unit in one or another of the cerebrum’s many mnemoducts; it is what all the percepts (i.e., units of perceptual data coming from the external or internal environment) and retrocepts (i.e., activated units or data stored as memories) of the kind the mnemoduct is responsible for that reach it during an instacon, or instant of consciousness [2]

.

Entry 1745 — Denial

March 7th, 2015

An “argument” far too often used in debates between the impassioned (I among them) is the assertion that one’s opponent is in denial. “Denial,” I suddenly am aware, belongs on my list of words killed by nullinguists. It has come to mean opposition to something it is impossible rationally to oppose. When used in what I’ll a “sweeper epithet” (for want of knowing what the common term for it is, and I’m sure there is one) like “Holocaust-Denial” (a name given to some group of people believing in something), it has become a synonym for opposition to something it is impossible rationally to oppose–or morally to express opposition to! Thus, when I describe those who reject Shakespeare as the author of the works attributed to him as “Shakespeare-Deniers,” I am (insanely) taken to mean that those I’m describing are evil as well as necessarily wrong. Now, I do think them wrong, and even think they are mostly authoritarians, albeit benign ones, but I use the term to mean, simply, “those who deny that Shakespeare was Shakespeare.”

Or I would if not having the grain of fellow-feeling that I have, and therefore recognizing that small compromises with my love of maximally-accurate use of words due to the feelings of those not as able to become disinterested as I am may sometimes be wise. Hence, I nearly always call Shakespeare-Deniers the term they seem to prefer: “Anti-Stratfordians.” But I have now taken to call those that Anti-Stratfordians call “Stratfordians,” “Shakespeare-Affirmers.

(Note: now I have to add “disinterested” to be list of killed words, for I just checked the Internet to be sure it was the word I wanted here, and found that the Merriam Webster dictionary online did have that definition for it, but second to its definition as “uninterested!” Completely disgusting. Although, for all I know, my definition for it may be later than the stupid one; if so, it just means to me that it was improved, and I’m not against changing the language if the improvement is clearly for the better as here–since “disinterested” as “not interested” doesn’t do the job any better than “uninterested,” and can be used for something else that needs a word like it, and will work in that usage more sharply without contamination by vestiges of a second, inferior meaning.)

Of course, to get back to the word my main topic, “denial,” means the act of denial, and indicates only opposition, not anything about the intellectual validity or moral correctness of it. Except in the pre-science of psychology where it means, “An unconscious defense mechanism characterized by refusal to acknowledge painful realities, thoughts, or feelings.” I accept such a mechanism, but would prefer a better term be used for it. For me it is a probably invariable component of a rigidniplex. Hey, I already have a name for it: “uncontradictability.”

No, not quite. It seems to me it is a mechanism automatically called into action against certain kinds of contradiction: facts that contradict the core-axiom of a rigidniplex, directly or, more likely, eventually. Maybe “rigdenial,” (RIHJ deh ny ul)? For now, at any rate. Meaning; rigidnikal denial of something (usually a fact or the validity of an argument) due entirely to its threatening, or being perceived as a threat to) one’s rigidniplex, not its validity (although it could be true!).

When I began this entry, I planned just to list some of the kinds of what I’m now calling “rigdenial” there are, preparatory to (much later, and somewhere else) describing how it works according to knowlecular psychology. I seem to have gotten carried away, and not due to one of the opium or caffeine pills I sometimes take. I’ve gotten to my list now, though. It is inspired by my bounce&flump with Paul Crowley, who sometimes seems nothing but a rigdenier.

Kinds of Rigdenial

1. The denied matter is a lie.

2. The denied matter is the result of the brainwashing the person attacking the rigidnik with it was exposed to in his home or school

3. The denied matter is insincere–that is, the person attacking the rigidnik with it is only pretending to believe it because the cultural establishment he is a part of would take his job away from him, or do something dire to him like call him names, if he revealed his true beliefs.

4. The denied matter lacks evidentiary support (and will, no matter how many attempts are made to demonstrate such support: e.g., Shakespeare’s name is on a title-page? Not good enough, his place of residence or birth must be there, too. If it were, then some evidence that that person who put it there actually knew Shakespeare personally is required. If evidence of that were available, then court documents verifying it signed by a certain number of witnesses would be required. Eventually evidence that it could not all be part of some incredible conspiracy may be required.

5. The denied matter has been provided by people with a vested interest in the rigidnik’s beliefs being invalidated.

6. The denied matter is obvious lunacy, like a belief in Santa Claus.

7. The rigidnik has already disproved the denied matter.

8. The person advancing the denied matter lacks the qualifications to do so.

9. The rigidnik, as an authority in the relevant field finds the denied matter irrelevant.

10. The rigidnik interprets the meaning of the words in a denied text in such a way as to reverse their apparent meaning. (a form of wishlexia, or taking a text to mean what you want it to rather than which it says)

11. One form of rignial (as I now want to call it) is simple change-of-subject, or evasion.

12. Others.

I got tired. Some of the above are repetitious, some don’t belong, others have other defects. Almost all of them are also examples of illogic. But the list is just a start. I’ll add more items to it when next facing Paul–who has a long rejoinder to the post I just had here.

Entry 1744 — An Organization for Culturateurs

March 6th, 2015

First something from a comment I made yesterday at HLAS when some wack brought up the quotation from Emerson cranks and others who can’t argue well love:

Emerson is a hero of mine, and I love “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statesmen and philosophers and divines.” But “With consistency a great soul has simply nothing to do. He may as well concern himself with his shadow on the wall,” is insanely stupid–the way the writings of Foucault and the other French literary critics whose idiocy has dominated academic literary criticism in the US for so long are. Perfect consistency is probably not possible, but maximal consistency–ULTIMATELY–is what all the largest minds try their best to end in, even Emerson, even if he might not have been aware of it in his need to be allowed to say anything he wanted to purely on the basis of how much he liked it rather than on the basis of how much reality it reflected.

“With consistency a philogusher (lover of gush) has simply nothing to do. He may as well concern himself with his shadow on the wall.” Grumman, 5 March 2015

Better the shadow of himself he sees on the wall than one of himself that he sees on the side of a hairy green & purple unicorn eating marmalade in a thunderstorm on the moon.

–Bob G. Hmm, I realize decades too late that I should have been signing myself “Bobb” rather than just “Bob.”

.

Entry 1743 — Hillary Clinton’s Latest Scandal

March 5th, 2015

As I have frequently said, I hate politics and wish I could totally ignore it. I’ve managed to keep it out of this blog most of the time, but wish I’d kept it completely out of it. Nonetheless, today–again for lack of anything else to post–I am reacting to a bit of political news making the rounds in conservative Internet circles: Hillary Clinton’s illegal non-governmental email system.

Here’s a quotation from Jim Geraghty’s conservative newsletter about it: “ABC News political director Rick Klein said he was at a loss to come up with an innocuous explanation for Hillary’s ‘home-brewed’ system. There is no innocuous explanation. The whole point of it was to create an e-mail system that Hillary and her team would control completely, that would be beyond the range of federal record-keeping rules and laws and beyond the range of FOIA requests. If any message seemed embarrassing, politically inconvenient, or incriminating, she could erase it, and rest assured it was gone forever, beyond the reach of any investigator, FOIA request, or subpoena.”

I’m no fan of Hillary’s, but in this instance I’m on her side. I oppose sunshine laws. Politicians, and everyone else, in a free country, would be allowed to meet and discuss things in private. Let the voters vote for or against them on the basis of the laws they favor and oppose, and vote for and against, who cares why. Here’s my most horrible thought: if a politician promotes some law I favor, or–more likely–works to repeal some law I hate, I don’t care if he is doing so because bribed to. In fact, I have nothing against bribery since those with the most are more likely to be right than those with less.

Okay, that would only be true in an economically much more free country than ours is where making money depended on how good your product was, not in how good you were at getting the government to make laws against your competitors, or grant subsidies to you, etc. Not, in other words, based on the kinds of legal briberies so widespread now.

To get back to the sunshine laws. The main thing about them that bothers me is how inhibiting it would be to know that you are in effect revealing all your relevant thoughts to everyone whenever you try to work what you think should be done about something your office is in charge. Plus the extreme difficulty (I should think) of finding out what others think.

It makes me thing of the ridiculous hate laws, which are developing into laws against saying anything that a hyperoffendable finds demeaning or negative in any way. One of the books I’ve always wanted to write but never will would be a defense–nay, a celebration–of anger.

As for sunshine laws, I also dislike them simply because they are laws, but mostly because I am a zealot about freedom of speech, which I think should be total. In other words, it should include the freedom of silence and concealment. I should be able to say anything I want to–and say it privately if I want to. And say nothing if I want to. No fifth amendment right but the absolute right to say, “that’s none of your business.”

I’m over 500 words so ending this minor rant. It ain’t likely I’ll say anything of consequence. But I may be the first one utterly to oppose sunshine laws. No, I can’t believe no one else has, but I don’t keep up with stuff like that. An irony of my being against them is that I probably reveal more vile things about myself than about anybody. But that’s mainly because this blog is so private. I guess. Actually, if ten million people suddenly began reading my entries, they’d probably stay the same. Mainly because I’m no longer young enough for it to make any difference to me what others think of me.

Oh, one thing that is against Hillary is that she broke her contract with the government since using the government’s email system for all her government-related emails was part of it. I lean toward breaking stupid laws, though. Too bad she didn’t have me working for her: I’d have had a censor letting emails that were innocuous go to her private email system and to her government system, but only questionable ones going to the former. If Hillary could find a way to finance it, I’d hire experts to revise the questionable ones and put the revisions into the government system before sending the originals to the private system.

.

Entry 1740 — Of Meaning & Meaningfulness

March 2nd, 2015

I think a lot of gush and counter-gush in philosophical discussions has been caused by the use of the word, “meaning,” to mean two different things: (1) a description of a named entity in material reality that relates it to one or more named and defined entities in material reality in such a way that a person knowing the language its name is part of will, upon hearing or reading that name, be able to distinguish it from what it is not—by pointing to it on a table or the equivalent; and (2) a description of some real or alleged function of a real or unreal named entity that allows the entity to carry out or contribute to the carrying out of some mission important to whoever defines it as having this kind of meaning.

I’m satisfied with my definition of the first meaning of “meaning,” but consider my definition of the second meaning rough. The following examples should help clarify it:

Keats’s bust of Shakespeare had a great deal of meaning for him for reminding him of the possibilities of poetry. That is, the function of the bust was its help in encouraging him to follow Shakespeare’s lead as a poet.

The New Testament has a great deal of meaning for a sincere Christian for reminding him that Jesus died to allow him a chance for Heaven–i.e., its function (or one of its many functions) is to remind a Christian that immortality is possible.

Winning the first world series game has special meaning for a baseball manager because winning the first game in the other team’s ballpark gives a team an advantage, and winning it in one’s own ballpark prevents the other team from having an advantage–i.e. winning the first game regardless of where played has the function of increasing a team’s chance of winning the series (in addition to the advantage an victory will have.

Each time I list one of these “meanings,” it is plain to me that the word I should be using is not “meaning,” but “meaningfulness.” So my simple insight concerning the meaning of “meaning,” is that the second meaning should be junked. The main place it crops up is in the phrase “life’s meaning.” I maintain that “life’s meaning” should be, simply, “a state of being certain entities in material reality possess which allows the entity to move of its own volition, and in other ways act as living organisms in accordance with the latest scientific understanding of the state,” not “life’s purpose.” If you want to discuss the latter, the correct term should only be “life’s meaningfulness.”

And the question central to much of philosophy should be, “What gives life meaningfulness? not what gives life meaning? Linguistics with the aid of biology gives the word, “life,” its only proper meaning, a meaning that it is important to point out is objectively-arrived at, because based solely (for the rational) on the material attributes of the state of being the word, “life,” represents. (I’m ignoring the inexpressible intangibles those who believe in the existence of immaterial entities or substances consider part of life’s state of being as irrelevant because either non-existent or existent but not material, so incapable of having any effect on anything.)

There, another attempt to form a minor understanding of an over-rated question without great success. But if I’ve only gotten a few people to use “meaning” only in its linguistic sense, never in its philogushistic sense, I’ll be happy.

.

Entry 1739 — In the Eurekan Zone

March 1st, 2015

I often write here about being in my null zone, or almost in it. I guess I’ve mentioned a few times I’ve been in a good zone. I rarely mention being in a good zone, though: I’m too involved with more important things to. When I’m in my null-zone, though, I tend not to have anything else to write about. Anyway, a few minutes ago, I was getting all kinds of ideas. I was feeling energetic and enthusiastic. It was like I felt for about an hour while writing about the rigidniplex. Ergo, I should call where I was the “eurekan zone.”

I was not in it for long, not wholly in it for long. I feel mentally in it at the moment, but physically in the null zone, and in a so-so mood. My mood may be good enough to allow me to take care of the entry–if I can remember any of the ideas I had.

One was simply my counter to something I read in the latest issue of The New Criterion about how foolish so many thinkers were for believing that “a hard science of human affairs has been or soon will be achieved.” I think a poor hard science of human affairs has been achieved, and that neurophysiological understandings will eventually make it equal as a science to chemistry in hardness, especially once academics are aware of my theory ( . . . I hope).

Gary Saul Morson, the writer whose words I quoted against the notion of hard science because if political science were a hard science, there would be no room for reasonable doubt for the same reason there is no room for reasonable doubt about most aspects of chemistry. I find this no problem because (1) however hard a science is, it will never be complete, so there will always be important differences of opinion.

ns about aspects of it; and (2) the axioms chosen to base a given hard science on will necessarily be a subjective matter, so squabbling at the roots of political science will always occur.

It may be exclusively the moral axioms of physical science that people will argue about, as they do now: for instance, which is better, a collectivist society or an individualistic one? Answer: it would depend on whom you ask. Security versus freedom. The first is better for certain people, the second better for others. Which is why our nation and others mix the two. But how much of either is the right mix will always be debatable.

* * *

I’m definitely out of my eurekan zone. While briefly in it, I coined a few new terms, as I tend to do when I feel at my best. One was “conclusory,” which consists of verosophical conclusions and the actions taken because of them. I was thinking about the many people involved in the sciences who are not seeking important understandings of anything but using the conclusions such understandings lead to as the basis of technological accomplishments. But that would mean they are working in technology, so “conclusory” is not needed.

“Techthetics” was my word for the equivalent field in Art. It would be for the technological use of art for decoration. I was trying to differentiation those artists who advance their art from mere “techthetists” who just use received art to make salable paintings that go nowhere man has not been before. But the umbrella term “technology” covers such people as readily as it covers those whose field is applied science. So, good-bye “techthetics.”

* * *

.

.