On Writing To Be Seen, Volume One

Several anthologies of visual poetry were published around 1970 in this country, Anthology of Concrete Poetry, 1967, edited by Emmett Williams; anthology of concretism in Chicago Review, 1967, then as a separate book, 1968, edited by Eugene Wildman; Concrete Poetry, A World View, 1968, edited by Mary Ellen Solt; Once Again, 1968, edited by Jean-Francois Bory; This Book is a Movie, 1971, edited by Jerry G. Bowles and Tony Russell; and Open Poetry, 1973, edited by Ronald Gross & George Quasha with a visual poetry anthology of around 150 pages within edited by Emmett Williams (and A found Poetry section with some works that might pass for visual poetry edited by John Robert Colombo. Then no more appeared for quite a while. Visual poems kept being composed, though—enough of them toward the end of the eighties to make it clear that we were ready for another visual poetry anthology. Lots of visual poets, particularly those in the post-70s-anthologies generation, jabbered about having one done, but nothing happened until around the autumn of 1999 when Crag Hill and I up and decided to get one done. It was hard work but Writing To Be Seen, Volume One was the result. More volumes were planned, one of them completed except for conversion to a form readable by computer-driven printers, but none published.

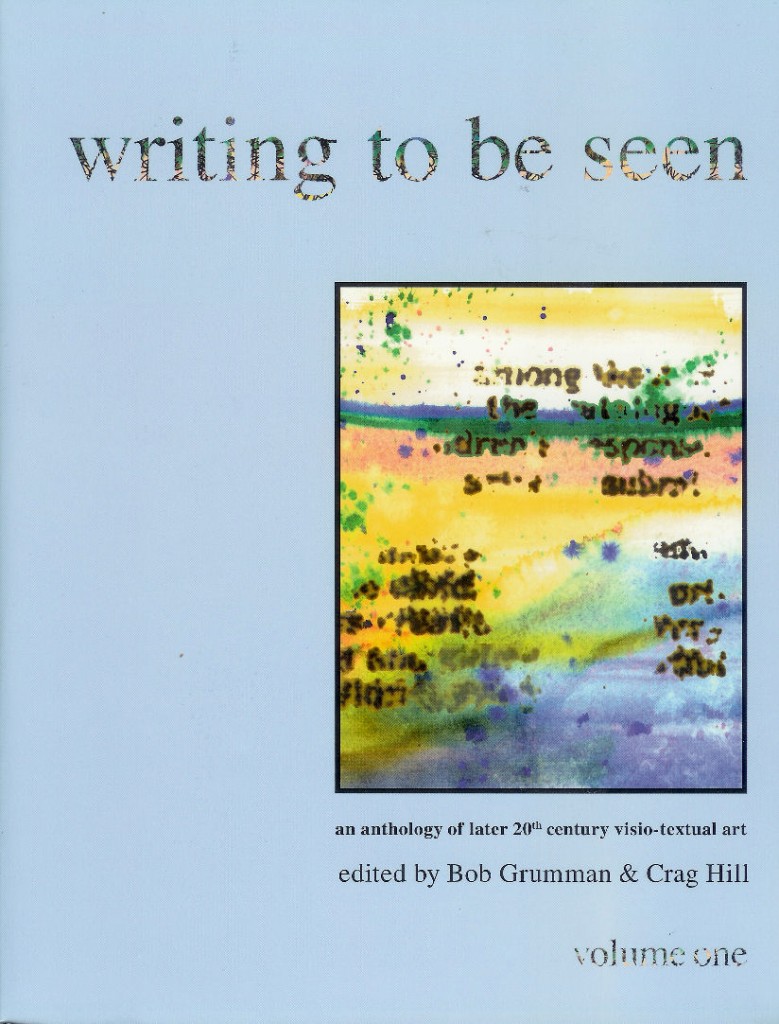

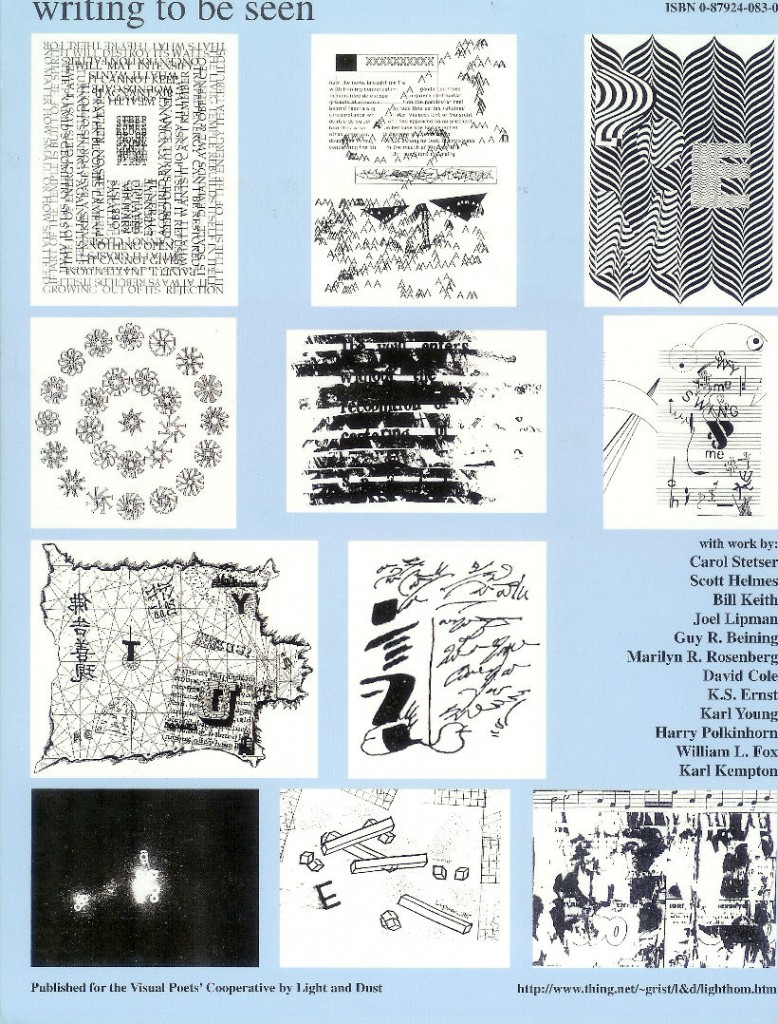

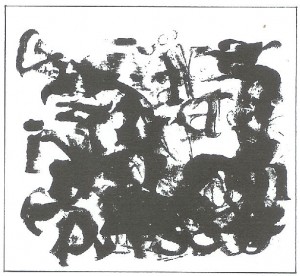

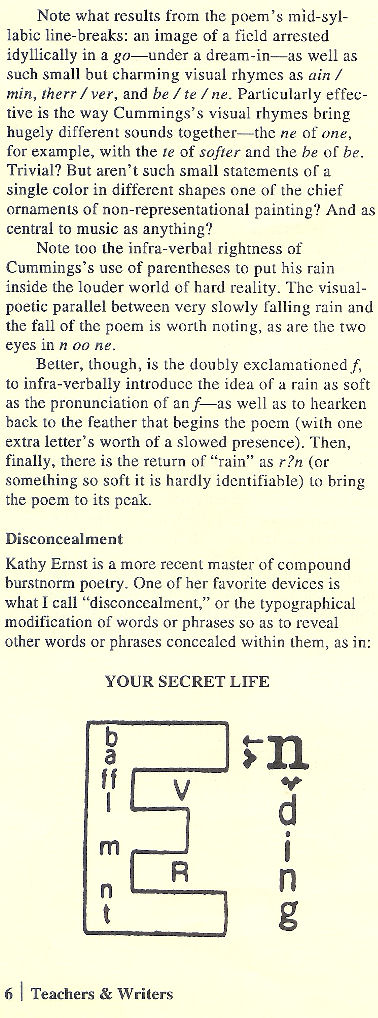

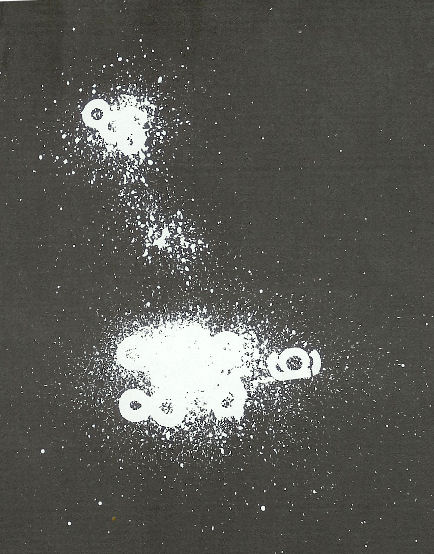

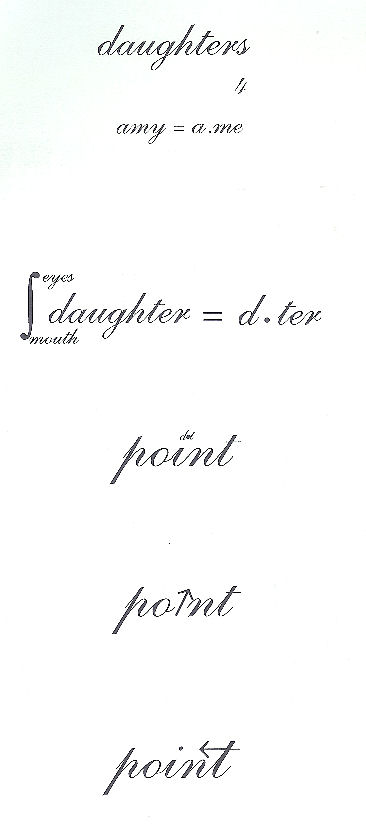

This essay is an attempt to present a rough idea of what is in Writing To Be Seen via samples of each contributor’s work, with my comments on them. I welcome feedback. I’ll start with the cover illustration by K.S. Ernst, which I consider alone worth the $24 price of the anthology. Next is the sample of the works within on the back cover, though not reproduced quite as nicely as I would have liked (because of my own limited technical means at the time). They indicate the collection’s breadth and excellence.

.

- Front Cover, by K. S. Ernst

- .

- A large print of Kathy’s work is one of only two visual poems I have on the walls of my house. I’d like to have more but all my bookcases full of books leave little room for hung art. The other visual poem on my walls is a second-rate one of my own that I only hung to see what it’d look like hung, then have been too lazy to take down (mainly because then I’d have to find a place to put it and and finding places to put things in my house is a major enterprise).

- .

-

.

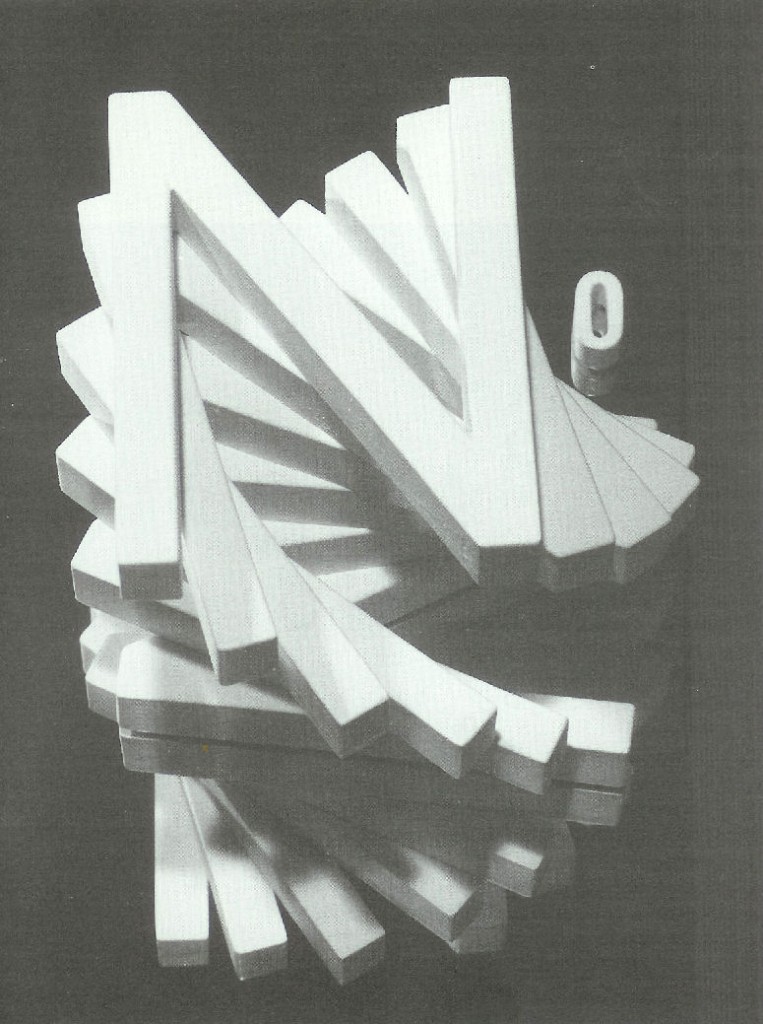

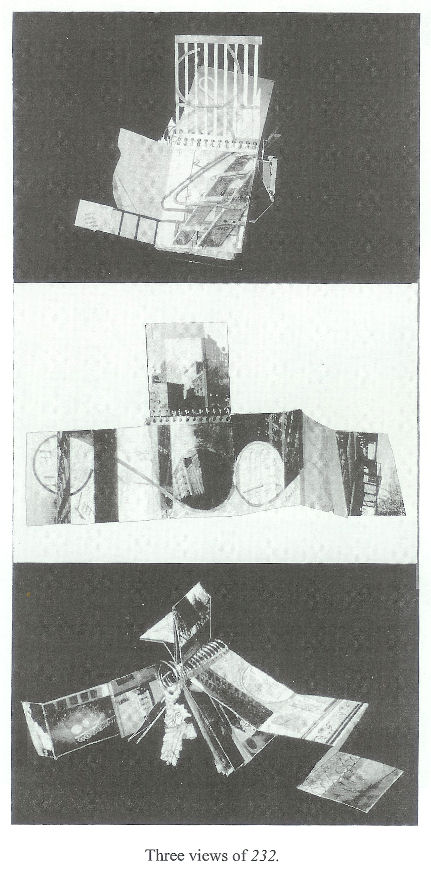

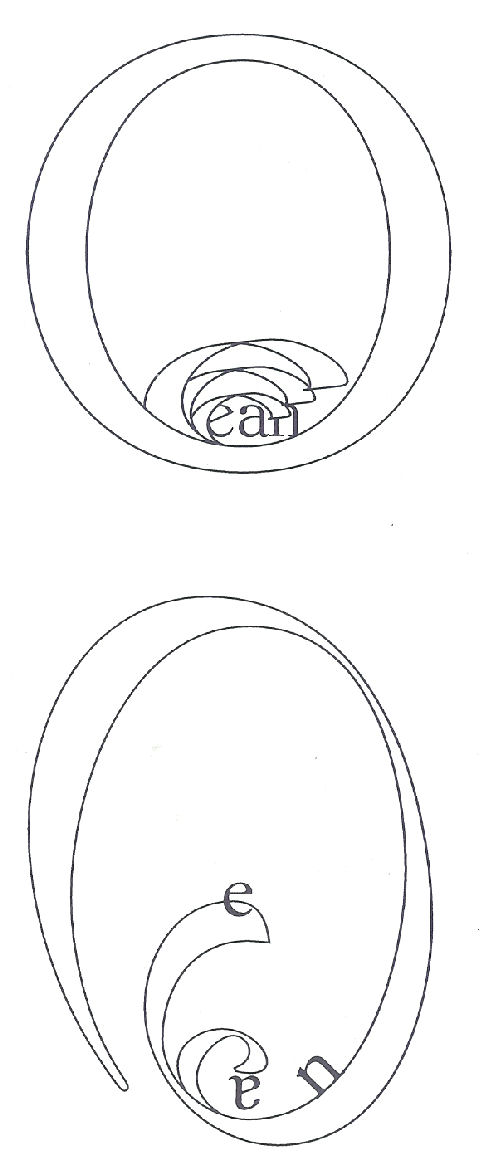

Below is a great visual poem–visiosculptural poem, I should say, as it’s a photograph of a work in wood—by Kathy Ernst. I chose it as them lead poem from <em>Writing To Be Seen</em> for my essay because it is not only great but because I find it hard to believe anyone could resist its appeal. Each contributor has twenty pieces, plus any extras they may have included in the Artist’s Statement each was asked for. That, by the way, was the feature of the anthology that I was most proud of, for I was the one who first brought it up, and suggested giving each contributor a lot of pages for it–twelve to fifteen, I think. and these are big letter-sized pages. But Crag was all for it, too. Not all the contributors took advantage of it, but Kathy wrote a terrific “personal history,” illustrated with a number of specimens of her work. Ditto Joel Lipman. Karl Young went a step further in combining discussion and art by combining his statement and selection of works.

.

.

One of the controversies raising a bit of a stir while Crag and I were putting the anthology together was my suggested subtitle for it, “an anthology of later 20th-century visio-textual art.” Crag was with me on it, others not, but somehow I won, I’m not sure how. I felt, and still feel, that a general term for pieces that some would call poetry, some not, is preferable to a polarizing term like, “visual poetry.” No question, I also had and have a vendetta against calling wordless graphic designs “visual <em>poetry</em>.”

. -

-

.

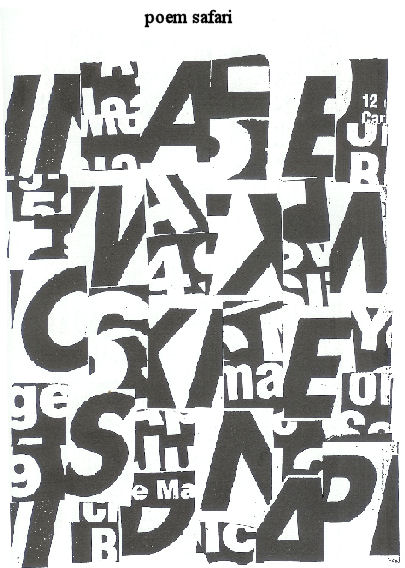

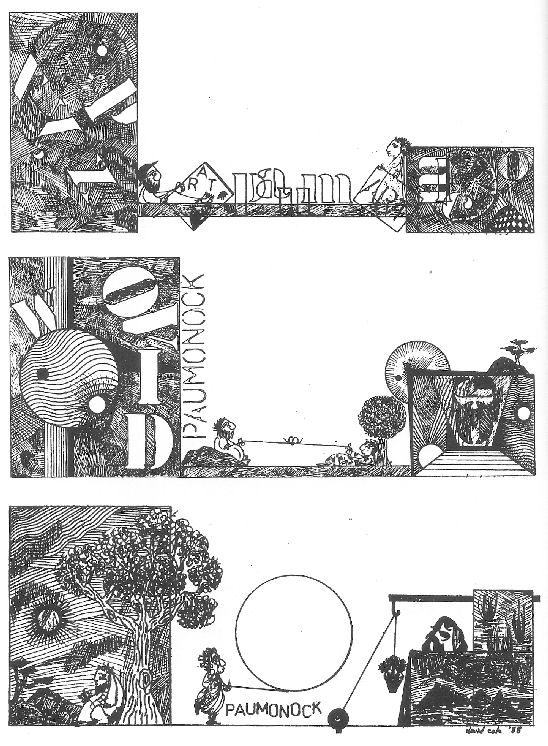

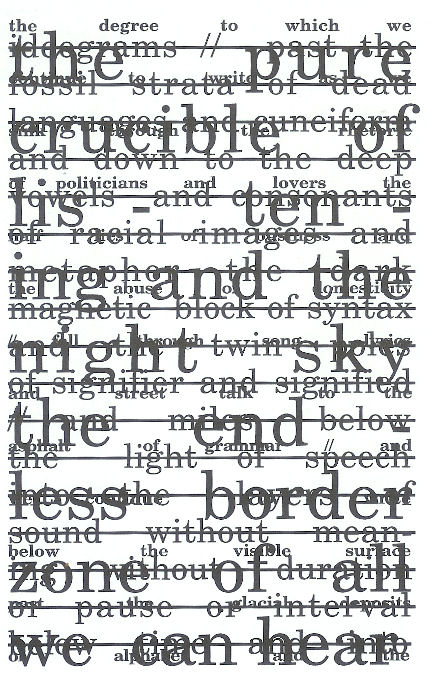

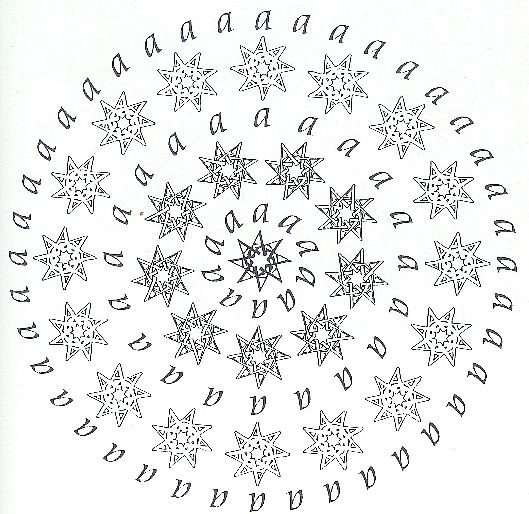

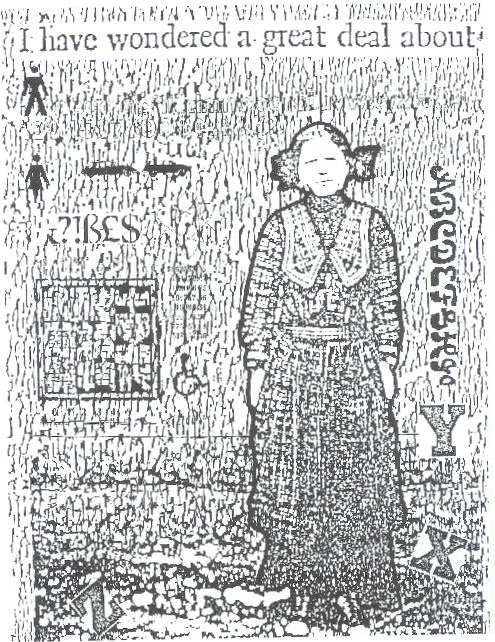

. It was works like the ones above of Carol Stetser's that I felt "visio-textual art" best suited for. I admire the two works in question, and admit that they certainly are close to being poems. I'd call them "language visimages"--because they visually depict (are "visimages" of, in my admittedly obscure terminology) language, or language concerns. The first, I must confess, I can't really figure out. The alphabet is there--

. It was works like the ones above of Carol Stetser's that I felt "visio-textual art" best suited for. I admire the two works in question, and admit that they certainly are close to being poems. I'd call them "language visimages"--because they visually depict (are "visimages" of, in my admittedly obscure terminology) language, or language concerns. The first, I must confess, I can't really figure out. The alphabet is there--and an old wise woman/Mother-figure/school-marm. A misty wondering eroding

in places into the beginning of verbal meaning, and/or the beginnings of

linguistic paths to meaning? I found the origin of language theme so strong

when Crag and I were sequencing the anthologies contents, though, that we

picked this one as the first in Carol's section, and Carol's section--which

deals much with the same theme (in part, since all her work complexly goes

manywhere)--as the lead section of the book. (That her work is so immediately

The second of Carol's pieces I think even less visio-poetic than the first,

for it doesn’t even have an imbedded captian–but I like it even more.

impressive was another reason for our choosing it to open our book with.)

Maybe that’s because I think I have a firmer handle on it: I deem it an

archaeological site, with various layers of languaging exposed back to the

stone age. Included are fragments of alpahabet–the “def,” which is a

fragment of alphabet that abbreviates “definition” with wonderfully

appropriateness, near the top left, and the “AB” near the bottom left

(with smaller fragments of each near the middle) among them. Archaeology,

astronomy, cartography, anthropology–these are key subjects of Carol’s

>work here. Why she isn’t better-known I won’t ever figure out.

.

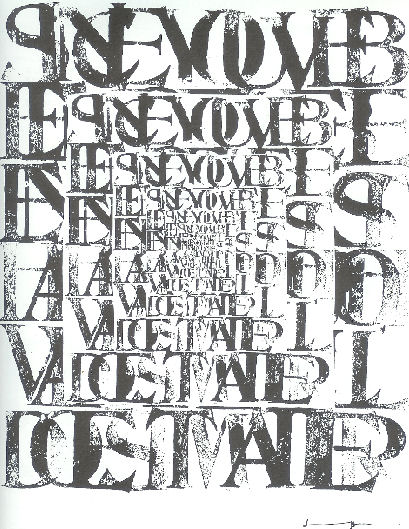

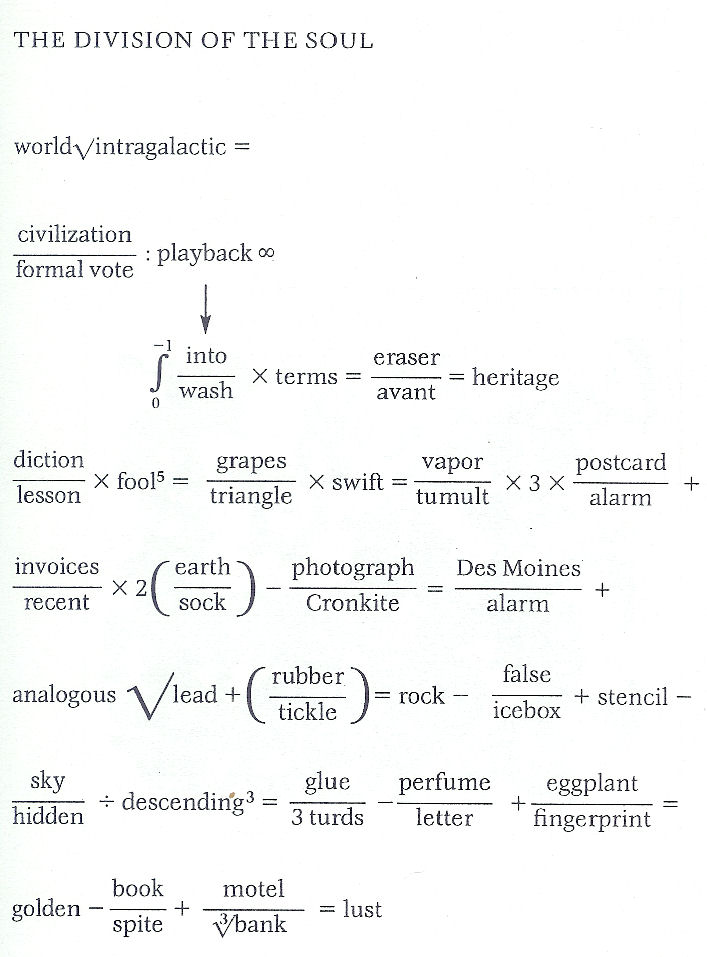

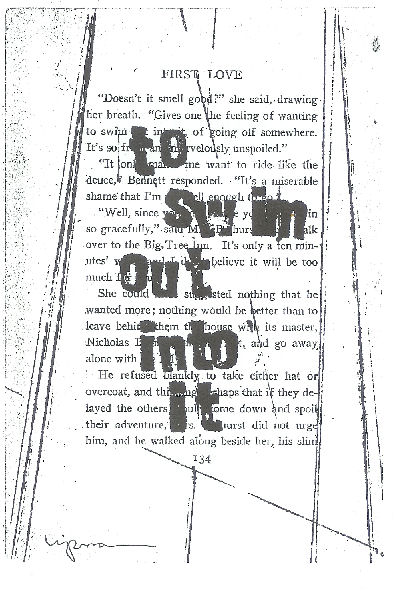

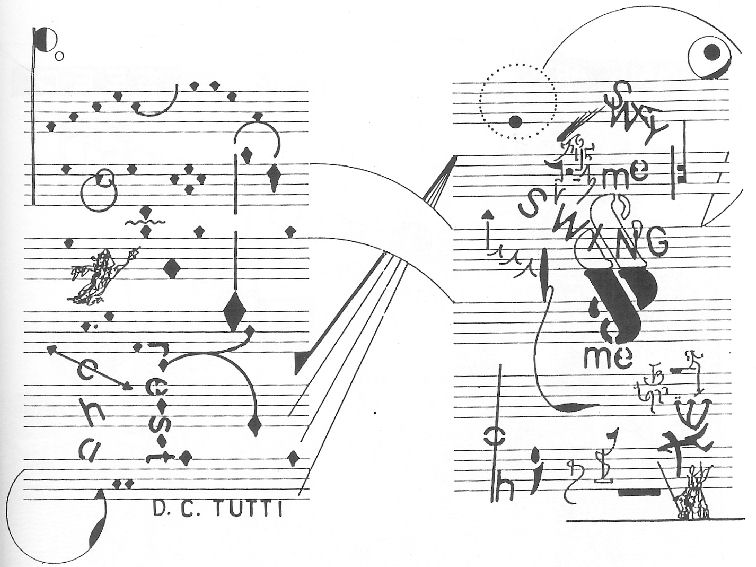

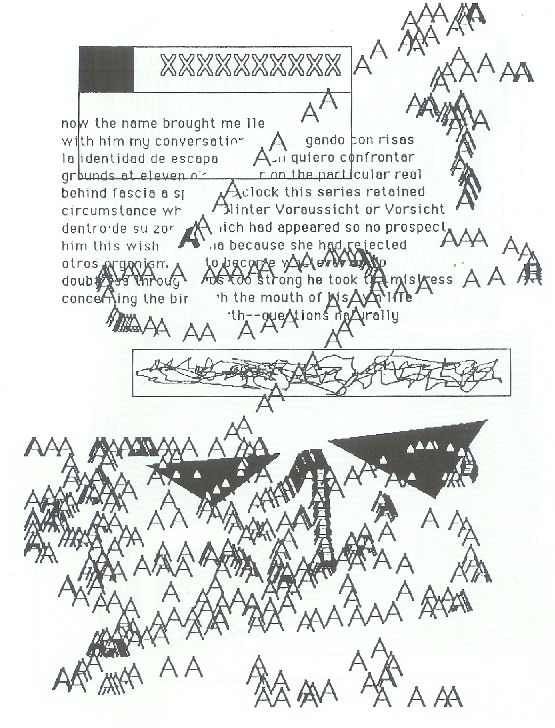

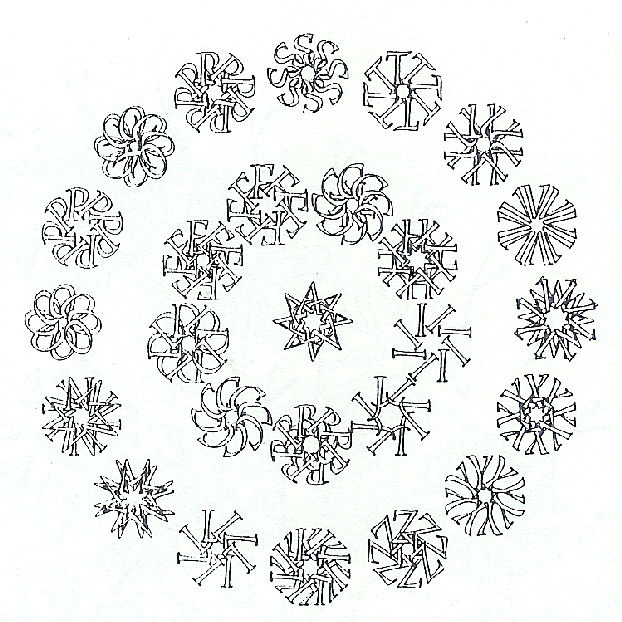

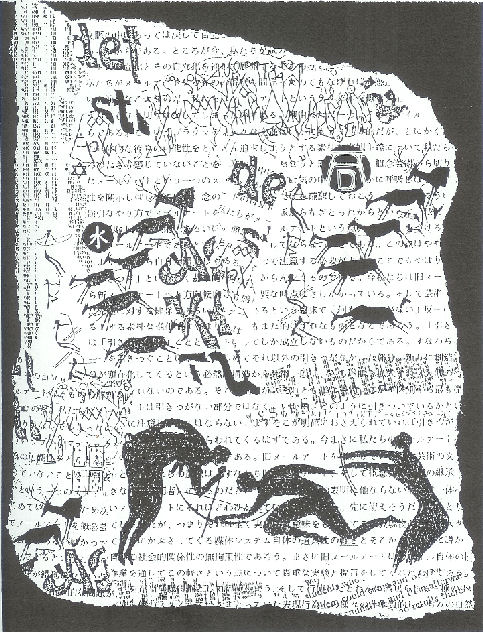

Number three of the poets with work in <em>Writing To Be Seen</em>

is Scott Helmes. Here are his “Since You’ve Been Gone” and “Freud”:

..

.