Archive for the ‘Literary Opinion’ Category

Entry 1203 — More Boilerplate About Academics

Wednesday, September 4th, 2013

According to Gary Soto’s bio, his poem, “Oranges,” is the most antho-logized poem in contemporary literature. When Jim Finnegan reported this to New-Poetry, I replied, “Sounds like something an academic would say after checking six or seven mainstream anthologies. I may be wrong, but I doubt anyone can say what poem is more antholo-gized than any other, mainly because I don’t think anyone can know about all the anthologies published.”

Jerry McGuire responded to this and that resulted a little while ago (3 P.M.) in the following:

Bob, does it really take an academic to persuade you that a particular instance doesn’t prove a general claim? Even averaging things out, I suspect, people who write poetry for their own purposes–which are enormously varied and not in dispute–don’t strike me as “more adventurous” though I can’t for the life of me figure out what kind of “adventure” you have in mind) than academics who write poetry, some of whom are conservative, some middle-of-the-road, and some well out there beyond the fringe. If you mean, by the way, that academic writers are more likely to respect more elements of the history of poetry and include a greater historical variety among their preferences, perhaps I’d agree with you, intuitively, but I can’t prove it and I doubt you can either. As for “academics are in charge of poetry, and I include many people not employed by colleges as academics. An academic is, by my definition, by innate temperament, an automatic defender of the status quo,” your definition strikes me as self-serving and petty. What you know about my “innate temperament” (“for instance”?) hardly qualifies you to determine what’s “automatic” in my preferences, loves, hates, and particular decisions. As so often, you seem to be nurturing some sort of long grudge, and using the list to air your brute generalizations. Some of us do read these things, you know. And while crude prejudices don’t hurt my feelings–hardened over the years by the contempt of 18-year-olds for their elders–they sadden and disappoint me.

Jerry

On 9/4/2013 1:01 PM, Bob Grumman wrote:

I would claim that academics are much less adventurous (for good or bad) than non-academics–in general. Compare, for instance, the anthology that I would edit if allowed to the anthology David Graham would. Or, hey, compare the one he did edit (on conversational poetry, if my memory hasn’t completely died) with one I edited (on visual poetry). Ignoring which was better (and believe it or not, I would certainly be willing to say they were equal but different in spite of my preference for the poems in mine), consider only which would be considered more adventurous.

Jerry, I used a particular instance to illustrate a general claim. Maybe if I was able to find everything I’ve written on the subject, I could present a fairly persuasive case for my academic/non-academic division but I’m not, so for now will simply have to leave my opinion as just another Internet unsupporthesis. I’ll not be able to get into what adventurous is, either, except to say that Columbus was more adventurous than Captain Shorehugger because he went where none or almost none went while the cap’n went where many had been. The comparison holds even if the latter had found many things of value that had been overlooked by other shorehuggers (which is what the best academics are good at) and Columbus had sunk a hundred miles west of the Azores.

(Note, I can’t lose this argument because I define those you would call academics who are “well out there beyond the fringe as non-academics” since I believe that one employed by a college isn’t necessarily an academic, John M. Bennett and Mike Basinski, two Ph.D. college librarians [but neither of them with any clout at all in the poetry establishment] being cases in point.)

modestly yours, the World’s SUPREME Poventurerer

* * *

Jerry also wrote:

As for “academics are in charge of poetry, and I include many people not employed by colleges as academics. An academic is, by my definition, by innate temperament, an automatic defender of the status quo,” your definition strikes me as self-serving and petty. What you know about my “innate temperament” (“for instance”?)hardly qualifies you to determine what’s “automatic” in my preferences, loves, hates, and particular decisions. As so often, you seem to be nurturing some sort of long grudge, and using the list to air your brute generalizations. Some of us do read these things, you know. And while crude prejudices don’t hurt my feelings–hardened over the years by the contempt of 18-year-olds for their elders–they sadden and disappoint me.

Jerry

in a second post, I wrote:

I skipped the above, mistaking it for just a repeat of what I’d said in my post. I definitely have a long grudge, but when you ask what I know about your innate temperament, I’m afraid a possibly over-sensitive buzzer of yours made you take my words as personal. If you read what I say with care, you will see that I say nothing that would indicate that I consider you an academic, by my definition. I would say offhand that you are surely more of an academic than I. From what I’ve read of what you’ve written, I am sure, too, that you are much less of an academic, by my definition, than the people at the top of the poetry establishment. Just as I am, from some points of view, a terrible academic, since I believe artworks with no words of aesthetic significance cannot be poetry; that a good poem HAS to have some unifying principle (although it may be very difficult to discover and may even be chaos), that what I call otherstream poetry is just a different kind of poetry, not a better kind; that literary criticism is as valuable as poetry; and many other opinions.

Now for a little snarkiness: the belief that academic are not automatic defenders of the status quo is as crude as the belief that they are. And my belief that the majority of those making a living in college English departments are automatic defenders of the status quo is not a prejudice but the result of quite a bit of study and thought, however misguide others may think it. So there. True, an academic study of academics would be helpful if thorough and honest. How about a comparison of all the poetry critics on a list of poetry critics with writings in publications almost everyone would agree are mainstream, like Poetry and The New Yorker and those on a list of those who have written a reasonably large amount of poetry criticism just about never in such publications–like I. You could include the language poetry critics active before 1990, when language poetry became what I called “acadominant,” meaning widely accepted by academics as important, even by the many against–who showed they thought it important by campaigning against it. It proved me right by being confirmed as the right edge of Wilshberia around 1900 with the acceptance of a language poet into the American academy of poets, and mainstream anthologies of language poetry. Something of the sort will eventually be done, but not for several decades, I suspect.

–Bob

.

Entry 1190 — My List

Thursday, August 22nd, 2013

I somewhat angrily believe that every poet on my little list of yesterday (and many others–how did I manage to leave Ed Baker off it, I just thought) merits a book-length critical study. And will get more than one fifty years from now from the kind of academics now writing about Lowell and Ginsberg. Anyway, the one on John Martone will be especially interesting as a study of a representative bridge between the knownstream of our time and its otherstream–via haiku. LeRoy Gorman is another such–and possibly I, with a bunch of conventional haiku in print and an early collection of visual haiku.

I’m basically taking another day off due to being nine-tenths non-sentient again. So that’s it for this entry . . . except another coinage: recogrization. When a person taught that Hartford is the capital of Connecticut is asked what the capital of Connecticut is and says, “Hartford,” he has shown he has successfully memorized the datum; if he cannot answer but picks “Hartford” out of a list of four cities as the answer, he has shown he has successfully recogrized the datum. I’m good at recogrization but not at memorization (although I was a whiz at it before learning how stupid it was).

.

Entry 1189 — 10 Important American Othersteam Poets

Wednesday, August 21st, 2013

Ten Important American Othersteam Poets

John E. Bennett

Karl Kempton

Guy Beining

K.S. Ernst

Marilyn Rosenberg

Carol Stetser

John Martone

Scott Helmes

Karl Young

Michael Basinski

My list’s title demonstrates one reason I’m so little-known a commentator on poetry: it doesn’t scream that it’s of the ten best American Otherstream Poets, just a list of a few important ones. What makes them “otherstream?” The fact that you’ll almost certainly not find them on any other list of poets on the Internet.

This entry is a bit of a reply to Set Abramson–not because I want to add these names to his list but because two of the names on it have been doing what he calls metamodern poetry for twenty years or more, as far as I can tell from my hazy understanding of his hazy definition by example of metamodern poetry. Both are extraordinary performance poets mixing all kinds of other stuff besides a single language’s words into their works. I would suggest to Seth that he do a serious study of them, or maybe just Bennett, whose work is more widely available on the Internet, and who frequently uses Spanish along with English in it. It would be most instructive to find out how metamodern Seth takes Bennett to be, and what he thinks of him. Warning: Bennett’s range is so great that it’s quite possible one might encounter five or ten collections of his work that happen to be more or less in the same school, and less unconventional than it is elsewhere, so one might dismiss him as not all that innovatively different.

Which prompts me to e.mail John to suggest that he work up a collection that reveals something of his range by including one poem representative of each of the major kinds of poetry he composes. So, off am I to do just that

.

Entry 1183 — Seth Abramson’s Latest List

Thursday, August 15th, 2013

Seth Abramson has posted a new list at the Huffington Review. Basically it’s a list of those poetry people he wants to like him–al the main members of the American Poetry Establishment, and a sprinkling of other knownstreamers hoping t get into the Establishment one day. He calls it “The Top 200 Advocates for American Poetry.” Needless to say, no one who main poetry interest is visual poetry is on it. I was hoping Dan Schneider would be on it, but he wasn’t. It seems of close to no value to me, even from the point of view of knownstreamers. Everybody in the field knows who the bignames Abramson names are, and the no-names will make little impression among so many other names.

I posted a negative comment to Abramson’s blog that never appeared–because he’s a jerk as well as incompetent, or just due to some Internet glitch, possibly due to me? Can’t say.

I didn’t try to post another comment at Abramson’s blog but said a few things about it at New-Poetry, where it got the usual small flurry of attention Abramson’s lists always get there. After wondering what happened to my comment, I said, “Anyway, here’s my final opinion of (the list): a long, boring cheer for the status quo in American poetry that ignores the full range of contemporary poetry.”

As I later wrote at New-Poetry, if I were making a list like Abramson’s, I’d call it a list of people doing . . . a lot for contemporary American Poetry and limit it to ten names or so. Three on it would be Karl Young, Anny Ballardini and James Finnegan (who runs New-Poetry). I later remembered Geof Huth, who should certainly be on it. I thought maybe one or two that are on the other list deserved to be on it, but certainly not most of them–although probably just about all of them are doing good things for their small section of mainstream poetry.

Tad Richards (who actually said at New-Poetry that I should be on the list!) wondered if “representing a small section (was) really a reason to be left off the list.” I replied, “Not a list of 200+ names, no. I was speaking of my own list of TEN people doing good work for contemporary American Poetry. Of course, we’re in an Internet discussion, so consisting of comments not necessarily thoroughly thought out, at least from me. I can see the value of promoting just one kind of poetry–IF few others are bothering with it. And, sure, even if someone is writing about Ashbery and able to say something new about him, that’s a contribution. BUT, I say, not enough by itself to put that person on my list.

“While speaking of my list, I would add that it would only be of publishers, editors and critics. They are the ones in positions to really do something for poetry. Of course, many of them can also be poets. And teachers–but only if they also are publishers, editors or critics. What we desperately need, I believe, are visible writers directing people not to poets but to schools of poetry they might enjoy, and not just pointing, but saying what the members of the schools are doing and how to appreciate it. Who on Seth’s list is doing that–for more than one or two schools?

.

Entry 905 — My Thought for Today

Sunday, October 28th, 2012

Having become more involved in the discussion at Spidertangle of the new vispo anthology than I intended, lots of thoughts about anthologies, criticism, poetry-evaluation, the field, poets, etc., have been bouncing around between my ears. One thought I had that gave me a great deal of pleasure, in good part because of how much others in the field will disagree with it, is that I believe that if I were the very first person to advance a judgement of an artwork, and supported my opinion with competent reasoning, then my judgement should be considered the Sole Judgement of the work until such a time as someone else offered a second opinion, with the support of competent reasoning–even if before then twenty others said I was wrong but failed to support their views with competent reasoning. In such a case, I would consider my judegement significantly more likely to be right than it had been because twenty people had attacked without presenting anything against it.

Of course, nothing like the above ever happens in real life because competent reasoning is disdained, especially by poets. I take that back. Certainly nothing like that happens in the short run. The main judgement of almost any artwork depends on how many “like” buttons have been push on its behalf. But in the long run, it may be that the ten or fifteen pieces of intelligent discussion about an artwork, or art oeuvre, or art school become recognized as such and absorbed by enough intelligent people to counteract all the unsubstantiated short-term judgements of it (or, in no small number of cases, agree with it).

.

Entry 834 — More of My Boilerplate at New-Poetry

Saturday, August 18th, 2012

On 8/15/2012 7:42 AM, bob grumman wrote:

Perhaps it’s wrong of me to be bothered by a mainstream critic’s being ignorant of or indifferent to the only significant thing I believe has happened in American poetry over the past century, the discovery and increasingly interesting use of (relatively) new techniques, but I am.

I still don’t have time for you, Jerry, but I’m going to reply, anyway! (Feel honored.)

An individual can’t avoid indifference about some things (like my indifference to the squabbles of the republicrats), but no field’s establishment (and every field has one) should be indifferent about something like visual poetry that a sizable number of people in its field think is important. It took me a long time to accept language poetry (genuine language poetry such as Clark Coolidge’s) as anything but nonsense (although not as long as it took me earlier to accept free verse—although I instantly accepted Cummings’s visual poetry very early when shown what it was doing), but I finally did, because so many people to me were enthusiastic about it. Not that I can accept every poet’s work that others find terrific, but I try to. I’m still working on Gertrude Stein’s.

Some even do both! At the same time! You’d never know it from reading any of the books of criticism Finnegan tells us about.

Definitely.

Not sure what you mean by “ensembles.”

I suspect you’d have any easier time getting one (from a “real” publisher) than I would for any book of mine. I was just reading about Brad Thor, a thriller writer, who was sitting next to a woman on a plane with whom he got talking literature. Toward the end of the flight, he mentioned he was thinking about writing a novel. She told him she was a salesrepresentative of Simon and Schuster, and she’d like to read his manuscript when he was done with it. He did send it to her and it got published by Simon & Schuster, and now he’s making big bucks. I can just see you or me having a conversation with the sales rep. . . .

Oh, and the book I spoke of hoping to write on the last hundred years or so of American poetry would not be a manifesto. The changes I want are very limited: only that the Poetry Establishment notice my kind of poetry—even if they trash it. And that a poet should do his best to master every kind of poetry he can during a lengthy apprenticeship; then focus on his favorite kind, but keep in touch with as many of the other kinds as he can. Too many “advanced” poets are as foolishly indifferent to traditional poetry, particularly formal verse, as traditional poets are to visual poetry and the like.

I thought I had a third demand of the poetry world, but can’t think of it now.

You have me there, Jerry. But it’s as much a problem with the language as with me. I was bringing up my standard belief in the difference I find between “effective” poems and “important” poems. I need different words. My point is simply that even great poems as the one by Hass you mention may be do not significantly enlarge the field of poetry because they add nothing significantly new to it. They will add a new outlook and style, since every poet has a unique outlook and style, and perhaps new subject matter. But new subject just doesn’t seem significant to me. One painter is the first to depict some new species of butterfly, so what? Or a novelist is first to tell us what the life of an Australian aborigine juggler is like. Ditto.

I think the best examples of what I mean are in classical music: I think a case could be made for the view that Brahms’s symphonies equal in effectiveness to Beethoven’s, but Beethoven’s were far more important than Brahms’s. I prefer Richard Straus’s Der Rosenkavalier to any of Wagner’s operas (I think) but Wagner’s operas are unquestionably more important in the way I’m speaking of than Straus’s. Wagner and Beethoven advance their art, Brahms and Straus did not, they “merely” contributed brilliantly to it.

I’ll let you know when I have the right two words or phrases needed to distinguish the two kinds of artists.

l suspect he made use of haiku, too. But however effective you do a good job of showing he was, he wasn’t “significant” in my special sense.

best, Bob

.

Entry 833 — Plot Versus Character

Friday, August 17th, 2012

Yesterday I finished reading Tom Clancy’s The Hunt for Red October. It’s a mere “genre” novel, but I doubt any of the “art” novels of our time are better. I think critics have too long been under the influence of Henry James, whose forte was characterization, not plot, as Clancy’s is. I much prefer The Hunt for Red October to the one James novel I know I read, The Ambassadors–a penetrating psychological study of an absolute nincompoop as far as I’m concerned. The inability to be explicit does not seem the brilliant virtue to me it does to Jamesians.

I think taste in these matters boils down to which of a person’s awarenesses is stronger, his sagaceptual awareness or his anthroceptual awareness. I’ve discussed all this before, but haven’t anything else to post today, so here it is again. (I also want to make public my notion of sagaceptuality as much as possible so maybe I’ll get some credit for it when some certified theoretical psychologist discovers it.) It’s the awareness which tends to organize thinking in goal directed modes–i.e., to put a person on a quest. It could be a child hunting for pirate treasure on a beach, a girl pursuing a boy, me working up a decent definition of . . . “sagaceptuality.” It could also be a vicarious quest, as was the one I went on with the hero of The Hunt for Red October. With several of the heroes of that book, actually.

What happens is that we all have an instinctive recognition of certain goals–for instance, the capture of a mate. We usually have some instinctive goal pursuit drive that the object we recognize as a proper goal makes available to us. What it does, basically, is lock us onto the object it is our goal to capture (or escape from) and energize us when we are effectively closing in on it (or escaping it), and de-energize us to take us out of single-minded ineffective pursuit and expose us to other possible better kinds, until one of them is judged to improve out pursuit. In other words, just a homing device, with many different possible targets, like a possible mate, or food, or beauty, or fame. Nothing much to it.

Anthroceptuality is simply interest in oneself and others. When it is dominant, other instincts rule us, such as the need for social approval. Needless to say, both anthroceptuality and sagaceptuality will usually be in some kind of partnership–with other awarenesses. But some, as I’ve said, will be stronger in sagaceptuality than anthroceptuality, and some the reverse. The former will prefer plot in the stories he reads or movies he watches to characterization; the latter will consider plot trivial compared to characterization. I’m convinced that normal men are sagaceptuals, normal women anthroceptuals. But not necessarily all the time.

.

Entry 811 — Monet & Minor News and Thoughts

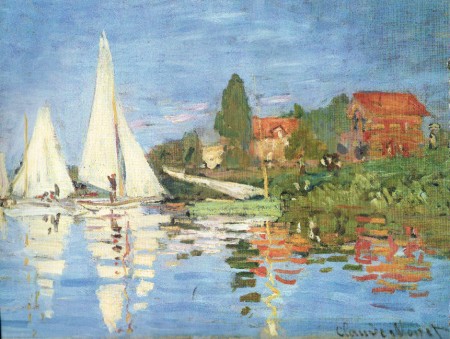

Thursday, July 26th, 2012

Below is Monet’s Regatta at Argenteuil. It’s from a calendar I’ve had hanging in my computer room for several years because I like it so much. I now have a second interest in it: using it in one of my long division poems. I want to do that because of an event the local visual arts center I belong to (which has a building where it has classes and puts on exhibitions, one of them a yearly national one, albeit none of them are what anyone would call close to the cutting edge) is sponsoring. Many of its painters are painting copies of Monet works, and poets have been invited to submit poems about Monet works to be show with the paintings. There is probably a reading, too. I thought it would be amusing to submit one of my poems, and I’d love to be able to use Regatta at Argenteuil. I have another couple of months I’ve just found out. I thought I needed to get it done by August. Which is why I scanned my copy of the painting a while ago, making it available for this entry, one more that I had nothing much else for.

.

I can’t think of anything to go with the painting. I haven’t had very few ideas for the past three or four months, and none I was interested in to do more than jot down somewhere. Last years bout this time I found out about a contest the magazine Rattle has every year. One can submit up to 4 poems to it, and I knew it had published some visual poems at one time, so was inspired to make a set of four long division poems for the contest, four that I still think are among my best. They never arrived because I didn’t put enough stamps on the envelope I sent them in, unaware of the latest cost of sending. I wish I could try again–this deadline is 1 August–but no ideas. And the poems have to be unpublished. I should be saving poems for contests, especially for one like this that I know will occur yearly, but I tend either to post them here, or send them to the latest editors who have invited work from me. Another problem for me is that I’m often unsure whether or not a particular poem of mine has appeared anywhere. The main problem, of course, is that I’m so unprolific. I could do a bunch of Poem poems at just about any time, I think, but I don’t consider them good for contests because so dependent on my main character, whom I believe hard to take to until exposed to a number of times. If even then.

Entry 785 — the Otherstream and the Universities

Saturday, June 30th, 2012

As I said in another entry, Jake Berry has an article in The Argotist Online, edited by by Jeffrey Side, that’s about the extremely small attention academia pays to Otherstream poetry you can read here. I and these others wrote responses to it: Ivan Arguelles, Anny Ballardini, Michael Basinski, John M. Bennett, John Bradley, Norman Finkelstein, Jack Foley, Bill Freind, Bill Lavender, Alan May, Carter Monroe, Marjorie Perloff, Dale Smith, Sue Brannan Walker, Henry Weinfield. A table of contents of the responses is here. I hope eventually to discuss these responses in an essay I’ve started but lately found too many ways to get side-tracked from. The existence of the article and the responses to it has been fairly widely announced on the Internet. Jeff Side says they’ve drawn a lot of visitors to The Argotist Online, ” 23,000 visitors, 18,000 of which have viewed it for more than an hour.” What puzzles both him and me is that so far as we know, almost no one has responded to either the article or the responses to the article. There’s also a post-article interview of Jake that no one’s said anything about that I know of. Why?

What we’re most interested in is why no academics have defended academia from Jake’s criticism of it. Marjorie Perloff was (I believe) the only pure academic to respond to his article, although Jeff invited others to. And no academic I know of has so much as noted the existence of article and responses. I find this a fascinating example of the way the universities prevent the status quo from significantly changing in the arts, as for some fifty years they’ve prevented the American status quo in poetry from significantly changing. Here’s one possible albeit polemical and no doubt exaggerated (and not especially original) explanation for the situation:

Most academics are conformists simply incapable of significantly exploring beyond what they were taught about poetry as students, so lead an intellectual life almost guaranteed to keep them from finding out how ignorant they are of the Full contemporary poetry continuum–they read only magazines guaranteed rarely to publish any kind of poetry they’re unfamiliar with, and just about never reviewing or even mentioning other kinds of poetry. They only read published collections of poems published by university or commercial (i.e. status quo) presses and visit websites sponsored by their magazines and by universities. Hence, these academics come sincerely to believe that Wilshberia, the current mainstream in poetry, includes every kind of worthwhile poetry.

When they encounter evidence that it isn’t such as The Argotist Online’s discussion of academia and the otherstream, several things may happen:

1. the brave ones, like Marjorie Perloff, may actually contest the brief against academia–albeit not very well, as I have shown in a paper I will eventually post somewhere or other;

2. others drawn in by the participation of Perloff may just skim, find flaws in the assertions and arguments of the otherstreamers, and there certainly are some, and leave, satisfied that they’ve been right all along about the otherstream;

3. a few may give some or all the discussion an honest read and investigate otherstream poetry, and join the others satisfied they’ve been right all along, but with better reason since they will have actually investigated it; the problem here is that they won’t have a sufficient amount of what I call accommodance for the ability to basically turn off the critical (academic) mechanisms of their minds to let new ways of poetry make themselves at home in their minds. In other words, they simply won’t have the ability to deal with the new in poetry.

4. many will stay completely away from such a discussion, realizing from what those written of in 1., 2. and 3 tell them. that it’s not for them.

A major question remains: why don’t those described in 2. and 3. comment on their experiences, letting us know why they think they’ve been right all along. That they do not suggests they unconsciously realize how wrong they may be and don’t want to take a chance of revealing it; or, to be fair, that they consider the otherstream too bereft of value for them to waste time critiquing. This is stupid; pointing out what’s wrong with bad art is as valuable as pointing out what’s right with good art. Of course, there are financial reasons to consider: a critique of art the Establishment is uninterested in will not be anywhere near as likely to get published, or count much toward tenure or post-tenure repute if published as another treatise on Milton or Keats. Or Ashbery, one of the few slightly innovative contemporary poets of Wilshberia.

But I think, too, that there are academics who unconsciously or even consciously fear giving any publicity at all to visual or sound or performance and any other kind of otherstream poetry because it might overcome Wilshberia and cost them students, invitations to lecture and the like–and/or just make them feel uncomfortably ignorant because incapable of assimilating it. Even more, it would cost them stature: it would become obvious to all but their closest admirers that they did not know all there is to know about poetry.

Note: I consider this a first draft and almost certainly incomplete. Comments are nonetheless welcome.

.

Entry 730 — Establishment Poetry Anthologies

Sunday, May 6th, 2012

When mediocrities protest an anthology of poems, they invariably complain about some fellow mediocrity’s being left out. When I protest an anthology of poetry, I complain about entire schools of poetry being left out. A less common complaint of academic mediocrities about anthologies is that their publishers were too cheap to pay to republish some canonized work already published elsewhere ten or twenty times, like “The Wasteland.” I say no anthology that has to pay for permission to publish any poem in it is worth reading, because the only poems we need an anthology for are by poets whose superiority to what’s in anthologies like Dove’s makes them ineligible to qualify for payment for their work.

Wouldn’t it be nice for mediocrities, though, if we had a hundred anthologies and they ALL had “The Wasteland” in it—assuming, of course, that they had no equivalent from our time of that poem, but that goes without saying.

If the poetry establishment had a choice between an anthology with nothing but the best Amercian poems composed before 1950 and an anthology with no poems published before 1950 or any innovative poems published after 1950, which would it choose? Generally, establishment anthologies try to combine the two.

.