Archive for the ‘Literary Criticism’ Category

Entry 440 — Support for My Hyperneologization

Saturday, May 7th, 2011

.

I came across it by chance:

APODIZATION* literally means “removing the foot”. It is the

technical term for changing the shape of a mathematical function, an

electrical signal, an optical transmission or a mechanical structure.

An example of apodization is the use of the Hann window in the Fast

Fourier transform analyzer to smooth the discontinuities at the

beginning and end of the sampled time record.

Now, then, is this a pompous, unpronounceable, superfluous term? It was once a coinage, you know. Why not “foot-removal?” I suspect because whoever coined it wanted it quickly to narrow the mind into mathematics, i.e., a particular system or discipline–which I also want most of my terms though not “Wilshberia” to do. I know: there’s a difference between a certified subject like mathematics and the theoretical psychology I try to link my terms to. I understandably (I should think) don’t consider that relevant. Why should someone be discouraged from systematic naming of terms to fit interactingly into a theory he’s creating just because he’s a crank.

I think one reason for my lack of recognition is that the sort of people who might be in sympathy with my hyperneologization are not generally the sort of people with an interest in poetics. As I’ve often declared, I may well be too much of an abstract thinker to be a poet and too much of an intuitive thinker to be a scientist. You’d think that would help me with both groups but it does the opposite. About the only “real” mathematician who appreciates my mathematical poems is JoAnne Growney.

The other day, after my “anthrocentricity’ and “verosophy” had been subjected to the usual reactionary jibes, I asked why “egocentricity” was an acceptable word for “self-centeredness,” but “anthrocentricity” not an acceptable word for “people-centeredness.” Needless to say, no one answered me.

Far too many many academics are so locked into their received understandings that they are blind to how those understandings might be revised or extended in ways that require the coinage of new terms.

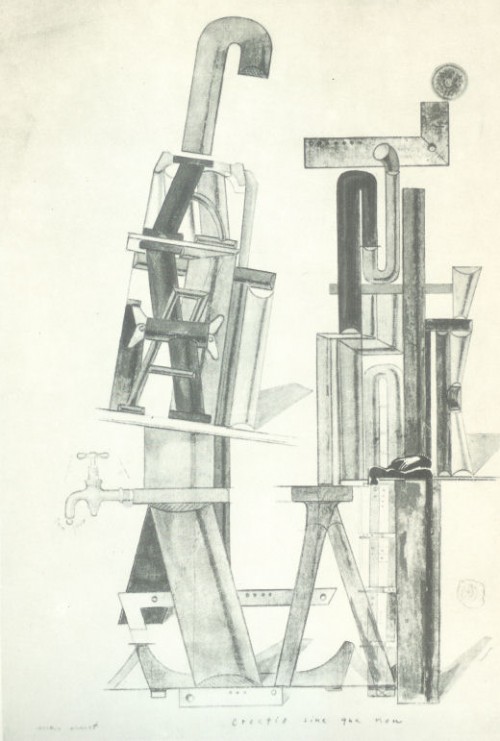

Entry 439 — A Textual Design by Max Ernst

Thursday, May 5th, 2011

.

This is Erectio sine qua non, by Max Ernst, 1919. I copied it out of Surrealst Drawings, with text by Frantisek Smejkal. I view it as letters taking shape, with other forms, to eventually result in an erection that can be taken to be “meaning” formed of language. Other interpretations of equal validity can be made. Although I made out two words under the faucet, they seem to me much to minor to make this pice a visual poem. Nor, of course, does the book it’s in call it that. Remember, kids, as Uncle Bob keeps telling you, a word should always mean something, but it should always indicate something that it isn’t, or it’s useless. So, if you want to call this neato visimage a visual poem, fine–but Uncle Bob, and maybe one or two other people, will want to know what isn’t a visual poem.

Entry 438 — Fun with the Nullinguists

Thursday, May 5th, 2011

And just one more language note, since we are poets and poetry readers. . .

Unlike many academics, bureaucrats, or military officials, I don’t think it’s necessary to invent pompous, unpronounceable and superfluous synonyms for simple terms that already exist. At best it’s comic relief. At worst, well, see George Orwell. . . . About the only one of good old Bob’s prolific stream of coinages that strikes me as worth keeping is “burstnorm.” That actually does improve on the other available words, seems to me, and has the advantage of simplicity and poetic power.

–David Graham

Okay, David, tell me what’s wrong with “infraverbal poetry”

–Bob

A guess, “Bob” (& I didn’t even take any pills!) –

M: rigid, defensive tribal and national identities, ungiving hierarchical principles, concentrated authority, reflexive aggression in a repetition compulsion that overrides desires for peace …

–Amy King

Thanks, Amy. It’s good for my morale to know you can’t find anything of consequence wrong with my term.

But this may be a fate not worse than the memento mori of the progeny of Aristotelian logic which remain eternally fixed in delusions of universal absolutes and therefore empty of useful meaning. To wit, Wittgenstein’s remark, “But in fact all propositions of logic say the same thing, to wit nothing…”

–Amy King

Spoken like a true absolutist. Nothing to do with me, though, for I believe in maxilutism, the belief that while no absolutes exist (except in logic and mathematics, I now realize), many maxilutes, or understandings close enough to absolutely true to be treated as absolutes, do exist.

–Bob

* * * * * * *

This kind of nullinguistics is not entirely worthless: when Professor Graham later said “misspelled poetry” was what “infraverbal poetry” should be called, it made me say why he was wrong: “‘Misspelled poetry’ clearly doesn’t work. For one thing it does not indicate whether the misspelling is intended or not. Another is that ‘misspelledly’ doesn’t work very well (I don’t think) as an adverb. Probably most important, there are many examples of infraverbal poems that have much more going on inside them than what most people would think of as misspellings–a letter on its side, for instance. Actually, some infraverbal words are correctly spelled. ‘Misspelling,’ for instance–which I just made up and is certainly not much of an infraverbal poem but is one.” I count the realization that infraverbal words can be correctly spelled a nice addition to my knowledge of them.

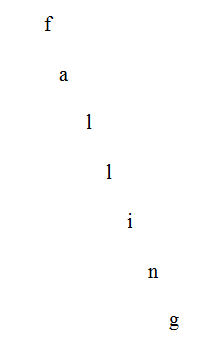

Entry 436 — Visual Poetry Intro 1a

Tuesday, May 3rd, 2011

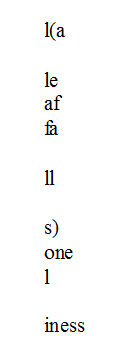

According to Billy Collins, E. E. Cummings is, in large part, responsible for the multitude of k-12 poems about leaves or snow

But, guess what, involvement in visual poetry has to begin somewhere. Beyond that, this particular somewhere, properly appreciated, is a wonderful where to begin at. Just consider what is going on when a child first encounters, or–better–makes this poem: suddenly his mindflow splits in two, one half continuing to read, the other watching what he’s reading descend. For a short while he is thus simultaneously in two parts of his brain, his reading center and visual awareness. That is, the simple falling letters have put him in the Manywhere-at-Once I claim is the most valuable thing a poem can take one to.

To a jaundiced adult who no longer remembers the thrill letters doing something visual can be, as he no longer remembers the thrill the first rhymes he heard were, that may not mean much. But to those lucky enough to have been able to use the experience as a basis for eventually appreciating adult visual poetry, it’s a different story. Some of those who haven’t may never be able to, for it would appear that some people can’t experience anything in two parts of their brains at once, just as there are people like me who lack the taste buds required to appreciate different varieties of wine. I’m sure there are others who have never enjoyed visual poetry simply because they’ve never made any effort to. It is those this essay is aimed at, with the hope it will change their minds about the art.

I need to add, I suppose, that my notion that a person encountering a successful visual poem will end up in two significantly separate portions of his brain is only my theory. It may well be that it could be tested if the scanning technology is sophisticated enough–and the technicians doing the testing know enough about visual poetry to use the right poems, and the subjects haven’t become immune to the visual effects of the poems due to having seen them too often. Certainly, eventually my theory will be testable.

The following poem by Cummings, which is a famous variation on the falling letters device, should help them:

But Cummings uses the device much more subtly and complicatedly– one reads it slowly, back and forth as well as down, without comprehending it at once. Cummings doesn’t just show us the leaf, either, he uses it to portray loneliness. For later reading/watchings we have the fun of the three versions of one-ness at the end and the af/fa flip earlier–after the one that starts the poem.

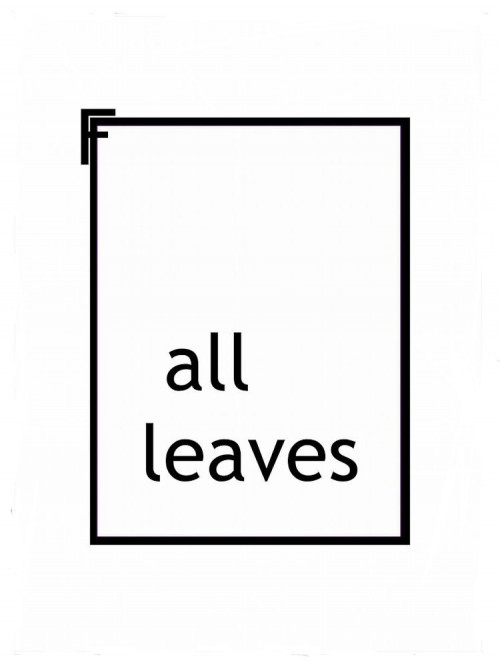

Marton Koppany returns to the same simple falling leaf idea but makes it new with:

In this poem the F suggests to me a tree thrust almost entirely out of Significant Reality, which has become “all leaves”–framed, I might add, to emphasize the point. So: as soon as we begin reading, our reading becomes a viewing of a frame followed quickly by the sight of the path now fallen leaves have taken simultaneously with our resumed reading of the text. Which ends with a wondrous conceptual indication of “the all” that those leaves archetypally are in the life of the earth, and in our own lives. And that the tree, their mother and relinquisher, has been. Finally, it is evident that we are witnessing that ” all” in the process of leaving . . . to empty the world. In short, the archetypal magnitude of one of the four seasons has been captured with almost maximal succinctness.

So endeth lesson number one in this lecture on Why Visual Poetry is a Good Thing.

Note: I need to add, I suppose, that my notion that a person encountering a successful visual poem will end up in two significantly separate portions of his brain is only my theory. It may well be that it could be tested if the brain- scanning technology is sophisticated enough–and the technicians doing the testing use the right poems, and the subjects haven’t become immune to the visual effects of the poems due to having seen them too often. Certainly, eventually my theory will be testable.

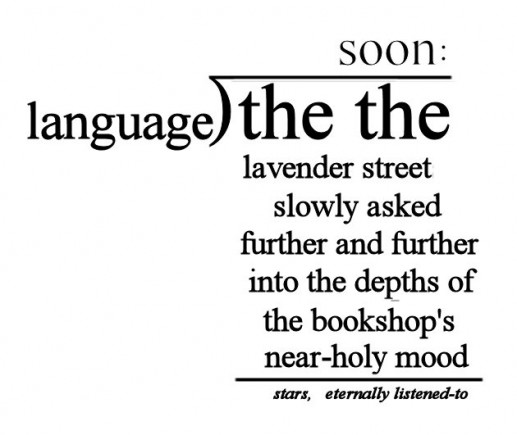

Entry 372 — Mathemaku Still in Progress

Tuesday, February 8th, 2011

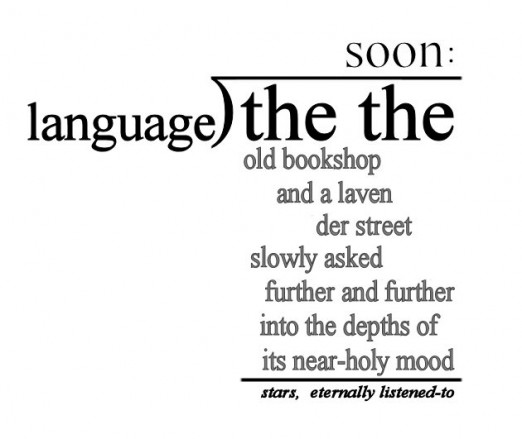

If I ever come to be seen worth wide critical attention as a poet, I should be easy to write about, locked into so few flourishes as I am, such as “the the” and–now in this piece, Basho’s “old pond.” I was wondering whether I should go with “the bookshop’s mood or “a bookshop’s mood” when Basho struck. I love it!

If I ever come to be seen worth wide critical attention as a poet, I should be easy to write about, locked into so few flourishes as I am, such as “the the” and–now in this piece, Basho’s “old pond.” I was wondering whether I should go with “the bookshop’s mood or “a bookshop’s mood” when Basho struck. I love it!

Just one word and a trivial re-arrangement of words, but I consider it major. (At times like this I truly truly don’t care that how much less the world’s opinion of my work is than mine.)

We must add another allusion to my technalysis of this poem, describing it as solidifying the poem’s unifying principal (and archetypality), Basho’s “old pond” being, for one thing, a juxtaphor for eternity. Strengthening its haiku-tone, as well. But mainly (I hope) making the mood presented (and the mood built) a pond. Water, quietude, sounds of nature . . .

Oh, “old” gives the poem another euphony/assonance, too.

It also now has a bit of ornamental pond-color. Although the letters of the sub-dividend product are a much lighter gray on my other computer than they are on this one, the one I use to view my blog.

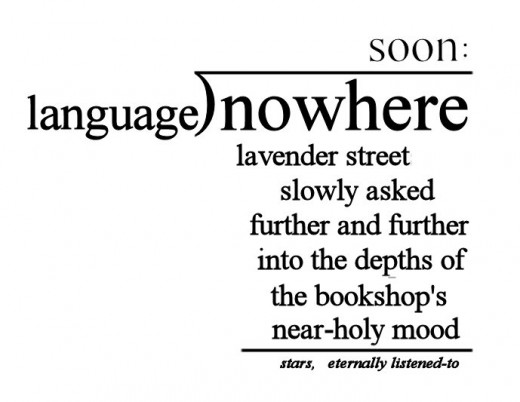

Entry 371 — My New Mathemaku, Updated

Monday, February 7th, 2011

Updated, but probably not finished, although I consider the dividend set:

Now to my pluraphrase of this poem I have to add that the dividend is a quotation from Wallace Stevens’s “On the Dump,” one of my all-time favorite poems, so brings that poem’s concern with the nature of metaphor, (sensual) fascination with the seasons and the final essence of existence to it. It’s another fresh expression, too, because still a shock to most minds, and certainly unexpected in this poem. It also provides the poem, I think, with a unifying principle, the idea of language’s being on the precipice or “soon” to (“:”) bring one to the the making, at least to me, enough sense for a poem.

Incidentally, one thing a pluraphrase should do that I neglected to mention is determine a poem’s level of archetypality. Mine seems to me, with “the the” now in it, to do that at the highest level with the search for the meaning of existence. Stars are archetypal. The struggle to express oneself seems to me moderately archetypal.

Entry 370 — A New Mathemaku

Sunday, February 6th, 2011

It’ll be “Mathemaku Something-or-Other” when I figure out how many mathemaku I’ve now composed. Close to a hundred, I’m sure.

Frankly, I don’t know what to make of this. Whether I keep it or not will depend on what others say about it. I made it as an improvisation using “soon:,” so as not to lose the latter due to my revision of the poem it was in. The sub-dividend product is a fragment of my standard Poem poem semi-automatic imagerying.

It is, in fact, a near-perfect candidate for a pluraphrase. Which I’ll add later today.

* * * * *

Okay, here’s my pluraphrase (with thanks to Conrad Didiodato, whom made a comment to my entry for yesterday that I ought to “flesh out” my description of the pluraphrase by demonstrating its operation on some classical poem. That didn’t appeal to me, classical poems having been more than sufficiently discussed, but doing it for a poem I’d just been working on did. It ought to test as well as demonstrate the procedure–and maybe help me with my poem, which it may well have, it turns out. Time to start it.

After a note to the fore: what follows is to be taken as an attempt, an intelligent attempt, to prove a definitive pluraphrase of the poem treated, not a claim to do so.

1. According to this poem, if you divide “nowhere” by “language,” you’ll get “soon:,” with a remainder of “stars, eternally listened-to.” The poem also indicates that multiplying “language” by “soon:” equals “lavender streets slowly asked further and further into the depths of the bookshop’s near-holy mood.”

2. “soon” is an adjective indicating an event that has not yet occurred, a what-will-happen in the near future. An expectation of something interesting to come is thus connoted, a connotation emphasized by the use of the colon, a punctuation mark indicating something to follow. “Language” is the main human means of expression, communicated expression, so the metaphor, “language” times “soon:” suggests some sort message of consequence that is on the threshold of appearing. The arithmetic of the poem equates this message-to-come with “lavender streets,” or a path not likely to be real because of its color so a fairyland or dream path–through a town or city because a “street,” which has urban connotations, and because entering in some way a bookshop’s mood, which places it in a center of trade.

The street does not go in the mood but is “slowly asked” into it, “asked” serving as a metaphor for “go.” We are not told who or what is doing the asking, ever. A feature of many of the best poems is details left to puzzle the reader into subjective but potentially intriguing never quite sure answers. For instance, that here the draw of the books in the shop is strong enough to invite a street, and those on it, into the shop. It’s subtle, though, or so its slowness suggests. And a production is being made of the asking, since ordinarily to ask something takes but a moment. It’s important.

The personification of the bookshop as a creature capable of experiencing a mood clearly makes “mood” a metaphor” for “ambiance.” This ambiance is “near-holy” for some unspecified reason, probably having something to do with language, books, literature, the word. Something complex since the street apparently goes quite deeply into the mood–and, as I’ve just pointed out, slowly. With perhaps deliberation. Not on whim.

In keeping with “soonness,” the street reaches no final point, it is in the process of going somewhere. Something is building.

If “stars, eternally listened-to” is added (and the addition needn’t be metaphors since additions are not confined to mathematics) to the image of the street descending into the bookshop (or bookshop’s “mood”), we somehow get “nowhere.” Or so the arithmetic requires us to accept. Stars are (effectually, for human beings) eternal, and ‘listened-to” must be a metaphor for attended to or the like. Or a reference to the music of the spheres, making what’s going on a mystically experience. It would seem to be intended to be awe-

inspiring. Hence, for it to contribute, with a perhaps questing street, perhaps questioning street, to nowhere seems a severe anticlimax, or a joke. Nothing makes sense except that the view expressed is that our greatest efforts lead nowhere. Which I don’t like. If I can improve the poem, from my point of view, by changing the dividend, which I may well do, it will demonstrate the value for a poet of a close reading of his work.

My pluraphrase is far from finished, though. We have the technalysis to get through–and, in passing, I have to say that that is a beautiful term, I must say, even if no one but I will ever use it. Melodation? Well, the euphony of “nowhere,” “slowly,” “holy,” “soon:,” “into,” “shop’s” “mood,” “to” and “star,” with the first two carrying off an assonance, and the long-u ones possibly assonant with each other, too. The “uhr”-rhymes, and backward rhyme of “lang” with “lav.” A few instances of assonance, alliteration and consonance, but no more than you’d get in a prose passage of comparable length. I would say that the pleasant sound of the sub-dividend product’s text adds nicely to its fairy-flow, but that melodation is not important in the poem. No visio-aesthetic effects are present, or anything else unusual except, obviously, the matheasthetic effects.

The mpoem’s being in the form of a long division example, the chief of these, allow the metaphors of multiplication and addition already described in the close reading–but also the over-all metaphor of a “long-division machine” chugging along to produce the full meaning of the poem. This provides a tone of inevitability, of certainty, of this is the way things truly are. The ambiance of mathematics caused by the remainder line, and what I call the dividend-shed, is in what should be a stimulating tension with the ambience of the poem’s verbal appearance–as a poem. Extreme abstraction versus the concreteness of the poetic details, science versus art, reason versus intuition. All of which makes an enormous contribution to the poem’s freshness, since very few poems are mathematical.

The final function of an artwork is to cause a person to experience the familiar unexpectedly, here with long division yielding an emotional image-complex some engagents of the poem will find familiar. Too much unfamiliarity for those without some experience of poems like this one. Which reminds me that since this poem has a standard form, at least for this poet’s work, a long-division example–and, more generally, an equation, it alludes to other poems of its kind. No other allusions seem present.

Part of the poem’s freshification, too, are “lavender street” since few streets are lavender, the idea of a street’s being “asked” into something, the idea of stars as “listened-to,” or a bookshop’s having a mood. The breaking up of the poem into five discrete images is easy enough to follow but different enough to be fresh.

That’s it for the pluraphrase. I think I’ll make the dividend “the the.” The only thing I have against that is that I’ve used that before more than once. I’ll probably do more with the look of the thing, add colors. I’ve had thoughts from the beginning of giving it a background, with words.

Entry 369 — A Discussion of the Pluraphrase

Saturday, February 5th, 2011

In his kind blog entry on me the other day, Geof Huth pointed out a difference between the two of us that got me thinking. It was that I need to know the meaning of each of my poems, whereas he doesn’t mind not knowing what a particular poem of his means, and sometimes doesn’t. As is often the case, he was half right. Certainly, I have a greater need to know the meaning of my poems than he has to know the meaning of his. Never do I expect fully to know the meaning of a poem of mine, however. Indeed, if I too quickly maxolutely grasp a poem’s meaning, I feel pretty certain it isn’t very good.

If by “understanding the meaning” we mean understanding the verbal meaning. I mean far more than that by the term, though, for one can have only a very hazy verbal understanding of some poems but a visceral understanding of them that more than makes up for it. Which I suspect Geof needs. Does a poem make sense as an arrangement of elements? Does it sound or look aesthetically pleasing in some important manner?

Zogwog. I played tennis this morning. On the way back on my bike I thought of how I was going to soar through this entry. I had what I was going to say all figured out. The result would be a description of something I call “the pluraphrase,” that I came up with twenty years or so ago. It’s basically an analysis of a poem so full that, if carried out with skill, should permanently nail a poem. I think no poem can be considered effective if no one can come up with a pluraphrase of it a reasonable number of others agree is sound and reasonably complete. Effective as a poem, I mean.

For some reason, I’m swigging every whose where, not sure why. Will try to get a grip on mineself and concentrate.

First there’s the paraphrase, which is a summary of what the poem’s words and graphics, if any, mainly denote, connote and clearly allude to via quotations, symbols or other “advertances,” as I call them. If you can’t make one for a given poem, either you or it is defective. But there is much more to a poem than what a paraphrase tells you about it.

One thing is what a close reading uncovers. Which should be everything a poem’s words and graphics, if any, denote, connote and allude to.

Finally, and in my view most important, is the pluraphrase. That’s the close reading plus the . . . technalysis, my new-today term for an analysis of what a poem does technically. To wit: its melodation, or everything regarding what it does with sound–rhyme, meter, auditory shaping–and anything that contributes to the poem’s connotational or allusional ability (which can be great–for instance, what the sonnet-shape does as an advertance to the history of the sonnet in the West); its visio-aesthetic effects, or what its visual elements beyond the conventional shape of its letters, punctuation marks and other textemes do for it decoratively or visiopoetically; its audio-aesthetic effects, or what its auditory elements beyond the conventional sound of its syllables do for it decoratively or beyond that to make it a sound poem, if that’s what it is; its linguitechnics or its appropriate misuse of grammar for aesthetically meaningful language poetry effects; its freshification (I know, I need a better term for this, but I’m ad hoccing at the moment), which in conventional poetry is primarily its use of fresh diction or subject matter–particularly in the case of surrealistic and jump-cut poetry, of fresh juxtapositions of images; mathaesthetic effects, or the use of mathematical operations on non-mathematical terms as in my mathemaku; miscaesthetic (miscellaneous aesthetic) effects or the contribution of its gustatory, olfactory, tactile, or the like in some aesthetically meaningful way.

No doubt there are elements of poetry I’ve overlooked. Let me know about them, please. I truly want to be complete.

My view, as stated, is that no poem that cannot be given a reasonably full and coherent pluraphrase can be effective. My only evaluative uncertainty is whether or not a poem for which no reasonably full and coherent close reading exists can be considered effective–as a poem. Such a text may prove sufficiently audio-aesthetically or visio-aesthetically pleasing to be considered effective as music (textual music) or visimagery (textual visimagery), but not as poetry, which needs to be verbo-aesthetically compelling to qualify as an effective poem. For instance, Gertrude Stein’s buttons, which are not poems but short pieces of evocature, would be effective as prose if they could be shown to make verbal sense. Stephen-Paul Martin did that for one of them to my satisfaction in a book whose title escapes me, and someone else did the same for another, I vaguely recall. Marjory Perloff failed to do it for a number of them. As is, the most you can say for them is that they may be somewhat effective pieces of music.

Getting back to how much a poet should know about his own poems, I don’t think he ought to make a pluraphrase of everyone of them. I haven’t of mine. But he ought to have some feel for whether a poem of his could be pluraphrased, and whether at least some of its elements were superior. I’m sure that most poets know these things in some way. Sometimes intense analysis is necessary, I think. Unless a single pleasing effect is enough for you, and you don’t care about the unifying principle I believe every poem needs to make it to the top.

My temperament is such that I enjoy analysis. I find it almost always useful. True, sometimes one’s analysis can lead one astry. More often it helps, I believe. I now believe it has with regard to the mathemaku Geof posted of mine in his little celebration of my birthday the other day. The version he posted almost convinced me I should have “soon:” as its quotient instead of “Persephone.” Last night, thanks to analysis, to trying to fathom the full meaning of the poem, I concluded I was wrong. “Persephone” is definitely better. The quotient times “mystery” is supposed to equal the springlike effect of language on the world, according to my analysis, so multiplying it by “Persephone,” the goddess of spring, will clearly allow this while multiplying it by “soon:” will not clearly do it. The idea of soon something will follow won’t suggest it to many, I don’t think. And although I tried hard to think of how language could be thought to have anything to do with “soonness,” I couldn’t. Nor did mystery. If it had, then “soon:” wouldn’t have had to. “Persephone” may be a tick too overt, but I’d rather be too clear than unclear. Besides, it’s “Persephone” in its sole hard copy publication.

* * *

On my bike, I imagined I’d be able to make this entry a wonderful source for students of poetry that no college could be without. It didn’t work out that way. I do hope to return to it sometime and improve it.

Entry 337 — A Quotation from Karl Young

Wednesday, January 5th, 2011

I just happened on the following passage from Karl Young’s introduction at Light and Dust to his two early books, Cried and Measured, and Should Sun Forever Shine. I had to post it here because it so exactly states what I’ve been saying for many years, with little effect, except occasionally to inspire hostile responses from the anti-intellectual school of the Wordsworthian “We murder to dissect” variety.

“How best to provide the (engagent of unfamiliar, relatively new forms of art) with adequate context and background, I don’t know. I do know that the lack of it has crippled visual poetry, as it has other arts, and trying to find an answer to the problem is one of the reasons for writing essays like this one. Whatever the case, in the global world of information overload, the concept that ‘the work speaks for itself’ can be no more than nostalgia for a simpler time with a unified and unchanging cultural background. In the broadest context, what has now become the superstition that avant-garde work can be appreciated without context denies and blocks the possibilities of cooperative construction and understanding in an environment that no individual has the ability to completely comprehend, but which requires cooperation to appreciate.”

. Karl Young

Entry 334 — One Reason I’m Not a Fan of Emily’s

Monday, January 3rd, 2011

A major problem I have with Emily Dickinson’s pieces is that they seem to me much more rhymed opinions than poems.

The reason people who eat lots of vegetables live longer than those who don’t is that they live much more slowly and non-productively.

Yes, another get-it-quickly-out-of-the-way entry. I have a better than usual excuse, though: one of my teeth crumbled a week or so ago and the crown that was on it came off. I couldn’t see my dentist till today because her office was closed for ten days for the holidays. Today I saw her and found out that the tooth was too far gone for the crown to be re-cemented to it, as it had been twice during the past six months. So the remains of the bad tooth were extracted. That was six hours ago. I’ve taken an idoprofen and it’s not bothering me, but I’m very tired. I’m also unhappy because the cost of what next needs to be done, which will involve a crown and a false tooth, will cost me two grand, and I’m already scheduled for a crown that will cost me $1,300.

Oh, well, on the bright side, last night in bed I worked out three more mathemaku, one completely done, the other two close enough to being done that I’m sure they will be. And just a little while ago I sketched another that I may complete this evening. Needless to say, I’m pleased. I don’t think I’ve had a creative outburst like this for two years. Certainly I didn’t in the year just past. Not that it’s all that amazing, as all six of the new mathemaku are inter-related, and share components, and the main graphic–the only graphic I’ve used so far–is an old graphic of mine, re-cycled. (And it is a re-cycled version of my first large-scale abstract-expressionist visual poem, executed fifteen or more years ago.)