Archive for the ‘Literary Criticism’ Category

Entry 1645 — Part of Something from 1994

Friday, November 28th, 2014

I was going to write something new for today but it fell apart somewhere before its midpoint. I have hopes for it, but . . .

So, in place of it, here’s commentary on poetry from an article published twenty years ago that I actually got paid for: 9 pages on all the neglected kinds of poetry then extant (just about all of which are still extant, and neglected). As is the case with nearly all my poetry commentary/criticism, no one every wrote me about it.

I was going to use just what I said about Kathy Ernst’s “Philosophy,” then thought it might be interesting to present the whole page in media res. Less work for me, at any rate. So, here is page 6 from the November/ December issue of Teachers & Writers:

Entry 1453 — One of My Best SPR Columns

Tuesday, August 19th, 2014

When Marilyn emailed me about the publishworthiness of her bookwork, she mentioned that I had reviewed the page I reproduced here yesterday in an old Small Press Review column. Wondering what I’d said, I looked it up (it’s in this blog’s “Pages” to the right), and like it well enough to post it here.

A New Vizlature AnthologySmall Press Review, Volume 29, Number 2, February 1997 Visuelle Poesie aus den USA, edited by Hartmut Andryczuk. 67 pp; 1995; Pa; Hartmut Andryczuk, Postlagernd D-12154, Berlin, Germany Toward the end of 1995 a new anthology of vizlature, or verbo-visual art, came out of Germany. It was edited by Hartmut Andryczuk. I was sent a copy of it because I have a couple of pieces in it, but–alas–I got no details concerning its price. Among the sixteen participants in Andryczuk’s anthology is Marilyn R. Rosenberg, quietly one of this country’s premiere vizlateurs for some two decades. She is represented by a landscape-sketch close enough to an outline to double as a map, thus exploiting the tension of the literal versus the abstract. Her piece is all in calligraphic lines of various degrees of thickness and delicacy that delineate clouds (or mountains) forming above water foaming into being among juts of a landmass. The latter includes an area that could be either a tilled field or a lined page, but in either case is a locus of creativity. At various points in the composition are a Q, and an A (to suggest question/answer), three X’s, a C and a T–and, right together, a W, an upside-down W (or M), and a sideways W (or E), to put us in a Japanese-serene country where a breeze can tilt West to East, and all hovers mystically just short of nameability. In dramatically unbreezeful contrast to Rosenberg’s piece is John Byrum’s “Transnon,” which consists, simply, of “TRA/ NS/ NON” in large white conventional letters against a black background. With the two cardinal directions missing in Rosenberg’s composition (north and south) in it, and black & white . . . and a backwards rendering of the word, “art,” this work seems almost monumentally engaged with ultimate dichotomies. Two more map/drawing/poems are presented by Richard Kostelanetz, from an early work of his using text-blocks of pertinent city impressions (e.g., “Boutiques,/ mostly in/ basements,/ their names/ as striking/ and transient/ as rockgroups:/ ‘Instant Pants’/ ‘Pomegranate’ . . .”) to represent various blocks of New York such as that defined by First and Second Avenues and St. Mark’s Place. Very local-feeling, intimate, accurate. A similar kind of opposition is at the heart of one of Nico Vassilakis’s contributions to this volume, “foremmett” (“emmett” being famous visual poet, Emmett Williams). It consists of a square with two parallel lines drawn horizontally across it near its middle; just above the upper line is “BL”; just below the lower line is “RED”; in between them is “UR.” In the corners of the upper section of the diagram the word, “blue,” is repeated; the word, “red,” is repeated in the corners of the lower section, while “purple” is printed once at each end of the narrow middle section. Another minimalist, almost overlookable piece that teems with the blur of science and sensuality, or where blue analysis becomes, or arises from, a red mood. . . . Three poems by Dick Higgins carry on this kind of letterplay in homage to Jean Dupuy, ina blom and wolf vostell. The first, just four lines in length, demonstrates the technique: “JEAN DUPUY/ NUDE JAY UP/ DUNE JAY UP/ PUN JAY DUE.” Then, following a charming mathematico-visual tribute to his daughter Amy, Karl Kempton does a lyrical take on the moon that includes a partial reflection of the moon as “wo u,” to magically suggest a fragment of “would,” or moon-distant wishfulness. Chuck Welch, active in mail art since 1978 as “the Crackerjack Kid,” contributes a moving swirl of words enacting Gaea’s flow which ends with “this dream truss/ clerestory/ Gaea’s blueprint,” but also a medallion-sort of visual poem that I liked less well: it looks nice but too boiler-platedly condemns white C(IA)olonialism and genocide, for my taste. A “cubistic” specimen of Gregory Vincent St. Thomasino’s Go series is here, too, with a more clearly visual poem from the same series that evokes a rescue at sea, a flare filling the sky with o’s while the excitement of the situation fills it with oh’s. St. Thomasino, and many of the other artists in the volume, provide readers with a short artist’s statement, by the way, which are quite useful. Others with first-rate pieces in this volume are M. B. Corbett, Harriet Bart, Harry Burrus, Spencer Selby, Stephen-Paul Martin, John M. Bennett (who does terrific things with near-empty frames of the tackily rubber-stamped kind well-known to those familiar with his work) and Paul Weidenhoff. All in all, Andryczuk’s anthology gives a valuable if rough idea of the terrain of current American vizlature. |

* * * * *

How I wish someone would tell me (in reasonable detail) why in the sixteen years since then, no one in the BigWorld has ever asked me for a piece like it?! Is it that inferior to the poetry-related pieces in magazines like the Atlantic? Or too different? Maybe too clearly politically-incorrect? Or is it that there is absolutely no one on the look-out for fresh talent? I have little to add to what I said in my column about Marilyn’s piece except that my first impression on seeing it again was that it seemed to me strongly Chinese (which I mean as a Large Compliment) and I again felt enlarged by its Q&A, this time by the ocean seeming to query the land . . . which provided, or was the answer. I was influenced a lot about some of Marton Koppany’s Q&A-related pieces that I’ve recently been enjoying and writing about.

Note: I corrected a typo or two in my column but left some of my now-obsolete terminology as is.

.

Entry 1405 — Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18

Thursday, March 27th, 2014

Off-the-top-of-my-head (although I’ve given the matter lots of thought on&off over the years), something I just wrote for the Shaksper Internet discussion group:

A problem I think interesting, and serious, is what should guide a reader of a poem to his reading of a poem (or any work of art). I claim there are four things he should consider: (1) the author’s intention; (2) how closely the poem may follow some fashion in poetry-composition of his time; (3) whether or not the poem is part of a sequence, and how, if that is the case, that affects the reading; and (4) what reading makes the poem best as a work of art for the given reader.

For me, a die-hard new critic, the author’s intention is irrelevant, except insomuch he explicitly reveals it in his work. If known, though, one should certain consult it to see if it helps one discover thing in the poem that one would have missed if not looking for them.

For me, it makes sense to investigate the compositional fashions of the time a poem was composed and use what one finds out about it that can be applied to one’s reading of the poem.

For me, a poem’s being explicitly, or even weakly implicitly, part of a sequence (as well as part of a poet’s ouevre) should also be taken in consideration. I as a poet, for instance, am almost obsessed with celebrating the coming of spring; so it would make sense for someone finding an ever-so-slight connotation of that in a poem I recently wrote about Columbus to accept it as in that poem (if he wants to).

For me as a reader of a poem, though, what is most important is what the poem’s text by itself can plausibly be said to say by itself that will maximize my aesthetic experience of it. If for instance, Milton tells me his poem justifies Jehovah’s treatment of the rebellious Lucifer (or whatever the devil is called in the poem [I haven’t read it for a while and have a lousy memory for names and the like] but I go along with Blake in finding Lucifer justified, and Jehovah a tyrant, I have no trouble ignoring Milton. I don’t find any explicit authorial intent behind Sonnet 18, so have no trouble taking the poem as what it on the surface is–a celebration of summer. (That’s a joke, but only here; in truth, I argue just that in the book I began but left hanging a while ago on Sonnet 18; I accept that the poem is doing other things, but consider them less important in the poem than summer.)

I vaguely know that nutty Platonic allegorical sequences were in vogue when Shakespeare wrote his sonnets, but don’t find inflicting allegor on sonnet 18, which is hard to do, for the most part, without straining worth doing–because, to my taste, the sonnet works much better as a lyrical poem taken for what it is on the surface. Similarly, church steeples work best for me not as glorifications of some god, or as avenues to Heaven–or as phallic symbols–but as celebrations of mountains or simple height and of Man’s ability to create.

I find Ian Steere’s reading of the first 126 sonnets as a sequence easy to go along with, I don’t find it a smooth sequence. It does near-certainly make the addressee male. But I don’t care. The plausibility of the sonnets as a sequence (or haphazardly organized collection) about the poet’s relationship (when it was worshipful) with a young XY-chromosome girl simply indicates authorial intention. But when what he wanted to say conflicts with what his poem just as plausibly can say (the celebration a a poet’s female opposite for her feminine physical beauty and feminine temperance, etc.), I grant the reader the right, again, to ignore authorial intent.

Conclusion: there’s nothing wrong with trying to determine how the poet wanted his poem read, nor with determining how fashion may have influenced it, nor with fitting it to a sequence with a view of finding the author’s intentions for the over-all sequence, or finding what one can plausibly interpret the sequence to best mean. But these ways of involvment with Sonnet 18, or any work of art should not keep one more interested in what it can do for him aesthetically from taking it only for the pleasure its words, by themselves, can give him.

.

Entry 1396 — Honesty as a Literary Commentator

Tuesday, March 18th, 2014

Full honesty as a literary commentator is impossible, if friendship is as important to you as it is to me (because I’m an Aquarian)–and are a competent critic. As a competent critic, you will have to find defects in even the best writer’s work. I wish we all were totally honest, though. I would very much like to learn the worst anyone can think of to say about my work. As I’ve always said, if I consider a criticism invalid, it will reassure me that others are not understanding my work sufficiently to give it the credit they should; if I consider it invalid (and I am capable of doing that, and have done it, or tried to do it, in the past) it should help me. It would also free me to be candid, or at least more candid, about my opinion of my critic’s work.

This is not to say I’m not reasonably honest, or actually ever dishonest. I almost never praise someone for doing anything he does not do. And my ratings of work are just about always absolutely sincere–that is, when I say my friend Richard Kostelanetz is the best big-picture critic of the literature of our time–make that, “the art” of our time, I mean it. (I feel I have said that but perhaps never so explicitly.) I mention Richard specifically here because he is one of the easiest writers to say negative things about because of his thick-skin. He has agreed with some of my negative comments about his art or ideas and disagreed with others–and that’s it. A few others of my friends are like that. Even them I avoid hitting with 100% candor.

I do believe that it may not matter since I suspect they are enough like me to recognize my lack of full candor–and bright enough to know pick up on my hints–when, for instance, I say something like, “X may be close to excessive sentimentality here,” instead of ascending into full candor by saying, “X idiotically descends into the most insipid sentimentality I’ve ever had the misfortune to come upon here.” And know when my praise goes over the top–as it does validly, I believe, when trying to make up for what I consider to b e the lack of appropriate recognition someone’s work is getting. That is, if X, whom I consider as good a poet as there is, is being much too ridiculously under-rated by the Establishment, I might say he’s twice as good a poet as any member of the Academy of American Poets, when I actually consider him only slightly better than such a poet. I do consider most of my friends in otherstream poetry to be doing better work than anyone in the Academy, but only because adding to the poets’ toolbox, perhaps not because truly superior. There is also my partial dishonesty in many of my sweeping negative judgements of poetry I confess I’m not familiar enough with to be as sure about as I sometimes sound.

Of course, I am sure I sometimes utter something false, maybe even obviously false, without know it. More often, but I hope not too often, I dishonestly ignore something pertinent that’s contrary to what I’m saying. Usually, again, that is to make up for the strength of the Establishment’s opposition. Or, I fear I must confess, to make friends who may help my career, or just to make friends. I think I’ve committed more dishonesties in order to avoid revealing my extreme political incorrectness. But that’s more a matter of avoiding areas I can’t be even half-candid in for areas that I can be, so really no more important than the fact that I avoid writing about higher mathematics because I know I can’t be even half-intelligent about it. Most of the time: I’m more than half-right in considering Cantor’s transfinite numbers scientifically meaningless because nothing more than a mathematical artifact like linguistic paradoxes like “This sentence is wholly false.”

I’ve seldom written my Unvarnished Opinion of anyone’s work. I may, if I live long enough, although I don’t think I have anything to say that will not be said by the time my generation has been gone long enough for near-total candor to be visited upon us. “Near-total” because I doubt that total condor is possible. For instance, how could anyone even a century from now say anything really mean about someone as nice as I am? If I said all I have to say about the art and artists–and commentators on the arts and got it published tomorrow, I probably wouldn’t get into too much trouble–because most of my friends in the fields involved would pretty much agree with my opinions where not on themselves or their favorites–and because they would nowhere reverse rather than somewhat negatively modify anything I’ve said before.

Oh, one last comment–there may be a handful of my colleagues whose work I’ve been completely honest about, because it really is as good as I say it is! And I’ve come close to complete honesty about those I consider Enemies of Poetry, albeit they have almost all been groups of unnamed individuals rather than individuals. I don’t believe I’ve ever lied when saying something like, “X is an excellent critic of the poets she treats but still qualifies as an enemy of poetry by not only ignoring a vast array of important contemporary poets but writing as though they don’t exist.”

Main conclusion: I think it is not difficult to determine what literary commentators of the past truly thought of contemporary writers, so striving for candor is not particularly important. I also think it won’t be long before all literature and commentary on literature will be done by computers, and the commentary will be completely candid.

There. Have I said anything worth saying? I only ask to get my word-count for this entry over a thousand. It is ridiculous how much that means to me, as if 1,000 is a praiseworthy achievement, 964 not.

.

Entry 1308 — Mine Review Continueth

Monday, December 23rd, 2013

I was going to celebrate the Winter Solstice with Zero Production, but then I found out yesterday, not today, was when it occurred, so I had to finish the review I was working on. I wrote over 1300 word, pretty good ones, I think. Below is one of the poems I dealt with, with my comments on it following it:

Something of what seems to me at the frontier of math-related poetry that I hope will be further explored in the future is Sarah Glaz’s fascinatingly strange “13 January 2009.” It consists of two texts side by side, one, “13,” with nothing in it but numbers (and equal signs), the other, “January 2009) devoted entirely to words about the dying of a man named Anuk whom I take to be an ancient Egyptian (in spite of the poem’s title!) I feel ready to go on for another thousand words at least about this poem, but will limit myself here to telling you that, according to its author, its “structure follows The Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic, which states that every positive integer greater than one may be expressed in a unique way as a product of powers of distinct prime numbers”—which (inexorable) process, I would add, is shown in “13.” I hope to say more in an essay on mathematical poetry I have in the works for this periodical. Conclusion: when I began thinking about this review, I had visions of making an insightful taxonomical study of its poems, but their “multi-dimensional links to mathematics and . . . wide range of styles” as Glaz has it in her introduction, and wide range of techniques, I’d add, made that too difficult a task. So all I have to say now is that I hope anyone still reading this has enjoyed my chatter as much as I’ve enjoyed indulging in it.

.

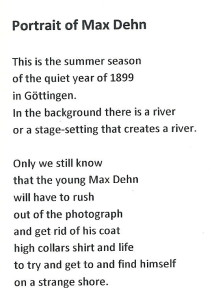

Entry 1307 — “Portrait of Max Dehn”

Sunday, December 22nd, 2013

Below is a poem from an anthology I’m writing a review of.

It’s by Francisco Jose Craveiro de Carvalho as translated from the Portuguese by Manual Portela. All it tells us (with a nice touch of surrealistic fantasy) is that Dehn was an emigrant–but it does so with the same kind of inspired empathy with which Keats famously described Ruth, amidst the alien corn. It’s here because I like it, but more because I wanted to say something about the Reviewer’s Delight I felt when, in writing about it, I saw my way to giving a poet what I feel is a high (and appropriate) compliment while also again praising my old favorite, Keats. Such delights are what make reviewing worth doing no matter how difficult it is at times.

.

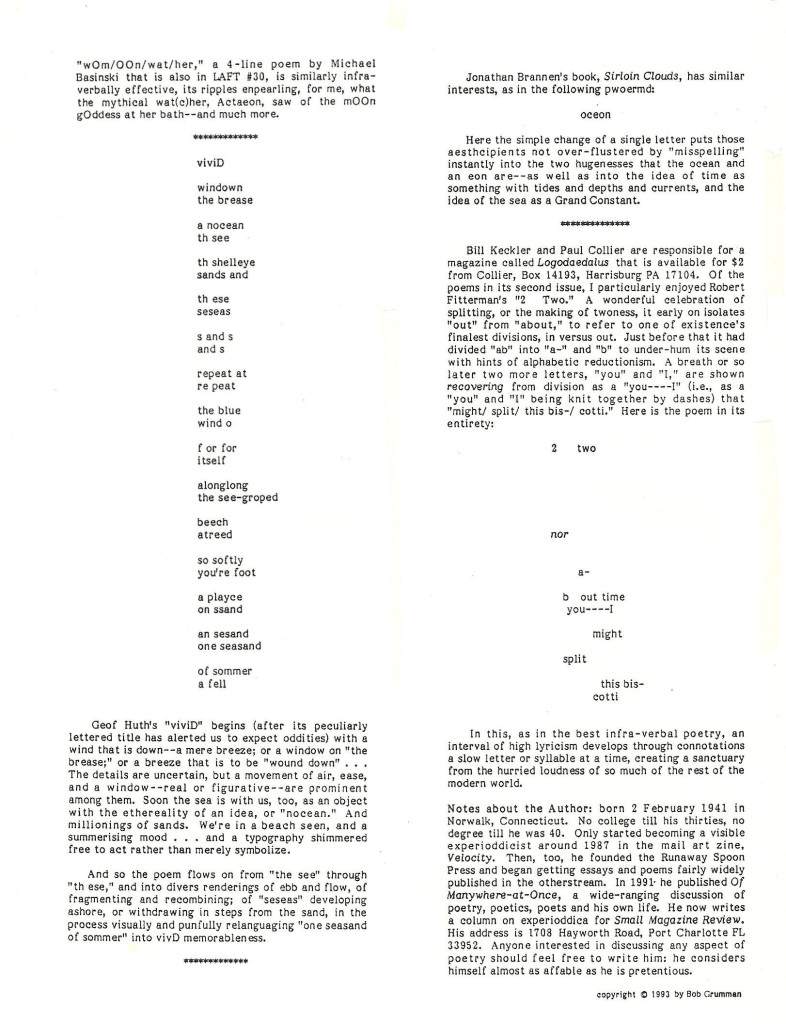

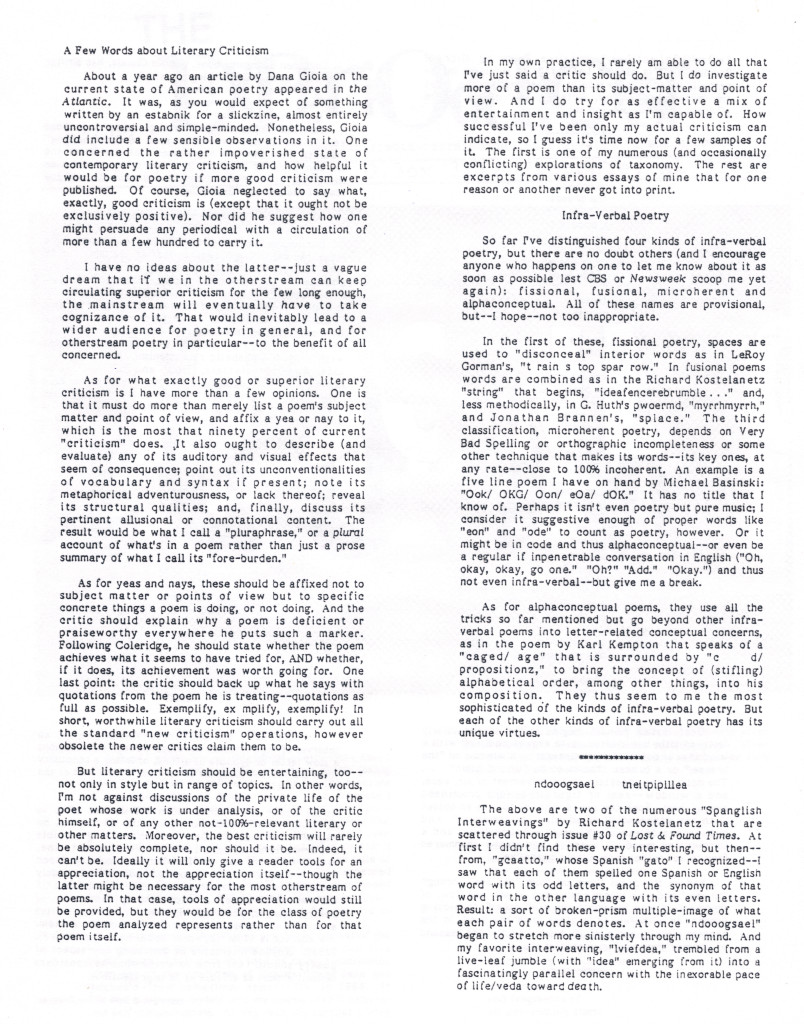

Entry 1207 — The Experioddicist, July 1993, P.4

Sunday, September 8th, 2013

Note: I consider Geof’s poem a masterpiece–one of more than a few he’s done I wish I’d done.

.

Entry 1206 — The Experioddicist, July 1993, P.3

Saturday, September 7th, 2013

Sorry–once again your imbecile of a blogmaster forgot to hit the button changing this from a withheld entry to a public one. Here it is two days late:

.

Entry 1162 — Ergodic Literature

Thursday, July 25th, 2013

Today I came across a new literary term I think as dopey as any of mine: “ergodic literature.” What follows what Wikipedia says about it, which I found especially intriguing because I know so much less about this kind of stuff than I’d like to.

Ergodic literature is a term coined by Espen J. Aarseth in his book Cybertext—Perspectives on Ergodic Literature, and is derived from the Greek words ergon, meaning “work”, and hodos, meaning “path”. Aarseth’s book contains the most commonly cited definition:

In ergodic literature, nontrivial effort is required to allow the reader to traverse the text. If ergodic literature is to make sense as a concept, there must also be nonergodic literature, where the effort to traverse the text is trivial, with no extranoematic responsibilities placed on the reader except (for example) eye movement and the periodic or arbitrary turning of pages.

Cybertext is a subcategory of ergodic literature that Aarseth defines as “texts that involve calculation in their production of scriptons” (Cybertext, page 75). The process of reading printed matter, in contrast, involves “trivial” extranoematic effort, that is, merely moving one’s eyes along lines of text and turning pages. Thus, hypertext fiction of the simple node and link variety is ergodic literature but not cybertext. A non-trivial effort is required for the reader to traverse the text, as the reader must constantly select which link to follow, but a link, when clicked, will always lead to the same node. A chat bot such as ELIZA is a cybertext because when the reader types in a sentence, the text-machine actually performs calculations on the fly that generate a textual response. The I Ching is likewise cited as an example of cybertext because it contains the rules for its own reading. The reader carries out the calculation but the rules are clearly embedded in the text itself.

It has been argued that these distinctions are not entirely clear and scholars still debate the fine points of the definitions. ]

One of the major innovations of the concept of ergodic literature is that it is not medium-specific. New media researchers have tended to focus on the medium of the text, stressing that it is for instance paper-based or electronic. Aarseth broke with this basic assumption that the medium was the most important distinction, and argued that the mechanics of texts need not be medium-specific. Ergodic literature is not defined by medium, but by the way in which the text functions. Thus, both paper-based and electronic texts can be ergodic: “The ergodic work of art is one that in a material sense includes the rules for its own use, a work that has certain requirements built in that automatically distinguishes between successful and unsuccessful users” (Cybertext, p 179).

The examples Aarseth gives include a diverse group of texts: wall inscriptions of the temples in ancient Egypt that are connected two-dimensionally (on one wall) or three dimensionally (from wall to wall or room to room); the I Ching; Apollinaire’s Calligrammes in which the words of the poem “are spread out in several directions to form a picture on the page, with no clear sequence in which to be read”; Marc Saporta’s Composition No. 1, Roman, a novel with shuffleable pages; Raymond Queneau’s One Hundred Thousand Billion Poems; B. S. Johnson’s The Unfortunates; Milorad Pavic’s Landscape Painted with Tea; Joseph Weizenbaum’s ELIZA; Ayn Rand’s play Night of January 16th, in which members of the audience form a jury and choose one of two endings; William Chamberlain and Thomas Etter’s Racter; Michael Joyce’s Afternoon: a story; Roy Trubshaw and Richard Bartle’s Multi-User Dungeon (aka MUD1); and James Aspnes’s TinyMUD.

All these examples require non-trivial effort from the reader, who must participate actively in the construction of the text.

The concepts of cybertext and ergodic literature were of seminal importance to new media studies, in particular literary approaches to digital texts and to game studies.

Note: I found the term, “scripton,” interesting, so googled it until I was give this: “Aarseth suggests the terms scripton and texton to describe the ontological dualism of a cybertext: Scriptons are ‘strings (of signs) as they appear to readers’ and those parts of a cybertext that are not directly accessible to the reader/user are termed textons and defined as ‘strings (of signs) as they exist in the text’ (Aarseth, 62). In conventional literature, the scriptons equal the textons because the immobility of the signifiers ensure that there can be no divergence between the text that is stored on the page and the text that is displayed on it.” I use the term, “texteme,” to indicate the smallest unit of text in print. Quite a bit different.

.

Entry 803 — Insulting BigName Critics

Wednesday, July 18th, 2012

After Finnegan, sitemaster of New-Poetry, let New-Poetry members know that we could find essays by various critics commenting on the current state of American Poetry at the VQR Symposium yesterday, I visited the site, read some, skimmed some, then posted the following at New-Poetry:

Thanks much for this, Finnegan. All these critics and Perloff (whom I count as part of the VQR Symposium group although she withdrew from it because she has remained an important part of it, anyway) is the only one who mentions visual and performance poetry, and all she does is mention them. The most visible two poetries of the Otherstream. But that’s enough to keep me from judging her thoughts on the contem-porary poetry scene the worst in this collection. The others are too closely worthless to pick out one for worst effort.

I will admit one thing not too hard to admit: a few of these estabniks seem somewhat familiar with what they deem a new sort of poetry—conceptual poetry—a kind of poetry, if it’s poetry (and Perloff questions whether at least some texts called conceptual poetry are poems) with which I was unfamiliar. But I’ve always said in my lists of new and newish poetry that I was sure I’d missed some, and know I’ve fallen behind badly in keeping up with various kinds of cyber poetry, never felt comfortable with my take on sound poetry, and only now believe I’m coming to terms with language poetry (although I arrogantly also feel I’ve known more about it for twenty years than just about anybody writing it, or writing poetry called language poetry, including especially Ron Silliman).

From the few examples of conceptual poetry I’ve seen, I have what I think is Perloff’s view, that it’s too similar to dada to be new, and—as I said—possibly prose (of a kind I’ve named “conceprature” to go with similar taxonomical terms I’ve used for “poetry” that’s really prose, “evocature” for prose poems, and “advocature” for lineated propaganda texts. I also use “informrature” for lineated texts like names and addresses on envelopes that are clearly not poems). Having said all that, I do believe that conceptual poets-or-prosists (note: “prosists” is an ad hoc term; I want something better, preferably already in use) are cutting edge even though working in a variety of literature that’s been around a long time—because (1) they are still finding significantly new things to do in it (new to me, anyway) the same way I believe a few visual poets are still finding significantly new things to do in visual poetry, which—in its modern phase—has now been around a century, give or take a decade or two, its start being still controversial; and (2) only a very few visible critics know about them, and only one, Perloff, has so far written meaningfully about them.

I should be kinder to Perloff than I have been for the past 25 years, and will be from now on, I’m pretty sure. But nothing is harder for someone fighting against the status quo not to blow up at than another fighting against it differently (usually much less differently than its seems to both at the time).

Below is perhaps the best example of anti-Otherstream gatekeeping in the tripe Finnegan linked to, a passage from Willard Spiegelman’s hilariously-titled essay, “Has Poetry Changed? The View From the Editor’s Desk.” Its title is funny because it contains not one word about how American poetry has changed over the past 30 years or so. (Note, by the way, another change in my boilerplate: “30,” not “50” years as I so long contended. I finally realized that Ashbery and his followers were, when breaking into prominence, using techniques not in wide use at the time–although far from revolutionary.)

“Some years ago Helen Vendler said she was giving up reviewing or generally writing about new books of poetry by younger poets. She had not lost her acumen, her interest or her powers of perception; rather, she said that she lacked the right cultural frame of reference to be an appropriate audience, let alone a judge. She knew about gardens and nightingales, Grecian urns and Christian theology, but not about hip-hop or comic books, and these provide the material, or at least the glue, for many of today’s poems. Poetic subjects, voices, diction, and tone change. And forms, like subjects, change as well. She wanted to leave the critical field open to younger people like her colleague Stephen Burt, a polymath who knows the ancients and the moderns, the classics and the contemporary. He listens to indie bands and reads graphic novels. He flourishes amid the hipsters as well as the sonneteers.” Etc.

Why is this especially stupid, in my view? The idea that the main thing a critic needs to be familiar with to write about poetry is subject matter. Oh, and “voices, diction and tone.” Oops, “forms,” too. No mention of what Vendler has been drastically ignorant of since she was first writing about Ashbery: technique. Perhaps I’m wrong to consider it the most important component of poetry, but it most certainly is as important as “voices, diction and tone.”

Then there is her leaving the field open to people like Stephen Burt. A Harvard professor! And no more knowledgeable than Vendler about what’s going on in poetry now. Here’s one thing Wikipoo calls him recognized as a critic for, his definition of what I call jump-cut poetry (but long ago referred to it a few times as “elliptical”): “Elliptical poets try to manifest a person—who speaks the poem and reflects the poet—while using all the verbal gizmos developed over the last few decades to undermine the coherence of speaking selves.” I like his “all the verbal gizmos.” Does he mention even some of those invented way before his time by Cummings. I don’t know his criticism well enough to be sure the answer is no, but I’d be willing to bet ten bucks it is.

I’d be interested to know why what I’ve written here contributes less to the discussion in VQR of the current state of American Poetry than the essays in it. Anyone interested in telling me? Or even in telling me why I’m not worth telling? I’ve issued challenges like this before. No one’s yet answered one. At least one that doesn’t significantly misrepresent me, and escalate into ad hominem arguments and plain insults.

Note: I’m pretty sure that 15 or 20 years ago, one of the two times I was stupid enough to apply for a Guggenheim grant, Willard Spiegelman got one in the field I’d applied for one in. I can’t remember how he described his winning project except that it was lame, even for a mainstreamer. (Richard Kostelanetz, a former winner of a Guggenheim, had recommended me to the Guggenheimers, who then invited me to submit an application, so it wasn’t all my fault.)

.