How the Brain Processes Visual Poetry

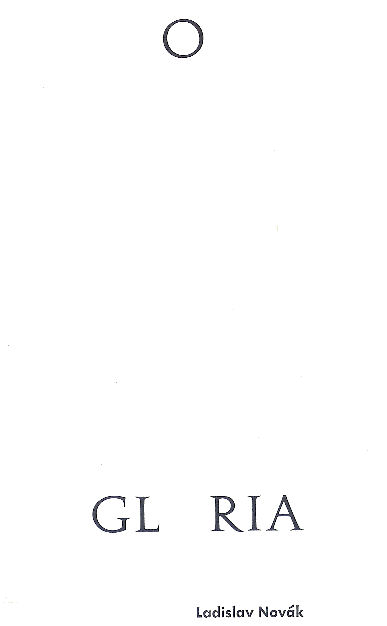

14 December 2005: Now to begin my first attempt to use my knowlecular theory of psychology to show how appreciation of a visiophor (visual metaphor) takes place, working with “Gloria.”

When the engagent first sees this poem (assuming he has little or no background in visual poetry), he is bothered (at least momentarily) by its “misspelling.” What happens in terms of my theory is that (1) his knowlecule (cerebral molecules of knowledge) for g followed by his

knowlecule for l “predict” or expect (actually send energy to) various other knowlecules (mostly those representing vowels, including the one for o) but not to the knowlecule for a blank. His expectation is frustrated, so he will experience a trace of pain. He will interpret

the poem (probably subconsciously) as a puzzle.

(2) Once the engagent has experienced the knowlecules for r, i and a–and o, when he sees the out-of-place o–he will partially solve the puzzle by determining what word the letters spell. But he will still experience pain because of the word’s “misspelling.” The high-flung o will continue to be “wrong,” unpredicted, unfamiliar, and–in my theory–unfamiliarity is the sole cause of cerebral pain.

(3) The engagent’s pain will cause him to lower his cerebral energy. This, in turn, will let possible solutions to the puzzle in the form of images and ideas swarm through his mind (subconsciously). Most of the images and ideas will be of no help, but–with luck–one of them will be the knowlecule for [cathedral-shape] due to the shape of the word, “gloria,” as a graphic image with its o suggesting the top of a steeple, coupled with the knowlecule for [religious grandeur], almost certain to be activated by the conventional connotation of the word, “gloria.”

(4) If this connection does begin to take place, it will cause pleasure–because the knowlecule for [cathedral-shape], helped by the religious grandeur context, will link to the knowlecule for the poem as a whole “logically.” That is, the engagent’s brain will “predict” the [cathedral shape]’s linking back to the poem. The engagent’s pleasure will increase the engagent’s cerebral energy. This will make his “solving” the puzzle of its “misspelling” quickly enough, if things go well, to appreciate it.

I am aware that my analysis is very rough. It is incomplete, too. I left out important points about “accommodance” and “accelerance,” for instance. I felt like I was responding to, and barely passing, an essay exam. So, I will return to it tomorrow, and for several days thereafter, I expect.

15 December 2005: To continue with my analysis of the nature of metaphor appreciation, I need to introduce and define five terms connected to my theory of psychology. They all have to do with general intelligence. Character, accommodance, accelerance and cerebrachive.

Character is the mechanism that determines one’s basal level of cerebral energy–which in turn determines how strongly one can bring up memories, and hold on to them.

Accommodance is the mechanism that determines how quickly and how low one can lower one’s level of cerebral energy, and keep it lowered–which in turn determines how strongly one can let in data from the external environment without interference from memories.

Accelerance is the mechanism that determines how quickly and how high one can raise one’s level of cerebral energy, and keep it raised–which in turn determines how fast one can find answers (but not how correct those answers may be).

These three mechanisms are the basis of general intelligence, in my psychology. The cerebrachive (“cerebral archive”) is simply one’s store of information, or knowlecules–or unified representations of data ranging from, say, a letter, to, say, a philosophy (but capable of being much smaller than the former, and much larger than the latter).

Oh, and here is a redefinition of a common term in psychology, “the subconscious.” For me, it is that part of the cerebrachive which is readily available to consciousness, the latter simply being all that we are aware of at a given moment–or what I believe just about everyone

would take it to be.

Tomorrow, I plan to show how the three mechanisms of general intelligence interact with one another, and with the cerebrachive, to experience a metaphor.

16 December 2005: To continue, let me list my terms again:

Character is the mechanism that determines one’s basal level of cerebral energy–which in turn determines how strongly one can bring up memories, and hold on to them.

Accommodance is the mechanism that determines how quickly and how low one can lower one’s level of cerebral energy, and keep it lowered–which in turn determines how strongly one can let in data from the external environment without interference from memories.

Accelerance is the mechanism that determines how quickly and how high one can raise one’s level of cerebral energy, and keep it raised–which in turn determines how fast one can find answers (but not how correct those answers may be).

The Cerebrachive (“cerebral archive”) is simply one’s store of information, or knowlecules– or unified representations of data ranging from, say, a letter, to, say, a philosophy (but capable of being much smaller than the former, and much larger than the latter).

The Subconscious is that part of the cerebrachive which is readily available to consciousness, the latter simply being all that we are aware of at a given moment–or what I believe just about everyone would take it to be.

To significantly appreciate a metaphor, all three of one’s mechanisms of general intelligence must be superior. First of all, one’s character must keep one’s cerebral energy at a generally high level. This will cause one to be significantly bothered by the unconventionality of “Gloria” when he first encounters it. Or: he will very energetically maintain his expectation as to what the work should look like, so its failure to match his expectation will pain him much more than it might someone with medium or low character. Consequently, if he succeeds in appreciating it, it will increase the relief (according to my theory) he will experience (pleasurably) when he does so. More on this in due course.

Secondly, his accommodance must be effective at quickly responding to his pain and lowering the level of his cerebral energy. This will unfocus him, allow random memories more readily to break into his unconscious, make him more susceptible to extraneous stimuli in the external environment–in short, increase his chances of quickly connecting to a solution to the puzzle the work involved has become for him.

His having a large cerebrachive will be important, too–the larger, the better, for the most part. His accommodance is important here, too, for what it has done (crucially) in the past to increase the size of the engagent’s cerebrachive, and the variety of the items in it.

The engagent’s accelerance must also be of high quality, and thus able to react as soon as something in his subconscious indicates it may “solve” the poem by swiftly increasing the engagent’s level of cerebral energy to a maximum. It will tend to respond more violently the more frustrated the poem has made the engagent–to get back to the significance of how attached to his expectation of the conventional presentation of the poem that its actual presentation rebels away from. I claim that the more a person is frustrated, the more strongly activated (in turn) both his accommodance and accelerance will be.

Up to a point. If it takes too long for a solution to pop up, the mechanism responsible to activating the accommodance and accelerance will become too exhausted to strongly do that–if it even can, finally, do it. Hence, the need for both those mechanisms to be able to act quickly and decisively.

Summary to this point: one needs to be intelligent to appreciate metaphors. One needs, in fact, to have superior specimens of all three of general intelligence’s mechanisms to be able to appreciate them.

17 December 2005: Now for an attempt to show my mechanisms (definitions at the end of this entry) carrying out an appreciation of “Gloria.”

The engagent begins to read the poem with high character. A copy (I’m speaking more or less figuratively) of what he expects to read forms in his memory, but what he sees fails to match it. The o is displaced. Result: discordance. Pain. The latter is felt in the evaluceptual center.

As a result, it starts building up cerebral energy for use in combatting the source of the pain. Some of the energy goes toward activating the engagent’s accommodor, which is the name I’ve just made up for the mechanism that runs the operation of accommodance. The acceletor

would be the mechanism taking care of accelerance.

For reasons I won’t get into here, accommodance causes random memories to seep into the subconscious. Because it lowers the cerebrum’s ability to activate memories in general, random images from the external environment–as well as unrandom percepts (data bits of perceptual origin) will enter the subconscious, as well. Momentary couplings of various knowlecules in the subconscious will jar other random knowlecules to be remembered (i.e., to enter from the cerebrachive). Soon, bits and pieces of extraneous data will fill the subconscious.

By accident, at some point, something like the following will occur: part of the engagent’s knowlecule of the shape of the word, “gloria,” on the page will encounter a piece of a memory of a church. The engagent will (subconsciously) recognize that the shape is appropriate for a church, or experience the shape plus the church as something familiar. The Evaluaceptual Center will sense the pleasure this causes and set the acceletor into action. The increased energy resulting will speed the “solution”–that is, it will cause the full connection between word-shape and church-shape to be quickly made. The engagent will appreciate the metaphor.

Character is the mechanism that determines one’s basal level of cerebral energy–which in turn determines how strongly one can bring up memories, and hold on to them.

Accommodance is the mechanism that determines how quickly and how low one can lower one’s level of cerebral energy, and keep it lowered–which in turn determines how strongly one can let in data from the external environment without interference from memories.

Accelerance is the mechanism that determines how quickly and how high one can raise one’s level of cerebral energy, and keep it raised–which in turn determines how fast one can find answers (but not how correct those answers may be).

The Cerebrachive (“cerebral archive”) is simply one’s store of information, or knowlecules– or unified representations of data ranging from, say, a letter, to, say, a philosophy (but capable of being much smaller than the former, and much larger than the latter).

The Subconscious is that part of the cerebrachive which is readily available to consciousness, the latter simply being all that we are aware of at a given moment–or what I believe just about everyone would take it to be.

18 December 2005: One complication with what I’ve said so far about how one appreciates a metaphor, according to my (knowlecular) theory of psychology, is that I’ve assumed only intelligence involved is general intelligence (which–since yesterday–I call “cerebrigence,” to

distinguish it from the other intelligences I will be discussing). I’m partly in the Howard Gardner school of multiple intelligences. I differ from him as to what specific intelligences we have, and as to the importance of cerebrigence. (For a long time he considered it–under the name, g-factor–non-existent; of late he grants it minor importance*.) I consider cerebrigence more important than any sub-intelligence.

But the sub-intelligences are highly important, and often the difference between high effectiveness in a vocation and mediocrity. Verbal intelligence is such a vital sub- intelligence where appreciation of metaphor is concerned. It uses the same mechanisms– character,

accelerance, etc.–as cerebrigence, but does so locally, in what I call the verbiceptual awareness, a subdivision of the reducticeptual awareness. The latter is where we deal with concepts, abstractions, symbols. I hypothesize that the verbiceptual awareness is where we process language. It breaks down further into the dictaceptual center, which handles human speech, and the texticeptual center, which handles the written word (and is evolutionarily very new). It gets hairier, but I’ll leave discussion of other related verbiceptual details, such as the function of the Broca’s Area, for another time.

My theory, needless to say, is based principally on guesswork. The latter ranges from grade-A guesswork, or guesswork I believe strong supported by empiracal evidence such as the existence of the verbiceptual awareness in some form, down to grade-P guesswork, such as my belief that housecats are more cerebrigent than women. A grade-B guess of mine is that subawarenesses such as the verbiceptual have augmenters that increase the effect of the cerebrigentical devices I’ve introduced (such as decelerance) when those devices operate within them. It follows that people vary in the effectiveness of their subawareness augmenters (and that such augmenters vary in effectiveness from one of a person’s subawarenesses to another). I believe, too, that some people’s peripheral nervous system’s are better at picking up subtle nuances of speech than others, or at reading fine print, and so forth. So they have better data to work with. Some people, then, will be better at appreciating metaphors than others because of their being . . . better with words.

There’s yet more to genuine verbal effectiveness: the part that depends on certain of the brain’s many association areas. There are three of major importance: the visio-verbal association area where words connect to visual memories; the verbo-auditory association area where words connect to averbal auditory memories (i.e., sounds of nature rather than sounds of words) and the visio-verbo-auditory area (a grade-C guess, I should insert) where words connect to memories that combine sound and sight. Obviously, the better these areas operate, the more easily a person will make the kind of extra-verbal connections he needs to in order to appreciate the best metaphors near-maximally. The auditory and visual awarenesses must also function well for this to happen, since these association areas feed off them.

So, today’s lesson has been that one must have not a only an effective cerebrigence, but an effective verbal area (verbiceptual awareness) and effective related association areas, to be able to appreciate metaphors reasonably well. I realize that common sense should have told you that, but am interested in setting out what I consider the psychological details of the matter.

* I like to think that I helped change his mind, for I refuted his view with some pretty good arguments in a letter to him that he never answered some years ago, but he probably never read the letter; his secretary got back to me, though, telling me he would be glad to read

any published material of mine on the subject, the standard way estabniks brush off their superiors–and, yes, inferiors. I sent him a copy of the piece I wrote on creativity that I later posted here at my blog.

19 December 2005: It would seem I’ve made an error in presentation: I’ve been using a specialized metaphor–a visiophor–to show how one processes conventional metaphors–i.e., solely verbal ones. The process goes a little differently with the latter, so I’d better backtrack– to a simple metaphormation (as I call a metaphor and its referent, or the thing in the foreground and the thing it stands for together): Paradise Lost is a cathedral.

The process is not too much different from that described. One perceives “Paradise Lost is” with high character which focuses the mind to “expect” something like “a great poem” or “boring” or the like. In fact, according to my theory, the engagent’s brain contacts memories such as the verbal knowlecule, “a great poem,” and begins to remember them. But “cathedral” occurs. A falsehood, literally speaking. Disruption. The evaluceptual center reacts by calling accommodance into play. The knowlecule, {Paradise Lost}, will weakly continue to transmit cerebral energy (or, more accurately, molecular packets that can be converted to energy) to appropriate memories, many of them connotations (of various degrees of aptness) which would not be activated if the engagent’s character had remained high (because of too much focus, or cerebral narrowness). At the same time, accommodance will cause the knowlecule, {cathedral}, to assist a wide variety of partial memories into the subconscious, many of them also connotations (of various degrees of aptness) having to do with cathedrals.

Certain of these latter memories should quickly stick to certain of the connotations of Paradise Lost–“grandeur,” for instance; “solemnity”; “architectural impressiveness”; “result of faith”. . . . Accelerance taking over, something like “Paradise Lost is a cathedral in architectural grandeur” will result: the “solution” to the puzzle of how a poem can be called a building.

The differences in the process just described and the process yielding the appreciation of “Gloria” are due to the one major difference in the metaphors: “cathedral” as a metaphor for a poem is verbally stated in the example above; in the previous example, it is visually depicted (as a rough cathedral-shape made of typography). Ergo, whereas one has to have an effective verboceptual awareness to be able readily to appreciate metaphors such as “cathedral” is for Paradise Lost, one needs much more to be able to appreciate the kind of metaphor the distribution of the letters of “gloria” make up: besides an effective verboceptual awareness, one needs an effective visioceptual awareness to be able quickly to see the print on the page, and and effective visio-verbal association area to allow the work’s visual datum to interact with the work’s verbal datum.

So, in my clumsy way, I’ve answered both how the appreciation of a conventional metaphor takes place, and suggested the talents the appreciator must have, and how the the appreciation of a visual metaphor takes place, and suggested the talents the appreciator in that case must have. Which gets me back to Geof Huth’s original interest in where a visual poet comes from. Clearly, he must be, first of all, such an appreciator of visio-verbal metaphors–or born with superior verbal and visual intelligence, and high cerebrigence. It goes without saying that he needs more to become a visual, poet. I tend to believe that the more that he needs is simply better verbal, visual, and general intelligence than lesser appreciators of visio-verbal metaphors. In my view, talent automatically generates use of talent. Once a person can near-maximally enjoy visio-verbal metaphors, he will need to make his own.

20 December 2005: Note: the way a person appreciates a metaphor is very similar to the way a person appreciates a joke. (1) He is bothered by the equivalent of a misspelling; (2) his accommodance, awakened, exposes him to potential “solutions,” or connections that make the apparent error seem logical; (3) one such solution is potent enough to turn his accelerance on and, with its help, become fully active. It is at this point that appreciation of metaphor diverges from appreciation of joke. It With a joke, step (3) ends the experience with laughter. With a good poetic metaphor, step (3) causes step (4), during which the engagent goes on to make other fruitful linkages, such as that of the o to the moon, or a ballon–or something airbourne, light, ascendant; and to the word, “oh,” in the case of the metaphor “gloria” features.

Also, there won’t be the hostility in the engagent’s encounter with the metaphor that there almost always will be in an encounter with a joke. But one will usually smile, even laugh, with a good metaphor.

With that, I end this rough attempt to apply my knowlecular theory of psychology to metaphor- and vispo-reception. I hope eventually to deliver a smoother discussion of the matter.