Archive for the ‘Eugen Gomringer’ Category

Entry 1553 — Back to “Silencio.”

Friday, August 29th, 2014

Entry 740 — The Special Value of Solitextual Visual Poems

Wednesday, May 16th, 2012

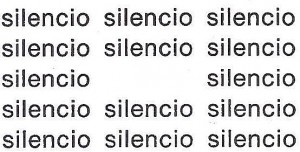

In my taxonomy a solitextual visual poem is a poem consisting solely of textual elements that are significantly visioaesthetic–that is, what their text is visually is necessary to the poem’s central aesthetic effect. A famous example is this, by Eugen Gomringer:

I’m posting it again to illustrate two points. One is that is has always been considered a “concrete poem,” because it consists of nothing but words, yet has a visual component absolutely necessary for it to have any appreciable aesthetic value–the visual appearance of the absence of text in one part of it. That, of course, is what makes the poem a classic by depicting a silence greater than the silence of printed words–by, that is, surprising one encountering the poem (with the ability to appreciate it) with a sudden poetic understanding of something central to existence.

My other point occurred to me when recently reading something by Richard Kostelanetz in which he speaks of finding “that with words alone (he) can make the most powerful images available to (him).” In context, he seems to be suggesting that these images are more powerful than those others get with works combining verbal and graphic elements. I can’t go along with that. However, on reflection, I saw how solitextual visual poems like Gomringer’s and Kostelanetz’s can be said to have a unique aesthetic punch compared to poems mixing graphics with text. That’s because of the increase in the unexpectedness of whatever it is a solitextual visual poem does visioaesthetically compared to what the other kind of visual poem does. I claim that both kinds of poems will, if successful, put an engagent in Manywhere-at-Once, or a part of the brain neither a conventional poem or conventional visimage (graphic image) is likely to put one, but the engagent will already be partway into that location upon first encountering a poem combining the visual and the verbal whereas he will only be in the verbal part of his brain until the pay-off in a purely solitextual poem, so the pay-off will come more forcefully, and probably be more intense. The mixture of graphics and text, however, will be able to make up for the reduced intensification by increased richness–by going to a larger Manywhere-at-Once or inter-connected Manywhere-at-Onces. Equal but different.

Entry 48 — Full Effectiveness in Poetry

Saturday, December 19th, 2009

I’m skipping ahead to old blog entry #796 today to make a point about my recent cryptographiku. #796 has Cor van den Heuvel’s poem:

. tundra

I go on in the entry to say I believe Eugen Gomringer’s “Silencio,” of 1954, was the first poem to make consequential visiophorically expressive use of blank space:

. silencio silencio silencio . silencio silencio silencio . silencio silencio . silencio silencio silencio . silencio silencio silencio

I finish my brief commentary but then opining that van den Heuvel’s poem was the first to make an entire page expressive, the first to make full-scale negative space its most important element. Rather than surround a meaningful parcel of negative space like Gomringer’s masterpiece, it is surrounded by meaningful negative space. I’m certainly not saying it thus surpasses Gomringer’s poem; what it does is equal it in a new way.

I consider it historically important also for being, so far as I know, the first single word to succeed entirely by itself in being a poem of the first level.

Then there’s my poem from 1966:

. at his desk

. the boy,

. writing his way into b wjwje tfdsfu xpsme

This claim to be the first poem in the world to use coding to significant metaphorical effect. Anyone who has followed what I’ve said about “The Four Seasons” should have no trouble deciphering this. I consider it successful as a poem because I believe anyone reasonably skillful at cyrptographical games will be able (at some point if not on a first reading) to emotionally (and sensually) understand/appreciate the main things it’s doing and saying during one reading of it–i.e., read it normally to the coded part, then translate that while at the same time being aware of it as coded material and understanding and appreciating the metaphor its being coded allows.

I’ve decided “The Four Seasons” can’t work like that. It is a clever gadget but not an effective poem because I can’t see anyone being able to make a flowing reading through it and emotionally (and sensually) understanding/appreciating everything that’s going on in it and what all its meanings add up to, even after study and several readings. Being able to understand it the way I do in my explanation of it not enough. This is a lesson from the traditional haiku, which must be felt as experience, known reducticeptually (intellectually), too, but only unconsciously–at the time of reading it as a poem rather than as an object of critical scrutiny, which is just as valid a way to read it but different.