Charles Alexander

Poet, Book Artist, Critic, Publisher

Alexander was born in Honolulu, grew up mostly in Norman, Oklahoma, was educated at Stanford University and the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and has lived in Tucson for most of the last 14 years, including at present, with his wife Cynthia Miller, one of the premier visual artists of the American Southwest. His e.mail address is [email protected].

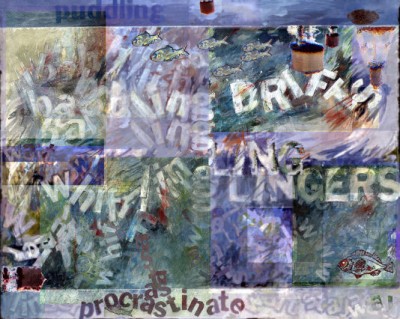

Charles Alexander’s books of poetry include Hopeful Buildings (Chax Press, Tucson, 1990) and arc of light / dark matter (Segue Books, New York, 1992).

Two chapbooks are forthcoming in winter 1998: Four Ninety Eight to Seven from Meow Press (Buffalo, New York) and Pushing Water from Standing Stones Press (Morris, Minnesota).

Alexander has also published reviews and critical essays on contemporary literature and culture. He is the founder and director of Chax Press, which was begun in Tucson, Arizona in 1984; Chax moved to Minneapolis from 1993 through 1996, and returned to Tucson in the summer of 1996. Chax is a publisher of handmade letterpress books and trade literary editions, both of which explore innovative writing and its conjunction with book forms. Through Chax Press, from 1986 to the present Alexander has organized literary readings, talks, workshops and presentations by artists. From 1993 through 1995 Alexander was executive director of Minnesota Center for Book Arts, the nation’s most comprehensive center for the arts of the book, both in terms of programs and artists’ studio facilities. As its director, Alexander completed the production of the visual/literary artists’ book, Winter Book in 1995 with visual artist Tom Rose.

In addition he has directed educational programs and a variety of

artists’ residencies, creative productions, and other works. He was the

organizer and director of the 1994 symposium, Art and Language: Re-Reading the Boundless Book, one of the foundational symposiums in the recent history of the book arts. From this symposium, he edited the formative collection of essays, Talking The Boundless Book: Art, Language, and the Book Arts (Minnesota Center for Book Arts, Minneapolis, 1996).

Alexander has given poetry readings, lectures, and workshops throughout the country at colleges, universities, art centers, and other locations, including at the University of Alabama, the University of Arizona, theState University of New York at Buffalo, Painted Bride Arts Center in Philadelphia, Small Press Traffic in San Francisco, Canessa Gallery in San Francisco, the University of Washington, Pacific Lutheran University in Tacoma, Scottsdale Center for the Arts, and many more. Alexander has also performed poetry in galleries and art centers, has collaborated with musicians and dancers, and in general brings to poetry a broad sense of artistic and collaborative possibility.

Poet Robert Creeley writes that Alexander’s work “hears a complex literacy of literalizing words. By means of a fencing of statements, sense is found rather than determined. The real is as thought.” And, concerning his 1992book, arc of light/dark matter, the poet and critic Ron Silliman writes, “Now Charles Alexander pushes the envelope of what is possible in writing

ven further, to the ends of the universe. And beyond. . . This is the most

sensuous, intelligent, rewarding writing I’ve read in ages.”

Christopher W. Alexander

Poet/Critic/Publisher

Alexander’s regular address is PO Box 522402, Salt Lake City, UT 84102; e.mail will reach him at [email protected].

Born 25 March 1970, in Akron, OH, he is espoused (unofficially) to Linda V. Russo and is the father of one child.

He works as a computer tech teacher. He has a B.A. from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and a master’s from Boston University. Besides composing poetry, he writes cultural criticism and acts as a press collective co-ordinatoror editor. He likes both classical and hardcore music (composers: Bach, Beethoven, Schoenberg, Shostakovich, Ives, Cage; bands/musicians: The Minutemen, Sonny Rollins, Charles Mingus), film (Derek Jarman’s TheGarden; The Last of England), politics (Intifada, IRA, American domestic; foreign affairs), hiking, bicycling, painting; sculpture (Picasso, Diego Rivera, F. Kahlo, Duchamp).

Among the books closest to him are The Brothers Karamazov and Berger’s A Painter of OurTime; he is also high on the play, Woyzeck. He describes his religious outlook as buddhist/none, marxist. He enjoys following pro basketball, but only Chicago games & only occasionally. He practiced Tae Kwon Do for 10 yrs., now lifts weights, jogs, goes on extended hikes, bicycles, cross-country skis, and occasionally goes snowshoeing.

About his background in science and philosophy he says, spent 2 yrs. of my undergrad studying genetics, got bored; moved over to american lit. “I do read a good deal of philosophy,” he says, “particularly Nietzsche, Hegel, Marx, Wittgenstein, Derrida, the polit. philosophy of the Frankfurt School critics (esp. Adorno), Foucault, M. Bakhtin; V. Volosinov, Pierre Bourdieu, Raymond Williams, etc.— focus on political & language phi.

About his life-in-general, Alexander says, “complicated, but good overall. L.& I are relatively poor, but happy together, nominative press collective is taking off a bit, my poetic work is good if difficult.”

He had work in n/formation 1: spring 1997 and is currently viewable on the web at http://choengmon.lib.utah.edu/~calexand/nonce. His book, Dusky Winders (nominative press collective, 1996) has been reviewed in Taproot Reviews. The contemporary poets important to him are Robert Creeley, Donald Revell, Charles Bernstein, Barrett Watten, Tina Darraugh, Peter Inman, Ron Silliman, Alan Halsey, Susan Howe, Peter Gizzi, David Bromige, Bruce Andrews and Susan Gevirtz. His favorites from the past are Zukofsky, Oppen, Williams, Stein, Spicer, Duncan and Apollinaire.

Critis he deems important are Max Horkheimer, Theodor Adorno, M. Perloff,

David James, Walter Benjamin, Michael Davidson, Barrett Watten, Charles Bernstein, Ron Silliman, Bruce Andrews, Steve Evans. In describing his tastes in poetry, Alexander says, “I respond most favorably to innovative form, but not as pure utterance.” He is “interested in a poetics that reflects a commitment to leftist politics of some variety — not necessarily overtly (expository) but that raises questions of the epistemological variety.

not interested in a liberatory politics of the signifier; or pure music any more than in naively content-driven verse.”

As a critic, he aims for a reading of particular works in the context of their material conditions, poetry as a reflection /or criticism of its culture of origin. He tends to think of poetry in terms of “a Bourdieulian field of poetic production, in which participants take positions that have meaning in relation to the field as a whole. we seem to suffer from a polarization @ this point — or rather not so much a polarization, which violates the spatial metaphor, but an antagonism —wherein some sectors of the field dominate in

terms of monetary capital, recognition (by mass-market media organs) by virtue of the accessibility of their work (in terms of a middle-class view of art — largely affirmative or comprehensible in terms of that class; pretensions to universality, e.g., conforming to common sense, etc.). This is light verse, even @ its most critical, because the criticism it lodges is always given in terms of the dominant, so partially serves a recuperative function; positioned elsewhere in the field, variably antagonistic but united by their lack of /or distain for monetary capital are various innovative poetries.”

He goes on to say that “if one is concerned with the politicization of poetry, it’s important to realize the value of other kinds of work, even if one still priviledges one mode. My chief interest is less in the antagonism between poetry communities than in possible critical-rhetorical strategies characterized by the whole of poetry as a genre, both innovative;

dominant — despite the fact that, clearly, my tastes run to the former. He recommends the following for entries in the Comprepoetica Dictionary: Electronic Poetry Center (http://wings.buffalo.edu/epc), n/formation

(http://choengmon.lib.utah.edu/~calexand/nonce/), UbuWeb, Fluxus Online, Poet’s House (NYC), Misc. Proj. (Atlanta zine), Talisman (N.J. journal), Situation (D.C. zine), Impercipient Lecture Series (Providence, R.I. journal), Mirage/Period(ical) (S.F. zine), Mass. Ave. (Boston zine), lyric (S.F. zine) and Antenym (S.F. zine).

Click <a href=”http://www.reocities.com/SoHo/Cafe/1493/poem2.html”>here</a> to read naldecon series, a sample of his work.

Click <a ref=”http://www.reocities.com/comprepoetica/compoems/poem3.html”>here</a> to read Joel Kuszai’s Globigerina Ooze, Alexander’s choice of another contemporary poet’s work he likes.

Kit Austin

Poet

Austin’s street address is 814 N. Dodge Street, Iowa City IA 52245; her e.mail address is caroline-austin@uiowa; and her phone number (319) 337-6124.

She has had work published in 100 Words and River King Poetry

Supplement.

Among the contemporary poets important to Austin are James Merrill, Frank Bidart, Gary Soto and Cynthia Macdonald; among those of the past she considers important are Whitman, Dickinson, Keats, Stevens, Shakespeare, Eliot, Rilke, Cendrars, Yeats, Hardy. Edmund Wilson is the one critic she names as important to her.

She welcomes any feedback about her poetry. For a sample of it, click <a href=”http://www.reocities.com/SoHo/Cafe/1493/poem36.html”>here</a>.

For Matthea F. Harvey’s Frederick Courteney Selous’s “Letters To His Love,” a favorite poem of Austin’s by someone else, click <a

href=”http://www.reocities.com/SoHo/Cafe1493/poem37.html”>here</a>.

Maura Alia Bramkamp (BRAM camp)

Poet

(street address) 266 Elmwood Ave #307

(city&state) Buffalo, NY 14222

(e.mail address) [email protected]</p>

(affiliations/organizations)

National Writers Union, member

Italian American Writers Union, member

The Haight Ashbury Literary Journal, Lifetime Subscriber

(publication credits)

<i>The Buffalo News</i> (essays)

Amazon.com Editorial Review: <i>Welcome To My Planet: Where English is Sometimes

Spoken</i>, by Shannon Olson

<i>ARTVOICE</i> (Buffalo, NY)

Buffalo Spree (Buffalo, NY)

<i>The Haight Ashbury Literary Journal</i> (San Francisco)

<i>Switched-On-Gutenberg</i> (Internet Seattle-based)

<i>Exhibition</i> (Bainbridge Island, WA)

<i>The Woodstock Times</i> (Woodstock,NY)

<i>synapse</i> (Seattle, WA)

<i>convolvulus</i>

<i>Half Tones to Jubilee</i> (Pensacola, FL)

Signals (Olympia, WA)

tight (Guerneville, CA)

Spillway (WA)

The Healing Woman (CA)

The Wise Woman (CA)

105 Magazine (New Paltz, NY)

POETALK (CA)

<i>cups: a cafe journal</i> (San Francisco, CA)

<i>Arts Journal</i>poems & interview (Poulsbo, WA)

<i>Coffee House Quarterly</i> (CO)

<i>Higher Source</i> (Bainbridge Island, WA)

And others………

(list of works)

CHAPBOOK

<i>Resculpting</i> (Paper Boat Press,1995)

ANTHOLOGIES

<i>This Far Together</i> (Haight Ashbury Literary Journal, 1995)

<i>Go Gently</i> (The Healing Woman, 1995)

<i>Bay Area Poets Coalition 1995 Anthology</i>

<i>Husky Voices</i> (Univ of WA, MFA Anthology, 1998)

(where written up)</p>

<i>Women’s Work</i> (Seattle,WA, 1995)

<i>Arts Journal</i> (Poulsbo, WA, 1996)

<i>The Healing Woman</i> (1996)

<i>Small Press Review</i> (Pick of the Month & Review, 1996)

<i>synapse</i> (review, 1996)

<i>The Kitsap Herald</i> (1995)

(contemporary poets important to Bramkamp)

Charles Simic, Jana Harris, Billy Collins, Lynda Hull (deceased),

Seamus Heaney, Lynn Emmanuel, Carolyn Kizer,

Mark Doty, Raymond Carver, Nikki Finney,

Jane Kenyon, Ai, Gillian Conoley, Patti Smith

Larry Levis (deceased), Adrienne Rich, Carolyn Forche,

Yusef Komunyakaa, Nuala Ni Dhomhnaill, Nancy Willard,

Richard Hugo, Theodore Roethke, Carol Ann Duffy,

Marlene Nourbese Philip & many others

(poets of yesteryear important to respondent)

Colette, Muriel Rukeyser, Paul Celan,

Rilke, Rimbaud, Edward Lear, Sylvia Plath,

Anne Sexton, Elizabeth Bishop,

Samuel Beckett, Eugene O’Neil, W.H. Auden, Frank O’Hara

And many more……….

(critics important to respondent)

Eavan Boland, bell hooks, Adrienne Rich…

otherwise, not particularly interested in criticism. I think going through an MFA program

ruined it for me.

(tastes in poetry) I’m most drawn to narrative, lyrical, and prose poetry. Yet, I

read widely and try to sample styles outside my usual references.

(impression of contemporary poetry) Ever-changing. Expanding, shouting, fighting

amongst our many selves, loud, soft, chilling,consoling, alienating & inviting.

(zines, etc., that ought to be listed in the dictionary)

<i>Switched-On-Gutenberg</i> (Internet)

<i>The Cortland Review</i> (Internet)

<i>SketchRadio.com</i> (Internet)

<i>Small Press Review & Small Magazine Review</i> (Dust Books)

<i>The Directory of Poetry Publishers</i> (Dust Books)

<i>Directory of Literary Magazines</i> (CLMP)

.

<b>Michael Basinski, Poet</b>

Basinski lives at 30 Colonial Avenue, Lancaster NY 14086; his

e.mail address is [email protected]; his phone number 716 645-2917

He was born 19 November 1979 in Lisbon. He is 6 feet tall and weighs 165 pounds. His

eyes and hair are brown, his ethnic background Polish. He got his Ph.D. at SUNY,

Buffalo. His occupation, says he, is working, his vocations, etc. His characterizes himself

a pagan in both religion and politics. He claims not to enjoy anything in the arts besides

poetry, or have any interest in sports. He enjoys nothing in science or philosophy, either.

In answer to the <i>Comprepoetica</i> survey question that asks a respondent to name

the first poem that comes to his mind right then, he said, None.

Basinski has published in many periodicals including <i>First Offense, First Intensity,

Angle, Torque(Toronto), Kiosk, Essex Street, Washington Review, Chain, Boxkite,

Leopold Bloom, Taproot, Generator, Arras, Explosive Magazine, RIF/T, Yellow Silk,

Benzine, Sure, Another Chicago Magazine, Lyric&, Mirage no.4(Period)ical, Lower

Limit Speech, Juxta, Wooden Head Review, Synaesthetic, Small Press Review</i>, and

other WEB and Email magazines.

His books include: <i>[Un-Nome]</i>, The Runaway Spoon Press; <i>Idyll</i>, Juxta

Press; <i>Heebee-jeebies</i>, Meow Press; and many others. He has been written up in

<i>Texture, Small Press Review, Taproot Reviews, Exile, Poetic Briefs</i>, etc.

He says that the poets of yesteryear important to him are Those before the coming of

circles. His tastes in poetry? Glitches and witches. His impression of contemporary

poetry? Angels and beasts.

<b>David Beaudouin, Poet</b>

Beaudouin resides with his wife, family and Dawgs at 2840 St. Paul St., Baltimore, MD

21218. His e.mail address is [email protected], his phone number is 410-467-0600. He

was born 3 February 1951 in Baltimore.

Beaudouin got his degree in 1975 from Johns Hopkins. His religion is Quakerism, his

main political belief, Keep right except to pass.

His credits include the following chapbooks:

<i>Catenae,

American Night,

Human Nature</i> and <i>

Gig</i>. He was last published on the Net in <i>Enterzone</i>.

Contemporary poets of importance to him are

Bernard Welt,

Terry Winch,

Kendra Kopelke,

Kim Carlin,

Jenmny Keith,

Ron Padgett and

Anselm Hollo. Earlier poets of importance to him are

Frank O’Hara,

Charles Olson,

Joe Cardarelli, and

Elliott Coleman.

About contemporary poetry, he says, Well, it’s a mess, but I’m not

cleaning it up this time.

He enjoys going to the movies<i>any</i> movies. He sums up his background in

philosophy and science with the following single sentence: When I was 10, I invented the

Buddha in my bedroom.

About his life, he says, Well, it seems to be moving along.

.

.

.

<b>Thomas Bell, Poet</b>

Bell lives at 2518 Wellington Pl., Murfreesboro, TN 37128. His telephone number is

(615)

904-2374; his e.mail addresses are [email protected] and [email protected].

Born 18 February 1943 in Milwaukee, he is married and has two children. He is right-

handed; about this he says, I write right and draw left. poetry depends on where

i’m coming from. i right write and draw to an inside straight.

He describes his religious denomination as democrat. His occupation is

psychologist, for which he got the necessary degrees from the University of Wisconsin –

Milwaukee, Marquette, and the Wisconsin School of Professional Psychology. He is also

an

editor and librarian. He’s had work published on

paper and on the Internet.

One contemporary poet who is especially important to him is Allen Davies, and he

considers William Carlos

Williams the most important poet of the past for him. He names no critics he favors

but throws his support to those who are experimental experiential.

Click<a href=”http://www.reocities.com/SoHo/Cafe/1493/poem24.html”> here</a> to

read The Flowers, one of Bell’s poems.

Visit <A HREF=”http://www.public.usit.net/trbell”>Bell’s HomeSite</a> for

more of his poems.

<b>Ken Brandon, Poet</b>

Ken Brandona painter as well as a poet (actually, both combined, much of the time)was

born 10 February 1934 in Seattle, Washington. He now lives with his wife, Maru Bruno

Flores, in Mexico. His mailing address is La Danza 6, San Miguel de Allende, GTO.

37700 Mexico; his phone number is (Mexico)(415)-2-7098. A graduate of the University

of Washington in Seattle, he has three children: Ansel, Mateo and Dylan.

According to the <i>Comprepoetica</i> survey form he filled out,

Brandon makes his living under dim eyes passes the trail market. His religion is Zenjoko,

his political affiliation good. As for the poets who have influenced him,</p>

<pre>

the other poets

I throw in the fire

to get hot

</pre>

His hobbies are confidential. In answer to the survey question about what techniques and

subject matter are of value to him in poetry, he says, Technique is self without trying for

any subject matter. Regarding contemporary poetry, he says, As I think of it, it defines

itself automatically.

Brandon is a publisher who has put out 19 issues of the zine, <i>Iz Knot</i>, as of 1997.

His work has not been much written up. My own stuff grips my interest, he says in

response to the query on the survey about what books he reads, or movies he goes to, and

so forth. He describes his background in philosophy and science as normal. As for the

sports he watches or participates in, information about that, he says, is confidential.

On life-in-general, Brandon says:</p>

<pre>

finding his path less taken

misled the dead gardner

for a while

</pre>

To view an untitled sample poem by Brandon, click <a

href=”http://www.reocities.com/SoHo/Cafe/1493/poem31.html”>here</a>. </p>

<b>Janet Buck</b>

Buck teaches writing and literature at the college level. Her poetry, humor, and

essays have appeared in <i>The Pittsburgh Quarterly, The Melic Review, Sapphire

Magazine, The Recursive Angel, Southern Ocean Review, Lynx: Poetry from Bath,

Apples & Oranges, Oranges & Apples, The Rose & Thorn, San

Francisco Salvo,

Poetry Super Highway, Poetik License, Mind Fire, Astrophysicist’s Tango

Partner

Speaks, Perihelion, Oracle, Poetry Motel, Feminista!, Calliope, The Beaded

Strand,

New Thought Journal, Medicinal Purposes, 2River View, Kimera, Free Cuisinart,

In

Motion, Athens City Times, Conspire, Idling, remark, BeeHive, Gravity,

AfterNoon, A

Writer’s Choice, Niederngasse, Shades of December, Maelstrom, The Oracular

Tree,

Red Booth Review, Poetry Heaven, Tintern Abbey, Arkham, hoursbecomedays, The

Artful Mind, Oatmeal & Poetry, Black Rose Blooming, Apollo Online, Masquerade,

Pigs ‘n Poets, Savoy, The Poet’s Edge, Allegory, GreenCross, Online

Writer,

Poetry

Cafe, Oblique, Locust Magazine, The Poetry Kit, Pyrowords, Vortex, Ceteris

Paribus,

The Suisun Valley Review, Illya’s Honey, Fires of Autumn, Orbital Revolution,

A

Little Poetry, Dead Letters, King Log, Peshekee Review, The Green Tricycle,

Pogonip,

Chimeric, Poetry Repair Shop, 3:00 AM Magazine, Wired Art from Wired Hearts</i>,

and

hundreds of print journals and e-zines world-wide. A print collection of

Janet’s poetry

entitled <i>Calamity’s Quilt</i> is soon to be published by Newton’s Baby Press.

For a sample of her poetry, A Writer’s Prayer, click <a

href=”http://www.reocities.com/SoHo/Cafe/1493/poem49.html”>here</a>.

<b>Bill Burmeister (BER my stir), Poet</b>

Burmeister resides with his wife, Diana, at 8018 Lakepointe Drive, Plantation, Fla 33322.

His

e.mail address is [email protected]. A Florida native of Armenian

(mother) and German (dad) descent, he was born 22 March 1961, in St. Petersburg. He

works as an Electronics Engineer, having gotten his bachelor’s and

master’s in that field at the University of Central Florida. His hobbies include

reading folklore, following baseball, listening to jazz/blues music, raising plants, amateur

astronomy, good wine and cigars, and collecting stamps.

He has several works in progress (as of late October 1997): poem/play (1 yr); first

chapbook of poems; translations of a play by the (deceased) Ecuadorian poet Gonzalo

Escudero and poems from Jorge Guillen’s <i>Cantico</i>.

Among the contemporary poets important to Burmeister are

John Ashbery, Charles Bernstein, A. Child, Clark Coolidge, Henry Gould, Lyn Hejinian,

Simic, J. Tate, Revell, Paz, Yau, L.Scalapino, B.Hillman, S.Howe, D.Ignatow, M.Strand,

M.McClure, B.Guest, R.Bly . . .

Earlier poets important to him include Homer, Dante A., Milton, Shakespeare, Blake,

Wordsworth, Dickinson, Rimbaud, Apollinaire, Loy, Williams (WCW), Pound, Breton,

Char, Zukofsky, Oppenheim.Celan, Loy, Joyce, T.Roethke, Carroll, Jorge Guillen, Lorca,

Neruda, Gonzalo Escudero, Spicer, Duncan, Patchen, Antonio Machado, Dickinson,

Wallace Stevens, Unamuno, Gustavo Adolpho Bequer, Beckett, D.Thomas, Muriel

Rukuyser, Rilke, J.Taggart . . .

Among critics, he particularly values the work of Blanchot, Bernstein, Perloff, Sartre,

Bachelard and Paz.

About his tastes in poetry he says, I have a fairly open, generous approach to poetry,

especially in what comes to me from the past. For poetry in the present, I look for the

writing as thinking, metaphysical, meditative, stream of consciousness, chance, new

surrealism, playfulness with language, nonsense, energetic lively language, reinvented

language, and so on. I look for innovation, but not necessarily formal innovation. What I

like most, I get from the avante-garde, but contentment with the avante-garde is an

impossibility by definition. The avante-garde is not the beginning and the end of a

particular kind of poetry, but rather only the beginning, and maybe not the best possible at

that since a new dialogue has been begun with all of literature and history, the past as well

as a future.

As for criticism, he says, I don’t consider myself a critic as such, although

naturally, I recognize the importance of maintaining a critical ability since this has been

and will continue to be an essential part of literature. For me, taste, appeal, enjoyment,

and enthusiasm must be considered at the personal level as much as any aesthetic, but can

never be

forced upon another as aesthetic. I tend to believe that poetry

is a lot like religion in that a kind of faith is necessary to

hold the poem together. It seems to me that the poem is a delicate, but patient entity that

outlives time-sensitive criticism (such as identity politics and other socio-political agendas

in the guise of criticism). Good critical writing is that which goes before or after good

writing: it informs, enlightens, and expands readership rather than merely decodes and

justifies.

Outside his field, Burmeister enjoys reading novels by James (<i>The Wings of a

Dove</i>), Faulkner (<i>The Sound and the Fury</i>) Kafka (<i>The Trial</i>) Gunter

Grass (<i>Cat and Mouse, Tin Drum</i>), Thomas Mann (<i>The Magic Mountain</i>),

the science fiction of G.Bear, Simak, Asimov, and D.Brin (before he choked), and Plays

by Beckett (<i>Waiting for Godot, Krapp’s last tape</i>), Gonzalo Escudero

(<i>Parallelogram</i>), the short word plays of Gertrude Stein, and the plays of

Sheakespeare. He collects books of black & white photography (Weston, Man Ray,

Irina Ionesco) and films (Wells, The Marx Brothers, D.Lynch and more). He is also

building a collection of original paintings by Latin American painters such as the

contemporary Ecuadorian Arauz. He listens to John Cage, experimental jazz (A.Braxton

and others) and acid jazz, and classical music.

About his interests in science and philosophy, he says, i tend (right now anyway) to be

partial toward the Spanish philo. Jose Ortega y Gassett, J.P.Sartre, Kierkegaard, Derrida,

& Kant.

For philosophy of science, I have tended toward Einstein, Newton, Asimov, and Faraday.

Burmeister was educated in hard sciences up through elementary modern physics (theory

of quantuum electrodynamics, statistical mechanics, etc.), in mathematics

up through essential calculus, linear operator theory, diffential equations and boundary

value problems (applied).

In answer to the <i>Comprepoetica</i> survey question about the present world situation,

he says, I’m wondering for how long we can survive this ludicrous zero-sum game

known as the ‘Global economy.’

For a sample of Bill Burmeister’s poetry (with a brief commentary on it by

Burmeister), click <a

href=”http://www.reocities.com/soho/cafe/1493/poem11.html”>here</a>.

<b>Harry Burrus, Poet/Publisher</b>

Burrus lives with his wife, Megan, at 1266 Fountain View, Houston, Texas 77057-2204.

His telephone number is (713) 784-2802; his e.mail address, [email protected]

He was born in Denver, reared in St. Louis. Moved to Houston in June 1977. He is six

feet one and weighs 175 pounds. His parents

were university professors. His father was the first Pro Football player with a PHD. He

himself holds advanced degrees in Film, Dramatic Arts, and Poetryand is active as a

collagist, photographer, screenwriter and filmmaker as well as a poet and the publisher of

<i>O!!Zone</i>, which he describes as a

modest literary-art zine.

His poetry books include: <i>I Do Not Sleep With Strangers, Confessions of a Tennis

Pro;

Bouquet; A Game of Rules; Without Feathers; For Deposit Only; the Jaguar

Porfolio</i>; and <i>Cartouche</i>. He has also co-edited with Peter Gravis of Black Tie

Press,

<i>American Poetry Confronts the 1990’s</i>.

Burrus’s poetry, photographs, and collages have appeared in various publications

and

exhibitions in the US and abroad.

Says Burrus about making a living, I gain dinero via photography, scripts, workshops, and

various other artistic

pursuits (and years ago as a tennis pro).

About religion and politics/nationalism (and money), he finds that most people

cannot discuss without harboring ill-feeling and/or distrust for those who

possess views different from their own. Hence, I tend not to engage in these

areas unless it is with those capable of out of body experiences.

He has difficulty specifically determining what poets and critics and other influences have

been important to him. The aggregation is subtle and ongoing. Travel, for sure, is a

primary player. On the goat path and with the

aroma of donkey dung filling the surrounding air, I witness and pick up

juxtaposition, impact, resonance, and cultural unravelings. On these

excursions I shoot a lot of film, make journal entries, and ambient sound

recordings and always use the material. I never know how or when or in what

form the work will appear, but it eventually does pop up somewhere, either in

poems, art of some kind like a collage, or, perhaps, a story emerges.

I am drawn to openness, curiosity, and a willingness to take chances. I like

strong personalities. I favor high energy and experimentation. The seduction

has been more from artists and filmmakers, rather than poets, although a few

poets have landed a stroke or two. A few personalities that quickly come to

mind are: Ernst, Magritte, Man Ray, Buñuel, Resnais, Cartier-Bresson,

Schwitters, Godard, Bergman, Newton, Rausenberg, Matta, Isidore Ducasse,

Pessoa, Prevert, Bowles, Wenders, and Gysin.

I tend to appreciate those engaged in multiple activities and skilled in

different pursuits. Peter Beard and Bruce Chatwin come to mind. Journeymen.

I enjoy Henry Miller’s writing about watercolors more than his novels. I

enjoy the independence of his watercolors.

I make extractions from movements (Dada, Surrealism, The Beats, etc.), pulling

on the dynamism or a particular tack something I notice that I might employ

in my work. I may utilize or value aspects of the thinking that goes into a

work more than the work itself. Burroughs’ and Kerouac’s and Lawrence’s

ideas, for example. I also value their dedication.

Previously I read a lot of poetry and poetry publications, but I became

disenchanted with the likes of APR and Poetry too much sameness. Even

newcomers and alternative journals, which broke away from the writing school

content and were, at first, exciting and fresh, even they slowly lost their

zest and started wearing that familiar uniform. There is, however, still

energy in various zines and micro-presses, so, choice is out there. One must

forage for the interesting which is the same with people.

My engagement with international visual poets, mail artists, and photographers

provides visual stimulation, plus insights into other cultures. Myriad

personalities have opened to me and my exchange with them I eagerly maintain.

I find correspondence or working on a collage or making a photograph more

intriguing than being a spectator of some sporting event.

Burrus cites three critics who write well about their topics: Walter Pater, John Simon, and

Marvin Bell.

The last full collection of poetry Burrus has read (as of 15 November 1997 was

Bukowski’s <i>Betting on the Muse</i>; last

non-poetry book: <i>Breaking the Maya Code</i>, by Michael Coe.

Click <a href=”http://www.reocities.com/SoHo/Cafe/1493/poem18.html”>here</a> to see

Blue Mirror, a poem from Burrus’s <i>A Game of Rules</i>

(name of respondent) Brandon

(pronunciation of respondent’s name) Carpenter

(street address) 4616 S. Rusk

(city&state) Amarillo, Tx 79110

(e.mail address) [email protected]

(phone number) N/A

(po-type) Poet/Critic

(affiliations/organizations)

Denver Word Affiliate

Vocal Velocity Records

(publication credits)

Poetry Cafe

Anvil

Poetry Shelter

Pauper.com

Sharptongue

(list of works)

A flame of the heart in the hands of Dread

Discombobulate the Dissemated

Muddy’s Cafe: Out of the Mud

Sharptongue

(contemporary poets important to respondent) Ben Ohmart

(poets of yesteryear important to respondent)

Baudlelaire

Rimbaud

Ginsberg

Kerouac

(tastes in poetry)

Avant-Garde

Beat

(description of criticism) Pick out the truth of the piece, show the path to find these truths

and uplift the reader, author, editor and other critics.

(zines, etc., that ought to be listed in the dictionary)

Realpoetic

(sample of respondent’s poetry) members.tripod.com/Carpenter_B</p>

<hr />

</body>

</html>

.

<b>Joel Chace, Poet</b>

(pronunciation of respondent’s name) Chase

(street address) 300 E. Seminary St.

(city&state) Mercersburg, PA 17236

(e.mail address) [email protected]

(phone number) 717-328-3824

(affiliations/organizations)

Poetry EditorAntietam Review and 5_Trope electronic

magazine.

(publication credits)

My poems have appeared or are forthcoming in print journals and

magazines such as the following: <i>The Seneca Review, The Connecticut

Poetry Review, Spinning Jenny, Poetry Motel, No Exit, Pembroke

Magazine, Crazy Horse, Kudos</i> (England), and <i>Porto-Franco</i> (Romania). I

have also published work in Electronic Magazines such as the following:

<i>Ninth St. Labs, Recursive Angel, Highbeams, Switched-on-Gutenberg,

Kudzu, Pif, The Morpo Review, Snakeskin, Slumgullion, PotePoetZine,</i>

and <i>The Experioddicist</i>.

(list of works)

Northwoods Press, in 1984, published my collection of poems entitled

<i>The Harp Beyond the Wall</i>. Persephone Press, in 1992, published my

second book, <i>Red Ghost</i>, which won the first Persephone Press Book Award

and was nominated for a Pushcart Prize in that same year. Big Easy

Press, in 1995, brought out a collection entitled <i>Court of Ass-Sizes</i>.

In June, 1997, came a full-length collection, <i>Twentieth Century

Deaths</i>, from Singular Speech Press. <i>The Melancholy of Yorick</i>

(Birch Brook Press) and <i>maggnummappuss</i> (nominated for a 1998 Pushcart Prize)

appeared in 1998, and a bi-lingual edition of my poems is being prepared in Romania.

(where written up)

<i>Slumgullion, Pif, Mind Fire, A Writer’s Choice, Next,

No Exit, Grab-a-Nickel, Small Press Review</i>.

(contemporary poets important to respondent)

Jake Berry, W.D. Snodgrass, Adrienne Rich,

Jack Foley, Robert Creeley.

(poets of yesteryear important to respondent)

Jack Spicer, Thomas McGrath, Muriel Rukeyser,

Wallace Stevens, Walt Whitman.

(critics important to respondent)

Jack Foley, Muriel Rukeyser,

Marjorie Perloff.

For two samples of Chace’s poetry, click <a

href=”http://www.reocities.com/SoHo/Cafe/1493/poem48.html”>here</a>. He’d

appreciate any feedback on it that you’d care to e.mail him.

<b>Blaise Cirelli, Poet</b>

Cirelli was born 1 January 1952 in Philadelphia. He describes himself as having a

Buddhist leaning and being Leftist Apolitical. His publication credits include

<i>Agniezewska’s Diary, VIA, Zaum, Blind Donkey </i>and<i> Talus and

Scree</i>, and his

etry’s been written up in the San Louis Obispo Local newspaper. Contemporary

poets he admires include Michael Palmer,

Lyn Hejinian, Mei Mei Bruseenbugge (spelling?), Robert Hass, Ron Padgett and Robert

Pinsky. He also admires the work of Ezra Pound,

Homer,

William Carlos Williams,

Loraine Niedecker,

Frank O’Hara,

Shelley,

Browning and

Tennyson.

Critics important to him are

Charles Altieri,

Helen Vendler,

Marjorie Perloff and

Forest Gander.

As a reader of poetry, he enjoys Experimental, Meditative Lyric poetryand <i>not</i>

Nature (Because how can you not like nature? I’d rather be in nature than read

about it). His impression of the current scene is that There seem to be a lot of

diocre poets getting published.

Among his favorite books are: <i>The Brothers Karamazov, Crime and Punishment

<i>and</i> The

Sorrows of Young Werther</i>. He lists two favorite movies: <i>Black Robe</i> and

<i>Il Postino</i>. The sculpture of Henry Moore is important to him. About philosophy

he says, I wish I could understand Wittgenstein. On life-in-general: Some peop

are born with failure, others have it thrust upon them. His

Favorite name for a cat: Spot (if it has spots); Favorite food: organic turnips.

For a sample of Cirelli’s poetry click <a

href=”http://www.reocities.com/SoHo/Cafe/1493/poem4.html”>here</a>.

<b>Dark Poet, Poet</b>

Dark Poet’s address is 555 this isn’t real, Punta Gorda FL 33982. His

e.mail address is [email protected], his phone

number,(941) 555-9992.

(affiliations/organizations) NA

(publication credits) NA

(list of works) NA

(where written up) Conspiracy boards all over

(contemporary poets important to respondent) na

(poets of yesteryear important to respondent) Poe

(critics important to respondent) na

(tastes in poetry) na</p>

You can find a sample of Dark Poet’s work by clicking <a

href=”http://www.reocities.com/SoHo/Cafe/1493/poem45.html”>here</a>. His attitude

toward getting feedback on it: Sure. It’s a rough draft.

<b>Catherine Daly (DAY lee), Poet</b>

Daly lives at 533 South Alandele Avenue, Los Angeles CA 90036.

Her e.mail address is [email protected], and is affiliated with

UCLA Extension and various listservs.

So far (late 1998), Daly has gotten about 80 poems into print but has not yet had a book

published. She has the following

manuscripts sitting around her house, however: <i>Engine No. 9, Locket, Manners in the

Colony, Dark Night</i>, and <i>The Green Hotel</i>.

The work of Barbara Guest and some of that of Barbara Hillman

has been important to her, and she likes the work of Todd Baron, Spencer Selby, Karen

Volkman, Ann Lauterbach (her favorite poetry teacher), Janet Holmes, Jeanne Marie

Beaumontthe last three of

whom have been especially supportive of her efforts.

She considers the usual suspects among the poets of yesteryear

important to her, and she admires the criticism of Susan Howe.

About poetry she says, I expect a great deal of thought and feeling to be behind a poem,

and I tend to like poems which reflect ideas. Because I studied religion and philosophy

and math, I am particularly sensitive to the misuse of many ideas commonly placed into

these categories.

She likes her poetic narration true, not fictional.

A critic as well as a poet, Daly prefers to express critically what (she feels) the poet

attempts vs. succeeds at doing. For example, she says, Wallace Stevens mentioned that it

was really what he attempted that pleased him about his work, but that he never achieved

anything near that in his poetry. For a sample

of her criticism, her first book review, an impression of contemporary poetry, can be

found in <i>American Letters & Commentary</i>, 10th Anniversary issue.

She thinks the American Contemporary Poetry ’scene’ is very much like

the alternative music scene of the 80s, and perhaps what the truly alternative music scene

still is: an incredibly generous but fragmented variety of subgenres waiting for someone

like Kurt Cobain to come along and steal all of the riffs and jam them together on a

national stage.

See Daly’s web site for links to poems of hers that have been published online:

http://members.aol.com/cadaly.</p>

<b>Michel Delville (del VIL), Critic</b>

(pronunciation of respondent’s name) [delvil]

Delville lives at Alllée du Beau Vivier 38, 4102 Seraing, Belgium. His e.mail address is

[email protected]; his phone number is ++ 32 4 3374386.

He has two books coming out in 1998: <i>The American Prose Poem: Poetic Form and

the Law of Genre</i> (Gainesville FL: UP of Florida), and <i>J. G. Ballard</i>

(Plymouth: Northcote House).

He considers the following contemporary poets of importance:

Henri Michaux, Ron Silliman, Vasko Popa,

Miroslav Holub, Francis Ponge, Madeline Gins,

Paul Nougé, Pierre Reverdy, Max Jacob, Pierre Alferi,

John Cage, Peter Redgrove and Rosmarie Waldrop.

As for poets of the past, he lists Arthur Rimbaud, Stéphane Mallarmé, Charles Baudelaire,

Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, Sappho, Oscar Wilde, Shakespeare, Milton and Dante as

the heavyweights for him.

He notes four critics as being important to him: Marjorie Perloff, Roland Barthes, Frank

Lentricchia and Gérard Genette.

<b>Debra Di Blasi, Poet</b>

(pronunciation of Di Blasi’s name) dee BLAH-see

Di Blasi’s mailing address is 5932 Charlotte St., Kansas City, MO 64110, her

e.mail address is [email protected].

(affiliations/organizations)</p>

Missouri Arts Council Literature Panelist

PEN Center USA West Member

The Authors Guild, Inc. Member

The Academy of American Poets Associate Member

The Writers Place Member

National League of American Pen Women, Westport, MO Branch

Member Chair, Short Story Committee</p>

publication credits

BOOKS:

* <i>Drought & Say What You Like</i>, novella, New Directions Books: New

York, NY. March 1997 winner Thorpe Menn Book Award

* <i>Prayers of an Accidental Nature</i>, short story collection, Coffee House Press:

Minneapolis, MN. May 1999.

* Gass Pain, hypertext essay (Dalkey Archive Press/The Center for Book Culture,

www.centerforthebook.org)

*many published short fiction, articles, essays, reviews

list of works

FICTION

* <i>What the Body Requires</i> (formerly titled <i>Reprise: Reprisal</i>), novel (See

AWARDS)

* <i>The Fourth Book</i>, short story collection, in progress</p>

SHORT STORIES

*Czechoslovakian Rhapsody Sung To The Accompaniment Of Piano. <i>The Iowa

Review</i>. December 2000 (See RADIO / AUDIO and PERFORMANCE /

INSTALLATION / THEATRE)

* Blue, Recollection, and Exiles. <i>The Prague Review</i>. Winter 2000

*Snapshots: A Geneology. Show + Tell anthology of Kansas City writers and artists,

Potpourri Publications: Kansas City, MO. June 2000

*The Buck. Potpourri literary journal. Fall 1996

*Blind. New Letters literary journal. Spring 1996

*Drowning Hard. Cottonwood literary journal. 1995 anthologized in Moondance e-zine.

1997

*I Am Telling You Lies. Sou’wester literary journal. 1995

*Chairman of the Board. TIWA (Themes Interpreted by Writers and Artists) literary and

visual arts magazine. 1993 (See RADIO / AUDIO)

*An Interview With My Husband. New Delta Review. 1991 anthologized in Lovers:

Writings By Women, The Crossing Press. 1992. (See AWARDS)

*Delbert. <i>AENE literary journal</i>. 1991

*The Season’s Condition. Colorado-North Review literary journal. 1990 (See

FILM and RADIO / AUDIO)

*Where All Things Converge. Transfer literary journal. 1989</p>

NONFICTION

*<i>The Way Men Kiss</i>, memoir, in progress

<i>Gass Pain</i>, hypertext, The Center for Book Culture casebook on William H.

Gass’s The Tunnel, H.L. Hix, editor. November 2000

(www.centerforbookculture.org)</p>

Essays

Millennium Garden: Paintings by Jim Sajovic. Published in art catalog. September 1999.

Out of the Garden, Into the Cave. 1997 (See AWARDS)

What Three Cheers Everywhere Provide. Anthologized in Exposures: Essays By Missouri

Women, Woods Colt Press: Kansas City, MO, March 1997 (See AWARDS)</p>

Articles (for SOMA arts magazine: San Francisco, CA)

We’ve Got Joe Montana. 1994

I Am Writing To You From the Middle Of Nowhere. 1990

James Rosenquist: Seeing/Not Seeing. 1990

Diamanda Galas: Honesty Inside A Clenched Fist. 1989

Rising From the Ash Heap of Performance Art, Rinde Eckert Takes Off. 1988

Otto Hitzberger: Cutting Away. 1987

Miró. 1987

Jonathan Barbieri: Missiles Across the Border. 1987</p>

Art Reviews (for <i>The New Art Examiner</i>: Chicago, IL)

Jane Ashbury. 1985.

Marilyn Propp. 1984,</p>

SCREENPLAYS / FILM

Screenplays Produced</p>

<i>Drought</i>, 16mm, 28 min. 1998 (premiere) 1993 (written)

Based on the novella of the same title by Debra Di Blasi.

Produced by Breathing Furniture Films/Lisa Moncure & Michael Leen,

Screenplay by Debra Di Blasi, Lisa Moncure, Michael Leen, Directed by Lisa Moncure,

Photography by Michael Leen, Sound Design by Jim McKee/Earwax Productions,

Starring Jessika Cardinahl & Jack Conley, Production esign by Megan Ricks

& John Matheson, Editing by Jennifer Jean Cacavas, Radio Program Music by

Allen Davis.</p>

SCREENINGS:

o National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC, November 2000

o Ragtag Cinema: Columbia, MO. June 2000

o Universe Elle, as part of the 53rd Cannes International Film Festival: Cannes,

France. May 2000

* Broadcast rights purchased by Independent Film Channel. Premiere broadcast

November 23, 1999

* Kansas City Filmmakers Jubilee: Kansas City, MO. April 1999 (see AWARDS)

o Göteborg Sweden Film Festival: Göteborg, Sweden. Feb. 1999

o Festival Internacional de Cine de Bilbao Spain: Bilbao, Spain. November 1998

o Sao Paulo Mostra Internacional de Cinama: Sao Paulo, Brazil. October 1998

o Figueira da Foz International Festival of Cinema: Lisbon Portugal. September 1998

(See AWARDS)

o Webster University Film Series: St. Louis, MO. September 1999.

o Sarajevo International Film Festival: Sarajevo, Bosnia. August 1998

o Recontres Cinemágraphiques Franco-American D’Avignon, France:

Avignon, France. June 1998 (See AWARDS)

o Charlotte Film Festival: Charlotte, NC. June 1998

o Toronto Worldwide Short Film Festival: Toronto, Canada. June 1998 (See

AWARDS)

o New York/Avignon Film Festival: New York, NY. April-May 1998

o New York Women’s Film Festival: New York, NY. April 1998

o Taos Talking Pictures Film Festival: Taos, NM. April 1998 (See AWARDS)

o American Film Institute Film Festival: Los Angeles, CA. World premiere: October

1997 </p>

<i>The Season’s Condition</i> — Super 8, 10 min.

Based on the short story of the same title by Debra Di Blasi.

Produced and directed by Lisa Moncure, photography by Michael Leen. </p>

SCREENINGS:

o Toronto Film Festival: Toronto, Canada. 1998

o American Film Institute Film Festival: Los Angeles, CA. 1995

o Bay Area Film & Video Poetry Festival: San Francisco, CA. 1994

o Culture Under Fire Film Festival: Kansas City, MO. 1994</p>

Screenplays in Pre-Production

<i>My Father’s Farm</i>, original short documentary in pre-production, based on the

essay Out of the Garden, Into the Cave by Debra Di Blasi. Produced/written/directed by

Debra Di Blasi.

<i>Intruder</i>, short screenplay in pre-production screenplay by Debra Di Blasi.

Producer/director Edward Stencel.</p>

Screenplays Unproduced

The Hunger Winter, original feature in progress co-written with historian Hal Wert

The Shortest Route Home, original short screenplay

The Walking Wounded, original feature-length screenplay (See AWARDS)

The Significance of Dreams, original short screenplay

Taming Wild Geese — unproduced original feature-length screenplay

Staring Into The Sun — unproduced original feature-length screenplay </p>

RADIO / AUDIO</p>

<i>Czechoslovakian Rhapsody</i>, radio adaptation from the short story of the same

title. Produced by Finnish Broadcasting Corporation (YLE): Helsinki, Finland.

Broadcast premiere October 1998

Kansas City Fiction Writers: Vol. 1 — short stories (The Season’s Condition and

Chairman of the Board) recorded for double CD set, limited edition featuring Kansas City

fiction writers. Art Radio: Kansas City, MO. Release date December 1998

Dreamless Dream, radio adaptation from the short stories Blind, Stones, and Our

Perversions. Produced by Finnish Broadcasting Corporation: Helsinki, Finland.

Broadcast premiere October 1998

An Interview With My Husband — chamber theatre adaptation from the short story of

the same title by Debra Di Blasi. Produced and adapted by Stephen Booser, directed by

Art Suskin, stage management by Nancy Madsen, premiere at The Writers Place, Kansas

City, MO, October 1997

Drought — radio adaptation of the novella of the same title by Debra Di Blasi, produced

and adapted by YLE (Finnish Broadcasting Corporation), Helsinki, Finland o broadcast

premiere May 1998</p>

PERFORMANCE / EXHIBITIONS / THEATRE</p>

Unbroken View, multimedia installation collaboration with visual artist Sharyn O’Mara

assisted by sound designer Chris Willits. Premiere exhibition: Edwin A. Ulrich Museum:

Wichita, KS. November 2000-January 2001. Traveling to Juniata Landscape Museum:

Juniata, Pennsylvania. September 2001.

Czechoslovakian Rhapsody, multimedia performance based on the short story of the same

title by Debra Di Blasi. Written/directed/produced/performed by Debra Di Blasi.

Premiere Ragtag Cinema, June 2000

An Interview With My Husband — chamber theatre adaptation from the short story of

the same title by Debra Di Blasi. Produced and adapted by Stephen Booser, directed by

Art Suskin, stage management by Nancy Madsen, premiere at The Writers Place, Kansas

City, MO, October 1997</p>

(where written up)</p>

<i>The New York Times Book Review

*Publishers Weekly

*Book Forum

*ForeWord

*In Print

*The Kansas City Star</i>

many, many others</p>

contemporary poets important to Di Blasi</p>

Louise Gluck

Larry Levis (deceased)

Billy Collins

H.L. Hix

Galway Kinnell

Mark Strand

Marilyn Hacker

many, many others

poets of yesteryear important to Di Blasi

Sylvia Plath

T.S. Eliot

W.B. Yeats

many, many others

critics important to Di Blasi: Not particularly interested in criticism

tastes in poetry: As a fiction writer, I am most fond of narrative poetry, although I enjoy

anything brilliant that contains aural lyricism. Content is important only in that it helps

illuminate a ‘truth’ I already know or confronts me with one I have not yet

discovered.

impression of contemporary poetry: Wonderful. The range of styles and voices is a

pleasure.

zines, etc., that ought to be listed in the dictionary: Virtually every serious literary journal

that publishes poetry deserves to be on this list.