ANNOUNCEMENT

Clearance Sale

25 4″ by 3″ Runaway Spoon Books for $50, a savings of over $70, and no shipping charge. Ten full sets available at present. Send me $50 using the Paypal button below and I will ship you the following titles, many of which are or will be collectors’ items:

Fluxonyms

m. aND

Estrella

D. Baratier

Vanishing Whores & the Insomniac

G. Beining

Span

J. M. Bennett

Conflatio

J. Byrum

25 Scores

A. Bull

Light

B. Cobbing, B. Keith, P. Grenier, A Lora-Totino, H. Tanabu

Capacity X

B. DiMichel

The God-Shed

A. Falleder

This Word

H. Fischer

Heavyn

L. Gorman

An April Poem

B. Grumman

Ghostlight

G. Huth

Khwatir

J. Leftwich

Fields/Pitches/Turfs/Arenas

R. Kostelanetz

Transentence

d. lopes

Until It Changes

S-P Martin

far human character

J. Martone

Artist as Autist

J. Moskovitz

Mockingbird/ Litmus

L. Tomoyasu

Artaud What

N. Vassilakis

Cheer

D. Waber

Photo Script

P. Weinman

Night Rain

T. Wiloch

Viscosity Induction

C. Winkler

WARNING: THIS PAGE IS A PAGE-IN-PROGRESS

It will be difficult to read until I have time to get it in shape, which I expect to be doing very slowly.

The Runaway Spoon Press

Box 495597, Port Charlotte FL 33949

The information listed below is up-to-date as of Fall 2005–with titles published after Spring 2001 in red, and unaccompanied by full particulars. Prices and availability are subject to change (some titles are temporarily out-of-print, or close to it). Note: most Runaway Spoon Press Books are saddle-stitched with card-stock covers; the price of each includes postage, handling and taxes; it is, in short, the thing’s price–in US dollars, that is.

MIEKAL AND

The Quotes of Rotar Storch

Introduction by Crag Hill

A collection of avant garde collages, illustrations and poetry that playgrounds all of existence. 50 pages, 8.5″ by 11″. Publication Date: 6 November 1989. ISBN 0-926935-23-2. Price: $10

MIEKAL AND & LIZ WAS

Fluxonyms

A collection of alphaconceptual poetry or: exploratory breakdowns of polysyllabic neologies. 30 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 23 February 1989. ISBN 0-926935-09-7. Price: $5

IVAN ARGUELLES

Madonna

23 pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″. Publication Date: 22 June 1998. ISBN 1-57141-043-0. Price: $8

TOM BAER

Roller Rink

One-act play about Hollywood high-rollers. 24 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 14 May 1994. ISBN 0-57141-001-5. Price: $5

DAVID BARATIER

Estrella

Linquexpressive Poetry. 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 2002. ISBN 1-57141-059-7. Price: $5

DENNIS BARONE

Tempura Fugit

22 pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″. Publication Date: 28 June 1998. ISBN 1-57141-044-9. Price: $8

MICHAEL BASINSKI

Abzu

with visimagery by WENDY SORIN

Poems about Abzu that “previgilage mispeeling.” 8.5″ by 11″. Publication Date: 3 June 2003. ISBN 1-57141-060-0. Price: $10

The Flight to the Moon

Eight myth-based circular visual/infraverbal poems about the moon12 pages, 5.5″ by4.25″. Publication Date: 16 July 1993. ISBN 0-926935-81-X.

Price: $5

Red Rain Too

A visual poetry sequence that recreates the archaeological investigation of ancient American Indian texts. 17 pages. ISBN 0-926935-64-X. Price: $5

[Un Nome]

Magnamythic visual infraverbal poems. 26 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 24 August 1997. ISBN 1-57141-039-2. Price: $5

GUY BEINING

Inner Insights

more of Beining’s ridiculously

little-known text&graphics collages5.5″ by 8″. Publication Date:

18 July 2005.ISBN 1-57141-068-6. Price: $8

M-Factor

Wildly socio-techno-sexual adventures in

illuscription30 pages, 8.5″ by 5.5″. Publication Date: 2

July 1993. ISBN 0-926935-82-8. Price: $8

Piecemeal

Introduction by Harry Polkinhorn

A both slick and coarse, x-rated dislocational collage sequence that alleys profoundly through just about the whole of modern life and art308 pages in 8 volumes, 4.25″ by 5.5″.

Publication Dates: 17 April 1988 (volumes 1 & 2), 16 April 1989

(volumes 3 & 4), 10 December 1989 (volumes 5 through 8). ISBN

0-926935-25-9, 0-926935-26-7, 0-926935-27-5, 0-926935-28-3, 0-926935-29-1,

0-926935-30-5, 0-926935-31-3, 0-926935-32-1, 0-926935-33-X, the last being

for the set as a whole. Price per volume: $5; per set: $30

Vanishing Whores & the Insomniac

Haiku of bigCity

squalor stunningly illustrated with collages and pen&ink

drawings38 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 27 June

1991. ISBN 0-926935-57-7. Price: $5

BENNETT, ERNST, GRUMMAN, HELMES

12 Colorborations

four visual poets each collaborating oncewith each of the others in full color

8.5″ by11″. Publication Date: 17 June 2004.ISBN 1-57141-066-X. Price: $200

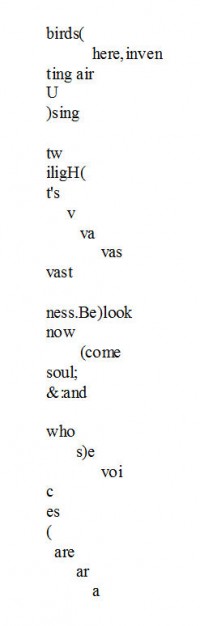

JOHN M. BENNETT

SH ONE

sample poems:

foNo act

ectic

sUre wAs

c rock an

bee p an

j erk an

lip an id

Span

Introduction by Ivan Argüelles

Demented lyrics of the everyday

39 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″; Publication Date: 20 December 1990.

ISBN 0-926935-44-5. Price: $8

spinal speech

A collection of burning poodle

poems48 pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″. Publication Date: 24 May

1995. ISBN 0-57141-013-9. Price: $8

Swelling

Visimagistic Introduction by Al Ackerman

The first Runaway Spoon Press collection of burning poodle

poetry from the originator of the genre, or: surrealism,

animal-urgent38 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 11

August 1988. ISBN 0-926935-05-4. Price: $5

JAKE BERRY

Brambu Drezi

A spectacular weave of disjunctional poetry, amuletic illumagery and ideas and images out of all known–and several other—worlds

61 pages, 8.5″by 11″. Publication

Date: 17 March 1994, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 23

February 1989. ISBN 0-926935-94-1. Price: $10

Equations

Introduction by Harry Polkinhorn

Wildly disjunctional poems about science, mythology,

human existence with wonderful accompanying illustrations by the

author43 pages, 4.25″ by 5.5″. Publication Date: 16

February 1992. ISBN 0-926935-63-1. Price: $5

CARLA BERTOLA

Interferences Suite

print&handwritten collagical

visual poem sequence.8.5″ by 5.5″. Publication Date: 4 June

2003.ISBN 1-57141-062-7. Price: $8

JONATHAN BRANNEN

Ethernity

Introduction by Dan Raphael

Shaped poems dealing somewhat dislocationally with the eternal verities of summer, the moon, language….

28 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″.

Publication Date: 29 July 1989. ISBN 0-926935-19-4. Price: $5

Sunset Beach

A sexually-charged prose montage that

swells “after-words” into summerful major visual poetry50 pages, 5.5″

by 8.5″. Publication Date: 24 June 1991. ISBN 0-926935-54-2.

Price: $50

Warp & Peace

Introduction by G. Huth

A visual poetry sequence exploring the eternal cycle of human destruction

and regeneration18 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date:

19 April 1989. ISBN 0-926935-17-8. Price: $5

JOHN BYRUM

Conflatio

Introduction by Bob Grumman

A visual poetry sequence about the branching of trees, blood vessels, axons,

language, thought itself….26 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″.

Publication Date: 14 February 1991. ISBN 0-926935-40-2. Price: $5

Text Blocks

Appropriated texts combined with notes to

create a lyrosophical text that ends with the word “yond”52 pages,

5.5″ by 8.5″. Publication Date: 24 April 1995. ISBN

0-57141-004-X. Price: $8

Text Blocks, Drawn

Abstract-expressionist

verbo-visual companion to Byrum’s Text Blocks24 pages, 5.5″ by

4.25″. Publication Date: 24 April 1995. ISBN 0-57141-010-4.

Price: $8

ARTHUR BULL

25 Scores

Zen-like meditation pieces concerned with

listening25 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 21

December 1994. ISBN 0-57141-006-6. Price: $5

JOEL CHACE

O-D-E

Images, thoughts, sentences, phrases, words

broken up, repeated with new matter in ever-slightly-varying combinations

which are scatteredly dreamed into “a floating world” that is all music,

design and lyrical connotativeness63 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″.

Publication Date: 30 December 2000. ISBN 1-57141-055-4. Price: $5

DORU CHIRODEA

Alethea Raped

Introduction by Neil S. Kvern,

Illustrations by Giulia OretttiJaunty, often satirical

surrealistic poems about things like “squeaky lobsters” and “caouchouc

wethers.”31 pages, 4.25″ by 5.5″. Publication Date: 8

December 1989. ISBN 0-926935-36-4. Price: $5

Of Metascrotum and Infradeaths

Introduction by John M. Bennett, Illustrations by Giulia

OretttiSquirming dark poems in a brilliant dark surdiction36

pages, 4.25″ by 5.5″. Publication Date: 20 December 1990. ISBN

0-926935-41-0. Price: $5

nonathambia

Rawly visceral idiolinguistic

poetry26 pages, 4.25″ by 5.5″. Publication Date: 20 June

1995. ISBN 0-57141-014-7. Price: $5

DAVE CHIROT

Anar Key Ology

Alley-raw graffiti-influenced visual

poems blowtching sunward21 pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″.

Publication Date: 24 October 1999. ISBN 1-57141-015-1. Price: $5

COBBING, GARNIER, and others

Light

One visual poem each by five poets from the US,

England, Italy, Japan and France14 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″.

Publication Date: 23 July 1994. ISBN 0-57141-002-3. Price: $5

PAUL COLLIER

Petril Wava

Microherent poems suggestive of

mistranslated troubadour songs26 pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″.

Publication Date: 2 July 1993. ISBN 0-926935-79-8. Price: $8

EDMUND CONTI

Eddies

Visual, infra-verbal and conventional light

verse33 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 17 March

1994. ISBN 0-57141-000-7. Price: $5

The Ed C. Scrolls

Light verse on the Scriptures and

related matters43 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date:

28 June 1995. ISBN 0-57141-011-2. Price: $5

JEAN-JACQUES CORY

Exhaustive Combinations

A permutation poem using just

five words over and over to say, eventually, rich things about

POSSIBILITY26 pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″. Publication Date: 12

June 1996. ISBN 1-57141-022-8. Price: $8

JWCURRY

Re:Views:Re:Sponses:

Technically wide-ranging visual

poems which review other technically wide-ranging visual poems42 pages

(including one in full color), 8.5″ by 11″. Publication Date:

16 February 1991. ISBN 0-926935-49-6. Price: $15

JWCURRY and STEVEN SMITH

Between

Illustrated by jwcurry and Bob

GrummanA poem that dislocationally follows the moon jouncingly far

beyond the conventions of June30 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″.

Publication Date: 11 March 1989. ISBN 0-926935-12-7. Price: $5

BILL DIMICHELE

Capacity X

Introduction by Laurie SchneiderA

combination of non-representational line-drawings and dislocational poems

inspired by the multifarious meanings of X38 pages, 5.5″ by

4.25″. Publication Date: 13 August 1988. ISBN 0-926935-08-9.

Price: $5

Heart on the RightAn almost incoherently

wide-ranging series of textual poems of the language-poetry school that

careen through cyanide darknesses but end “in loyalties only to the DNA of

imagination”33 pages, 8.5″ by 11″. Publication Date: 11

September 1992. ISBN 0-926935-71-2. Price: $10

JOHN DOLIS

Bl( )nk SpaceHighly literate use of parenthesis-marks

and absences (e.g., ) to poetize personally and/or intellectually-charged

life-experiences58 pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″. Publication Date:

6 December 1993. ISBN 0-926935-92-5. Price: $8

Time Flies: ButterfliesCerebral, often subtly funny

excursions through variously meaningful nullities35 pages, 5.5″ by

8.5″. Publication Date: 15 October 1999 ISBN 1-57141-049-X.

Price $8

LLOYD DUNN

Inbetweening

Introduction by F. John Herbert

A multi-paged visual poem dealing with letters and the history of the animated cartoon

56 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″.

Publication Date: 29 July 1989. ISBN 0-926935-22-4. Price: $5

CLIFF DWELLER

This Candescent World

Introduction by John Grey

Purely textual collages composed of found headlines that become highly lyrical, and readable, verse

32 pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″.

Publication Date: 21 August 1993. ISBN 0-926935-87-9.

Price: $8

JOHN ELSBERG

Broken Poems for Evita

Fissional poems

25 pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″. Publication Date: 24 August 1997.

ISBN 1-57141-041-4. Price: $8

Family Values

Wry visual and infra-verbal poems, the former generally consisting of repeated lines that form a rectangular design, the latter of subtly fragmented words

36 pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″.

Publication Date: 31 December 1996. ISBN 1-57141-029-5. Price: $8

ENDWAR

Out of Words

subtle infraverbal poetry4.5″ by 5.5″.

Publication Date: 21 December 2003.ISBN 1-57141-063-5. Price: $5

HARRY D. ESHLEMAN

The Colors in the Sky

Ortholexical verse whose subject-matter ranges from a side-show strongman to blackbirds to the art of poetry to Florida to the colors in the sky.

24 pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″.

Publication Date: 21 August 1993. ISBN 0-926935-86-0. Price: $8

GREG EVASON

NothingA series of typed/ mistyped/ overtyped/

scrawltyped visual poems counter-conscoiusing the normal mind60 pages,

8.5″ by 11″. Publication Date: 30 July 1991. ISBN

0-926935-53-4. Price: $10

3 WindowsIntroduction by Nicholas Power,

Cover by Daniel f. BradleyA collection of dislocational poems

darkening out of contemporary urban living48 pages, 5.5″ by

4.25″. Publication Date: 5 June 1988. ISBN 0-926935-04-6.

Price: $5

ARNOLD FALLEDER

The God-Shed

Introduction by Gerald BurnsLyrical poems that are exclusively verbal but so distinctively both knownstream and otherstream as to seem almost to occur in two sensory modalities at once

39 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″.

Publication Date: 26 June 1991. ISBN 0-926935-50-X. Price: $5

Midrash for Macbeth

Introduction by David Castleman, Illustrated by Gerald Burns

More by the author of The God-Shed of whom Gerald Burns wrote, “Reading Falleder is like looking for the halo of oil–the ooze– given off by sentimentality, self-indulgence–that you know is there–and not finding it. The reader is tizzied. Arnold doesn’t know (you say) what he’s doing. How could he, and break so many rules? It’s like Kit Smart at a dinner party falling on his

knees and inviting everyone to pray, or a man really proud of his daughter at her Commencement.”

59 pages, 8.5″ by 5.5″.

Publication Date: 5 July 2000. ISBN 1-57141-053-8. Price: $10

HENRY G. FISCHER

This Word

Perhaps the world’s only collection of visual

poems that rhyme54 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date:

18 November 1992. ISBN 0-926935-72-0. Price: $5

NANCY FRYE

Once Water

Quietly forceful free verse about relationships, crickets, womanhood, minnows, death . . . but above all about the divers forms of water

45 pages, 5.5″ by 8″.

Publication Date: 20 August 1992. ISBN 0-926935-61-5. Price: $8

PETER GANICK

Logical Geometries Language poems about tendons and “the

consequence of dimensions”

26 pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″.

Publication Date: 21 August 1993. ISBN 0-926935-83-6. Price: $8

SilenceMinimalist poetry contrasting numeric

sequence with chains of disconected words16 pages, 5.5″ by

8.5″. Publication Date: 1 April 1996. ISBN 1-57141-019-8.

Price: $8

PETER GANICK & SHEILA E. MURPHY

-ocracyPart of an ongoing collaboration that begins

here with Section 5: “dust/ priestesses the/ floor of/ putty-mouthed

silencers…. densest comparisons…./ your face// treasured cages/

surgically remove/ from their inhabitants/ the credo/ “trust the

process”// one relates coned by color/ team-drift….wiser than…./

openers’ fitness roles”: language-jift at its most mubile.29 pages,

5.5″ by 8.5″. Publication Date: 13 September 1997. ISBN 1-57141-050-3.

Price: $8

PIERRE GARNIER

The Words Are The World

Simple line drawings with simple

captions whose “incorrectness” jars all kinds of poetry loose–as when

“three” captions a numeral one, a numeral two, and a straight line39

pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″. Publication Date: 31 December 1996. ISBN:

1-57141-028-7. Price: $8

DAVID GIANATASIO

Bend Backward for Better ReceptionShort textual poems

with quiet but compelling addle, as in the following, which is quoted in

full: “trees, like postage stamps”30 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication

Date: 21 August 1992. ISBN 0-926935-69-0. Price: $5

LEROY GORMAN

Heavyn

Miniature fissional haiku: e.g., “fencepo st air

to snow”34 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 19 August 1992.

ISBN 0-926935-74-7. Price: $5

BOB GRUMMAN

An April Poem

A multi-paged visual poem about rain and forsythia16 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 13 April 1989. ISBN 0-926935-16-X. Price: $5

Doing Long Division in Color

special limited edition, partly hand-made;collection of mathematical poems in color.

8.5″ by 11″. Publication Date: 17 November 2001.

ISBN 1-57141-056-2. Price: $500

From Haiku To Lyriku

A participant’s Impressions of a Portion of Post-2000 North American Kernular Poetry. Acknowledged by No Academics Whatever As Worth Reading. Over Four Copies Sold in 2008 Alone.

$20 ppd (with tax included in price) 255 pages, softbound

The Runaway Spoon Press Catalogue

Of Manywhere-at-Once: Ruminations from the Site of a Poem’s Construction

(3rd, revised edition)

Part memoir, part journal of a sonnet’s construction, part discussion of poetics that begins with

the practice of Shakespeare and Keats, moves to that Yeats, Pound, Stevens and Roethke, and ends with that of contemporary visual, alphconceptual and dislocational poets such as Karl Krempton, John M. Bennett and Bob Grenier

190 pages, plus glossary and bibliography; 5.5″ by 8.5″.

Publication Date: 20 December 1998. ISBN 1-57141-045-7. Price: $15

Poemns

a re-publication of the 1966 edition of the author’s first published visual poems: two or three dozen haiku strongly influenced by E. E. Cummings

34 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″.

Publication Date: 24 August 1997. ISBN 1-57141-036-8. Price: $5

SpringPoem No. 3,719,242

A 12-page-long 6-letter one-word poem18 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″.

Publication Date: 20 December 1990. ISBN 0-926935-39-9. Price: $5

A StrayngeBook

A wacko, anti-censorship, illustrated bunny-bear book for Very Smart kids and 11 adults whose names cannot be revealed at this time. Over a hundred copies sold in less than 20 years!

38 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 6 September 1987.

ISBN 0-926935-00-3. Price: $5 ppd.

An anthology of works from the Runaway Spoon Press and a catalog at the same time, within a comic

narrative34 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 13 February 1989.

ISBN 0-926935-13-5. Price: $5

S. GUSTAV HAGGLUND

Jaguar Newsprint

Almost entirely non-representational

visual poetry sequence14 pages, 5.5″ by 8″. Publication Date: 12 June

1996. ISBN 1-57141-021-X. Price: $8

JEFFERSON HANSEN

Red Streams of George Through Pages

A visual language-poetry narrative about “george a suicide become god.”18

pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″. Publication Date: 16 July 1993. ISBN 0-926935-84-4.

Price: $8

SCOTT HELMES

Non-Additive PostulationsOne of the very few collections of mathematical poems by one author in the world24 pages,

5.5″ by 8.5″. Publication Date: 29 December 2000.

ISBN 1-57141-054-6. Price: $8

KEITH HIGGINBOTHAM

Carrying the Air on a Stick

Gnomic, usually

surrealistic, often funny “clipoems”31 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″.

Publication Date: 28 June 1995. ISBN 0-57141-017-1. Price: $5

DICK HIGGINS

Scenes Forgotten & Otherwise Remembered49 pages,

5.5″ by 8.5″. Publication Date: 28 June 1998. ISBN

1-57141–042-2. Price: $5

CRAG HILL

American Standard

Introduction by John Byrum

A collection of often-playful, always ingenious-hearted textual poems

concerned with the English language34 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″.

Publication Date: 16 April 1989. ISBN 0-926935-15-1. Price: $5

The Week

A series of sometime epigrammatic, sometimes

poetic, always reflective sentences that playground the size of a

week55 pages, 8.5″ by 11″. Publication Date: 14 February 1992. ISBN

0-926935-59-3. Price: $10

CRAG HILL and BOB GRUMMAN, editors

Vispo auf Deutsch

Verbo-visual art from 17 Austrians

and Germans58 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 26 November

1995. ISBN 0-57141-018-X. Price: $10

VIRGINIA V. HLAVSA

Festillifes

Charming visual poems about Nancy Drew and

other aspects of growing up, but also about owls, kingfishers,

sycamores–and black holes21 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date:

19 August 1992. ISBN 0-926935-73-9. Price: $5

MIMI HOLMES

A Selection of SelvesTextual Accompaniment by Jake

BerryA multi-styled series of onter-related visual

self-portraits50 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 26 June 1991.

ISBN 0-926935-51-8. Price: $5

WHARTON HOOD

House of CardsIntroduction by Marshal Hryciuk,

Illustrations by Richard BelandA collection of dislocational

haiku concerned predominantly with the pre-dawn a.m. of modern life59

pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 17 April 1989. ISBN 0-926935-18-6.

Price: $5

MARSHALL HRYCIUK

The Galloping Syntaxi StrandsDown ‘n’ dirty sequence of

various mixtures of visual poetry, textual poetry, and collages that

ranges from recondite interactions with antiquity to the

super-ephemerality of stock-market reports and magazines ads69 pages,

8.5″ by 11″. Publication Date: 10 September 1992. ISBN 0-926935-77-1.

Price: $10

G. HUTH

Ampersand Squared

an anthology of pwoermds edited by G. HUTH who also provides an absorbing introduction to the genre.

5.5″ by 4.25″. perfect-bound. Publication Date: 20 April 2004.

ISBN 1-57141-065-1. Price: $10

Ghostlight

Introduction by Bob Grumman

Haiku-vivid lyrical visual poems

36 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 20 December 1990.

ISBN 0-926935-45-3. Price: $5

WreadingsIntroduction by Crag Hill

A collection of alphaconceptual poems, or: metaphorically illuminating

Joycean neologies60 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 27

November 1987. ISBN 0-926935-02-X. Price: $5

WreadingsIntroduction by Crag HillA

second edition with new poems of a collection of infra-verbal pwoermds

such as “throught”64 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 21 April

1995. ISBN 0-57141-007-2. Price: $5

<A name=k></A>

BILL KEITH

WingdomIntroductions by Pierre Garnier and

Bob GrummanVisual poems about both actual flight and art as a

form of flight–and about all that both kinds of flight allow us to

experience22 pages. ISBN 0-926935-91-7. Price: $8

KARL KEMPTON

Fission

Introduction by Bob GrummanA collection of

one-word alphaconceptual poems, or: one-word orthographic explorations of

the language.56 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 4

January 1988. ISBN 0-926935-01-1. Price: $5

Charged Particles

Voyages into the very letters of

words to get at the heart of nature, life, and the quest to free “ego” of

its “e”41 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 21 June

1991. ISBN 0-926935-52-6. Price: $8

A Pond of Stars

Introduction by Will Inman

A collection of lyricking textual poems dealing with nature, archaeology and

ecology (and, scorchingly at times, techno-industrial anti-ecology)52

pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 24 February 1989. ISBN

0-926935-11-9. Price: $5

Portrait of Texture

A series of visual illumages

investigating the alphabet and textuality20 pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″.

Publication Date: 15 October 1999. ISBN 1-57141-047-3. Price: $8

Rose WindowA visual illumagery sequence featuring

the alphabet as a series of rose windows30 pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″.

Publication Date: 15 October 1999. ISBN 1-57141-048-1. Price: $8

The Voices of Aden

Deeply ethical reflections

transmuted to lyrical verse20 pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″.

Publication Date: 2 July 1993. ISBN 0-926935-85-2. Price: $8

Rune 6: Figures of Speech

Typoglifs semi-representationally schematizing such archetypes as the priest, the

scribe and dancers at the highest visio-lyrical level

27 pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″. Publication Date: 6 December 1993. ISBN 0-926935-89-5. Price: $8

Rune 7: Poem, a Mapping

A masterful collection of typoglific investigations of the poem as toy, as rapture, as magic, as cosmos

30 pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″. Publication Date: 6 December 1993. ISBN 0-926935-90-9. Price: $8

3 Cubed: Mathematical Poems, 1976 – 2003

One of the world’s very few books devoted entirely to mathematical and math-related

poetry by one author.

5.5″ by 8.5″. Publication Date: 3 March 2003 (03/03/03).

ISBN 1-57141-061-9. Price: $8

M. KETTNER

Full Penny Jar

Introduction by Noemie Maxwell & Nico Vassilakis

Haiku of ordinary objects wrenched into new resonances with each other

52 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. publication Date: 8 December 1989.

ISBN 0-926935-35-6. Price: $5

DAVID KOPASKA-MERKEL

Underfoot Introduction by G. Huth, Illustrations

by Sheila Kopaska-MerkelA collection of mostly ortholexical

verse whose subject matter is sometimes gothic, sometimes sci fi, but

which ranges everywhere44 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″.

Publication Date: 15 February 1992. ISBN 0-926935-60-7. Price: $5

MARTON KOPPANY

To Be Or To Be

Subtle conceptual poems like the

title-poem, which investigates various ways of considering being and

nothingness45 pages, 4.25″ by 5.5″. Publication Date: 31

December 1996. ISBN 1-57141-026-0. Price: $5

RICHARD KOSTELANETZ

Fields/Pitches/Turfs/Arenas

Introduction by Harry Polkinhorn

A collection of minimalistic but richly sense-turning visual poems

36 pages, 4.25″ by 5.5″. Publication Date: 13 February 1991.

ISBN 0-926935-48-8. Price: $5

Fulcra

pwoermds each of which breaks into two

resonatinginner words such as “dozen.”2.75″ by 4.25″.

Publication Date: 18 July 2005.ISBN 1-57141-070-8. Price: $5

MoRepartitions

Minimalist word-play poems28

pages, 4.25″ by 5.5″. Publication Date: 17 March 1994.ISBN

0-926935-97-6. Price: $5

Poetry I Shall Not Make

a highly witty list of kinds

of poems the author wouldnot make such as ones “about sexism or

nuclear war orunpopular politicians”–a definite classic4.25″ by

5.5″. Publication Date: 22 December 2003.ISBN 1-57141-064-3. Price:

$5

Repartitions IV

Single words broken into

grag/ragm/gmen/ents of fascinatingly poetic resonance20 pages, 4.25″

by 5.5″. Publication Date: 12 February 1992. ISBN

0-926935-67-4. Price: $5

JIM LEFTWICH

Khwatir

A long idiolinguistic multi-meaning prose

text43 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 28 June

1995. ISBN 0-57141-016-3. Price: $5

JONATHAN LEVANT

Five Days Shy of February

Levant, loose just shy of total linguistic irresponsibility in family matters, and breaking huge

chunks of poetry off them

30 pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″.

Publication Date: 24 August 1997. ISBN 1-57141-040-6. Price: $8

Oedipus the Anti-Aociopath (or Autumn

Angst)

Introductions by Pat Ronald, Carmen Wooster (who

is misrepresented as “Carmen Webster”), Martin Arbagi, Carol Gunther,

Judith Kitchen, Richard Rosen, Quentin R. Howard, John Horner and

James Brooks10 poems, 9 introductions24 pages, 5.5″ by

8.5″. Publication Date: 15 February 1992. ISBN 0-926935-62-3.

Price: $8

NANCY LEVANT

Generations of Sara

A short story about a daughter with poems about a love affair20 pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″.

Publication Date: 23 May 1995. ISBN 0-57141-012-0. Price: $8

DAMIAN LOPES

Transentence

Acute observations of the everyday in

slightly gnomic but accessible verse28 pages, 5.5″ by

4.25″. Publication Date: 21 December 1994. ISBN 0-57141-005-8.

Price: $5

Unclear Family

A visual poetry sequence about the

breakup of a family24 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication

Date: 15 February 1992. ISBN 0-926935-65-8. Price: $5

<A name=m></A>

CARLOS LUIS

Tell This Muchbrilliant pluraesthetic collagical

collaborations in full color with WENDY SORIN5.5″ by 8.5″. Publication

Date: 18 July 2005.ISBN 1-57141-071-6. Price: $30OUT OF

PRINT–BUT EVENTUALLY A SECOND PRINTING IS PLANNED

STEPHEN-PAUL MARTIN

ADVANCINGreceding

Introduction by Lloyd Dunn

a multi-paged visual poem dealing with the many varieties of two-dimensional

space44 pages, 4.25″ by 5.5″. Publication Date: 21 July

1989. ISBN 0-926935-21-6. Price: $8

The Flood

Introductions by Harry Polkinhorn and Richard Royal

A hilarious conflux of Noah and Reagan in visual poetry of the highest ingenuity and originality

88 pages, 8.5″ by 11″.

Publication Date: 9 September 1992. ISBN 0-926935-70-4. Price: $10

Until It Changes

Introduction by Eve Ensler

An absurdist stream-of-consciousness visual poetry narrative

which eschews grammatical progression for a kind of stacking and

unstacking48 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 12

August 1988. ISBN 0-926935-07-0. Price: $5

JOHN MARTONE

far human character

Fingerprints coalescing with hurricanes and other inter-schematizations of textual and visual imagery

that subtly map into the vagaries of the human psychology16 pages,

4.25″ by 5.5″. Publication Date: 27 June 1991. ISBN

0-926935-56-9. Price: $5

primerA collection of short haiku-like poems mostly

about eay-to-day family life58 pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″.

Publication Date: 22 December 1994. ISBN 0-57141-008-2. Price: $8

Trousseau

Introduction by Larry Eigner

Delicate but fully-charged visual poems of childhood,

Judaism and medieval times40 pages, 4.25″ by 5.5″.

Publication Date: 17 February 1991. ISBN 0-926935-46-1. Price: $5

James McGinness

The Grass PoemsIllustrated by Wes

DisneyShort lyrical poems in equal partnership with Franz Kline

Grass jutting into all sorts of human shapes47 pages, 4.25″ by

5.5″. Publication Date: 14 May 1997. ISBN 1-57141-035-X.

Price: $8

MICHAEL MELCHER

Parallel to the Shore

Meditative lyrical poems

19 pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″. Publication Date: 15 February 1992.

ISBN 0-926935-68-2. Price: $8

DAVID MILLER

Commentaries (II)

Cutting-edge visual poetry sequence specializing in over-printing and the lyrical smear.

10 pages, 11″ by 8.5″. Publication Date: 25 March 2000. ISBN 1-57141-052-X.

Price: $8

GUSTAVE MORIN

Rusted Childhood Memoirs

Visual poems accurately described by their title17 pages, 8.5″ by 11″.

Publication Date: 17 March 1994. ISBN 0-926935-96-8. Price: $10

JACK MOSKOVITZ

Artist as Autist

Introduction by Crag Hill

Arrestingly primitive black cut-outs and dislocational poems which combine in a powerful vision of psychological alienation

59 pages, 4.25″ by 5.5″. Publication Date: 16 April 1989.

ISBN 0-926935-14-3. Price: $5

Isis SlicesDisjunctional poems about the darknesses

in affairs of the heart–with collages by the author31 pages, 5.5″ by

4.25″. Publication Date: 15 February 1992. ISBN 0-926935-66-6.

Price: $5

SHEILA E. MURPHY & PETER GANICK

-ocracy Part of an ongoing collaboration that begins

here with Section 5: “dust/ priestesses the/ floor of/ putty-mouthed

silencers…. densest comparisons…./ your face// treasured cages/

surgically remove/ from their inhabitants/ the credo/ “trust the

process”// one relates coned by color/ team-drift….wiser than…./

openers’ fitness roles”: language-jift at its most mubile.29 pages,

8.5″ by 5.5″. Publication Date: 13 September 1997. ISBN 1-57141-050-3.

Price: $8

JUDY MURRAY

The Soft Sighs of IfWarm-hearted but odd-eyed lyric

poems of “lemon flies,” “marshmallow moths,” and “playing if with no

cards”24 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 22 August

1992. ISBN 0-926935-75-5. Price: $5

OBERC

DemonsRaw plaintext poems of barroom/bathroom/bedroom

and parallel rooms of the mind by one of Bukowski’s most talented

followers12 pages, 8.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 31

December 1996. ISBN 1-57141-027-9. Price: $5

CLEMENTE PADIN

Poems To Eyevisual poems, many of them chargedly

political5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 12 May 2002.ISBN

1-57141-058-9. Price: $8

MARK PETERS

Falling DownLanguage poems nonetheless achieving

poignancy without sentimentality out of experiences with slow

learners27 pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″. Publication Date: 24

August 1997. ISBN 1-57141-038-4. Price: $8

HARRY POLKINHORN

Summary Dissolution

Introduction by Dick HigginsA collage sequence combining a dislocational textual

narrative with visual imagery from music, anatomy, philately and similarly

wide-ranging and seemingly discompanionable subjects.

58 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 10 August 1988.

ISBN 0-926935-06-2. Price: $5

Teraphim

Visual poems by a leading burstnom poet/critic

60 pages, 8.5″ by 11″. Publication Date: 26 November 1995.

ISBN 0-926935-98-4. Price: $10

BERN PORTER

NeverendsIntroduction by Erika PfanderA

collage sequence whose subject is existence, from lightning through shoe

advertisements to flowers in bloom50 pages, 4.25″ by 5.5″.

Publication Date: 16 April 1988. ISBN 0-926935-03-8. Price: $5

NumbersIntroduction by Erika PfanderA

waggish collage sequence concerned with the varied ways numbers take part

in everyday life52 pages, 4.25″ by 5.5″. Publication Date:

29 July 1989. ISBN 0-926935-20-8. Price: $5

Signs

Introduction by Erika PfanderThe final

volume of Porter’s four-volume investigation of human communication46

pages, 4.25″ by 5.5″. Publication Date: 31 December 1996. ISBN

1-57141-025-2. Price: $5

SymbolsSimple-seeming but eye-opening collages by

the master42 pages, 4.25″ by 5.5″. Publication Date: 28

June 1995. ISBN 0-57141-015-5. Price: $5

BERN PORTER and MALOK

VocrascendsA satirical/lyrical high-art/crude collage

sequence by two legends of the mail art scene32 pages, 4.25″ by

5.5″. Publication Date: 12 February 1991. ISBN 0-926935-42-9.

Price: $5

BETTY RADIN

Dreamdance

Visual poetry sequence graphically and textually making knowable

secrets of the ballet. . . .15 pages, 8.5″ by 11″.

Publication Date: 13 September 1997. ISBN 1-57141-031-7. Price: $10

Hot Taters & RazzmatazzVisual poetry sequence

sputtering with colloquialisms out of Victorian England10 pages, 8.5″

by 11″. Publication Date: 13 September 1997. ISBN

1-57141-032-5. Price: $10

ARNE RAUENBERG

dislimitationVisual poetry from Germany30 pages,

5.5″ by 8.5″. Publication Date: 24 April 1995. ISBN

0-57141-009-0. Price: $8

GLENN RUSSELL

The Plantings

Introduction by Greg BoydA

collection of short, montage-illustrated surrealistic fables concerned

mainly with metamorphoses47 pages, 4.25″ by 5.5″.

Publication Date: 5 December 1989. ISBN 0-926935-34-8. Price: $5

GREGORY VINCENT ST. THOMASINO

IgneMicroherent songs of literature, philosophy and

life20 pages, 4.25″ by 5.5″. Publication Date: 24 August

1993. ISBN 0-926935-88-7. Price: $5

JACK SAUNDERS

The Husband of the Writer’s WifePlaintext poems in

tone and manner resembling Bukowski but with a plaintive belligerance

against all Literary Establishments unique to Jack–albeit with solidly

authentic and moving glimpses of his family32 pages, 5.5″ by

8.5″. Publication Date: 13 May 1997. ISBN 1-57141-040-6.

Price: $8

STACEY SOLLFREY

Turning Sights in a Circular DrivewayIntroduction by

John M. Bennett, Illustrations by Louis Steven

AllamBreeze-fresh dislocational poems concerned with the everyday

world of ice-skating, tv, laundromats. . . .32 pages, 5.5″ by

4.25″. Publication Date: 9 December 1989. ISBN 0-926935-24-0.

Price: $5

WENDY SORIN

Abzu

collages about Abzu with poems by MICHAEL

BASINSKI8.5″ by 11″. Publication Date: 3 June 2003.ISBN

1-57141-060-0. Price: $10

Tell This Much

brilliant pluraesthetic collagical

collaborations in full color with CARLOS LUIS5.5″ by 8.5″. Publication

Date: 18 July 2005.ISBN 1-57141-071-6. Price: $20

FICUS STRANGULENSIS

Transmorfations

A collection of poems each of which

consists of a word or phrase that is visually altered, step by step, until

it becomes a new word or phrase–with poetic ties to the original word or

phrase37 pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″. Publication Date: 31

December 1996. ISBN 1-57141-024-4. Price: $8

DAVID STARKEY

A Year With Gayle, And Others

A disjointed narrative

about Gayle and others in sometimes aphoristic, sometimes lyric, sometimes

who-knows-what lines, one for each day of the year27 pages, 5.5″ by

8.5″. Publication Date: 2 July 1993. ISBN 0-926935-78-X.

Price: $8

LARRY TOMOYASU

Mockingbird/Litmus

Weird but resonant (and frequently

funny) juxtapositionings of visual images and mundane but unexpected

texts32 pages, 4.25″ by 5.5″. Publication Date: 20

December 1990. ISBN 0-926935-47-X. Price: $5

ANDREW TOPEL

Pain Tings

cutting edge visual poems

5.5″ by 8.5″.

Publication Date: 19 June 2004.ISBN 1-57141-067-8. Price: $8

NICO VASSILAKIS

Artaud What

An aburdist collage sequence17 pages,

5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication Date: 17 March 1994. ISBN

0-926935-93-3. Price: $5

DornobberIntroduction by M. Kettner,

Calligraphic Illustrations by John M. Bennett,> Translations

into Greek by Helen and Mary BournasA wild short surrealistic

poem about dirt, pigeons, mothlight and . . . dornobbery33 pages, 5.5″

by 4.25″. Publication Date: 9 December 1989. ISBN

0-926935-37-2. Price: $5

Stampologue

a sequence of blocks of truncated texts

that tell several intriguingly indistinct stories simulataneously5.5″

by 4.25″. Publication Date: 17 July 2005.ISBN 1-57141-069-4. Price: $5

JOHN VIEIRA

Points on a Hazard Map

Lyric poetry at times visual,

at times infra-verbal, about “ignorance whitened” and much else.32

pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″. Publication Date: 15 October 1999. ISBN

1-57141-046-5. Price: $8

Reality Slices

A collection of textual and visual

poetry34 pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″. Publication Date: 1 April

1996. ISBN 1-57141-020-1. Price: $8

Self-Portrait with Demons

Mixture of visual and

textual poems50 pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″. Publication Date: 14

May 1997. ISBN 1-57141-033-3. Price: $8

DAN WABER

cheer

$5 ppd from The Runaway Spoon Press,

Box 495597, Port Charlotte FL 33949.

ISBN 978-1-57141-073-3<br>

Sample Poems:

excla!m

1. l

2. i

3. s

4. t

DIANE WALD

Double MirrorJump-cut poems, their lines in

alphabetical order, their subject a human relationship37 pages, 5.5″

by 8.5″. Publication Date: 9 April 1996. ISBN 1-57141-023-6.

Price: $8

PAUL WEINMAN

Photo Script

Introduction by Mike Gunderloy,

Illustrations by Walt PhillipsSatirical poems of social comment

starring the famed White Boy52 pages, 4.25″ by 5.5″.

Publication Date: 20 December 1990. ISBN 0-926935-43-7. Price: $5

IRVING WEISS

Number PoemsVisual poems and list poems about

numbers70 pages, 5.5″ by 8.5″. Publication Date: 22 August

1997. ISBN 1-57141-037-6. Price: $10

Visual VoicesVisual poetry variations on poems

written before 1900, with commentary145 pages, 8.5″ by

11″. Publication Date: 24 October 1994. ISBN 0-926935-95-X.

Price: $20

For more information regarding this title, go to <A

href=”http://www.irvingweiss.com/visual.html”>Visual

Voices</A>.

SIMON WICKHAM-SMITH

FewVisual and language poetry31 pages, 5.5″ by

8.5″. Publication Date: 17 March 1994. ISBN 0-926935-99-2.

Price: $8

TOM WILOCH

Decoded Factories of the Heart

A collection of

surrealistic haiku with collages52 pages, 4.25″ by 5.5″.

Publication Date: 23 March 1995. ISBN 0-57141-003-1. Price: $5

Neon Trance

Yet more often macabre, always

surrealistically-resonant haiku from the master of the genre30 pages,

4.25″ by 5.5″. Publication Date: 14 May 1997. ISBN

1-57141-034-1. Price: $5

Night Rain

Introduction by Robert

FrazierElegantly dislocational haiku interwoven with grandly

surrealizing collages53 pages, 5.5″ by 4.25″. Publication

Date: 26 June 1991. ISBN 0-926935-55-0. Price: $5

CHRIS WINKLER

Viscosity InductionIntroduction by Jake

BerryBawdy absurdist non-narrative collage sequence26 pages,

4.25″ by 5.5″. Publication Date: 22 February 1989. ISBN

0-926935-10-0. Price: $5

Copyright © Runaway Spoon Press 1997, 2009

.

Most people think that poetry is a genius piece of work that only the most intelligent and talented people can undertake. This is however very wrong.

Most people think that poetry is a genius piece of work that only the most intelligent and talented people can undertake. This is however very wrong.  Rhyming in poetry can sometimes become a challenging task. When trying to come up with

Rhyming in poetry can sometimes become a challenging task. When trying to come up with

Forwarded to my Facebook page. An interesting poem.