The other day at Spidertangle, Nico Vassilakis asked, “Is this acceptable as one of the many definitions of ‘vispo?’”

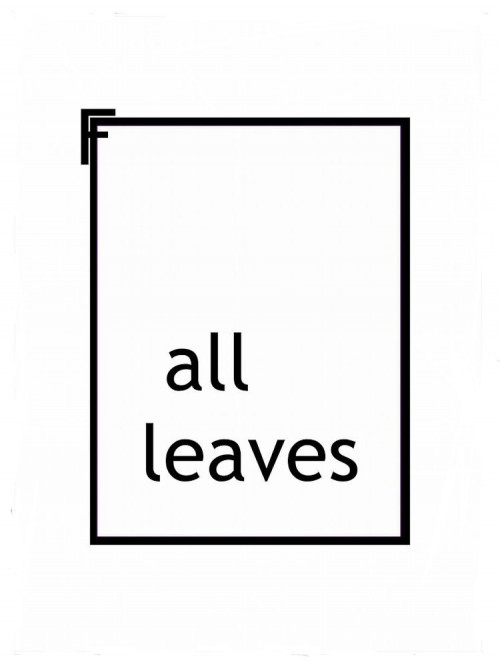

When art and text convene, the resulting blur is “vispo,” a portmanteau of “visual” and “poetry.” It’s where alphabet morphs into image and language is reinvented into visual experience.

My reply:

Seems to me we need a term meaning something like “partial loose definition.” That’s what the above seems to me—which does make it acceptable as one of many such definitions. Hyperlogical as I am, though, I believe there is only one acceptable verosophical definition of vispo (if we take it as a nickname for “visual poetry,” as I do, because is unproductively confusing to consider vispo different from visual poetry)—although I wouldn’t disagree with anyone who said we haven’t yet expressed it. Substitute “scientific” for “verosophical,” if the latter bothers you. A verosophical definition would be a rigorous definition as near complete as it is possible to be. Not an exploratory definition however useful that can be, but a final definition. Not something blurred, but something distinct one can go to the blurred from. I rather like the idea of vispo as a locus where visimagery (not “art” since music and other non-visual things are art) and language (because text alone is not language and language has always been considered necessary for poetry, and if we decide it isn’t, then what isn’t poetry) fuse (rather than merely convene) and increase the expressive potency of the other without any loss of whatever expressive potency each would have by itself.

Maybe a good distinction would be between a conversational, and a verosophical, definition of a term.

NICO: Bob, you are probably right – that distinction can be made, but I sometimes wonder if the uninitiated wouldn’t end up confused with somewhat exacting neologist definitions. I’m not inferring that what I said captures the true nature of vispo, but think simplicity, be it conversational or not, is useful. I should also say i do appreciate your work in mapping out the verbo-visual permutations that exist and the time and effort you put into it.

Thanks, Nico. I tried my best to show that what I call conversational definitions are definitely useful. Verosophical ones are, too, but probably only to verosophers—i.e., the very few seriously concerned with the search for truth.

Karl Kempton then chimed in with:

perhaps first usage or the coining of the term vispo / vizpo can add to this discussion. as far as i know, if i was not the first i was among the first in the 1970′s to use this term as a short hand in my correspondence with national and international visual poets. at that time we were freeing ourselves from the term concrete poetry to define our works. also at that time, my spelling was phonetically inclined. some have said i was texting before texting. it was an automatic follow through.

vispo / vispo was a short hand for visual poetry, the first usage of which was of european origin. “visual poetry” there, as a term, was used to free themselves from the restricted and discredited field of concrete poetry, a minimalist fission poetics blowing up language to create new patterns. this process paralleled minimalist painting and minimalist and electronic music. visual poetry was a fusion process taking these new and then newer patterns and textures wedding them with another art form or other forms.

in my opinion, demanding “recognizable” language word(s), part or parts erases, or worse censors, the possibility(ies) of wordless poetic gesture(s) and poetic aesthetic(s), rhythms, lines, pictorial metaphor(s) and countless other poetic terms that can be made visual without words. this part of the arena is border blur or the soft membrane or tissue between rigid classically drawn demarcation “scientific” lines separating classifications in the assumption each defined field is as if a dead noun and hence incapable of fluid movement or evolution.

I replied to parts of this as follows:

K: in my opinion, demanding “recognizable” language word(s),

B: As no one I know of does. I, for instance, simply ask for something called “poetry” to consist of words, as poetry always has. All this “demands” is that one not call something with no recognizable words in it “poetry.” And here we meet the bizarre belief of many that if “visual poetry” requires recognizable words, one cannot make a work of art without recognizable words. But I’m here with the good news that one can do that. One need only call what one creates something other than visual poetry!

K: part or parts erases, or worse censors, the possibility(ies) of wordless poetic gesture(s) and poetic aesthetic(s), rhythms, lines, pictorial metaphor(s) and countless other poetic terms that can be made visual without words.

B: They can be made musical without notes, too, so let’s call them vismoo.

K: this part of the arena is border blur or the soft membrane or tissue between rigid classically drawn demarcation “scientific” lines separating classifications in the assumption each defined field is as if a dead noun and hence incapable of fluid movement or evolution.

B: Right, Karl. You live in the ocean because there’s no exact way to tell where the ocean ends and land begins.

I’m afraid it comes down to an unending struggle between Snow’s two cultures.

Karl’s response:

not wanting to get into a long history as i have just been hit with a nasty cold, the long and short of it has to do in part with a generational difference as well as o so many single glance, so what concrete works and cliches, some even winding up on greeting cards. the generation difference is building upon what was done and taking it to the fusion process. there was a possibility of a real jump in multimedia but concrete in general turned off lexical poets, calligraphers, book artists, etc., a ready made audience if there ever was one. there was no embrace because the works failed to match the quality of the painters, musicians, sculptors, calligraphers, book artists, etc. not that there were exceptions such as finlay. phillips, dencker, xenakis and others made the jump to aid in the formation along with the lettrists of visual poetry.

for japan, see karl young’s intro on kitasono . having already run his run of concrete many years before concrete was coined, he did not participate in concrete be rehashing his previous concrete before concrete, but submitted his plastic poems. then the rerun story of mine and others re patchen having composed concrete before concrete then being stiff armed. others as well.

i think dencker edited the first or one of the first visual poetry anthologies, 1972. techen was published in 1978 a year before i switched kaldron from a lexical and visual poetry mix to visual poetry only. concrete works were not excluded from any of this but concrete excluded visual poets, esp the lettrists.

the ocean has no fixed line. where the chumash lived 15,000 to 20,000 years ago now under water. soon homes and cites adjacent to the ocean will receive the same fate because fools thought boundaries fixed. boundaries change. worse than building in flood plains. the wise remain on high ground. we are at 70 feet on what is an old sand dune soon to be an island. but my body will have been turned to ash by then.

out of energy,

karl

What Cathy Bennett then said, and I replied to, was:

1- “increase the expressive potency of the other without any loss of

whatever expressive potency each would have by itself. ”

Bob,

The above section*** is where you are completely wrong… and by saying

it is a “scientific” approach, still doesn’t make it right.

Can’t my (very tentative) definition be okay as a scientific one, Cathy? Do you not agree that a scientific one might have some use? In any case, I was just giving a different take on the long-difficult struggle of our language to produce a definition of vispo.

2- “because text alone is not language and language has always been

considered necessary for poetry, and if we decide it isn’t, then what

isn’t poetry”

is a problem when it comes to “asemic” vispo. “Visual Poetry” is not so self-limiting.

You lost me here. If something consisting of textual elements but no words is called visual poetry, how does that not raise the question of what is not visual poetry? Or not poetry. Or do you agree that something consisting of textual elements but not words should not be called “visual poetry?” Which, by the way, is the one thing I am far from alone in believing.

So you want to limit “text” to “language” and you also want to limit “art” to one media/ I say “NO” to both ideas.

It just seems to me that all poetry, including visual poetry (or vispo) should be limited to language, and that text is not language until it becomes words. I’ll never understand the problem so many have with this simple idea. As for “art” as both visual art and all forms of art, no one agrees with me that that can be confusing, or that it’s demeaning to visual art not to have a name of its own. It’s not at all important, though.

3- The “search for truth” is fine, except when approached in your

narcissistic manner…

Well, you have to admit that at least I don’t think we should call the search for truth “Bobgrummanism” although I have to admit that sometimes I think I’m the only one pursuing it.

you have created your mathemaku and now your definition to define it, but “in truth”-that definition*** can only be applied to your mathemaku, which you have decided to limit to your “balanced two elements”.

So, as far as your posited questions: “Is this acceptable as “one” of the many definitions”– Yes… for Bob Grumman’s mathemaku perhaps, but your mathemaku should not be held up as the highest scientific principle of “visual poetry” towards which we all must strive.

Next, Cathy’s husband, John, said, “ANY ‘definition’ of a phenomenon is necessary a definition or description of that phenom. in the past. As soon as it is made, someone comes along and does something that requires the definition be changed, in order to include it.”

But the new thing done need not be included. It may, in fact, not be a new thing: for instance, Klee and many other painters included text but not words in their paintings; their paintings are still considered paintings the subject matter of which is letters—The Villa R, for instance. No one saw, or even now sees, any need to call Klee a visual poet. The word, “chariot,” still means what it did to the Romans even though we now have the automobile. In the arts, even when definitions change, they keep some main part—e.g., the term “music” is now used for works people a hundred years ago called “noise,” but it retains its main part, which is “an art concerned with sound.” Similarly, “poetry” has come to include free verse—but hasn’t, except among certain visiotextual artists—stopped being consider an art of words. I simply don’t see why it should be. Think what mathematics would be if it were decided that numbers no longer had to be part of its definition. –Bob

In this particular case, and I believe Karl referred to this issue, is that large body of work called “visual poetry” that has NO explicitly linguistic or lettristic elements in it at all. There is a lot of work being done in this mode in Spain now. It seems to use images as concepts, or “words”; it’s a kind of picture writing. –John

If the pictures do something explicitly verbal—do more than make a gesture some consider linguistic, that is—then it would seem reasonable to call the works involved “visual poetry.” The big problem is a definition so broad or subjective as to be meaningless. Why, for instance, should ballet not be considered visual poetry? (Except metaphorically, which is completely something else.) –Bob

Joel Lipman added:

To stir & nurture, not resolve, this periodic thread, here’s Willard Bohn’s definition, suitably the opening couple sentences of his Modern Visual Poetry, Chapter 1:

“For all intents and purposes visual poetry can be defined as poetry that is meant to be seen — poetry that presupposes a viewer as well as a reader. Combining visual and verbal elements, it not only appeals to the reader’s intellect but arrests his or her gaze.”

Bohn’s second paragraph particularizes further distinctions: “Where visual poetry differs from ordinary poetry is in the extent of its iconic dimension, which is much more pronounced, and in the degree of its self-awareness. Visual poems are immediately recognizable by their refusal to adhere to a rectilinear grid and by their tendency to flout their plasticity.”

I find this definition grounding and useful, informed about the suggestions and nuances of its language. Its application enables Bohn to write a fine book on the subject, one which is pretty up-to-date, closing a chapter that discusses Perloff’s observations and compositions that explore digitalization’s “multidimensional realm of their own making.”

At some point, Bobbi Lurie and John had the following exchange:

On Tue, Dec 27, 2011 at 1:49 PM, bobbi luriewrote:

Do you consider a piece of visual art, any piece of visual art, visual poetry?

No

Or are there limitations to the definition?

Doubtless, yes. But definitions really don;t interest me very much; I never have anything I can use them for.

If I’m writing an intro to or selecting material for an anthology of something, I’ll use some kind of rule-of-thumb “definition” of what it is I’m selecting, tho it’s often pretty ad hoc, a matter of practicality or limited resources, not something I find very interesting.

Re some of what Bob & Cathy were talking about, I don;t think a “scientific” definition of art is possible or makes any sense. Science is a method, not a matter of absolute categories. A scientific study of the process of artistic creation, however, is quite possible, and could be very interesting indeed.

I couldn’t let that go by unshot at:

As an artist, I care very little about definitions; as a critic, I find them essential, and I need them to be what I consider “scientific”—i.e., objective, logical and reasonably complete (only “reasonably complete” because no definition can be absolutely complete, although the best definitions will be complete enough to satisfy any sane person).

Nico returned with:

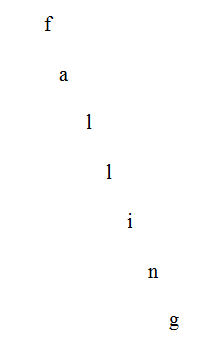

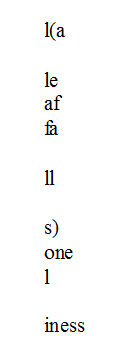

you’ll find several responses to THAT question – and others who wont care at all. i think it’s about how you define language and poetry and looking. i wonder about my recent work sometimes, if it’s even vispo anymore. ive done past work where i imbue a piece or series with a kind of rosetta stone inorder to convey how the word can transform into parts of parts of letters. even snippets of letters, thus eliminating traditional MEANING by focusing on letters alone. then my interest shifted into staring my way through a word and into a letter – and that basically annihilated MEANING, and lead to the mere visual aspect of language. is there poetry there? is there meaning there? is it elements or the ingredients of language sitting there like a recipe waiting to be cooked? i think in some sense, yes. but there are other times that i am certain it’s vispo. as language is not only words. though i do relentlessly stare at letters – is a letter a poem? this gets into bob grumman territory. he’d say no. but i think every thing looked at is, why? because our brain does nothing but process what comes across our eyes-in-the-front face. or maybe it’s 2 letters that is the ultimate denominator of poetry. as to me, a letter is an atom and a word is a molecule – and letters are constantly in search of each other to create molecules. my interest in the past few years has been to stop the letter from huddling with other letters to form a word and focus on the letter itself. is that vispo? i dont know. im sure there will be a response. but JMB is right about the spaniards – picture writing – theyre pretty stunning, but is that vispo. does it matter. like hiessenberg – the more you try pinning it down the further down the road you find it.

That stumbled me into this:

I think ultimately it will be easy to categorize these different combinations of graphics and text. Possibly even now there are brain-scanning devices that can tell what part of the brain a person most experiences a work of art. I contend (and—I believe, the certified experts in the field would agree) that so far as visiotextual art is concerned, there are two brain areas involved, the visual and the verbal. I believe conventional poetry will light up the verbal area, conventional painting and sculpture will light up the visual area, visual poetry by my definition will light up both areas about equally, and the works Nico is talking about will do weird things that we need to break the verbal area of the brain into sub-areas to talk about; I think it will mainly light up the visual area but also light up a pre-verbal part of the verbal area. I think the brain (and probably part of the nervous system prior to the brain) subject stimuli to a long sorting procedure, first identifying letters, then words, then grammatical structuring, then the connections of the words to what they denote. The sorting procedure will break down after identifying Nico’s letters BUT certainly give them an aesthetic charge that will make them different from a conventional painting—but, I believe, not enough different to make them a form of poetry, or not painting. The subject matter of lots of paintings will also activate small areas of the brain besides the visual area. Perhaps most paintings do. Needless to say, it’s all a lot more complex than this. For instance, the presence or absence of people concerns in an artwork has a huge importance.

Which is where the discussion was today t around 3 in the afternoon here in Port Charlotte, Florida.

Diary Entry

Monday, 26 December 2011, 2 P.M. About the first thing I did today was run a mile. My time was again, over eleven minutes, which is horrible. I can’t understand why I’m not getting better, although my not having run much for months, and not having run since last Friday (or was it Thursday?) may well have something to do with it. Later in the morning I gave my latest SPR column a once-over and put in into an envelope with the reviews I had on hand. That is now in my mailbox, awaiting delivery. Just now I also wrote a new Poem poem. I spent less than five minutes on it, but its central idea was one I’ve been thinking about for over a week. It’s nothing much, at all, but probably worth keeping. I used it to take care of my blog entry for today. I haven’t gotten going on what I think of as my final major chore of the year, the response to Jake’s essay. I think all I need to do is find a way to arrange what I’ve already have from what I wrote over a month ago, and several blog entries that seem relevant, and the little next matter I’ve written, and polish it, but . . . I keep waiting for the surge I used to feel whenever I was really ready to tackle a writing project, but it’s no more anywhere in me than my ability to run a bad mile instead of a horrendous mile is.

.

This entry was posted on Tuesday, December 27th, 2011 at 12:00 AM and is filed under Poetics, Terminology. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.