Today (25 October) I feel in the mood to knock out a few preliminary thoughts about Gregory Vincent St. Thomasino’s “Skips.” Eventually I’ll try to work in some of his terms. Right now, I’ll just go with first thoughts–well first attempts at analysis after having read the poem several times. I’ll re-post the poem, with my comments interrupting it.

Skips

one bus,

said of certain places

Here’s the first skip: “one bus” will not strike many readers as being something likely to be “said of certain places.” But it can make sense for places isolated so having only one bus in and out each day (or week?). In any case, an image of a bus stop entered my mind.

which may, at sites, be

or, for such as certain sites

26 October: At this point we can be sure we’re in what I call a syntax poem, which is a kind of language poem (in my poetics). A syntax poem, to put it simply, a poem whose syntax is goofy. Gregory, I’m sure, has a different name for it. “Logoclastic poem,” I think may be it. A terrific word (like so many of my neologies are, but suffering, like them, from being too idiosyncratic). Gregory would also consider his poem “cubistic,” which it can’t be, for what an artwork becomes cubistic mainly by showing a scene from two or more angles simultaneously, which words can’t do. Gregory is probably presenting his scene like Stein presented many of hers, with fractional objective and subjective (often, to my taste, too subjective) descriptions repeated many times in varied form. A kind of Jamesian hesitancy to be direct. When effective–as here, I believe–it can make a commonplace scene take on enough obscurity to allow the reader the eventual joy of solving it. Or coming close enough to doing that.

a, saying, or, for standing

a, may be holding places

I still feel like I’m at a bus stop, or maybe even in a bus station. But, helped by later sections I’ve now read more than once, I find the poem discussing language, too. One reason for that is that so many of these kinds of poems do just that. But “saying” is what language does, as well as a word (or close to a word) for “so to speak.” Using words or phrases in this double way is, of course, a primary activity of poets, but language poets tend to be more interested in doing it than other poets–enough to warp their poems’ syntax to help them do it.

At this juncture I’m taking a break until tomorrow. Hey, I could say more, but I think I’ve given you students enough to think about for this session! (Note: I can’t resist putting in another plug for the value of close readings–I find it as much fun to discover something in someone else’s poem, which I feel I’ve done here [for myself, at any rate], as it is suddenly to discover something I can use in a poem of my own that I’m working on. I really feel sorry for those who can’t appreciate close readings.)

and doubtless other combinations

one bus.

and if it is but agreeable

a hand or glove or calendar

as, he was

but not in certain places

which, when sounding

just above, and, sounding just above

are gone, or, for some time

by rote or involuntary action

between highest and lowest

is present, and absent, is gone and when

that aspect, to be events

alike, in which they are alike

between highest and lowest

the features

perceived or thought about

seem suddenly, to fit

also spelled insight or solution

the use of, or, as means his present station

and doubtless other combinations

which are themselves

his means

the skin, the hair, the coat

are fairly, then, it matches, either of the two

in which, unfit variations

are discarded

are held at mutual right angles, say

as when a new hat

or sometimes used as synonyms

is part

or,

as a rule, a new hat

is considered of involuntary action

or,

in respect to suspended judgment

in which, a measure of degree

they are, so alike

being highest, possible highest

the skin, the hair, the coat

an irrepressible action

or

due to lips

and doubtless other combinations

attained by involuntary action

as when a new hat is considered part

of one’s coat

or rival, or station

.

This entry was posted on Wednesday, October 26th, 2011 at 12:00 AM and is filed under Close Reading, Poetic Practice, Poetics. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

.

.

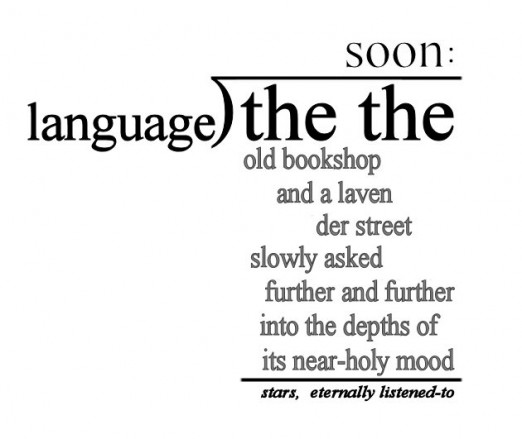

I really like this one; it strikes me as very E.E. Cummings-inspired, and I love that guy. I think the use of gray is a good idea because it gives the “remainder” more punch at the end. I’m a bit confused on reading your description in which you keep talking about Basho’s pond, which I don’t see in evidence here … I’m thinking if I had seen an earlier version of this, or I was better versed in the Grummanverse, I would understand that. And finally, you won’t have to struggle between “the” or “a” bookshop’s mood soon, where there’s just one bookshop left. Just had to end that with a little (sad) humor!

Oh, boy, I get to explain! Nothing I love more. Basho comes in because of his famousest poem, which I’ve made versions of and written about a lot, the one that has the “old pond” a frog splashes into. My poem has an “old bookshop” that has a mood with depths a street enters like (I think) the pond’s water with depths the frog enters. But now that you bring it up, I guess the allusion is pretty hermetic.

Glad you like it. I still do now that I’m looking at it again–although it strikes me as pretty weird.