I’m still in the null zone but will try to answer an important question for people starting out as visual poets who want to know how to get somewhere in the field, in whatever manner–because I often think about this, have written about it many times (albeit only semi-effectively), and was asked by someone about it recently.

First of all, I need to admit that I’ve never come close to figuring out the answer to the question brought up by most would-be poets or artists of any kind, which is, “How do I make it as a visual poet?” meaning–usually–how do I get the reputation I merit, and possibly some financial reward for my visual poetry?

(Those of you who are well-enough off–probably as a tenured English professor–to be above money concerns, and in are satisfied with the esteem of those in your literary clique–need not read further.)

My preliminary answer: I have absolutely no idea despite having been a Serious Poet (i.e., a published poet) for forty, and a Serious Visual Poet for thirty years. I have gotten a reputation as a visual poet, but only among other visual poets, and who knows how much they value my work. Even in the minute world of poetry-as-a-whole, I remain close to unknown. I’ve never gotten any kind of award for poetry, or paid more than a few dollars for a poem except for two framed, hangable poems–i.e., as a visual artist.

To continue discussing myself–because I think it the easiest way to answer the question, I began as a playwright. Not getting anywhere in that field, and always having been a sometime poet of sorts, I thought it’d be much easier to break into poetry than into playwriting, and that perhaps I could establish myself as a poet, which should heop me be taken seriously as a playwright. That’s LESSON NUMBER ONE: start at the bottom, poetry and short-story-writing seeming to me the bottom because poems and short stories are the easiest things to get published.

Among the easiest poems to get published in 1970 were haiku. I’d always liked them, and had some on hand, so tried them on a few haiku magazine publishers. LESSON NUMBER TWO is get a copy of the Dustbooks Directory of Small Presses. Look up the publishers of your kind of poetry, buy copies of their magazines, and send work to the ones whose selections you like. LESSON NUMBER THREE, is try to get into a correspondence with some of the editors of magazines you like. Starting with a fan letter, preferably a sincere one, will help. That’s something I did. As a result, one haiku editor sent me comments on my rejected haiku, including suggestions for improvement. I followed her suggestions, mostly agreeing with them, until established enough to go my own way when I thought I should.

Eventually, I found the addresses of a few publishers of concrete poetry, and started corresponding with the editor of one, sending him not poems but criticism of some poetry in his magazine. We hit it off. He asked for more essays. At length, I tried some visual poems on him. Meanwhile, he gave me the name and address of another visual poetry publisher. I got into a good correspondence with him, too, but couldn’t break into his magazine for two or three years. Both of these guys told me about others in the field, so I was soon corresponding with quite a few visual poets, many of whom also were editor/publishers. I then went to a gathering of visual poets. After that, I was an established visual poet. In the BigWorld, that meant nothing, though.

Oh, I also early on started my own press, having been able to buy a Xerox with money a grandmother had left me. I published a lot of stuff, which no doubt helped me make friends although I did it–really–because I wanted to get deserving things in print no other publisher would publish.

I still don’t understand why no visual poet has made it big, meaning gotten a reputation and access to money like Robert Haas, say. Several people have made money from visual poetry–Jenny Holzer, for one–but as visual artists not visual poets (and with mostly poor work).

Anyway, I kept internetting. One of my friends in the field had enough clout to help me get paying gigs as a critic once or twice, and into a reference book he edited; another got me into the Gale Contemporary Authors Autobiographical Essays series.

In the mid-nineties, I became active on the Internet, and got a few gigs all on my own by responding to announcements of exhibitions, anthologies, reference books needing entries.

Exhibitions. For visual poets, that is important. I’ve been in a few exhibitions, mainly because I knew the right people–fellow visual poets who were able to set up group shows. It all boils down to INTERNETTING. There are always mail art shows going on, too, that it’s worth contributing to if you’re more prolific than I. They get the name around.

Now that the Internet is here, one should use it as much as possible. Having a blog is inexpensive, and worthwhile for all kinds of reasons. A few people may go to it. The only poem of mine that ever got into a textbook (where it was mislabeled a visual poem) was seen at my blog. (I was supposed to be paid with a copy of the textbook, but the creeps never sent me a copy or replied to my queries about the matter.)

A blog can also give you writing exercise, and let you try out rough drafts.

You might also join poetry discussion groups like Spidertangle, which is primarily for visual poets. Good for internetting, for news of anthologies and shows, etc.

I’ve also tried local poetry readings and met some nice people, but haven’t furthered my career, at all. I’ve found it a waste of time trying for grants like the Guggenheim. No visual poet I know has gotten one for his poetry. John M. Bennett managed for a few years to get a grant for his magazine, Lost & Found Times. Canadians have made out pretty well with government grants, one of them getting two grants, one for himself as himself and one for himself under one of his many pseudonyms.

Of course, I’ve no doubt made things difficult for myself by being as combative as I’ve been in many of my essays, and posts to discussion groups. I don’t believe in astrology but like to say I’m a victim of Moon in Aries, which makes me that way. I’m a natural pop-off artist. I do control myself much of the time, and am also naturally able to make fun of myself, so aren’t as loathed as I might otherwise be. I actually thought that being outrageous might help me, as it has others. It hasn’t. Possibly because I’m often on everybody’s wrong side. For instance, a vocifeorous believer in the value of visual poetry, which offends conventional poets, while also a vocifeous believer that textual designage is not visual poetry, which offends most visual poets.

Note: I’m much less aware of the current scene now than I was ten years ago. I’m to the point where I’m more concerned with finishing Important Projects of mine than getting anywhere socio-economically. I rarely publish anything anywhere but here at my blog–unless solicited by a friend.

I don’t think I’ve said much but can’t right now think of anything to add. I hope what I’ve said is useful to someone. I’ll be glad to answer any questions. I’d particular like to hear from people with other ideas on how to get ahead.

Oh, and yes, it’s quite possible that one will get ahead automatically if one’s work is good enough. Mine may not be. However, I can’t accept that the entire field of visual poetry is deservedly as marginal as it’s been since ints inception–at least in the United States. In many South American countries and perhaps elsewhere, it seems to be taken much more seriously.

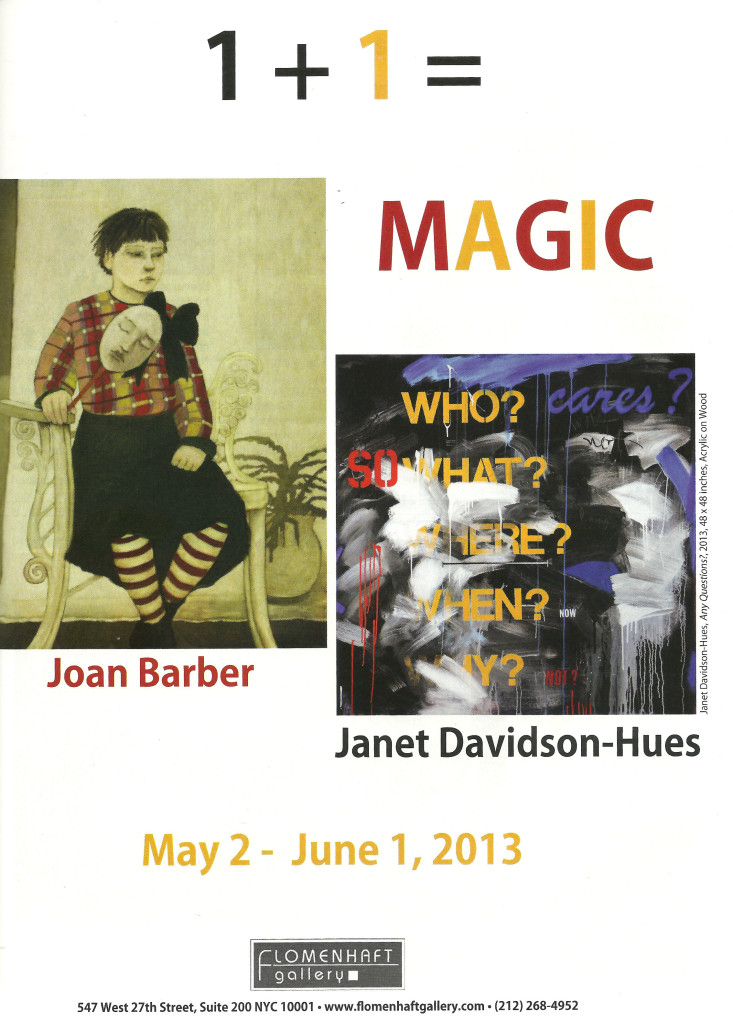

Thank you so much, Bob! I’m VERY glad you liked it and I’m grateful for your attention! The title serves only to slow the reading down in this case. It may be too overt, I’m not sure.

what id like to know is what are the 2 pieces on each side of the dash. mirror images of torn paper? or are they 2 items that give a base to the top “mountain” piece? and does the “mountain contain within it – a dash? or does the dash signify the name of the “mountain. i like it and i like what you wrote, bob. marton, youre making work that’s moving in another direction – always a good thing. i always enjoy seeing, thinking about it.

Thank you so much for your words, Nico! (I’ve just come home from vacation and read your comment.) The two pieces on the two sides of the dash are identical: they’re the image of an iceberg, taken from the internet. I’d had a certain idea, and needed an iceberg for it. But I hadn’t guessed beforehand that they would look like a pair of shoes. I’m always in a dialogue with the “material”. This time the “material” really surprised me, and it took the initiative. The second surprise came from

“Magic Wand” (of a simple image editor software). I wanted to insert a piece of mountain-like negative space (made of sky) between the two icebergs, but I did something wrong, and had to realize that the edges of the sky are “thawing” – in complete synchrony with the icebergs. (My original idea got an extra confirmation, which was stronger than mine.) I didn’t touch the image from that point on. DASH is the base of a mountain-like (and already thawing) negative space between two disappearing icebergs which are identical with each other. And the shoes belong together, and the negative space is their wearer. There’s no separate place or time for the thought “between” the two other thoughts. They “happen” at the very same moment and belong together.

Or something like that.