Entry 358 — 3 Recent Internet Posts of Mine

Three recent posts mine to take care of this entry without doing any work, two to New-Poetry, one to Geof’s blog:

1, A Response to Crisman Cooley, who wrote:

Tipping my hand. I have a criticism, not original or uncommon, that poetry today is a page phenomenon– composed on the page, published on the page, read (silently) on the page, rarely becoming sound. Poetic referents, maybe under influence of media, are primarily visual, leading sound images to clank and clatter behind. Merwin says something similar here. Though I don’t think Merwin himself embodies the solution.

If the words never stir the air, how can they emerge from anywhere in the body? I’m fine with words stirring the air, but I think the proposition that they must do that to “emerge from . . . the body” a little narrow-minded. To each his own.

I’ve been writing plays exclusively for the past 5 years and have been struck by how the play must be recomposed as soon as I hear the words out loud and see them acted out. The words need to be made physical for the physical space. And I begin to see that there is a big difference between mental words and physical words, mental writing and physical writing. If a poet does not have actors to speak the words, the next best thing is a video recording of reading the words. That is another way of making them physical. Reading them out loud to yourself doesn’t do it because the sound is conducted through bones in your head and doesn’t give an idea how the words sound to other people. So, if you don’t have access to other people reading (actors are best) you can use a device.

This is a kind of a first step toward a poetics of sound. More on that shortly.

I find my mental voice sufficient for appreciation of the verbal effects you’re speaking of. Sure, nice to hear other voices just as calligraphy is visually nice, but minor. What most counts for me is the conceptual effect of words, multiplied by metaphor, but necessarily sensual as well since metaphors depend on sensual images of some kind.

To end this lesson as unpleasantly as possible, I will now reveal what needs to be understood for an intelligent discussion of the value of sound in poetry: that there are three levels of sound possible in poetry:

1. verbal sound, or the sound all words have when pronounced

2. enhanced verbal sound, or the sound some words can have when employed melodationally–that is, in rhyme, alliteration, and the like

3. averbal sound, or the sound metaphorically interacting with words to produce sound poetry (rather than accompanying it only, as music often does)

2. A Brief Addition

I try to pause at the ends of the lines of my linguexpressive poems but when nervous can at times forget to. I think poems are generally read (but heard) much more than only heard, and that line-breaks and other kinds of flow-breaks will work on the page almost automatically. I prefer my poems to be read, if read by people intelligent enough not to speed-read them. But certainly reciting them will add something to them. The best experience of a poem would be to read it, then hear it recited while reading it. Unless you’ve got it memorized when hearing it.

3. To Geof, after he posted his latest definition of “visual poetry”: a photograph of a young man standing between the two rails of a railroad track:

Intellectual nihilism can be fun to play, I suppose, but I should think a game you can’t lose would eventually become boring.

Note: the book-title presented does not say film is visual poetry, it says film can have the effect of poetry. Ask just about anyone, even a linguist, to give a definition of poetry, and he’ll say something along the lines of “emotionally-moving words,” not “an emotionally riveting film,” or “a beautiful woman.” The fact that any word can be used metaphorically does not mean no word can be used objectively to specify something. “Cow” will always mean something that goes “moo” even though root beer with vanilla ice cream in it is called “a brown cow.” And I’ll bet “cow,” by some spelling and pronounciation or other, has <i> always</i> meant an animal going “moo” just as “poetry,” by some spelling and pronounciation or other has always meant “words doing something more special in some way than prose can.”

Addition to No. 3.:

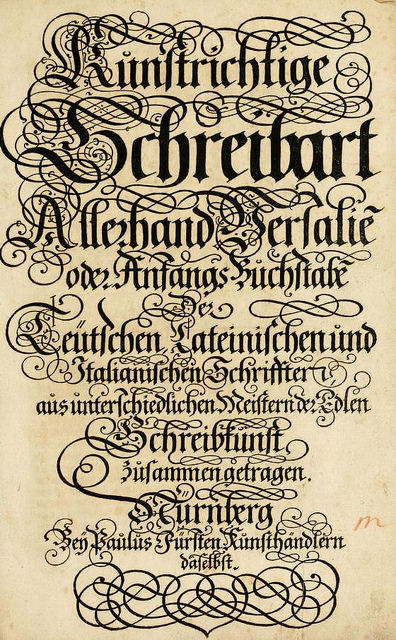

Geof gives “tone poem” as an example of a conventional use of the word, “poem,” for something that isn’t a poem to parallel his use of “visual poem” for something that isn’t a poem. The parallel is poor, however, because “tone poem” indicates something extremely specific that everyone knows is not a poem whereas “visual poem,” as Geof uses it, confusingly indicates a huge range of vastly different things, many of which are not poems, but some of which are. Moreover, it would be hard to find a good term to replace “tone poem,” but easy to replace “visual poem” where it stands for a non-poem by my “textual design,” or simply, “picture of textual matter.

if i may reproduce a post at http://mathematicalpoetry.blogspot.com/ dealing with some if these same issues as to defining a visual poem.

I would like to respond to comments by JoAnn in a round about. In 2005, I wrote Visual Poetry: A Brief History of Ancestral Roots and Modern Traditions. The title is tongue in cheek being nearly 40 pages long with a substantial number of web links and a long bibliography. I wrote it because I found few visual poets seemed to be paying attention to all the various historical and prehistorical streams and rivers flowing into the illuminated language of visual poetics. It is available at:

http://www.logolalia.com/

minimalistconcretepoetry/archives/cat_kempton_karl.html

Karl Young was among a small number of my draft readers. He and I discussed the definition of visual poetry. It was a long back and forth before agreeing upon our definition, “A visual poem may be defined simply as a poem composed or designed to be consciously seen.” This does include the gray area of written lexical poems with nontraditional line breaks such as Charles Olson’s poems and those influenced by his ground breaking essay, Projective Verse. This is lexical poetry with line breaks composed on the page as a breath score. The typewriter did change the appearance of lexical poetry on the page.

For a larger context, perhaps Karl Young’s two important essays may be of use:

NOTATION AND THE ART OF READING http://www.thing.net/~grist/ld/young/

notation/notate.htm

THE ROMAN ALPHABET

IN ITS ORIGINAL CONTEXTS

http://www.thing.net/~grist/ld/TextBackHome/Roman.htm