I had a headache when I went to bed last night that I eventually took an Advil for, which didn’t help, so at 5 A.M. I took a stronger dose of pain-medication that included the pill with an opiate in it that is my equivalent of a steroid. I believe Seth Abramson’s attack on my term, “otherstream,” contributed to my headache. I felt his argument against the term was very weak and ill-stated, but I think I’ve been somewhat stressed out for a long time–years–by my need constantly to throw my little wooden arrows at some Poetry Establishment fortress–undentingly. Now I would have to throw my arrows a goddamned gain, with almost surely no more chance of making a dent in the status quo than ever. I had to take the zoom-dose, as I call the pill with the opiate in it plus two APCs (which have caffeine, which is as important for me steroidally as the opiate) to get myself going, anyway.

Even without pharmaceutical help, I’d gotten some good ideas to use against Abramson, and/or in the larger text I hope to write about the otherstream. They include a new (guess what?) . . . coinage! My best essays as a critic almost always begin with some coinage or other of mine. This time it’s “minorstream,” and not important, at all, except that it allows me to dump “knownstream”–an excellent term that never quite fit into my system for naming the main kinds of contemporary poetry–typologically. It is now about 8 A.M. I’ll finish this entry with either my response to Abramson, or my excuse for not having finished one.

* * * I’m back nine hours later with an essay of almost 3,000 words that I consider a good rough draft

For years I’ve been arguing rather passionately for recognition of what I’ve called “otherstream poetry.” Recently, an essay by Jake Berry in The Argotist Online put me fairly central in a discussion of what I view as the opposition of the poetry establishment to otherstream poetry because of my having coined “otherstream,” and because I was one of the sixteen people who accepted an invitation to respond to what Jake wrote. For over a week the essay and the responses to it got no significant attention. Finally Seth Abramson, who was in the process of writing a series of essays that seemed to have something to do with the establishment/otherstream opposition, was drawn to defend his series against two snipes at it. One was by Jeffrey Side, who, as editor of The Argotist Online, was responsible for the publication of Jake’s essay and the discussion of it, the other by me, neither of any consequence. Abramson writes for The Huffington Review. Who knows how influential he is. All I know is that he’s posted lists of “ten best poems” that I have written contemptuously of, and short essays showing little or no knowledge of the otherstream. An establishment hack, in other words—or perhaps only a sub-establishment hack.

Which gives me an excuse to give my definition of “the Poetry Establishment.” Make that “the current American Poetry Establishment,” which I will hereafter refer to as simply, “the Establishment.” There most assuredly is one, but its members and supporters scoff at references to it because it is not a formal institution. It is also difficult to define with precision. Moreover, to speak of any powerful “establishment” paints one a probable conspiracy nut.

To start with, the Establishment consists of (1) a great many junior college, college and university English departments. I’m tempted to say it consists of all such departments, but there may be some, in junior colleges or very small colleges, that are too uninfluential to qualify as part of the Establishment. Add to this (2) all trade publications publishing poetry and/or commentary on poetry, plus all junior college, college and university presses’ staffs, again with the proviso that some may be too minor to count—those with a circulation of little over a hundred, say. One must also include (3) the few visible commentators on poetry such as Helen Vendler and Harold Bloom—those whose readership is a thousand or more. There are also (4) the members of formal establishment institutions such as the American Academy of Poets, and (5) whoever it is at significant grants- and awards-bestowing formal establishment institutions such as the Pulitzer Prize Committee; the MacArthur Foundation, the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Book Foundation, and so on, that pick the recipients of their prizes. That few or none of these groups are formally affiliated with each other is irrelevant: together they act in unison (instinctively, I believe) to favor the status quo over what I call “the Otherstream.” (I’d be surprised if I haven’t overlooked any others, so would welcome additions to my list.)

In the eighties, when I coined the term, “the Otherstream,” I only intended it to apply to poetry. Later, because I believe it covers all the arts (all the sciences, too), I replaced “poetry” with “arts,” as it is in the version I wrote for Jake’s essay, without really thinking about it. It was a bad move, because complicating the issue and because I don’t know enough about any art but poetry to be able to argue for the validity of my term’s application to it. Ergo, from now on. consider the term to apply only to contemporary American poetry.

Note well, that my term refers to kinds of poetry, not to individual poets. In other words, just because John Blank and Samantha Wicker have published collections of standard free verse that the Establishment has ignored does not make them “otherstream.” Nor does the Establishment’s brief, accidental or token recognition of a poet whose specialty is a kind of otherstream poetry such as sound poetry, make him suddenly “mainstream”—“mainstream” being those kinds of poetry recognized (more than tokenly or accidentally) by the Establishment as having value.

Defining major generalities like whatever I mean by “otherstream poetry,” is not easy. Hence, over the past twenty-five years, I’ve re-defined it many times. My attempt to get it right for Jake’s essay was the following:

‘Otherstream’ is my adjective for works of art the great majority of arts academics, well-known critics, commercial publishers and commercial magazine editors know little more than the names of, if that. A brief definition: art of a kind that’s not taught in college courses. For me, it means approximately, but only approximately, the opposite of ‘mainstream.’ What it’s the exact opposite of is ‘knownstream.’ That’s because some art is knownstream, like certain kinds of very formal verse–the sestina, say, is well known to most literature professors but is not what you’d call a kind of ‘mainstream’ poetry.”

It is this definition that Seth Abramson takes on, with the claim that “we need to point out from the outset that it’s not at all functional, for five reasons.” Three of his reasons concern terms not of hardly importance to what my definition is about. He finds genuine faults in them, but not faults that would keep anyone but a ridiculously literal-minded reader from know what I meant. He then claims my main definition is a tautology, which is preposterous, as I will show. He then has trouble with my term, “knownstream,” due to his excessive literal-mindedness. He never addresses what my term is centrally about, the difference between certified poetry and the poetry otherstream. My definition definitely had a few slight flaws, but it was still definitely functional.

I will soon get to Abramson’s objections. First, though, I would like to thank him sincerely for taking up Jake’s, Jeff’s, and my issue, and taking it up at some length (although I fear he could use an editor specializing in cutting). I may finally get my definition of the otherstream completely right, and take care of the problem I’ve always had with poetry which, in my view, is neither otherstream nor mainstream, thanks to what he wrote.

Abramson’s first reason for considering “otherstream” non-functional is that my term,

“Arts academics” (his emphasis) is not restricted to (and definitionally cannot be restricted to) English departments, so it could include a lot of people Grumman couldn’t possibly be speaking of. Yet there are also many within English departments who we wouldn’t term “arts” academics, so it doesn’t include them either. Then there are those outside “the academy” who consciously and consistently and conspicuously “academicize” discourse on and surrounding poetry (particularly avant-garde poetries) through the use of specialized terminology (often misuse, like the avant-garde’s bastardization of the term “parataxis”). Like Grumman himself. Are these folks “arts academics” also? No one knows.

I admit that my term is a muddy one, but quite innocent and of little account. (Nonetheless, it won’t be in my revised definition.) I contend that just about any of my readers will have an idea of what an arts academic is that’s reasonably close to mine. It’s basically professors and professor-types, to be no less vague—because there’s no need for great clarity in a definition the aim of which is merely to convey gists.

Next Abramson cites my “great majority” as a weasel word. Sure, it’s a weasel word, but I contend that it’s an appropriate, necessary one. I suppose I could have used “90% or more,” but it seems to me someone less ridiculously exacting than Abramson would know I meant that, or something near that. Remember, the context is a paper arguing that a great portion of the contemporary American poetry continuum has been slighted. Would “great majority” mean 51% in such a paper?

He cites “well-known” as a similar weasel word. Baloney. I’m willing to let each individual reader use his own definition of “well-known,” for I’m pretty sure he won’t use it to mean someone like me, whose blog may have a hundred readers—especially, again, in the context of an essay arguing what Jake’s argues.

Later Abramson has trouble with what I mean by “commercial publisher.” He himself answers the question with “trade press,” which is what I meant, but which “commercial publisher,” a near-synonym, got into my head first. In my improved definition I will more carefully describe which kind of publisher I mean, although I don’t think it’s possible to pin it down exactly. Again, though, almost anyone reading me would know that I mean publisher of the kinds of books that you’ll find in places like Books-a-Million.

Abramson has trouble with “knownstream,” too:

The term “knownstream,” like the term “otherstream,” depends entirely for its definition upon a term Grumman does not define–the “mainstream.” The “mainstream” is defined in a you-all-know-what-I-mean kind of way, yet that’s hardly good enough — as if we look at high-school level instruction (at least up until the mid-1990s) we’d probably say that received forms like sonnets are exactly what high school teachers teach. So when did the sonnet become non-mainstream, if it’s still the form of poetry most Americans are familiar with (I’d frankly speculate) as compared to any other? Whose mainstream are we speaking of?

I feel I don’t have to define “mainstream” in my definition of “otherstream.” If the reader has no good idea what I mean, it’s his responsibility to look it up, which he could in any standard dictionary, or he could consult other works of mine. But I do define it: it’s the approximate opposite of “otherstream.” That makes it what is taught in colleges. And I repeat that it isn’t important for the reader to know precisely what’s mainstream, otherstream or knownstream, only have a rough idea that there are three important kinds of poetry extant, and one of them is being unfairly ignored by the Establishment.

Abramson’s silliest argument against my term was calling my short definition of it a tautology:

The “brief definition” of “otherstream” art is “art that’s not taught in college courses”? Isn’t that a tautology? (Q: What’s the “otherstream”? A: Art that’s not taught in college courses. Q: How do you know it’s not taught in college courses? A: Because it’s the “otherstream,” dummy!).

This seems outright insane to me. If someone asked me what the otherstream was, and I told him it’s art that’s not taught in college courses, and he asked me how I knew it wasn’t, I would never tell him it wasn’t because it was the otherstream. After stating that I was really speaking only of poetry, which I knew something about, admitting that I really meant that less than one percent of all college courses devoted to literature had to do with otherstream poetry. I would go one to tell him I knew this because of my amazing able to infer it from: (1) the near-total absence of otherstream poetry in the books used in college classes such as the various Norton anthologies; (2) the near-total absence of otherstream poetry appearing in the books and magazines published by college and university presses; (3) the near-total absence of any mention in books about poetry written by English professors that I’d read, or read reviews of, or browsed the table of contents of; (4) my never having heard from any of the many poets I know who produce otherstream poetry that they’d been invited to read at any college; (5) my having written many times in Internet discussion groups about the Establishment’s ignorance of the otherstream without anyone’s ever denying my argument (who had the slightest idea what kind of poetry otherstream poetry is); and much else of the same sort, such as Abramson’s own long dissertation-in-progress that seems to posit a war between opposing college and university faculties as having had something of consequence to do with the state of American poetry, but says just about nothing concerning otherstream poetry, which has grown and flourished in spite of its having been ignored by both faculty-groups Abramson seems to be talking about.

My final and greatest annoyance with Abramson is with his suggestion that “quite possibly Grumman designed his terms that way (“poorly”) –and with that intention (assuring that “no one can ever quantify which poets or poetries or poems are ‘otherstream,’ so all cultural capital accruing to that term stays with Grumman”). Now it happens that I am fanatically in favor of total freedom of speech, so I would never take poor Seth to court for his allegation. I have to say, however, that statements like it are about the only verbal abuse that offends me. In this case, if Abramson had read my response to Jake’s essay, he would have seen that I state with more than reasonable clarity pretty precisely what kinds of poetry my term refers to (i.e., a list of them “would include . . . visual poetry, sound poetry, performance poetry, contragenteel poetry, mathematical poetry, infra-verbal and grammar-centered poetry (the two main schools of genuine language poetry, cruptographic poetry, cyber poetry, and others I’ve forgotten about or missed”). But even in my general definition I define what I mean with enough objectivity for anyone likely to read my writings or Abramson’s to know what poets or poetries or poems are “otherstream.” I say otherstream poetries are poetries “of a kind that are not taught in college courses.” How can anyone not know from this what I mean? Go to a few colleges and list what kinds of poetry are taught there. Compare it to a list of all the varieties of poetry currently composed in America. If you find anything on your second list that is not on your first list, it is probably otherstream. True, you would have to get samples of kinds of poetry taught from a great many colleges to be sure any particular kind of poetry was indeed otherstream.

Otherstream poets are poets who compose poetry “of a kind that are not taught in college courses”; and otherstream poems are “of a kind that are not taught in college courses.” But, as previously stated, my definition is of kinds of poetries only.

Your biggest problem (and Abramson’s) is that the Establishment will keep you ignorant of all the varieties of poetry being composed so your list of all extant kinds of poetry will be defective.

Needless to say, I should not have said otherstream poetry is what’s “not taught in college courses,” but in my hurry to knock out my definition committed the common error of all-or-nothing. I should have said otherstream poetry is what’s very rarely taught in colleges. No, what I should have said is what I’ll be saying in my final definition, “To put it in brief, it is poetry that not more than twenty of our country’s junior college, college and university literature teachers devotes any significant attention to (i.e., as much as five minutes of an entire course).” I claim that almost any reasonable reader would have understood what I wrote to mean not what I said but what I must have meant if sane—since it wouldn’t be sane to claim no college taught any kind poetry however arcane.

It is now time to unveil my Final Definition of Otherstream Poetry:

“Otherstream” is my adjective for kinds of poetries that no more than twenty or thirty members of the contemporary American Poetry Establishment, as previous defined, have any significant knowledge of. To put it in brief, it is poetry that not more than twenty of our country’s junior college, college and university literature teachers devotes any significant attention to (i.e., as much as five minutes of an entire course). To specifically list the current kinds of otherstream literature is difficult because of their lack of recognition, but my best list at the moment is visual poetry, sound poetry, performance poetry, contragenteel poetry, mathematical poetry, cyber poetry, infra-verbal and grammar-centered poetry (the two main schools of genuine language poetry), polylingual poetry almost certainly other I can’t think of at the moment or don’t know about. I might add that there are a number of varieties of some of these, particularly of visual poetry.

It is the opposite of “Mainstream,” which is mine and many others’ adjective for all the kinds of poetry sanctioned by the Establishment—in the words of Charles, Bernstein, it is our country’s “Official Verse Culture.” The mainstream, to go on, is the kind poetry that takes up 99% of the time devoted to the teaching of poetry at 99% of the junior colleges, colleges and universities in the U.S. It is the kind of poetry poetry critics more than 500 Americans have heard of write about 99.9% of the time. It is the kind of poetry 101%–ooops, I mean 99.99% of the money cultural foundations award poets. It is the kind of poetry that takes up 99.67% of the pages of every poetry anthology or poetry collection that is published in America that reaches more than 500 people.

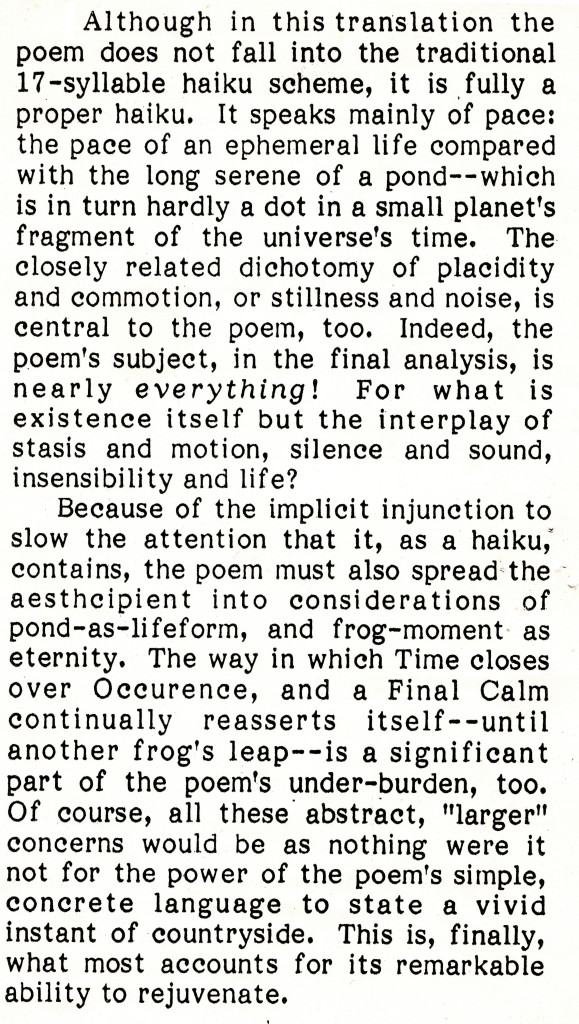

Because there are kinds of poetry well-known to, or at least somewhat known to, but pretty much ignored by members of the establishment such as the haiku, I distinguish it from both the mainstream and the otherstream as the “minorstream.” I suspect, though that more American poets compose, and more people love, minorstream poetry, which includes narrative poetry in the tradition of Robert W. Service, than mainstream poetry.

One last bit of news: Jeffrey Side is also taking on Abramson, who attacked his introduction of the Berry essay. His thrashing of Abramson is here.

.