Okay, the title is a sarcastic joke: the dialogue is only between Seth Abramson and me. My part will be Very Serious, though–as is the paragraph from a comment Seth made to my blog of a week or so ago that I’ve made his part of the following, which I sincerely hope will become just the first exchange in a multi-part series (that will become a book that will make both of us rich–okay, no more of my dumb sarcasm . . . I hope).

Seth: “Metamodernism is a tendency that’s still emerging, much like postmodernism was in the mid-1960s.”

1. as far as I’m concerned, postmodernism (considering poetry only) never emerged because it never became significantly different from the kinds of poetry being called “modernist.” The great innovator, Ashbery, just used the jump-cut poetry of “The Waste Land” more in his poetry than Eliot had.

2. “Modernism” is a moronic tag because it is based not on what the poetry it covers is and does but on when it was composed. “Postmodernism” is worse.

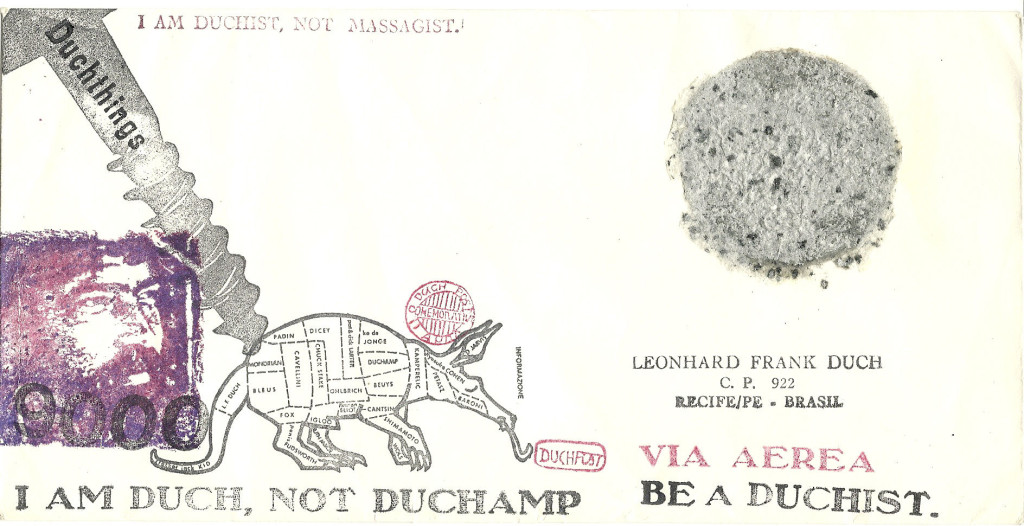

3. At around 1910-1920 a true change in the arts finished occurring. It seems to me the change was simple, no more than the acceptance of significant innovation. In poetry perhaps two specific innovations dominated. One was the broadening of allowed linguistic practice that the acceptance of free verse initiated followed by tolerance of all possible registers, and then the loosening of attachment to prose grammar beginning (seriously) with jump-cut poetry. The second was the acceptance of pluraesthetic poetry, or the significant aesthetic use of more expressive modalities than words in poetry, visual poetry being the main example of this but far the only example.

4. The chronology is of course much ore complex and difficult to unravel than the above suggests, but I’m speaking of when each new kind of poetry came into prominence, not when it was first known (which in some cases may have been centuries ago).

5. I don’t consider “otherstream poetry,” mine or others’, to be any kind of important advance on anything called modernist. I do take pride in two kinds of it that I may be the inventor of, or at least the first serious proponent of: long division poetry and cryptographic poetry. The first of these, I have to brag, has great potential for poets because of it forces those making it to be multiply metaphoric as well as makes it more open to pluraesthetic adventure than any other kind of poetry I know of. I’m prouder of the second kind because I’m more certain I invented it. Alas, I do not believe it has any future: I may myself, with just ten specimens of it, done all that can be done with it.

Seth: “If you want to understand my own (present) take on it, which of course is just proto-, for it’s entirely fluid and still developing as a concept and a poetics (it was first written of in Europe in 2010), you can read my poems on Ink Node (two poems called ‘from The Metamodernist’).” I found the following two reviews at Ink Node:

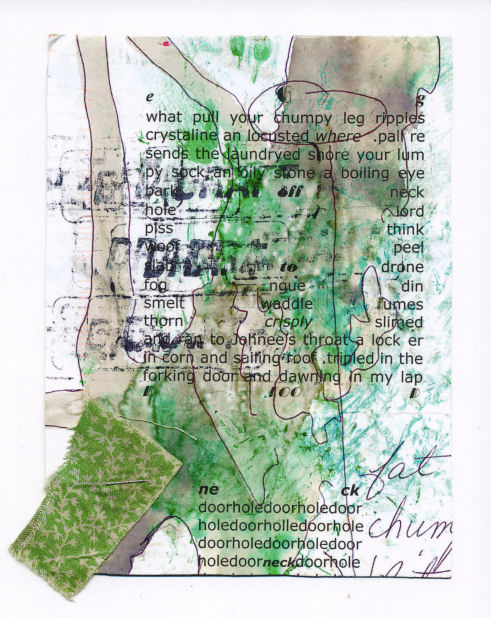

from The Metamodernist

from “A Brief Tour of the Cape”

from Section I: The Metamodernist

from “a. Against Expression”

from {KOST 99.1 Osterville. The song “We’re An American Band”}

KOST 99.1 Osterville

.

The song “We’re An American Band,” a number-one hit for Grand Funk Railroad in 1973, spawned at least seventeen contemporaneous imitations, none of which achieved the critical or commercial heights of the Railroad’s chart-topper. The Rollers, a six-piece from East Detroit, scored a minor local hit with “We’re a Guatemalan Band” just six months after Grand Funk finished its European tour in 1972. Victor Five and the Quick Six, a duo from Decatur, Georgia, penned and released “We’re Session Musicians” the same week; the song made a minor stir in Germany upon its release in 1974, and was even used to play Grand Flunk offstage during their first-ever European tour in 1975. Later that year, Ginny Decatur, a German ingénue from Athens, Georgia, scored a minor local stir with “We’re a Band,” an instrumental for oboe and drum. Not long thereafter, Frank Zappa and his Mother of Invention recorded an album of duets, We’re Only In It for the Money; the album’s title song, “We’re Between Managers,” was in 1968 a minor imitation for fresh-faced proto-punks The Rollers, whose better-known “We’re An American Band” was inspired equally by their hometown of Decatur, Georgia and a 1963 tour of Greece. Ironically, “We’re An American Band” met with decidedly less success than its immediate predecessor on the then-defunct Fontana label, “We’re a Guatemalan Band,” the latter sung by five or six session musicians from Dunkirk, Germany. The names and origins of these four musicians are unfortunately lost to time, with one exception: the lovely and talented Negro spiritualist, Virginia Georgia, best known for her lead vocals on Grand Flunk’s first album, Coast, released in January of 1999. Coast went on to win five Peabodys in September of 2001. (The cost of the LP, as of December 1998, is just over $99; it can be found for $63 here.)

Provincetown Center: The Fine Artworks

Jerry Sandusky has been performing his live act in the middle of the 600 block of Provincetown’s Main Street for six years. The act’s conceit is a simple one: Stravinsky stands naked on a street corner while painted head to toe in gold paint. The visual effect, given the artist’s meticulously-rendered 1821 “bobby” outfit, is to render Sandusky indistinguishable from a statue of a 1920s London policeman. He can often be seen in the middle of the 600 block of Provincetown’s Main Street waving his nightstick threateningly at passing children and posing playfully for photographs with healthy children. The one wrinkle in his now ten year-old routine is that he looks so convincingly statue-like that those who pose for pictures with him are wont to tell friends and relatives that photographs of Sandusky are in fact snapshots of a popular statute on the outskirts of Provincetown. It gets them every time! But then the joke is never revealed–unless, of course, it wasn’t fallen for in the first instance–meaning that for every enemy or stranger shown a photo of someone they hate or have never met standing with “Jimmy Sardoski” in Truro Center, at least ten hear the story of the famous “Jimmy Stravinsky” statue in Provincetown’s main square. And so it is that the statute has, over the last two decades, become one of Provincetown’s foremost law-themed attractions, though admittedly a difficult one to find. Jerry Sandusky Jr., who’s been performing his live act on the 600 block of Provincetown’s Curtain Street for five years, presently does a brisk trade imitating the statue in the middle of the 500 block of Provincetown’s Main Street; the requested donation per performance is five quid. You can donate to Jerry Sandusky Sr. here.

Seth: “Whether or not it’s something you admire or enjoy it is most definitely not something that’s ‘knownstream’–I have a library of over 2,000 contemporary poetry titles in my apartment right now that tell me so, inasmuch as 99.7% of them militantly exclude all metamodernistic indicia.”

Frankly, I find it hard to believe Seth considers the texts above to be poems. In fact, I think I’m missing something. Note: I vehemently oppose the belief that a poem can be anything anyone wants to call a poem. My definition is simple: a work of art in which meaningful words are centrally significant and a certain percentage of what I call “flow-breaks” (usually lineation, but anything having a comparable effect) are present. So-called “prose-poems” do not qualify. My definition is pretty conventional and probably more acceptable of poetry people than any other. My philosophy is that a definition of anything must distinguish the thing defined from everything that thing is not.

From another example of metamodern poetry I found in an Internet search, I got the impression that for Seth it’s some kind of frenetic pluraesthetic performance art. It didn’t seem to adhere to my definition of poetry though interesting-sounding. can’t say I learned enough about it to reach any even semi-valid conclusion about it, though.

Seth: P.S. The ‘psychoanalysis’ comment was re: your claim I do things to win friends–ever. That concept is foreign to me. But as you won’t believe me just saying so, look at it this way: If I’m merely ambition without courage, tell me, why do I have more enemies than you, and more powerful enemies, at that?”

I consider this outside the dialogue I’m trying to get going I want to reply to it, anyway–because I think poets are as interesting to discuss as poetry, and because I’d never thought much about my literary enemies. After thinking it over, I feel that while I have at least one hostile literary opponent, and am disliked by probably more than a handful of people, my only genuine poetry enemy is The Poetry Establishment. In short, I have fewer literary enemies than Seth, but one who is far stronger (and evil) than any of his. Evil: yes, because it has prevented me from making a living, or–actually–from making just about anything as a poet and poetry critic. The fact that it has done this unconsciously via its control of what’s published, critiqued and rewarded is irrelevant: it has done it.

As for Seth, I merely expressed the opinion that in making his list of 200 poetry people as important “advocates” of American poetry, all of them well-known members of the poetry establishment or younger people I strongly suspect (from having seen some of their work) writing and advocating nothing but the kind of poetry the establishment has certified–unless Seth can convince me that metamodern poetry is some kind of un- or anti-establishment poetry. It’s hard for me to think he’d do that unless he wanted the establishment to be his friend, but who knows?

At this point I have a question for Seth: what do you think of the idea of making a thorough list, with definitions, of all the contemporary schools of American poetry? I long ago started such a list. I asked readers to refine an add to it. Almost none did. Most who responded to it were against it. I believe because they want the public to remain ignorant of all the kinds of poetry being composed besides theirs–they want in other words, to maintain their monopoly. I on the other had think nothing could be of more value to poetry.

.

interestingly, higgins considered dadaist symbolists