Warning: What follows is almost stream-of-consciousness confusing at times as I explain, re-explain, change my mind, etc., step by step as I go. It is around 7500 words in length, too. In short, it’s almost entirely note for Me Alone. So I would advise you not to bother with it. I’m currently trying to make it coherent, and not doing so very well, but I’ll keep trying. If I succeed, I’ll post the result. I do make some interesting, perhaps even valid comments here and there. Maybe I’ll just post them under the title, “Notes on Me an’ Noam.”

But, hey, the first few paragraphs aren’t bad!

NOTES ON THE POSSIBILITY OF AN INNATE GRAMMAR

I checked my files for what I knew I’d written about linguistics so I could use some of it in this series of mine on Manywhere-at-Once and found this. I didn’t know when I’d written it, but saw a date at some point in it, 1987, so I wrote it 26 years ago. I’m posting it pretty much as is, but will soon carefully go over it, I hope. It will be interesting–to me, at any rate–to see how much I now agree with it. Oh, it makes no attempt to avoid re-inventing wheels; I find that I achieve my understandings best by doing that, rather than just memorizing the standard wheels. I then knew, and now know, just about nothing about Chomsky’s theories–I’d like to read about them, but not now, for I’m sure it would confuse me too much.

For over a year I’ve had a set of ideas as to how an innate grammar might be wired, in a simple way, into the human brain to allow for some of the effects Noam Chomsky has hypothesized. I keep forgetting important details of my system, though, so I thought I’d better get it recorded.

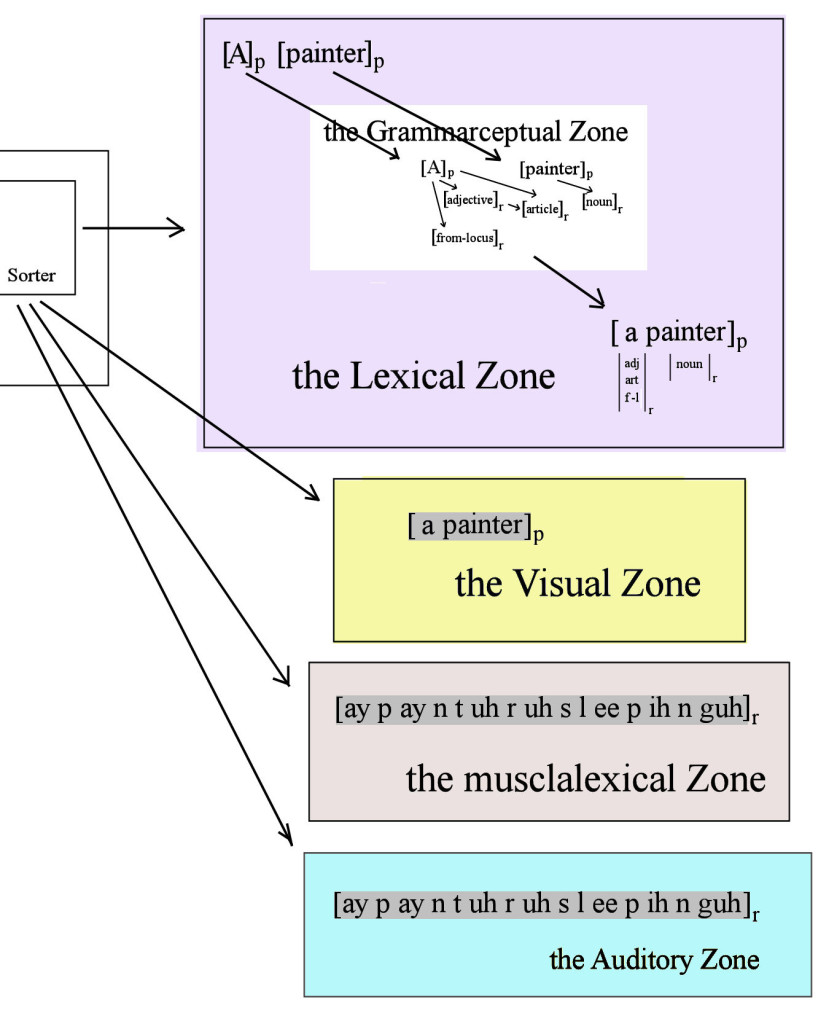

Here’s what I think: there is indeed a verbal center in the brain. It consists of two main areas, a listening center and a speech center. Hokay, I suspect that the listening center stores only those auditory data which could have been spoken by another human. This would make sense evolutionarily, I might insert: just as other specialty centers in the brain certainly evolved, it stands to reason that a center devoted only to socially consequential sounds could readily also have evolved. I am near-certain, too, that they are entered as pure phonemes–without, that is, any indicators of pitch or other qualities not semantically essential.

A phoneme, as I understand it, is the word for the smallest discrete unit of human speech: e.g., “muh,” “uh,” and “duh” when a human being hears the word, “mud.” Phonemes, I suppose I should add, are auditory and visual–the latter when turned into writing. I would be amazed if linguistics does not have a standard term for what I’m calling a visual phoneme, probably one I’ve heard. But I don’t know what it is, so will go with “visual phoneme,” until I find out.

If I’m right about the human nervous systems sensitivity to pure phonemes, then it follows that there are cells in the listening center–the main cells there, in fact–which “hear” only such phonemes. To put it more detailedly, somewhere between ear and the listening center, some mechanism collects the minute components of phonemes, reduces them to the non-varying core material (i.e., sifts out sensations of pitch and volume and the like), and passes on the results as single data each representing a different phoneme to appropriate master-cells in the cerebrum.

A similar mechanism might even collect phonemes into syllables. In any event, the listening center’s basic function is to collect pieces of words. Anyway, assuming such a center did evolve, it could account for the innate grammar we seem to possess if we assume further (for similar evolutionary reasons) that it became more specialized, dividing into smaller areas. This I feel sure in fact did happen. The result: several parts-of-speech areas. There would have been two to start with: a noun area and a verb area. The former would store nouns, the latter verbs–i.e., a cell in the former would become active when the ear heard a noun, a cell in the latter when it heard a verb. How could it know the difference? At this point I must leave standard grammatical definitions and make up (preliminary) biological definitions of parts of speech. Biologically, according to my theory, a noun is a shape, a verb a movement. The eye tells a verb from a noun, or vice versa, on the basis of which of its receptors senses it (or, more accurately, senses the stimulus responsible for it). This is not hypothetical: the eye actually does have receptors sensitive to different kinds of cues; it actually does have some receptors sensitive to

shapes (or outlines) and some sensitive to motion (or change, or there-and-not-there–on-and-off).

This variety of receptors makes sense, for sensitivity to shape is essential for recognizing parts of the environment but is not generally immediately helpful; sensitivity to motion might make the difference between being eaten or not, or catching a passing meal or not, and is thus more immediately important to any organism. Probably before any brain of complexity had arisen, certainly before the cerebrum had come about, organisms were sending data from shape receptors to shape centers, and data from motion receptors to separate motion centers to facilitate quick response. So there would have been a precedent for the existence of such separate areas in a listening center. There would have been similar selective pressures for bringing those areas about, too–even if the fact that shapes and motions weren’t already separated wasn’t responsible for their fortuitously collecting in separate areas in the listening center. A thinking organism has almost as much reason for dealing with shapes and motions separately as a reacting organism. Plans for dealing with the two items are likely to be significantly different, and it should be more efficient to be able to plan for dealing with moving things without interference from shapes (and vice versa) than it would be to deal with both together.

I should add here, though, that I believe there are also general areas in the listening center where a person could hear every kind of word coming in at once.

Regardless of evolutionary background, I believe we have a noun center and a verb center. Now, I’ve said nouns (really, words for things in the environment that we come to call nouns, but to simplify matters, let me just call them nouns–and call words for actions verbs, and so forth) are stored in the noun center, verbs in the verb center. Easy to say, but it isn’t exactly straightforward. After all, if a child sees a rolling ball for the first time and hears the word “ball,” where would he store that word? He will simultaneously perceive a shape and motion.

Indeed, this will often happen–and he will never perceive motion without shape–something has to be moving. So at first he will store “ball” in both the noun and the verb centers. Eventually, though, he will see the ball enough times when it is not moving to store it more in his noun center than in his verb center. Now, here’s a key: I believe there are in the brain receptors sensitive to whether a given center is active or not. Hence, if a child hears the word “ball” while seeing a motionless ball, he will store the word in his noun center and a receptor (or collection of receptors) will signal that the noun center is on. Its signal will be stored in a third center: a parts-of-speech center. This latter center is responsible for the innate sense of grammar all humans possess according to Chomsky, and me. Bear with me and I will at length explain how.

(Similarly, one may hypothesize that a urcept for not-verb would be activated.)

We’re not through with the child hearing the word “ball.” As I see it, the child will often store “ball” in both noun and verb centers and will thus connect it often to the concepts noun and verb; he will also often store it in the noun center alone and connect it to the concept noun alone. What will happen, then, if he hears the word “ball” when no ball is present? He will remember a round object, I’m sure (through simple association). What else? Will he remember that object at rest or rolling? And will he experience the word as a noun alone or as a noun and verb combined (or as neither)?

I theorize that he would remember the ball at rest–as a pure shape, that is–before he would remember it in motion. This because he would have more routes to the ball as shape than he would have to its motions.

I have to digress for a moment here–everything is complicated. There is more to the set-up than I have so far revealed. My listening center contains only words but there have to be places where words and sensory data connect, too–for where the actual shape of a ball links with the word for it, for example. There are such centers, and I term them “mixing” centers. There words and images co-exist and can call up each other–where “ball” can remind a child of an actual ball, and a round shape can make him think or say, “ball,” for instance. And all these centers I speak of are in contact with each other.

So the child above who hears the word “ball” will disperse energy to several areas–many many areas, in fact. He will “try to remember” in all the centers containing the datum “ball”: to wit, the noun and verb centers, and some general word center, and one or more word-and-image centers, and no doubt other areas. Also an association area where words and parts-of-speech share space will play a role.

I believe the child will activate a memory for “ball” from his noun center first because that is simply where most of the routes from “ball” will go to. In the area where images and words associate, he will remember, first, the shape of a ball. I believe words beget words faster than words beget images, though–because the word center has fewer data to compete with each other.

This is getting confusinger and confusinger. Actually he won’t remember some word–a word is the stimulus. He will remember the shape of the ball in an association area, the word&image center. The memory of the shape of the ball will in turn cause him to remember the word “ball”–as it is stored in his shape center! That is, his noun center. Why? Because the memory of ball-shape in his mind will be the result of the activation of the same cells as a perception of a ball-shape (without motion). It will thus connect into the same part of the listening center as a

ball-shape would–that is, the noun center. The child would think, “ball” as he remembered what a ball looks like; at the same time, his parts-of-speech receptors would announce “noun” and he would averbally understand that the word “ball” now in his mind was a noun.

All this could be, and probably is, assisted by other devices. For example, I suspect there are negative sensors, and sensory complexes, in the eye (and elsewhere) which are sensitive to something’s absence. One such sense might go on when there is no motion, for example. So “ball” might come to elicit memories of both motion and no-motion. If the brain is organized sensibly, and I’m sure it is, these would no doubt tend to cancel each other. Thus it would become much more likely that objects would be interpreted as nouns and not verbs. Words for shapes, in other words, would soon be come to be stored properly.

Words for motions are probably trickier since, as I’ve already said, motions can not exist without shape. So, here’s what I think: motion being more important than shape to organisms, especially primitive ones (which start, I believe it has been shown, with more visual sensitivity to motion than anything else–except darkness-versus-light), we all started with special motion centers. Shape centers came later. When they did, it would have made sense for moving stimuli to cause shape receptors to be inhibited–so the organism could concentrate ont he more crucially important motion.

ONE SEES MOTION SEPARATE FROM OBJECTS.

Later verb centers started in the listening center; when noun centers followed, verbs inhibited nouns. Because verbs are more central than nouns. To be more specific, I theorize that a word for a motion would have been stored only in the verb center–“ball” heard while the child saw a bouncing ball would thus first be stored in the verb center. The nervous system would try also to store it in the shape center as the shape it also refers to, but the receptors signalling motion would inhibit the signals of receptors for shape. Later, when the child heard “ball” while seeing a ball at rest, he would store the word in his noun center–with a sense of nounness and a sense of not-motion. Or a signal or sensation of these things. Then when he later sees the ball in motion, he would remember “ball” as both noun and verb, but his memory of it as a noun would bring with it a memory of not-motion which would tend to cancel out his memory of motion.

I’m confused again. As I have it now, any word heard in conjunction with something in motion will be stored as a verb. Any word heard in conjunction with something at rest will be stored as a noun. Verbs will quickly therefore shed any nounness–no, they’ll never be contaminated with any suspicion of nounness, for they’ll always be stored as verbs. Nouns will shed verbness, but not so quickly. As I see it, a word for an object will sometimes be stored as a verb and sometimes as a noun depending on whether its stimulus is perceived while moving or not; but when it is stored as a noun, it will store a signal against its interpretation as a verb; thus, when it is extracted from the memory for use in speech, it will tend to be extracted (or referred to) as a noun only–that is, the activation of a noun-area cell will cause the presence of a noun to be announced by the parts-or-speech center, and will inhibit that center from also announcing the presence of a verb.

There must be a simple way to put all this! Phooey.

Let me try again. An object in motion’s shape will be stored in a shape center and its motion in a motion center. A word heard while the object is perceived will be stored in a verb center, the object’s motion inhibiting any signals to the noun center. An object at rest’s shape will be stored in a shape center and a word heard while the object is perceived will be stored in a noun center, there being no motion to inhibit that. Words for motion will thus be stored in verb centers but words for objects will be stored in both noun and verb centers. Nouns, in other words, will be stored in both the noun and the verb centers. When they are used, however, both centers will be activated but the parts-of-speech receptors will signal the parts-of-speech center of the presence of a noun only, the signal for noun automatically inhibiting the signal for verb. So nouns will generally seem nouns, verbs verbs.

I say generally because, of course, verbs in everyday speech are sometimes used as nouns and vice versa. A jump occurs when one jumps, for instance; and one can “bridge” a gap. There is flexibility. So the inhibitory activity is subtle. I suppose a parts-of-speech receptor is activatated to the degree that its stimulus is large–that is, to the degree that a word is a particular part of speech; if a word is more noun than verb, it will be experienced as a noun; and if the reverse, it will be experienced as a verb. Perhaps there’s no need to hypothesize signals for nouns inhibit signals for verbs; in the everyday world, objects are generally seen more and for longer times at rest than they are in motion, so words for them in the noun center would quickly outnumber words for them in the verb center. They would therefore be experienced as nouns.

I should add one more thing here about nouns. I’ve termed them words for shapes. Actually the situation is more complex–many nouns are words for more than shapes–“fragrance,” for instance. Generalities, abstract nouns, etc. Many of these become nouns secondarily, or cerebrally–that is, they are neither nouns nor verbs because they are concerned with memeories (or concepts), not “real” things. We thus learn what part of speech they are–a complicated procedure outside the intent of this essay. But there are still words for things in the environment that neither move nor have shape–“fragrence,” as mentioned. A point: shape can be felt as well as seen. We learn other nouns–the sound of the unseen ocean might make us think of the noun “water” through simple association. More on this in due course.

There is more to verbs than I’ve so far shown. Movements often have a muscular component–movements by a person do, of course, and he is aware of it; and movements of other people and even of objects reminds him of his own movements and thus connects external movements to his muscles. So verbs possibly are words not just connected to movement but to kinesthetics, or one’s awareness of what one’s muscles are doing. This is important for another division, that of verbs into active and passive. I believe the verb center divides into other centers, including a passive center and an active center. Verbs which are experienced with a sense of muscle movement on the part of the experiencer are stored in the active verb center; those experienced with a sense of being at rest or of being acted upon rather than acting upon are stored in the passive verb center. And receptors sensitive to the two centers’ being on or off signal what kind of verb any verb is just as similar receptors signal the difference between nouns and verbs.

So we are averbally and automatically aware of two kinds of verbs. We are also aware of kinds of nouns, but before getting into that, I should discuss adjectives since they are the third main part of speech after verbs and nouns. I, as one would guess, believe that there is an adjective center in the listening center, too. I believe in a center or centers for every significant part of speech, in fact–and not only in the listening center but in the speaking center, as a matter of fact.

An object, of course, is more than shape. It is also color (or non-color), texture, odor, sound, etc. Its various qualities are also, in my view, stored in various separate centers–as well as in various association centers which combine features–color and shape, for instance. Words for qualities, like words for motion, must occur in conjunction with the perception of shapes. They are separated from verbs the same way nouns are. Their separation from nouns is trickier since all qualities are perceived with shapes and all shapes with qualities. But they shed each other. As an example, let’s consider a red ball. A child sees it several times. Sometimes he hears it called “red” and sometimes “ball.” But he also often sees a red toy truck, and a blue ball–and hears appropriate words when he sees them. So he will soon connect “red” with the color red, and “ball” with a round object. This in a general zone devoted to words and images. However, “red” and “ball” will both be stored an equal number of times in the child’s adjective (words for quality) center and noun center. How can he connect either to its part of speech?

My guess: backwards. I mean, perhaps “red” makes him remember the color red and in the process activate it in the quality center. But he wouldn’t connect it sufficiently to any noun to activate the shape center. So he could come eventually to connect the word for red more and more with not only the color red but the designation of that color as a quality! Actually, this might be the way verbs and nouns sort themselves out: each eventually comes to associate only with some specific stimulus–and be referring in the mind to that specific stimulus’s memory, it comes to be associated with what that stimulus was–i.e., shape, motion or whatever. And, now, adjective.

What’s the upshot of all this muddle? It is simple: I suggest that we learn words and automatically connect them (approximately) with their parts-of-speech. Then we learn a grammar–a general grammar. It is passed down to us by our parents or elders. It is simple: that in English sentences usually start with a noun, then have a verb–that verbs follow subjects. And adjectives precede their nouns. Because we learn a word’s part of speech as we learn the word’s meaning, we can manipulate it easily, without study. We only need learn a basic structure: subject verb predicate, for instance, and a few rules, and we can do the rest without more than learning words. And with a verb center which divides (as I will show) into tenses, we learn a verb with “ed” on it is probably past tense, so we know not only where it goes in a sentence but can form other past tenses for verbs we have just been introduced to. Etc.

CHOMSKY, CONTINUED

The Now-Knowlecule

Okay, to start again: sensations activate brain-cells; different kinds of the former activate different kinds of the latter: sensations of motion activate motion cells, sensations of shape activate shape cells, and so forth. Each kind of cells forms a separate brain center–but also contribute to more general centers, association areas and the like. But the main point here is that there are specialist centers: a motion center, a shape center, a visual quality center, and so forth. The image of a given stimulus, then, is stored in an appropriate specialist center. When it is named, the name accompanies the image in a generalist area, an area of images and words. The name at length is joined to the proper datum through a process of association explained elsewhere. From that time on, whenever it is heard or remembered, it will tend to activate a memory of the datum it names: “ball” causes, usually, a memory of a round object. When the datum is remembered, a receptor then is activated which is sensitive to its area’s activity. So the image of a ball will when remembered turn on the center it is in, the shape center, and a receptor will signal that fact. The signal in turn will come to associate with not only the image of the ball, with which it must always be associated, but with “ball,” that image’s name. It will thus link the concept “noun” to the word “ball.”

Meanwhile, “ball” will associate with too many varying motions to be likely to activate the memory of any particular motion, and therefore, secondarily, the concept “verb.” (Even if a ball only rolls, its rolling will likely be more varied than its shape, so it will always tend to associate more with its shape than its motion, and most things are at rest more than enough to readily be perceived as shapes rather than as motions.) Similarly, “ball” will associate with too many secondary qualities to activate any particular one of them and thus lead to the concept “adjective.” And “red,” for example, will associate with too many shapes (and motions) to awaken the concept “noun” (or the concept “verb”).

In the verbal center there is, I theorize, an area in which only words and parts-of-speech are stored. This would facilitate grammatical organization of one’s words.

Scores of important questions remain, of course. One concerns adverbs. I think adverbs and adjectives are both words associated with quality data. They are not separated as quality itself is from shape and motion. And, I might add, it does not seem likely that qualities are broken down into the visual, the olfactory, and so forth, although their receptors are many and varied. I suspect that would not have been efficient so that they remained combined in one group, or became combined in one group. In short, there are not significantly different kinds of quality-words. Except maybe adverbs and adjectives. These might separate through learning: adjectives always being associated with shape words, and adverbs with motion words.

Connectives (conjunctions?) and articles need to be worked into he scheme and prepositions. Equation words (is, are, etc.) Time. Possessives. But I’m too tired now.

***************** 10 January 1987 ********************************

Hokay, folks, now I have it all figured out. I don’t have time to get it all down in detail, though, so will now just put down the main points.

Verbs, I now believe, are words whose images interact with muscular activity on the part of the beholder; they are thus more than words for motions; however, they include words for motions, motions requiring muscular movement to follow–as well as being in many cases empathizable with.

Active verbs go with the sensation of active motor response, passive verbs with the sensation of resisting motor response, or motor response overcome.

Nouns are words for images (objects) which come into the brain without significant accompanying motor reactions. Ditto adjectives and adverbs.

Specialist sensors do the labelling: if a group of such sensors sees a constant shape, it signals noun; if it sees a constant quality, it signals either adjective or adverb–the first if its context is mostly nounal, the second if its context is mostly verbal.

I’m off here. I had it figured out a day or two ago, but didn’t write it down. So I’ll have to work it out still again. Meanwhile, I’d better get down what I worked out this morning.

Tense: present tense is when external input (the present) is greater than internal input (memory), and when an m-cell is activated by external impulses, it is sensed as externally activated even if impulses from internal sources equaled or were greater in strength than those external impulses. “Then” occurs when the interior activates more cells than the exterior. (Receptors there are which are sensitive to how an m-cell is activated–to which axon (or dendrite) it gets its energy.) “Then” is past and future; there is an abstract image association area where the gist of experience is remembered; it is there that “imagining” takes place–that is, events which never happened are reviewed, so to speak. Generally daydreaming, planning for the future, fantasizing, etc., take place there–one can concentrate the gist of what one wants to think about into being but not the details. Detail centers tend to go off–one’s attention narrows to “imagining,” that is. Receptors can tell whether one’s mental content is more from the imagining center or from detail centers.

When it is more from the latter, it is labelled “past.” If it is which has not happened but very likely could). When it is extremely from the former, it is labelled “fantasy” or daydreaming. At some border between the two occurs the subjunctive mood.

Edges. Data arriving to the brain with signals that edges occur in their parent images are prepostions–that is, relationships between two things, thos relationships becoming manifest at edges. Number occurs due to a “counter” in the eye (and similar counters elsewhere, perhaps). The visual counter works as follows (in my theory): Shape-detectors sensitive to the same shape signal a single center (as well as other centers). A counter at the center counts how many shape-detectors for the same shape are picking up the same shape at one time and label the shape appropriately. So the brain is aware of one, two, and more.

Connectives are probably learned–they habitually appear where verbs would be, so are taken as verbs. Subjects are objects or nouns which occur with active verbs; a nound occurring with a subject and a verb is an object. The verb is then transitive; otherwise it is intransitive. Yes, this is incomplete.

Later on 10 Jan., while lying in bed prior to going to sleep, I rethought my theory of nouns, adjectives and adverbs. I didn’t have it right above; I had it righter previously but not as right as I now think I’ve gotten it. In any event, my theory is that there are not receptors signalling what kind of perceptions are being made (or it they are, they aren’t important here); instead, there are receptors which are turned on when any m-cell in a particular specialized area has been turned on retroceptually; it will announce the identity of the area.

So far as grammar goes, three such areas are important: the changes area, the shape area, and the quality area. When something changes, as would be the case with motion visually, or the discharge of a sound or scent auditorally aor olfactorily, or the manifestation of pressure tactilely, or the like, a perception of this is stored in the changes area. Internal, or subjective changes, would be recorded here, too.

Visual shapes and shapes felt or otherwise experienced are stored in the shape area while qualities (secondary characteristics like brightness/darkness, color, pitch, smell, feel, etc.) are stored in the quality area.

Grammar receptors signal verb when a cell in the changes area becomes retroceptually active, noun when a cell in the shape area becomes retroceptually active and “quality-word” when a cell in the quality area becomes retroceptually active. Secondary grammar receptors measure the ratio of noun, verb and quality-words being experienced during a given interval and rate the overall experience verb, noun, adjective or adverb depending, respectively, on whether verbs, nouns, quality-words in combination with nouns or quality-words in combination with verbs are predominant. These secondary receptors make a final grammatical signal which joins a parts-of-speech label to the experience.

In due course a particular word loses its extraneous linkages and connects (or comes to mean) a particular part-of-speech just as it comes to mean a particular definition–e.g., just as “red” comes to mean a particular color, it comes to mean “adjective.”

A preposition is signalled when a secondary receptor senses primary receptors signaling a sequence containing sensations of one shape, then an edge, then another. Relationships in space, the way objects are orientated to each other. Sensations of location allow individual prepositions to be distinguished–“on,” for instance, is shape, downward movement to edge, then downward again to second shape. “Against” would be sideways from shape through edge to second shape. Others are more complicated and I haven’t yet worked them out. “To,” for instance, and “from.” And “for.” Maybe edges aren’t the key. Ah, the key might still be edges, in the case of “to,” “toward,” “away from,” “down to,” “up to,” and so forth, it might be changing edges that are the key. Thick edges are possible. So secondary receptors signal edge-change-of-size–thickening as something goes from something, narrowing as something approaches something.

These secondary receptors, and any associated primary receptors, are sensitive only to m-cells which are retroceptually activated, the same way other grammar sensors are.

This morning when I awoke around 5:30, I thought about my grammar theory and concluded that the imagination center not only consisted of abstractions but was easier to operate. I now believe that (1) the gist of experience, the most abstract or simplified gist of experience, is stored in such a center or centers; (2) (perhaps) greater energy is available there to make its use easier; and (3) awareness of error is reduced to facilitate uninhibited ruminating, fantasizing or the like–or, more likely, errors are not penalized to the degree they are in regular memory centers–that is, errors don’t act to lower energy or suppress erroneous passages the way they do in reality centers.

Hence, one can be much more free-roaming in the imagination area. But receptors indicate when one is in the imagination as they do when one is in past reality. They also, as I’ve hypothesized previously, indicate the ratio between what one is experiencing of the reality center compared with wxhat one is experiencing in one’s imagination and a secondary grammar receptor uses the information to signal past, future, subjunctive or daydream tense as one’s experience is decreasingly from a reality center or centers.

Actually (so my theory has it) grammar receptors cluster around master-cells primarily, not in association areas. They determine if the cell is getting activating energy from (1) sensory receptors (present tense), (2) regular memory association areas (past tense), (3) the imagination center (future tense), or ratios. But grammar receptors having to do with nouns, verbs, number, prepositions, adjectives and adverbs simply fire when the m-cell or cells they are associated with is retroceptually active; at the grammar center date from such sensors is analysed to determine finally what part of speech is appropriate.

There is a word-and-grammar association area where only words (really, phonemes or phonemes) and parts-of-speech are recorded. This facilitates a particular word’s latching onto its proper part-of-speech label and thus being used grammatically correctly.

The speech centers, incidentally, are like imagination centers in that they abstract information, or deal with data reduced to extreme simplifications. So it makes sense that speech helps with imagination and so-called higher thinking. When the imagination center is at work, memories (regular memories, I mean) also occur. In fact, memories initiate chains of imagining and vice versa. The mix is such that the mind generally “feels” the same–it feels pretty much as though it were simply remembering–unless something causes it to question its state, whereupon it will easily surmise whether it is daydreaming or thinking or remembering or whatever on the basis of what its grammar receptors are telling it about how hard its various centers are working in comparison with each other. Of course, it will always be intuitively aware of what it is doing–it will be aware of its imagination/reality ratio if not ready to verbalize that awareness.

If my idea of an imagination center is valid, it would explain Jaynes’s idea of consciousness as something which is evolved to as not truly consciousness but consciousness of having imagination, or–earlier–of having memory. But more likely of having imagination and a feeling of power over what goes through one’s mind. Also a knowledge of fantasy versus reality–the real now and the real then. Some of Jaynes’s ideas now make more sense to me: early psychotics (and present ones) might not have full (or any) use of receptors sensitive to the imagination center’s being on or off and thus would not be able to distinguish real from fantasy; or, similarly for similar reasons, past from now.

The idea of an imagination center (which I always resisted as I have always resisted any complication of my theory) gives more credence to the possibility of left-right thinking. I, however, still believe, that both sides of the brain must imagine as well as remember–but one might imagine better than the other. (Another thing I never believed.) Of course, individuals might have larger and/or more efficient imagination centers than others–men, perhaps than women, for one–especially visual imagination centers. Personality differences based on such differences would be certain.

So the actual hardware of the brain contributes to imagination as well as energy levels (in turn, of course, based on hardware, but of the endocrine system more than of the neurological system) according to my theory now. Interesting.

A thought while running on 16 September 1989 (which mayhap I already thinked afore): it may be that the way it feels behavraceptually to make a particular sound is hard-wired in our cerebrums to the way the sound sounds, and vice versa. This would be true, probably, only of phonemes–or perhaps only of phonemes and consonantal-phoneme clusters such as “str.” In any event, to hear a word would be automatically to feel oneself saying it, at least sub-vocally (i.e., in a sort of muscular outline that is short of actual audible enunciation). This means that one has a predisposition to repeat others’ words just the way one has a predisposition, anthroceptually, to repeat others’ actions. This, of course, would be a principal basis of linguistic education–and would help explain the horror ords have with deviational speech. They need to repreat it, you see, but it contradicts their previous programming (in a physical way). That, of course, leads to pain.

December 2: My dabble into language poetry got me thinking about Chomsky’s notion of an innate grammar. I’ve read a little about it, and a little here and there about linguistics, but recognize I’m no authority on it. At the same time, I believe I know more about linguistics than anyone else in the world–because I can derive everything of linguistic consequence from my knowlecular psychology.

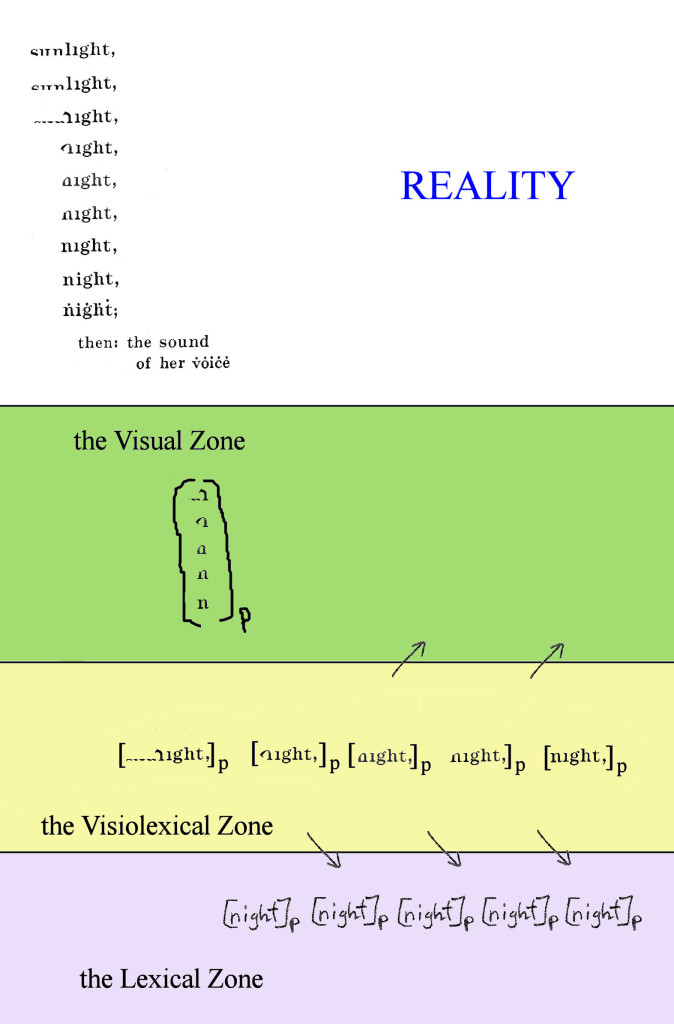

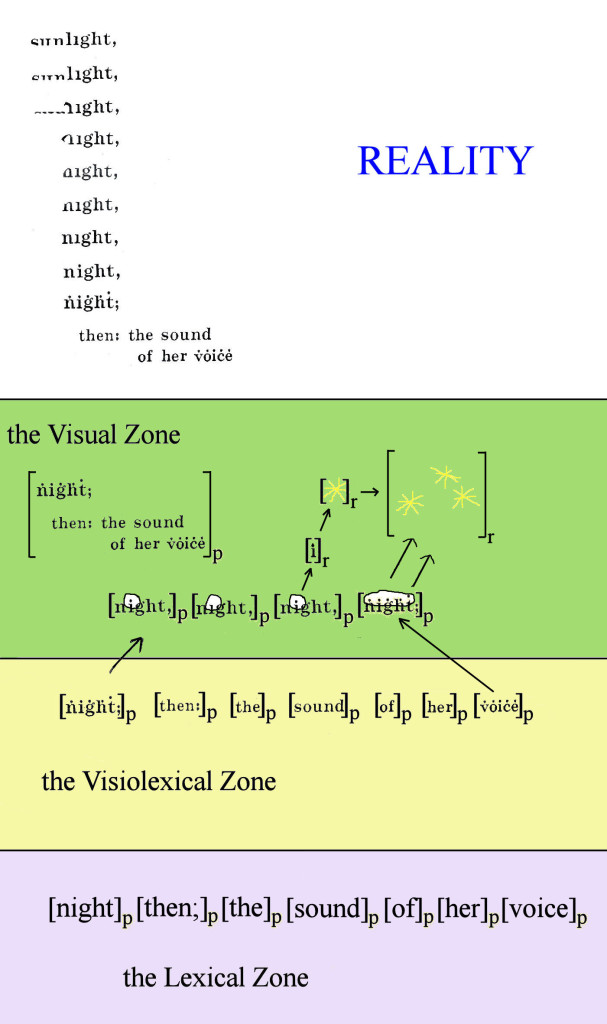

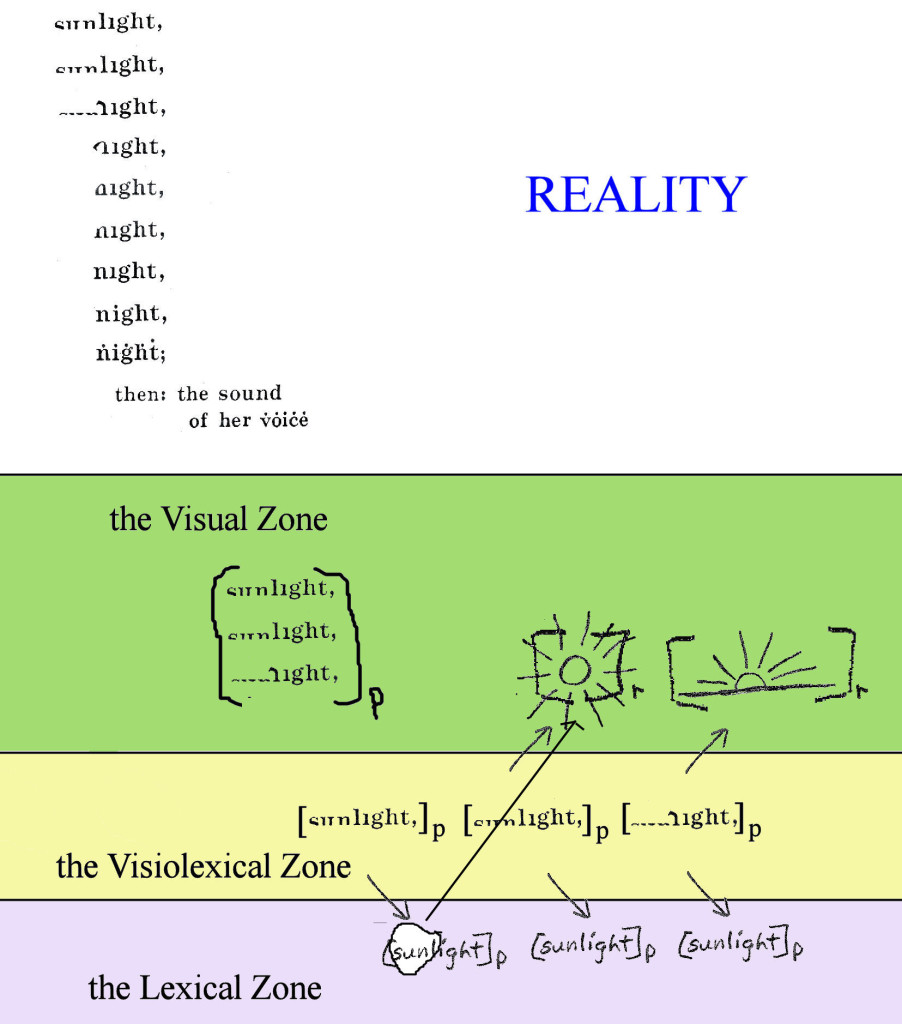

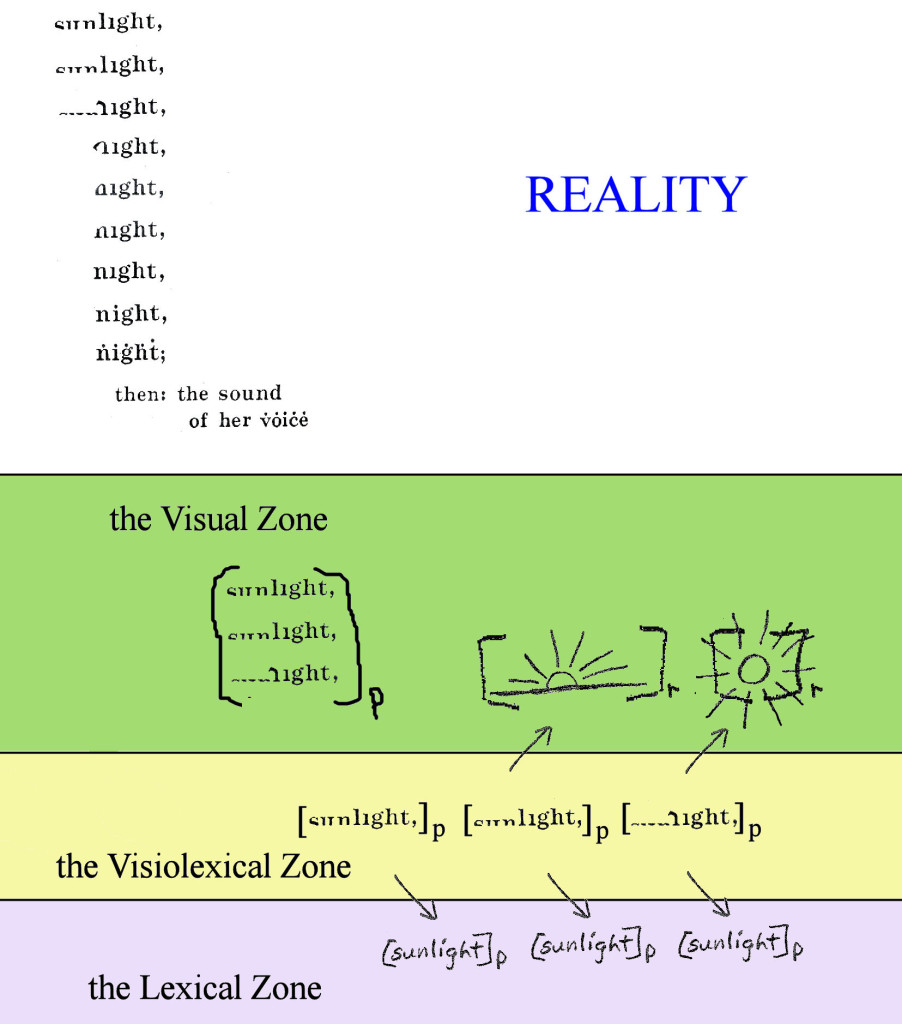

Seriously, as soon as I heard about the possibility of an innate grammar, I believed in it. So much so, that I never bothered to read anything by Chomsky, or anything by an expert in it, only a few popular magazine articles in it. I just went ahead and tried to model such a grammar as an adjunct to my model of the brain. My ideas were pretty simple. First, I posited a grammar area within the linguiceptual (or language) sub-awareness of the reducticeptual (or conceptual) awareness already part of my theory of multiple human awarenesses (and sub-awarenesses and sub-sub-awarenesses) or intelligences, or consciousnesses, or whatever. I divided the grammar area into a number of zones, one group of them having to do with parts of speech. In this group were a zone for nouns, a zone for verbs, a zone for adjectives, and so on. Also there (or so I posit at this point, at any rate) is a word zone. The noun zone’s concern would be nouns, the verb zone’s verbs, the word zone’s all words.

In other words, the human brain is innately sensitive not just to words as words, but to each word as a certain part of speech. I claim we are designed automatically to learn a vocabulary, and learn not just various words and their meanings, but various words, their meanings–and what parts of speech they are.

I hope the poetics connection is plain: language poetry, in great part, has to do with what parts of speech various words are. A large branch of it concentrates on that more than on what words mean–because a truly creative poet is compelled by his genes to explore new territory, which grammar mostly is, in poetry–not for whatever reason many language poets may give, or many of their agit-prop philistine explainers.

* * *

My simple first step toward modeling a knowlecular innate grammar was to work out ways the human nervous system might recognize parts of speech. I wrote several thousand confused words about that. This resulted in several assumptions. The first is that the nervous system recognizes shapes (some of them, like circles and rectangles, urceptually). In fact, I realized that I already had a primary awareness concerned with this, the objecticeptual awareness. I hadn’t worked out exactly what the objects it dealt with were, though. So, I now defined them a nothing more than discrete shapes, or shapes that endured in spite of being moved, or of moving, as pretty much what they visually were. Morpho-stability?

Let me revise that. The Objecticeptual Awareness is only concerned with non-living shapes; the Anthroceptual Awareness deals with living shapes. But many of the latter are objecticeptually processed because of the difficulty in telling which a shape is living or not. In any event, I claim that shape-sensors activate a certain master-cell (or perhaps a group of master-cells) in the noun-zone of the brain whenever we see a shape (or sense one via some other sense, which I will ignore here, to simplify exposition). A percept representing “noun” is the result. This percept with be stored in the noun-zone with whatever visual percepts the stimulus causing it also caused. So, a ball will caused a memory of its circular shape (and none of its “secondary qualities,” which I will discuss later) to be stored in the noun-zone with a memory of “nounness.”

I theorize that recognition of nouns was evolutionarily the first recognition life developed–after truly primitive recognitions such as bad/good. The first life-forms probably experienced the world as nothing but bad things and good things, that is.

Probably the next sensitivity evolved sensitivity to shape-alteration, particularly motion, or a shape’s change of location. I posit that we have somewhat complex senory centers which in effect photograph two successive scenes, then compare them, signalling master-cells in a verb zone whenever it detects shape-alteration. It also allows those sensors which has sensed the shape that underwent alteration to transmit to the verb-center, but not permit any other shape-sensors to do the same. Hence, the verb-zone will store only memories of shape and verbness

From the point of view of evolution (and I consider evolutionary plausibility a sine qua in the determination of the over-all plausibility of any of my hypotheses), it would make sense for an organism to isolate its awareness of the unmoving parts of its external environment from its awareness of the moving parts. It could use the first awareness to know where it was, but concentrate all its energies on the second when appropriate, such as when some motion indicates danger, or food. All of this long before the value of the separate awarenesses for communication became evident.

Sensitivity to qualities of nouns (such as the blue color of the ball previously mentioned, say) came early on, too, no doubt. I tend to think qualities were treated as objects at first, so you’d have red as a noun stored with ball as a noun in the noun-zone. It may not have led to the creation of adjective zones until speech had evolved. Ditto sensitivity to qualities of verbs. A preposition-zone would have come later, the result of sensitivity relationships. I’m confident similar reasoning could add the other kinds of words to the five so far discussed, but I’ll leave them for now as relatively unimportant, to simplify exposition.

Once life had divided reality into parts of speech, and attained speech, syntax, or the ordering of words to facilitate communication, would have followed. Because syntax seems to vary from language to language, it is probable that the syntax zone I’m sure the linguiceptual awareness possesses begins operation in a child doing little but storing “grammocepts,” or percepts indicating a part of speech, in chronological sequence. A survival of the fittest occurs with the sequences the child most hears in his particular language group coming to dominate his syntax zone. His syntax zone will then rule his vocalization zone, gradually making him use that syntax. All kinds of complications will need to be factored in, like direct objects, indirect objects, transitive and intransitive verbs, and so forth. I’ll get to the, eventually, I hope.

Well, I’ve only done a little over a thousand words rather than the fifty thousand or more I felt I had in me earlier, but I’m tired. So, I’ll leave with just a few definitions of terms important to linguistics, mostly for my own sake, though I think they’re interesting and I doubt all my readers will be familiar with all of them. I wasn’t. (Hey, none of them is a Grummanisms!) The first is “word.” It means what everyone takes it to mean, which is strange. The next is “lexeme.” For some time I’ve thought it meant word, but no, a word is a lexeme but a lexeme is not necessarily a word. For example, “kick the bucket,” is a lexeme but not a word. A lexeme, as I understand it, is one or more words acting as a word. “Kick the bucket,” which is in effect a single word, is thus a lexeme. Separately, “kicks” and “kick” are two words but only one lexeme. There may be more to lexemes than that, but nothing that should have anything to do with my theorizing, I don’t think.

A “phoneme” is very important to my theory, and to poetics. It is a unit of linguistically meaningful sound. “Kuh,” “ih,” “kuh” and “ssss” in “kicks,” for instance. Something like 44 of them, I think I read. Then there’s “morpheme,” which is some linguistic element that can be added or subtracted from a base-word, or whatever it’s called, to refine its meaning. The “extra” in “extrasensory,” for example.

I do have a neology that comes up in the discussion of visual poetry: “texteme.” This is a unit of textual communication whose purpose is to represent a sound or linguistic effect (like the pause a comma represents–as a texteme). There may well be a standard term for this; if so, I don’t know it. “Grapheme” is another word for “letter,” no more, as far as I can tell. A phonmeme in print. That sums up the terminology I’ll be using . . . I hope. It also brings me to the end of this entry.

.

Entry 1639 — Choice of Ethotactic, Part 4

Saturday, November 22nd, 2014

What I’ve said so far suggests a question to me: can something a person does with no ethical intentions be ethotactical? For instance, say I am with a friend I know to be much more poor than I and we come upon an apple tree in a public forest with one apple on it, and I pick it and eat it, not thinking of my friend. Or, for a more colorful example, say I have been taught that Irishmen are subhuman creatures without the ability to feel pain, and that hunting them will be good practice in the use of firearms that one may one day need to fight off aliens from outer space. So I shoot a few Irishmen between the eyes, inflicting pain on them without realizing it, and even perhaps killing one or two of them. Have I behaved immorally?

According to my theory of knowlecular psychology, no. That’s because an ethotactic, or the choice of a moral or immoral action, can only be the result of some anthroceptual decision based on living in harmony with a known social code.

I think I would go so far as to say that my killing an Irishmen or two in such a case is not immoral even according to most people’s standards. Many would protest, but because it would seem that I would be excusing a Nazi taught to consider Jews sub-human for gassing them. I would excuse the Nazi, but only morally. For me, he would be not immoral, but homicidally stupid—and therefore deserving to be reprimanded! Sorry. I have a weakness for black humor. What I believe is that such a person should be prevented from continuing to gas Jews by being executed—unless one truly believes some kind of re-education can make him accept Jews as human, and he is compelled to repay society for his social stupidity by spending the rest of his life shining the shoes of Jews for free or something.

Ultimately, I believe all reprehensible acts are acts of stupidity, and that what kind of stupidity is involved—moral stupidity or some other kind of stupidity—is irrelevant. Society should be maximally protected from the person acting reprehensibly (and protected from his genes, for I believe criminals [real criminals], and that’s who I’m talking about, should not be allowed to breed). Of course, I realize I’m making a complex subject seem much more cut&dry than it is. Just ideas to counteract simple-minded bad/good anti-continuumism and the insensitivity of certain sentimentalists to Evil.

About evil I will say that all definitions of it are necessarily subjective, but that it does exist, and can be defined sociobjectively. Sociobjectivity is a view of an idea that is held by such a large majority of the members of a society and which has an objective neurophysiological basis as to be close enough to true objectivity as to be taken as such. Take the evil of killing an innocent child. Almost everyone would disapprove of that, and (I believe) almost all of us are instinctively repelled by the deed, and—in fact—would instinctively try to prevent a child, innocent or not, from being killed.

Not that our instinct to use reason would necessarily not be involved. If effective, it might tell us that our standing in society will go up if we stop someone from murdering a child. Although our instinct to advance statoosnikally would be part of that. Actually, I think in most cases, protecting the child would be reflexive whereas our explanation would be taken care of mostly by our reasoning.

To be honest, if I were dominated by reason, I would never risk my life, even as the old man I now am, for some child, because what I believe I may contribute to World Culture is almost sure to be more than what the child will, however long he lives. The problem with that, of course, is that my ability to reason may be defective, in which case, my not saving a child at the risk of losing my own life would be stupid integrity–that is, acting according to my code that I should protect my own life at all costs because of its great value to the world. I claim that following that code would be absolutely valid if I were another . . . Nietzsche, without his breakdown.

Needless to say, the idea that Evil is what some deity has said it to be is absurd; various deities have universally defined certain acts as evil because the men who invented them were instinctively against those acts. Other non-universal acts, like saying something contemptuous about some deity, have also been said to have been ordained Evil by a deity invented by men not because their inventors were instinctively against such acts but because the definition of Evil helped them gain power or destroy other tribes, or simply because of some personal dislike—of a priest once clawed by a cat that made him claim his main god had defined cats as evil, for example.

I do think that reasoning should dominate every moral choice one makes, but it can’t overcome one’s instincts, all of which are ultimately moral, for a given person. We can only argue about whose individual morals would work best for the society we want to live in, and perhaps use reason to show that giving in to a society’s chosen code will be better for each individual in the long run, the long run excluding some never-seen Heaven or anything like it.

Which brings to mind the question of whether or not it is moral to lie to the masses and tell them some God will do horrible things to them if they don’t accept a society’s code. I realize that there are those who don’t believe that our species naturally, due to our genes, divides into different social classes–three of them, roughly speaking: masters, slaves, and . . . cerebreans. They’re nuts.

I divide ethics into the study of socioethotactics and the study of egoethotactics . . . I think. There are two major problems: formulation of a maximally fair and biologically advantageous set of socioethotactics by a society, and an individuals’ reconciling his inevitably conflicting set of egoethotactics with his society’s socioethotactics.

More on this eventually, if I think I can say anything at all interesting about it.

* * *

Note: on the day I made my first entry here about ethotactics, 36 people checked up on me at my Wikipedia entry; rarely do more than 4 people visit it on a day, and none since the first month it was up have anywhere near that many done so. Were they fans of Jonah Goldberg, whose article I was commenting on? The visits after that have been few, for or five in a day at most.

Last, and definitely least, here’s this SURVEY again:

Please, Dear Reader, I implore thee: when you have read as much of this entry as you feel like reading, let me know whether you have found it worth reading in full or not by clicking “YES” or “NO” below. You would help me a great deal, and might even get me to make my entries more reader-friendly. (And for the love of Jayzuz, please don’t try to spare my feelings by politely declining to click the NO although you think the entry Vile Beyond Imagination. Oh, some of you may need to know that I am not asking you whether you agree with me or not!)

YES

NO

Note: I will be repeating this request in some of my entries to come. Feel free to click one of my buttons each time I do, but please don’t click either more than once a day.

.

Posted in Ethics, Grumman coinage, Jonah Goldberg, Political Commentators | No Comments »