Recently, I’ve been going through the files with the graphics but not the texts of entries I made to my previous blog in search of mathemaku of mine. I want to number them all, so need a complete list of them. I think I posted just about all of them to my blog. In any event, yesterday I brought up a file for an entry (Blog959) whose visits was recorded as close to 200. Rarely did my old entries get more than 20 visits. Curious to see what was in the blog, I then brought up the file that had its text, which I think worth quoting here:

17 September 2006: Among the many intriguing items at Crag Hill’s Poetry Scorecard is this found poem of Crag’s that he posted 3 September:

From Index of First Lines Selected Poems Charles Olson

. I come back to the geography of it,

. I don’t mean, just like that, to put down

. I have been an ability–a machine–up to

. I have had to learn the simplest things

. I live underneath

. I looked up and saw

. Imbued / with the light

. I met Death–he was a sportsman–on Cole’s

. In cold hell, in thicket, how

. In English the poetics became meubles–furniture–

. is a monstrance,

. I sing the tree is a heron

. I sit here on a Sunday

. It’s so beautiful, life, goddamn death

. it was the west wind caught her up, as

Amazing poem, this. I’m not a big fan of Olson’s, though I believe he is a major poet, and that some of his poems are A-1. Surely, these lines could only have been from a poet, though. I recognize one or two, but in this discussion will not look up any of them. (Oops, I realize I couldn’t look up very many of them; I do have The Maximus Poems, and several of my anthologies have poems by Olson, but I don’t have the Selected Poems.)

“I come back to the geography of it,”

Anyway, what a beginning, this return to some geography. Olson was probably only returning to a genuine geography, of the locale I feel he jabbered too much about, but here–dislocated by the line-break–”geography” can wing us to the terrain of all kinds of things, including the memory of a breakfast, banking procedures, 3 A.M., everything having a geography. Less surlogically, the word brings us to fundamentals, to the earth, to reality seen large, solid, inanimate . . .

What, I suddenly wonder, would the geography of geography be? Poems like this– effective jump-cut poems, that is–can flip us into such questions. Questions that resonate for the person flipped into them, I mean–as this one will surely not for everyone.

“I don’t mean, just like that, to put down”

Now a jump-cut leaving “geography” to simmer unconnected to any specific, and making the poem’s narrator more than a pronoun through his attempt to explain himself better. His explanation is broken off before getting anywhere, which effectually explains all the better his state of being at loose ends. A main interest is in whether he has just dropped one activity to return to the geography of whatever he’s involved in, and/or inadvertantly “put down” whatever he was doing because superficial or the like compared to geographical questions. “I have been an ability–a machine–up to”

The narrator continues trying to explain himself without finishing any of his ventures into self-analysis. I take this line to mean he’s not been personally/emotionally involved in whatever it is he’s talking about, “up to (now).” Note, by the way, how this line, with its pronounced metaphor, disturbs the quotidian tone of the previous (which, in turn, had demotically countered the academic tone of the first line).

“I have had to learn the simplest things”

Wow, no longer able (I guess) to let his machinery run his life without his involvement, the narrator has to concentrate, start from a sort of zero.

“I live underneath”

We’ve come to a new stanza. That the narrator says he lives underneath, which the lineation compels us to consider, rather than underneath something, opens a world for me. Certainly, we’re with a narrator deepening through himself (as we would expect from the poem’s consisting entirely of lines in the “i” section of an index).

“I looked up and saw”

This line seems planned to follow the one before it. This sudden strong logic out of the chaos of existence as if to reassure us that life does make sense is one of the virtues of found poetry. Again, a line-break re-locates us, in this case keeping us from a transitive verb’s object, compelling us to consider “saw” as an intransitive verb. The narrator has experienced illumination, not just seen some detail of ordinary life. No big deal if the context set us up for this sort of heightened seeing, but something of a (good) jolt in this zone of reduced context.

“Imbued / with the light”

Yikes, this sentence carries on trouble-free from the previous one.

“I met Death–he was a sportsman–on Cole’s”

The grammar now shatters the logic we seemed for a while to be in, just as “Death” shatters the text’s positive bright ambiance. I can’t help, by the way, thinking of Emily at this point. Death, however, is an absurd, trivial figure, some guy pursuing some conventional sport at some named who-cares-where.

“In cold hell, in thicket, how”

After the intrusion of a line with something of the effect of the famous porter scene in Macbeth, a new stanza, and high rhetoric electrifyingly bleakening the scene. Fascinating how “Cole” quickly colors into “cold hell,” by the way. “In English the poetics became meubles–furniture–”

Another weird shift–to the cold, densely thicketted geography of poetics (in English). “Furniture.” Something inanimate, stupid–but comfortable, for our convenience, to be used. . . . I don’t know the meaning of “meubles” but assume it’s some kind of furniture. Somehow, we are now in a man trying to explain himself in a geography/text trying to explain itself. At least, according to my way of appreciating language poems of this sort, which is partially to take them as exposures of mental states.

“is a monstrance,”

I guess we aren’t meant to sit on the chairs or put anything on the tables in the poem. We are definitely in a darkness and a confusion. “I sing the tree is a heron”

But the narrator can sing. He sings (presumably) of a tree’s resemblance to a heron. In other words, something dark (probably) and solid and motionless, like furniture, has something undark and capable of flight in it. Thus, the stanza ends hopefully, to set up the final one, which begins:

“I sit here on a Sunday”

The tone has gone quiet, conventional–but implicitly celebratory, Sunday being generally a day-off, and devoted to (generally happy) religious services. “It’s so beautiful, life, goddamn death”

The chaos of the poem is resolved with this line. The fragments we’ve been stumbling through, dark and light, are life–which is beautiful in spite of the presence of death.

“it was the west wind caught her up, as”

Because of the line before this one, I’m prepared to read this to be about a woman turned magically into a weightless angel the pleasant west wind is going to give a ride to. Chagall, at his undrippiest. I also read the awe of a man beholding a beautiful woman into the line. An image illustrating the climactic previous statement.

Okay, that was a preliminary once-through I hope some reader will get something out of. I did! Don’t know if I’ll return to it. Probably, so I can use it in a book. Don’t know if I’ll have anything better to say about it then, though.

I’m not ready to say more about the poem now–except that I wondered when I looked at my entry whether I’d mentioned the importance of Crag’s poem’s foundness when I discussed it. I saw I hadn’t. In my megalomaniacal opinion, I think I may be the only critic who has ever discussed the full aesthetic value of foundness. I did this in my discussion, possible two decades ago by now, of Doris Cross’s work–wonderful visual poems brought into being by painting or otherwise defacing, deleting, meddling with dictionary paintings. (I love Nietzsche not only for all he said, brilliantly, that I agree with, but for the megalomaniacal boasts he made about his accomplishments that have turned out to be valid.)

What I said in my Cross piece isn’t handy, so my comments now will probably be a bit incomplete and not as sharply expressed as what I said in it. First off, as anyone would agree and as many I’m sure have said, the quotations from Olson, add his life and writings to Crag’s poem. This is important. But what I think effective appropriation of found materials most importantly does is celebrate the essential logic of the universe. It reminds us that God is in his heaven allowing accidents to make affirmations–even for someone like I who doesn’t believe in God, and understands that accidents don’t really make affirmations, only happen so often that some of them, especially when a keen discoverer has an eye out for them, are bound to do what Crag’s collection does. Another, better way of putting it, is that we are reminded of who wonderfully well the human brain finds ways to give existence meanings, meanings that suggest Meaning.

Okay, not a view you’d think anyone would feel like a demigod for having, but it’s more than anyone else has said about foundness that I know of. And I can’t see how anyone could say it’s wrong.

.

. Poem Consults the Vseineur

.

. However seldom the vseineur

. said “universe” in Poem’s hearing,

. he accepted it,

. however clear it always was

. that it had misspoken.

.

“What most makes the poem a good one, though, is its freshness–the unexpectedness of its infraverbal twist.”

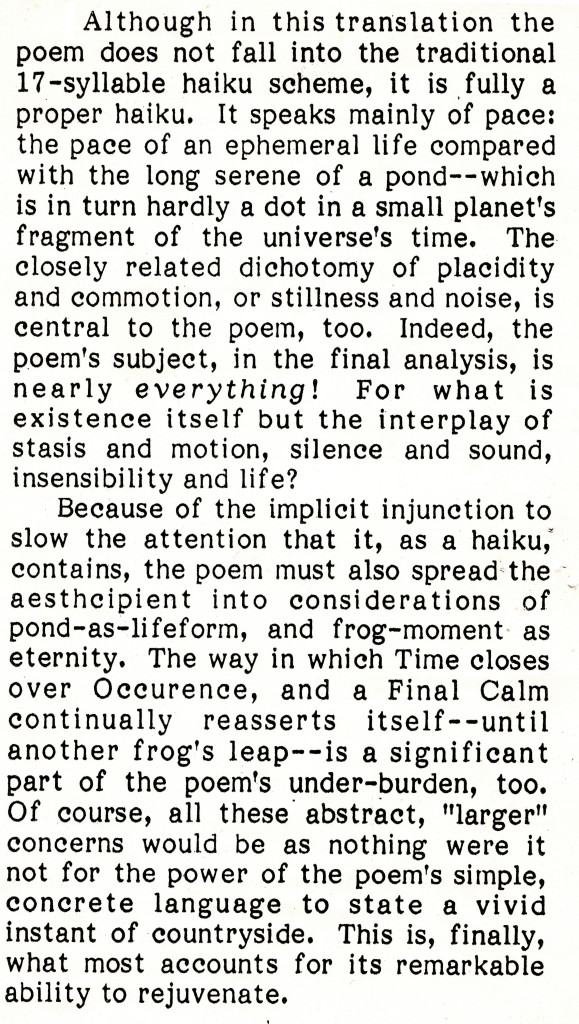

A superb statement of haiku impact, Bob. And I, too, happen to see the haiku potential in pwoermds, especially of the Huth variety. Geof has a genius for them, and some of them have hit me with the same force as the very best haiku.

And thanks for promoting the Canada haiku scene: we usually get lost sometimes in the transborder discussions

Thanks for the kind words, Conrad. I do think I’m pretty good as a haiku-commentator. And I’m always glad to publicize LeRoy Gorman’s excellent haiku review, which seems to me the best periodical around for haiku and haiku-related poems.