Archive for the ‘Marjorie Perloff’ Category

Entry 1167 — Another Null Poetry Discussion

Tuesday, July 30th, 2013

What follows is a response of mine to what some academics are saying about contemporary poetry here.

What I find interesting about the discussion is how representative it is of academics’ discussions of what they take to be the State of Contemporary Poetry–wholly blind, that is, to ninety percent of the various kinds of superior innovative poetry being fashioned outside of university-certified venues–the various kinds of poetry I call “otherstream,” that is. Perloff rather beautifully demonstrates this when she writes, “you can’t very well oppose the Penguin canon by bringing up the names of what are, outside the world of small-press and chapbook publishing, wholly unknown poets.”

Why on earth not?! A competent, responsible critic would be able to find and list whole schools of poets “who are, outside the world of small-press and chapbook publishing, wholly unknown” and show with judicious quotation and commentary why the work of those in them is superior to 95% of the work of living poets in the Penguin. But no, with academics it’s never the superior ignored poets and schools of superior poets that are left out of mainstream anthologies that matter, only certain favored poets already accepted by the academy that have been.

Meanwhile, needless to say, neither Perloff nor her opponent defines her terms nor provides helpful details about the poetry under discussion. In short, one more discussion by people of limited understanding of contemporary poetry, for people with even less knowledge–presented in such a way, alas, as to convince members of the general public that they are actually finding out about the most important poetry of today.

.

Entry 960 — Jump-Cut Poetry

Saturday, December 22nd, 2012

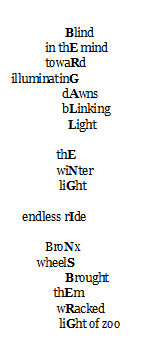

The following is a passage from John Cage’s “Writing for the first time through Howl” (1986) which I appropriated from Marjorie Perloff’s essay at The Boston Review website:

I think Perloff considers this a conceptual poem. To me it’s a simple jump-cut poem, a “jump-cut” in my poetics being defined as “a movement in a text from one idea, image or the like to another with no syntactical bridge between the two.” Thinking about it, I came to the (tentative) conclusion that there are two kinds of (effective) jump-cut poems: (1) procedure-generated ones and (2) moodscape-generated ones. There is just one kind of ineffective jump-cut poem, ones that are neither (1) or (2). Wholly random or essentially random because excessively hermetic crap, in other words.

While into a classifying mood, I divided All of Poetry into (1) Subject-Centered Poetry (what a poem is about) and (2) Technique-Centered Poetry (how a poem is made), with “subject” defined as a combinationof the nature of the subject and the poet’s attitude toward it (tone). Style I consider a technique.

While thinking about many of the comments at The Boston Review website about binaries, I formed one of my own: “Dichotiphobia vs. Rationality.” Further thinking about a few of those comments, and many I’ve been assaulted by, inspired the following observation: “What I notice more and more in discussions of poetry or poetics is how many involved in them prefer not to attack opinions they oppose but the motives of those expressing those opinions.”

I don’t have a high opinion of the Cage passage, by the way. Amusing, and occasionally a juxtapositioning makes something fun happen, but . . . Perloff makes a big deal of its use of appropriation, and it is true that a good deal of what effectiveness it has is due to the way it procedure leads to the randomization of the order of its little locutions–which nonetheless make surprising off-the-wall sense. This, as I suggested long ago while discussing Doris Cross, a superior employer of appropriations Perloff should be more familiar with than she seems to be, conveys a reassuring sense of Nature’s being rational, of something’s being behind it all that unifies our existence’s apparent meaninglessness. No matter how you cut up and re-organize something like Ginsberg’s “Howl,” you’ll never get rid of words’ magical ability to mean. Nor, analogically, of the universe’s.

.

Entry 958 — A Boston Review Symposium

Thursday, December 20th, 2012

A post at New-Poetry sent me to Marjorie Perloff’s essay at the Boston Review website –no doubt not for the first time, for I vaguely remember reading it and not thinking much of it. This time, I quite liked it. Here’s the comment I left about it: “I’ve always faulted Marjorie Perloff for the limited range of the poetry she writes about, but what other poetry critic read by more than a few hundred people would ever write about the poetry of John Cage, Susan Howe and Srikanth Reddy, much less write penetratingly about it as she has in this essay?

“Her choice of appropriation as a center or one of the centers of contemporary “advanced” poetry is interesting but a little off as far as I can see. I, like Christopher M., at once thought of “The Waste Land” when Perloff began speaking of appropriation as something significantly new. But appropriation wasn’t the key device of “The Waste Land”: textual collage was, appropriation being merely a preliminary operation required to make a collage. The jump-cut poetry which resulted due to the influence of “The Waste Land,” which included Ashbery’s work has long been with us.

“What is notable about Susan Howe’s work is not appropriation, but her choice of kinds of material to appropriate, making her, for example, a partly visual poet at times, and it is the mixing of expressive modalities in contemporary poetry where the main action has been for many years, albeit ignored by all the certified critics but Perloff, but rarely more than mentioned in passing even by her.”

Most of the comments made by others to this post seemed to me rather stupid. There were more at another location at the Boston Review website where the Boston Review (which I have not yet put on my list of Enemies of Poetry, but have been close to doing for quite a while) invited 18 poetry-people to:

A Symposium on the Poetic Limits of Binary Thinking

Marjorie Perloff’s essay “Poetry on the Brink” in the May/June 2012 issue rekindled conversation about innovation and canonization in contemporary poetry. To continue and extend the discussion, we cast a wide net and invited 18 poets to address the following question: what is the most significant, troubling, relevant, recalcitrant, misunderstood, or egregious set of opposing terms in discussions about poetics today, and, by extension, what are the limits of binary thinking about poetry? Their responses range from whimsy to diatribe, with meditation, appraisal, tangent, touchstone, anecdote, drollery, confection, wit, and argument in between.

My quick expectation was that the “wide net” would be from sub-mediocre to mediocre . . . but so far, after looking at just four of the contributions to the symposium, I’ve found an intelligent comment. It’s by Ange Mlinko (whom I believe to be a favorite of the Boston Review.) I did not find the comment by Vendler-certified Stephen Burt intelligent, though it prettily plays around the theme. More, I hope, soon.

.

Entry 794 — Uljana Wolf’s “The Applicant [4]”

Monday, July 9th, 2012

I’m analyzing poems by poets Marjorie Perloff deems “experimental” to show how unexperimental they actually are. I find I’m also in the process learning quite a bit about the mainstream’s “cutting edge.” A lot that’s going on there is better than I thought it was–it’s just not poetically adventurous. Here’s one, which is by Uljana Wolf, a poet new to me whose work I had trouble finding on the Internet:

The Applicant [4] blew the interview. Cracked window over a chest too baroquely open for business. Mollusk of rancor in a throat saying should've let him do the talking. Should've left them a foretaste of the whole amalgam. What doesn't kill me makes me wonder. Whatever it was must have tramped off an afternoon laughing so hard it forgot what I looked like with my hat down and left me ghost of infinite back rent to pay.

This is another example of “experimental poetry” that’s nothing but one oddly not-quite-right sentence or partial sentence jump-cutting to another—but doing so musically, with splashfuls of vivid visual imagery. The intent (which may be unconscious) is to engage a reader’s curiosity long enough for the unifying mood the poem is expressing to sink in. It’s interestingly complex, this mood—which includes among much else, what-I-shoulda-done regret, hostility toward the rejecting interviewer (and, it seems to me, the “whatever it was” ultimately in inimical charge of the interviewee’s life), objectivity about the comedy of it all, and melancholy at the thought of the back-rent that will not be paid).

Nothing new here—just a different personality bouncily disdaining transitions. But concluding with a genuine keeper of a pay-off image in the poem’s last four-and-a-half lines.

I’m thinking a good name for the rather large school of Ashberians is “the Neo York School of Poets.”

.

Entry 785 — the Otherstream and the Universities

Saturday, June 30th, 2012

As I said in another entry, Jake Berry has an article in The Argotist Online, edited by by Jeffrey Side, that’s about the extremely small attention academia pays to Otherstream poetry you can read here. I and these others wrote responses to it: Ivan Arguelles, Anny Ballardini, Michael Basinski, John M. Bennett, John Bradley, Norman Finkelstein, Jack Foley, Bill Freind, Bill Lavender, Alan May, Carter Monroe, Marjorie Perloff, Dale Smith, Sue Brannan Walker, Henry Weinfield. A table of contents of the responses is here. I hope eventually to discuss these responses in an essay I’ve started but lately found too many ways to get side-tracked from. The existence of the article and the responses to it has been fairly widely announced on the Internet. Jeff Side says they’ve drawn a lot of visitors to The Argotist Online, ” 23,000 visitors, 18,000 of which have viewed it for more than an hour.” What puzzles both him and me is that so far as we know, almost no one has responded to either the article or the responses to the article. There’s also a post-article interview of Jake that no one’s said anything about that I know of. Why?

What we’re most interested in is why no academics have defended academia from Jake’s criticism of it. Marjorie Perloff was (I believe) the only pure academic to respond to his article, although Jeff invited others to. And no academic I know of has so much as noted the existence of article and responses. I find this a fascinating example of the way the universities prevent the status quo from significantly changing in the arts, as for some fifty years they’ve prevented the American status quo in poetry from significantly changing. Here’s one possible albeit polemical and no doubt exaggerated (and not especially original) explanation for the situation:

Most academics are conformists simply incapable of significantly exploring beyond what they were taught about poetry as students, so lead an intellectual life almost guaranteed to keep them from finding out how ignorant they are of the Full contemporary poetry continuum–they read only magazines guaranteed rarely to publish any kind of poetry they’re unfamiliar with, and just about never reviewing or even mentioning other kinds of poetry. They only read published collections of poems published by university or commercial (i.e. status quo) presses and visit websites sponsored by their magazines and by universities. Hence, these academics come sincerely to believe that Wilshberia, the current mainstream in poetry, includes every kind of worthwhile poetry.

When they encounter evidence that it isn’t such as The Argotist Online’s discussion of academia and the otherstream, several things may happen:

1. the brave ones, like Marjorie Perloff, may actually contest the brief against academia–albeit not very well, as I have shown in a paper I will eventually post somewhere or other;

2. others drawn in by the participation of Perloff may just skim, find flaws in the assertions and arguments of the otherstreamers, and there certainly are some, and leave, satisfied that they’ve been right all along about the otherstream;

3. a few may give some or all the discussion an honest read and investigate otherstream poetry, and join the others satisfied they’ve been right all along, but with better reason since they will have actually investigated it; the problem here is that they won’t have a sufficient amount of what I call accommodance for the ability to basically turn off the critical (academic) mechanisms of their minds to let new ways of poetry make themselves at home in their minds. In other words, they simply won’t have the ability to deal with the new in poetry.

4. many will stay completely away from such a discussion, realizing from what those written of in 1., 2. and 3 tell them. that it’s not for them.

A major question remains: why don’t those described in 2. and 3. comment on their experiences, letting us know why they think they’ve been right all along. That they do not suggests they unconsciously realize how wrong they may be and don’t want to take a chance of revealing it; or, to be fair, that they consider the otherstream too bereft of value for them to waste time critiquing. This is stupid; pointing out what’s wrong with bad art is as valuable as pointing out what’s right with good art. Of course, there are financial reasons to consider: a critique of art the Establishment is uninterested in will not be anywhere near as likely to get published, or count much toward tenure or post-tenure repute if published as another treatise on Milton or Keats. Or Ashbery, one of the few slightly innovative contemporary poets of Wilshberia.

But I think, too, that there are academics who unconsciously or even consciously fear giving any publicity at all to visual or sound or performance and any other kind of otherstream poetry because it might overcome Wilshberia and cost them students, invitations to lecture and the like–and/or just make them feel uncomfortably ignorant because incapable of assimilating it. Even more, it would cost them stature: it would become obvious to all but their closest admirers that they did not know all there is to know about poetry.

Note: I consider this a first draft and almost certainly incomplete. Comments are nonetheless welcome.

.

Entry 774 — The Otherstream, Part One

Tuesday, June 19th, 2012

The Argotist Online has Jake Berry’s essay, Poetry Wide Open: The Otherstream (Fragments In Motion) online and a collection of responses to it including one by me at The Argotist Online. Most of my fellow responders did a good job and are worth reading, John M. Bennett’s was eswpecially good, its only flaw being is shortness. More than half seemed fuzzy to me, and I disagreed fairly strongly with two or three, one of them Marjorie Perloff’s. I’ve always considered Professor Perloff the only visible American critic who has written about poets in the otherstream, and she deserves credit for responding to Jake’s essay–great credit, for keeping aloof from discussions with or about marginals is almost a part of the definition of an academic. She’s written very little about the otherstream, though, and only considered one small portion of it, language poetry (rather poorly, I fear). She’s gotten the toes of one foot into the otherstream, but with her shoe still on, and seems entirely ignorant of those of us wholly immersed in it. Unsurprisingly, I quickly wanted to attack her response. The first thing I did was research the poets she mentioned as “experimental”–about a dozen–on the Internet. Among them was Craig Dworkin. I’d come across his name more than a few times but knew very little of him. It turns out that he is, by my standards, an “experimental” artist–if we take “experimental” to be a synonym for “otherstream,” as Professor Perloff does, but I don’t, “experimental” having become, for me, a uselessly loose “polysemic” word for criticism. Here’s what my search on Dworkin’s name got me:

Fact

By Craig Dworkin

Ink on a 5.5 by 9 inch substrate of 60-pound offset matte white paper. Composed of: varnish (soy bean oil [C57H98O6], used as a plasticizer: 52%. Phenolic modified rosin resin [Tall oil rosin: 66.2%. Nonylphenol [C15H24O]: 16.6%. Formaldehyde [CH2O]: 4.8%. Maleic anhydride [C4H2O3]: 2.6%. Glycerol [C3H8O3]: 9.6%. Traces of alkali catalyst: .2%]: 47%): 53.7%. 100S Type Alkyd used as a binder (Reaction product of linseed oil: 50.7%. Isophthalic acid [C8H6O4]: 9.5%. Trimethylolpropane [CH3CH2C(CH2OH)3]: 4.7%. Reaction product of tall oil rosin: 12.5%. Maleic anhydride [C4H2O3]: 2.5%. Pentaerythritol [C5H12O4]: 5%. Aliphatic C14 Hydrocarbon: 15%): 19.4%. Carbon Black (C: 92.8%. Petroleum: 5.1%. With sulfur, chlorine, and oxygen contaminates: 2.1%), used as a pigmenting agent: 18.6%. Tung oil (Eleostearic acid [C18H30O2]: 81.9%. Linoleic acid [C18H32O2]: 8.2%. Palmitic acid [C16H32O2]: 5.9%. Oleic acid [CH3(CH2)7CH=CH(CH2)7COOH]: 4.0%.), used as a reducer: 3.3%. Micronized polyethylene wax (C2H4)N: 2.8%. 3/50 Manganese compound, used as a through drier: 1.3%. 1/25 Cobalt linoleate compound used as a top drier: .7%. Residues of blanket wash (roughly equal parts aliphatic hydrocarbon and aromatic hydrocarbon): .2%. Adhered to: cellulose [C6H10O5] from softwood sulphite pulp (Pozone Process) of White Spruce (65%) and Jack Pine (35%): 77%; hardwood pulp (enzyme process pre-bleach Kraft pulp) of White Poplar (aspen): 15%; and batch treated PCW (8%): 69.3%. Water [H2O]: 11.0%. Clay [Kaolinite form aluminum silicate hydroxide (Al2Si2O5[OH]4): 86%. Calcium carbonate (CaCO3): 12%. Diethylenetriamine: 2%], used as a pigmenting filler: 8.4%. Hydrogen peroxide [H2O2], used as a brightening agent: 3.6%. Rosin soap, used as a sizer: 2.7%. Aluminum sulfate [Al2(SO4)]: 1.8%. Residues of cationic softener (H2O: 83.8%. Base [Stearic acid (C18H36O2): 53.8%. Palmitic acid (C16H32O2): 29%. Aminoethylethanolamine (H2-NC2-H4-NHC2-H4-OH): 17.2%]: 10.8%. Sucroseoxyacetate: 4.9%. Tallow Amine, used as a surfactant: 0.3%. Sodium chloride [NaCl], used as a viscosity controlling agent: .2%) and non-ionic emulsifying defoamer (sodium salt of dioctylsulphosuccinate [C20H37NaO7S]), combined: 1.7%. Miscellaneous foreign contaminates: 1.5%.

NOTES: “Fact” is an exact list of ingredients that make up a sheet of paper that has been written or printed on, hence the blunt title of the work. It’s a self-reflexive, deconstructed meditation on the act of writing and of publishing, with an emphasis on the materiality of language. Each time Dworkin displays the poem, he researches the medium on which it’s being viewed, changing the list of ingredients. It’s a flexible work in progress, sometimes manifesting itself as a list of the ingredients that make up a Xerox copy, other times listing the composition of an lcd display monitor. (Italicized portion my addition–BG)

Source: Poetry (July/August 2009)

This text presents an interesting challenge to my poetry-taxonomy-in-progress. It is not a poem, by my criteria. But it doesn’t seem to me to be evokature, either. That’s what I call prose that attempts to evoke images and/or emotions the way poetry does but has no lineation, or anything like lineation. What it clearly is, is a work conceptual art (which I consider inspired). For now I will consider it “conceprature,” a sibling of “evokature” (what “prose poems” are) and, like the latter, a subcategory of prose.

My pluraphrase (i.e., full expression of what a poem is, does and says) of it is inchoate right now, or less than inchoate. I’ll kick it into my under-consciousness, for now. With luck, it’ll turn into something I can work at least a tentative appreciation of “Fact” into. In the meantime, I have to acknowledge that a top-level member of the American Poetry Establishment has done a good deed for me (I mean Professor Perloff, not Craig Dowrkin, also an academic who has done a good deed for me). Not sure I can get over that.

.