Archive for August, 2010

Entry 207 — A Day in the Life of a Verosopher

Tuesday, August 31st, 2010

Random thoughts today because I want to get this entry out of the way and work on my dissertation on the evolution of intelligence, or try to do so, since I’m still not out of my null zone, unless I’m slightly out but having trouble keeping from falling back into it.

First, two new Grummanisms: “utilinguist” and “alphasemanticry.” The first is my antonym for a previous coinage of mine, “nullinguist,” for linguist out to make language useless; ergo, a utilinguist is a linguist out to make language useful. By trying to prevent “poetry” from meaning no more than “anything somebody thinks suggests language concerns” instead meaning, to begin with, “something constructed of words,” before getting much more detailed, for example.

“Alphasemanticry” is my word for what”poetry” should mean if the nullinguists win: “highest use of language.” From whence, “Visual Alphasemanticry” for a combination of graphics and words yielding significant aesthetic pleasure that is simultaneously verbal and visual.”

I popped off today against one of Frost’s “dark” poems, or maybe it is a passage from one of them: “. . . A man can’t speak of his own child that’s dead”–the kind academics bring up to show Frost was Important, after all. “Wow,” I said, “Wow, he confronts death! He must be major! “ I then added, “Frost is in my top ten all-time best poets in English that I’ve read but not for his Learic Poems.”

James Finnegan then corrected me, stating (I believe) that the poem didn’t confront death but showed its effects. I replied, “Okay, a poem about the effect of death on two people. What I would call a wisdom poem. I’m biased against them. I like poems that enlarge my world, not ones that repeat sentiment about what’s wrong with it, or difficult about it. Frost knew a lot about reg’lar folks, but I never learned anything from him about them that I didn’t already know. In other words, I’m also somewhat biased against people-centered poems. But mostly, I don’t go to poems to learn, I go to them for pleasure.”

I would add that I’m an elitist, believing with Aristotle that the hero of a tragedy needs to be of great consequence, although I disagree with him that political leaders are that, and I would add that narrative literature of any kind requires either a hero or an anti-hero (like Falstaff) of great consequence.

I’m not big on poems of consolation, either.

I find that when I have to make too trips on my bike in a day, it zaps me. I don’t get physically tired, I just even less feel like doing anything productive than usual. Today was such a day. A little while ago i got home from a trip to my very nice dentist, who cemented a crown of mine that had come out (after 24 years) back in for no charge, and a stop-off at a CVS drugstore to buy $15 worth of stuff and get $4 off. I actually bought $18 worth of stuff, a gallon of milk and goodies, including a can of cashews, cookies, candy, crackers . . . Living it up. Oh, I did buy cereal with dried berries in it, too.

My other trip was to the tennis courts where I played two sets, my side winning both–because of my partners. I’m not terrific at my best, and have been hobbled by my hip problem for over a year. It may be getting slightly better, though–today I ran after balls a few times instead of hopped-along after them. I’m still hoping I’ll get enough better to put in at least one season playing my best. Eventually, I’m sure I’ll need a hip replacement but there’s a chance I won’t have to immediately.

I’ve continued my piece on the evolution of intelligence, but not done anything on it today. now fairly confidentI have a plausible model of the most primitive form of memory, and its advance from a cell’s remembering that event x followed action a and proved worth making happen again to a cell’s remember a chain of actions and the result. That’s all that our memory does, but it’s a good deal more sophi- sticated. I think I can show how primitive memory evolved to become what my theory says it now, but won’t know until I write it all down. (It’s amazing how trying to write down a theory for the first time exposes its shortcomings.) If I can present a plausible description of my theory’s memory, it will be a good endorsement of it. No, what is much more true is that if I am not able to come up with a plausible description, it will indicate that my theory is probably invalid.

Entry 206 — Shakespeare’s Sonnet 97

Monday, August 30th, 2010

Over at the Forest of Arden, I had a lot of trouble figuring out Shakespeare’s Sonnet 97, then suddenly put together an explication of it I liked so much, I’m posting it here.

Sonnet 97

How like a Winter hath my absence beene

From thee, the pleasure of the fleeting yeare?

What freezings haue I felt, what darke daies seene?

What old Decembers barenesse euery where?

And yet this time remou’d was sommers time,

The teeming Autumne big with ritch increase,

Bearing the wanton burthen of the prime,

Like widdowed wombes after their Lords decease:

Yet this aboundant issue seem’d to me,

But hope of Orphans, and vn-fathered fruite,

For Sommer and his pleasures waite on thee,

And thou away, the very birds are mute.

Or if they sing, tis with so dull a cheere,

That leaues looke pale, dreading the Winters neere.

* * * * *

Okay, here beginnith my explication:

How like a Winter hath my absence beene

From thee, the pleasure of the fleeting yeare?

What freezings haue I felt, what darke daies seene?

What old Decembers barenesse euery where?

the quickly passing year, is like being in winter.

Coldness, darkness, December’s bareness seem

everywhere to me, as everyone agrees. Vendler

adds that Shakespeare is picturing an “imaginary

winter.” He isn’t. He’s just making a simile.

And yet this time remou’d was sommers time,

The time we’ve been apart was summer.

Still straightforward and undebatable.

The teeming Autumne big with ritch increase,

Bearing the wanton burthen of the prime,

Like widdowed wombes after their Lords decease:

NoSweatShakespeare, a website with sonnet analyses, put

an “and” at the beginning of this. I wouldn’t, but the

“and,” which I’d previously thought of, too, then discarded

helped me accept this as just a continuation of the previous line:

I missed, Joe, Sally . . . The speaker was gone during the

end of summer and much of autumn. . . So, to backtrack:

And yet this time remou’d was sommers time,

The teeming Autumne big with ritch increase,

Bearing the wanton burthen of the prime,

Like widdowed wombes after their Lords decease:

The time I have been away from you was

summer followed by autumn, which was

bearing a good crop like women bearing dead

husbands’ offspring.

Yet this aboundant issue seem’d to me,

But hope of Orphans, and vn-fathered fruite,

However fine the autumn, abundant and promising

seemed to me a dreary place for orphans and fruit

no love-making had produced, which is about

as nearly everyone would have it, I’m sure.

For Sommer and his pleasures waite on thee,

For, imaginatively, it’s still summer, because the realest

summer although it wasn’t exactly hers) is still waiting for

the addressee’s to continue.

Confession: I got the contrast of what’s imagined, what real,

from Vendler.

And thou away, the very birds are mute.

Or if they sing, tis with so dull a cheere,

That leaues looke pale, dreading the Winters neere.

Back in the real world, where it’s autumn, the birdies

and the leafies are sad, thinking about the nearness

of winter.

Have I more or less finally gotten it? Regardless, I feel

quite buoyed to have come up with what I did. Later I

discovered Robert Stonehouse had much the same

interpretation as mine, but I think I did better on

“summer/ Autumn” and “summer waits” than he,

so remain happy about my achievement.

Entry 205 — Evolution of Intelligence, Part 2

Sunday, August 29th, 2010

At this stage of the evolution of intelligence a lot of minor advances would be made: multiplication of reflexes, the addition of sensors sensitive to the absence of a stimulus, the combining of more sensors and effectors so, perhaps, a purple cell with white dots and smell B and a long flagellum will be pursued if the temperature of the water is over eighty degrees but not if it is under.

By this time, something of central importance had to have happened, or be ready to happen: the evolution of sensors sensitive to pain and pleasure. For that to happen, “endo-sensors” (sensors sensitive to external stimuli) would have to have broken free of the cell membrane to become potential “intra-sensors.” And somehow become sensitive to a chemical due to damage to the cell mem- brane–probably excessive water (a biochemist would know). Or maybe the infra-cell might become sensitive to pieces of the membrane which it would never have contact with unless the membrane were damaged. If the intra-sensor were attached to an away-from effector, natural selection would select it because of its value in helping its cell get away from whatever had damaged is membrane.

Eventually similar intra-sensors connected to toward effectors would become sensitive to some by-product, say, of a successful hunt–something eaten but not digested, that would cause the cell to pursue whatever it had gotten a good taste of. I’m now going to name all such components of a cell that carry out functions like those of the sensors and effector “infra-cells” to make discussion easier. Let me add the clarification that the connections between sensors and effectors may begin as physical channels but will soon almost surely come to be made by precursors of neuro-transmitters: i.e., a sensor with “connect” to its effector by a distinctive chemical that only the effector recognizes and is activated by. The cell’s cytoplasm will act as a primitive synapse.

Various other “neurophysiological” improvements should soon also occur. One would be an intra-sensor’s gaining the ability to activate a toward effector when it senses pleasure but activate an away-from effector when it senses pain. The accident resulting in such an infra-cell would not be too unlikely, it seems to me: simply the fusion of two cells, one sensitive to pain and connected to an away-from effector, the other sensitive to pleasure and connected to a toward effector. Obviously an evolutionary improvement.

It also seems likely to me that intra-sensors would evolve sensitive to the activation of effectors. They would connect to other infra- cells carrying out reactions to, say, a successful capture of prey: a toward effector becomes active due to signals from a sensor sensitive to a certain kind of prey, in which case the outcome should be dinner, so a sensor sensitive to the effector’s activation which is connected to some infra-cell responsible for emitting digestive juices or the like, would be an advantage.

Certain other infra-cells should evolve to allow the step up to memory, but right now I can’t figure out what they might be, so will stop here, for now.

Entry 204 — Learning from Others’ Poetry

Saturday, August 28th, 2010

To take care of today’s entry without much work, I’m posting something I wrote for New-Poetry about what a would-be poet can learn from reading other poets’ work.

The crossfire about learning how to use blank verse from Frost got me wondering what one has to learn to be a poet. What meter and what I call melodation”–rhyme, alliteration, etc. are, for many people. Lineation for everybody. I tend to think that once you learn what these things are, there’s nothing more to learn about them. The rest of using them for poetry is simply to find good words to put into them.

After thinking more, I realized that developing an awareness of the various subtleties

involved in best use of these devices would be something learnable–through exposure to poets like Frost who use the devices well. Who might make you suddenly realize what a device you underrated could do.I still like best those poets who are doing something other poets, and I, are not–those I

can steal new devices from. Such poets are very rare. Cummings, some of the early

language poets, Pound, Stein, maybe Williams for . . . unfiguration? Eliot/Pound or who?

for the jump-cut.Otherwise a major thing all poets have to learn is what cliches are. Cliches of expression, idea, subject matter, technique. Read a lot and learn to–sorry–make it new. What else is there to learn?

Entry 203 — Random Thoughts

Friday, August 27th, 2010

Random thoughts today because I want to get this entry out of the way and work on my dissertation on the evolution of intelligence, or try to do so, since I’m still not out of my null zone, unless I’m slightly out but having trouble keeping from falling back into it.

First, two new Grummanisms: “utilinguist” and “alphasemanticry.” The first is my antonym for a previous coinage of mine, “nullinguist,” for linguist out to make language useless; ergo, a utilinguist is a linguist out to make language useful. By trying to prevent “poetry” from meaning no more than “anything somebody thinks suggests language concerns” instead meaning, to begin with, “something constructed of words,” before getting much more detailed, for example.

“Alphasemanticry” is my word for what”poetry” should mean if the nullinguists win: “highest use of language.” From whence, “Visual Alphasemanticry” for a combination of graphics and words yielding significant aesthetic pleasure that is simultaneously verbal and visual.”

I popped off today against one of Frost’s “dark” poems, or maybe it is a passage from one of them: “. . . A man can’t speak of his own child that’s dead”–the kind academics bring up to show Frost was Important, after all. “Wow,” I said, “Wow, he confronts death! He must be major! “ I then added, “Frost is in my top ten all-time best poets in English that I’ve read but not for his Learic Poems.”

James Finnegan then corrected me, stating (I believe) that the poem didn’t confront death but showed its effects. I replied, “Okay, a poem about the effect of death on two people. What I would call a wisdom poem. I’m biased against them. I like poems that enlarge my world, not ones that repeat sentiment about what’s wrong with it, or difficult about it. Frost knew a lot about reg’lar folks, but I never learned anything from him about them that I didn’t already know. In other words, I’m also somewhat biased against people-centered poems. But mostly, I don’t go to poems to learn, I go to them for pleasure.”

I would add that I’m an elitist, believing with Aristotle that the hero of a tragedy needs to be of great consequence, although I disagree with him that political leaders are that, and I would add that narrative literature of any kind requires either a hero or an anti-hero (like Falstaff) of great consequence.

I’m not big on poems of consolation, either.

Entry 202 — Back to Gladwell’s 10,000 Hours

Thursday, August 26th, 2010

Certain cranks are questioning the possibility that Shakespeare wrote the works attributed to him on the grounds that he could not have gotten the 10,000 hours of practice at his craft Malcolm Gladwell says every genius needs. What I want to know is, if Shakespeare had his ten thousand hours when he wrote the Henry VI trilogy, where does it show? There are serious scholars out there who think Heminges and Condell were lying when they said he wrote them. Many mainstream critics won’t accept that he wrote certain scenes in them.

I claim that any reasonably intelligent non-genius actor of the time could have used the historians of the time, as Shakespeare did, to have written them. Add, perhaps, a cleverness with language that some 14-year-olds have. The only way his histories improved after the trilogy was in the author’s becoming better with words, through practice, of course, but only what he would have gotten from contin- uing to write plays (and doctor plays and–most important–THINK about plays), and getting interested enough in a few of his stereotypical characters to archetize them as he did Falstaff.

It seems to me that the requirements for being a playwright are (1) a simple exposure to plays to teach one what they are; (2) the general knowledge of the world that everyone automatically gets simply by living; (3) the facility with the language that everyone gets automa- tically from simply using them all one’s life. The rank one as a playwight will depend entirely on his inborn ability to use language, and his inborn ability to empathize with others, and himself. Of course, the more plays he writes, the better playwright he’ll be, but I’m speaking of people who have chosen to make playwriting their vocation (because they were designed to do something of the sort).

I speak out of a life devoted to writing and having read biographies of dozens of writers. I would never be able to agree that I’m wrong on this.

Entry 201 — Evolution of Intelligence, Part One

Wednesday, August 25th, 2010

A week or so ago, I read an article in Discover about the shrinkage of the human brain over the past 20,000 or more years. Well-written, fairly interesting piece thought didn’t go very deep because only certified authorities were consulted for explanations as to what was behind the shrinkage. I was provoked enough to scribble a list of eight possible reasons for the shrinkage, planning an essay on the subject, for the heck of it mainly, but also to send to the author of the Discover article in hopes she might find it interesting, and perhaps do another article on the subject for some other magazine, and this time mention me. Or think enough of what I wrote to get my views when doing another article on the brain. Yeah, more delusional day- dreaming on my part. But just to write an essay on the shrinkage seemed to me a good idea. Another achievement, if I finished it, and a chance to clarify my thinking about my knowlecular psychology, too. Also perhaps enough fun to break me out of the dry spell I’ve been going through as a writer.

This it did, for a day, for I wrote 1150 words the day I wrote the above. After that, I wrote a few hundred words about it daily for a few days, then missed a day. That was okay with me because the reason I slowed down, then wrote nothing was that I thought I needed to back way up and explain intelligence, starting with its evolution. A tough job even if I could remember as much of my theory as I needed to.

After a day or two of inactivity, I managed a few words a day four a couple of days. They were of much value but they did start awakening my understanding of my theory. Eventually, I got the beginnings of my take on the beginnings of intelligence, if by intelligence we mean “choice of behavior” as opposed to random activity.

Let’s begin with the first living cell, a protozoan.” It moves randomly through water. Eventually it accidently acquires a sensitivity to light, let’s say, although it could be salt denisity or temperature, it doesn’t matter. So, it has the prototype of a nervous system, a single sensor sensitive to light. The next consequential accident will be its evolving a component that makes it move in some direction as opposed to being moved by environmental forces. Call it an “effector.” It may evolve this before it evolves a sensor, it doesn’t matter, What matters is that eventually many protoazoa will have non-functioning but not seriously biologically disadvantageous nervous-systems. They’ll be superior (no quotation marks: they will have the potential for intelligence other protozoa lack, so will be superior to them, if not to invincibly egalitarians halfwits, whom I’m insulting here in the hopes they go away and I won’t have to hear the nonsense I eventually would if they didn’t). Ergo, I will call them “alphzoa.”

The first key accident leading to intelligence will be an alphazoan’s forming a linkage forming its light-sensor and effector, allowing the former to activate the latter.

If the effector causes movement toward light, and light is beneficial–as perhaps a source of energy–alpazoa with this capacity will soon become dominant. Alphazoa which light causes to move away from light will die out. Or perhaps evolve differently, finding something in darkness that makes up for lack of light–concealment from prey, maybe. In any case, a functional, useful nervous system will have come into being, or what I’d call simple reflexive intelligence. The march to Us hath commenced. Eventually some sensor will evolve that is sensitive to the color, say, of one of the alphazoan’s prey and links with an effector causing the alphzoa to move toward the prey, a “toward-effector.” Ditto, a reflex with an “away-from effector” attached to a sensor sensitive to the color or some other characteristic of some kind of predator on the alphazoan. Not a technical advance, but certainly a big jump in improving the alphazoa’s biological fitness.

At the same tiime, alphazoas will naturally be increasing their numbers of such reflex pairs. Eventually, there’d have to be a sizable group of alphazoa with several effective reflex pairs, to significantly improve their chances of those pairs lucking into new combinations of high importance. A good example would come about when an organism preying on the alphazoa evolved the same coloring as the alphazoa’s prey. Misfits without the toward-gray reflex would suddenly have an advantage on those with it. Some such misfits would develop withdraw-from-gray reflex pairs. Eventually some of them would also develop a sensor sensitive to something the prey had that the predator did not have but the gray prey did, smell A, say, and connect it to the move-toward effector.

Conditions would then be right for the next essential evolutionary step toward full intelligence. Alphazoa would exist, each of which has an away-from-grey reflex and a toward-smell A reflex. So they would flee from gray cells without smell A–but both flee from and go after gray cells with smell A. Safety, but no meal unless the prey swam into them. This problem (or one like it) would be crucial in making conditions right for the advent of a rudimentary form of “choice,” however.

I’m sure messy partial solutions would come about and probably clever mechanisms different from the one I think may have carried the day. But something along the lines of the solution I’m about to propose had to have occurred. It would depend on the evolution of inhibitors–and we know inhibition has a major role in the nervous system.

An inhibitor is device which prevents any effector it is connected to from acting just the way a sensor causes the activation of any effector it is connected to, Like everything else, it would pop up by chance but persist when it happened, say, to be connected to a smell-A sensor and inhibited an away-from effector. Ergo, the alphazoa blessed with such an inhibitor would flee a gray cell which lacked smell A, but go after such a cell if it had smell A, because it sinhibitor would prevent the away-from effector from preventing it from doing that.

So, life will now have achieved the ability to choose between advancing or withdrawing in the direction of a gray cell. It will still be a very primitive computer, but with something like intelligence, anyway.

*** That’s as far as my coherent writing got. Extremely difficult to write although what I said could probably not be more simple and unoriginal.

Entry 200 — Can a Non-Grind Become a World-Genius?

Tuesday, August 24th, 2010

There have always been mediocrities who desperately want to believe that one can become great if only one applies oneself. Even more partial to the idea are totalitarians, who–if training is shown to be everything–will have a good chance of being allowed to totalitarianly force training on unfortunate children. Malcolm Gladwell is no doubt one of them. In his recent book, Outliers: The Story of Success, he argues that high achievement is only possible for grinds, and that there is no such thing as what he calls “an outlier,” an individual who rises to the top without being a grind. To support his view, he presents a study (by someone named Ericsson) of violin students at a Berlin musical academy, tracking them from age five to age twenty. All were gifted, all stayed with the violin for fifteen years. Here’s what Gladwell says of the study (which I got from a post to one of my Shakespeare Authorship Debate discussion groups, by a Marlovian):

By the age of twenty, the elite performers had each totalled ten thousand hours of practice. By contrast, the merely good students had totalled eight thousand hours, and the future music teachers had totalled just over four thousand hours.

Ericsson and his colleagues then compared amateur pianists with professional pianists. The same pattern emerged. The amateurs never practiced more than about three hours a week over the course of their childhood, and by the age of twenty they had totalled two thousand hours of practice. The professionals, on the other hand, steadily increased their practice time every year, until by the age of twenty they, like the violinists, had reached ten thousand hours.

The striking thing about Ericsson’s study is that he and his colleagues couldn’t find any “naturals,” musicians who floated effortlessly to the top while practicing a fraction of the time their peers did. Nor could they find any “grinds,” people who worked harder than everyone else, yet just didn’t have what it takes to break the top ranks. Their research suggests that once a musician has enough ability to get into a top music school, the thing that distinguishes one performer from another is how hard he or she works. That’s it. And what’s more, the people at the very top don’t work harder or even much harder than everyone else. They work much, much harder.

My response:

I’ll have to read his book in order to pin down Gladwell’s errors. I probably won’t bother because my life experience refutes him. Good grief, any reasonably academically clever child finds himself surrounded throughout his school years with kids who actually have to study to get B’s when he can sleep through classes and get A’s. I don’t find it surprising that Ericsson found no grind who got in his ten thousand hours of practice and was still lousy. That’s obviously because lack of talent for playing the violin is so obvious that even a grind will soon find that there are things he simply can’t do, and give up. It’s easier for a grind to find ways to fake it in intellectual fields and put in his ten thousand hours, and become certified, and rise in his field thanks to the aid of fellow mediocrities. Good grief, just look around at the academic authors of dozens of books apiece all of whom are third-rate at best.

That Ericsson found no one who equaled the grinds without putting in ten thousand hours does surprise me. I suspect his sample was too small to include any naturals, who would no doubt be very rare.

As usual, anti-Stratfordians have no idea how Shakespeare could have gotten his ten thousand hours because they don’t know anything about epistemology, or the creative process, or what specifically is needed by a would-be dramatist. The believe ten thousand hours of formal study is needed, for they have no idea what informal study is. I do tend to think there might be something to the idea that excellence in any field requires a lot of practice, but that–one–the ability to devote massive amounts of time to a field is genetic, and–two–there are many ways to devote oneself to a field.

When I was the only one in my high school class (400 or so, some of whom ended up in Harvard, Princeton, Berkeley, Yale, etc.) to reach the semi-finals of the Merit Scholarship competition, those in my class who didn’t know me well but knew I paid little attention to my teachers in class, got almost all my homework done during class or in study hall, and thought there was something wrong with anyone who had to study. Ergo, I must have photographic memory.

The truth, though, is that I had been diligent in an informal way: I’d gotten in thousand of hours of random reading outside school, some of it of mildly advanced texts, and done something else that should count but would not likely be counted by someone like Gladwell, I THOUGHT about things. I wrote my first full-length play at 19–but by that time I’d probably written hundreds of scenes in my head starring me–and, at the beginning, Donald Duck and his three nephews. The play wasn’t very good, but I wrote two more plays before I was twenty, and the second of these was, I believe, promising. But not good, though certainly as good in many ways as Titus Andronicus.

One can certainly argue that I was not a great dramatist, and the reason for this was that I didn’t have enough proper training to be one, but the question is still how I’d gotten to where I could write literate full-length plays at the age of 19.

My only serious point here is to suggest how easily Shakespeare could have reached the level he did in his twenties. Lots of reading, and lots of THINKING. He also had, apparently, one huge advantage over me: he probably acting as an amateur of became an actor, then play doctor, the playwright, for an acting company while still young.

I’m with Felix (a Stratfordian who posted on the subject), by the way, in claiming that every reasonably intelligent twenty-year-old will have had ten thousand hours training in language, and that that is sufficient for any kind of literary vocation. All artists by twenty will have put in ten thousand hours or more in the study of human beings, too, so will be able write about them or depict them in paint.

Entry 199 — The Origin of Intelligence

Monday, August 23rd, 2010

A week of so ago, I read an article in Discover about the shrinkage of the human brain over the past 20,000 or more years. Well-written, fairly interesting piece though it didn’t go very deep because only certified authorities were consulted for explanations as to what was behind the shrinkage. I was provoked enough to scribble a list of eight possible reasons for the shrinkage, planning an essay on the subject, for the heck of it mainly, but also to send to the author of the Discover article in hopes she might find it interesting, and perhaps do another article on the subject for some other magazine, and this time mention me. Or think enough of what I wrote to get my views when doing another article on the brain.

Yeah, more delusional day-dreaming on my part. But just to write an essay on the shrinkage seemed to me a good idea. Another achievement, if I finished it, and a chance to clarify my thinking about my knowlecular psychology, too. Also perhaps enough fun to break me out of the dry spell I’ve been going through as a writer.

This it did, for a day, for I wrote 1150 words about it Friday. Four or five hundred Saturday and another six hundred yesterday.yesterday. In the process, though, I veered into the evolution of intelligence and suddenly have too many problems to solve. What I thought I’d do a short essay about needs a short book to do right.

Oddly enough, one of my larger problems is defining intelligence. All I’m sure of is that it came long before brains evolved. I think it may just be “the ability of an organism to choose reactions to a situation based on more than one piece of knowledge. Presence of predator equals flee would be pre-intelligence, or a reflex action. Presence of predator when one has a spear equals destroy equals intelligence. Even though in the final analysis all our behavior is reflexive. It’s just that some behavior’s stimulus is both temporally and spatially larger than another’s.

Entry 198 — The Kelly Writers House

Sunday, August 22nd, 2010

Earlier today Al Fireis passed on the following announcement to New-Poetry:

“The people of the Kelly Writers House are pleased to announce – in addition to many hundreds of other readings, symposia, performances, seminars, workshops, netcasts & community outreach programs – this year’s three Writers House Fellows:

“Does the house ever do artist outreach programs–by giving an artist with something fresh to say in a highly visible forum, for pay? That said, I have to say that Albee has proven himself not an enemy of the arts by supporting (with money, I believe) the Atlantic Arts Center in Florida. It mainly helps artists who don’t need help, but pays them to help artists (like me) who do need help, as sort of associates working together under the leadership of the artist who doesn’t need help. If that’s the way it is still run. I learned Photo Shop there, a program I couldn’t afford though I eventual was able to get a cheap version of it, Paint Shop. It was a key to my development as a visual poet.

“Of course, my getting into one of the Atlantic Arts Center programs was a fluke. Albee himself had used his influence to get Richard Kostelanetz a slot as a master artist, and Richard picked truly marginal associates. All other master artists selected, so far as I know, have been mainstreamers, with mainstream associates.

“Perloff, to give her credit, helped language poetry when it was otherstream. She may well have done this opportunistically: Vendler had used Ashbery to stand out, so she grabbed Bernstein, or the language poetry people in general. Which is fine with me. I’d love such an opportunits to do the same for visual poetry, and will never understand why none has. A few have tried but not gotten far with it. Probably because few visual poets are academics, and thus close in one way to the mainstream. More language poets had academic clout long before they had literary clout.

“As for Cheever, I can’t imagine what she has to say. Reminiscences about her father, a one-time noted mainstreamer.

“Sorry for the Me-stuff, but the name Albee set it off. Strangely important name in my life even though I’m not a great admirer of his plays, and probably have little in common with him in other ways, and once disliked him. I saw what may have been the premiere of his Zoo Story, along with Krapp’s Last Tape; disliked Zoo Story, very much liked Krapp’s Last Tape. Greenwich Village Theatre when I was a teen-ager just learning my way into the arts, with high school buddies I’m still friends with, one of whom because a actor who got by but never became well-known, another who became a very wealthy Manhattan corporate lawyer, and a third who became a wealthy Bevery Hills cataract man.

“Sorry, again, but I’m feeling talkative–”writative?” Took a pain pill with an opium derivative in it an hour ago. Hip pain I’ll probably need hip replacement surgery to get rid of. Also, I live alone.

“You know, I’m against the government’s subsidizing anything whatever, but if they’re going to subsidize the arts, I think they should make it a rule that any organization getting government money, even in the form of tax breaks, should be required by law to give at least one position a year like the ones Kelly House is giving to Albee and the others to someone who has never been given such a position by such an organization. Or never gotten more for taking such a position than, say, a hundred dollars.

“One of my daydreams is of becoming a literary super-star invited all over to make guest appearances, and refusing to for a given organization until that organization has invited four or more marginal artists (or critics) to make similar appearances, paying them what it’d pay a super-star. It would be going too far to make them do that before inviting any well-known artist or critic; I wouldn’t require more than their doing it for just one unknown if it weren’t the practice never to help an unknown (who doesn’t have somebody of influence pushing for him to be invited, or is representative of some allegedly underprivileged group, aside from experimental artists.

“Hey, looks like I’ve written my blog entry for today. I’ve been so out of it for many months that I’ve been trying to force myself to at least write a blog entry every day. Have done so for over a week. “

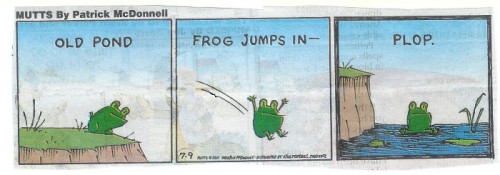

this has been up for several days on Issa’s Untidy Hut

I am fairly certain it is Watt’s translation of The Frog Poem

which I came away with:

so many frogs

in one pond

croaking

Now make it into a comic strip, Ed!

Thanks for continuing to visit–and for your previous good wishes. I continue to improve–but now my lawn mower won’t work! I should make a haiku about that but won’t.

I got one if I can find your email address will send it to you

meanwhile I just sit out on my huge back deck

&watch the weeds grow and my push-mower rusting.

old push mower

rusting

among the weeds

I wonder how a comic strip like “Mutts” survives. This particular strip is actually funny, while most are not. I think it gets by on appealing to sentimental pet lovers, who just want cute dog and cat pictures, and maybe some on the the strength of its draftsmanship (though this strip is rather weak in that department, and maybe the coloring doesn’t help). And what’sh the deal with that shpeech impediment? Yeesh. Maybe it one all cats have when they learn to talk. On the other hand, i think the artist is a Buddhist, given some of the stuff he quotes in his strips, so he gets some diversity points.

Anyway, here’s my response to that pond/frog poem, in the form of a hay(na)ku, which you can imagine William S. Burroughs reading:

the old pond,

a frog

croaks.

endwar

I think the drawing of Mutts is superior, intentionally reminiscent of Popeye, just right for its kind of comic strip. Much of the humor is simple enough–many puns, for example. Otherwise, I go along with your impressions.

Poop on your debasement of the old pond haiku. Some pipple got no respeck.