Archive for the ‘Poetry’ Category

Entry 1755 — Robert Frost

Tuesday, March 17th, 2015

The best English-language poets are named Robert, but Robert Frost would have been a favorite poet of mine even if he’d been named Adolph. I consider his “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” the best straitverse poem I’ve encountered. So it was nice to see a review of a newly available volume of his letters in the latest issue of The New Criterion–although no surprise, considering how little interest to it poets younger than dead for forty years, figuratively if not literally, are. It was good, too, to learn that the reviewer, Andrew Hamilton, feels this collection of letters “should serve as a thorough corrective to (the view of Frost’s main biographer, Lawrence) Thompson as a “monster”–although I never have thought of him as anything but a sometimes cranky decent man, myself . . . although he’d be on my list of great poets however bad a human being I agreed he was, and that comes close to all that counts with me.

I bring him up not only to get another blog entry out of the way so I can go back to bed but because the quite interesting review of his letters mentions his writing in one of them about how appropriate the language of his poetry’s is “to the virtues I celebrate.” “Virtues.” Didacticism. Poetry with a moral. Horace’s stupid pronouncement that poetry should teach as well as please–although it usually comes up in reverse to the way I have it, reminding people that poetry should please as well as teach. I’m an extremist here although I contend I usually seek the middle between extremes–unless I go for both extremes simultaneously. I believe poetry should give pleasure, period. Any teaching it tries to do will only distract from that.

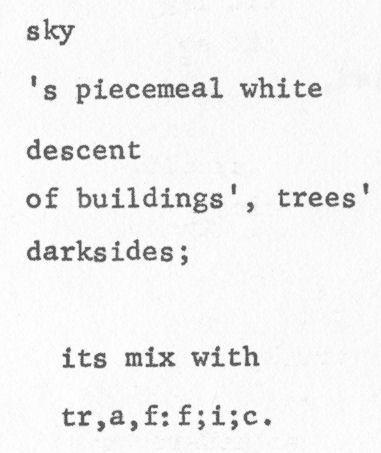

But the first poem of my own I thought okay (the one in my 14 and 15 March entries) pushed the virtue of wilderness versus ordered sterility. My one about “tr,af:fi;c.” had nothing to with any virtue, though. Which doesn’t mean someone trying to force it into everything could charge it with celebrating the virtue of winter serenity or something. It does that. A higher virtue it can be said to honor is the simple virtue of sensual awareness. Perhaps at an even higher level it expresses my own religion’s highest virtue, reverence of the universe. Urp.

But all this indicates is that virtue is a part of any poem to some degree. Ergo, to permit discussion of virtue in a poem to be of value, one must distinguish explicit references to standard abstract virtues like honesty and tolerance (two of my favorites) from implicit references, implicit reference, that is, which the context of the poem fails explicitly to suggest may be there. Only poems concerned with the first kind of virtue should count as moral poems.

I use the same kind of reasoning to justify my contempt for the frequent declaration that all poems are political.

By this reasoning, I consider my favorite Frost poems “lyrical,” which I use for poems the main intent of which is to give aesthetic pleasure, and little or no moral improving. Ergo, “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” is not a moral poem–although it does convey a moral meaning: duty before pleasure, or something about the importance of fulfilling responsibilities. Frost’s use of this moral message is brilliant, though: it’s only a frame to attach his much more interesting characterization of his persona to, whereas that characterization is only a ladder to a scene (in a [mood]) . . . in Time. But it’s all also in a poem, a poem that is a box of sounds as another sense that poem makes.

My traffic poem goes directly to the scene, with a box of punctuation taking the place of Frost’s box of sounds, and my poem as a whole doing less than Frost’s–but, I would argue, more for poetry.

Actually, my poem has a persona, too. He just isn’t physically in the poem the way Frost is in his. Nor is he brought anywhere near alive. But he’s watching the sky’s descent. He’s punctuating along with the traffic. . . .

.

Entry 1753 — My 1st Full-Scale Hero in Poetry

Sunday, March 15th, 2015

In my little-selling Of Manywhere-at-Once, Keats was one of the six canonized poets I wrote a chapter about. Yeats, Pound, Stevens, Cummings and Roethke were the others. I suddenly realize that Stevens was the last of them to become a hero in poetry of mine–around 35 years ago. None since. Nor, that I can think of, any literary heroes of any kind since then. Heroes of verosophy? Perhaps. More likely, no: because I don’t think I have any genuine verosophical heroes. The one who comes closest is Nietzsche, but I consider him a literary hero. I’ve greatly admired a lot of verosophers–Archimedes, Aristotle, Darwin, Newton, Dalton, Faraday, to mention a few–but not the way I’ve idolized and drenched myself in the works and lives of writers like Keats. And a number of visimagists like Cezanne and Klee. But no composers. I guess the reason for this is obvious: I’ve become a writer, and (to a degree) a visimagist, but not a composer. I consider myself a verosopher, but one unlike any I’m familiar with, except–possibly–Pierce.

It may be that I’ve had no cultural heroes since my thirties due to some flaw of mine, but I suspect one grows . . . not beyond, but off to the sides, of hero-worship. Into too much of one’s own work toward becoming a cultural hero oneself to have as much time new ones. One also will eventually have a number of contemporaries to take the place of heroes, albeit differently–as co-heroes rather than as worship-worthies.

In any case, in my chapter about Keats, I spent over four pages on his sonnet to Chapman’s Homer, which was one of the few poems I’d memorized by then (around the age of 18)–and, for that matter, one of the few I have ever memorized. I wish I’d memorized many more, but I also wish I knew more than one language. I tend to think I’ve stored all the data I’ve been capable of (as has everyone), so it doesn’t bother me inordinately. Just a little wishfulness that a few things were not impossible. Except when I’m in my null zone and realize that nothing really good is possible.

I only memorized one other poem by Keats (also at around the age of 18):

When I have fears that I may cease to be Before my pen hath glean'd my teeming brain, Before high-piled books, in charactry, Hold like rich garners the full-ripen'd grain; When I behold upon the night's starr'd face, Hugh cloudy symbols of a high romance, And think that I may never live to trace Their shadows, with the magic hand of chance; And when I fear, fair creature of an hour, That I may never look upon thee more, Never have relish in the faery power Of unreflecting love!--then on the shore Of this wide world I stand alone and think Till Love and Fame to nothingness do sink.

Note Keats’s glorification of “high-piled books” here and another poet’s accomplishment in the Chapman poem–his raw young poetic ambitions as a young man obvious, so just the thing to capture me at 18–besides the level of the writing. Although poetry was never at the center of my writing ambitions until the past decade or so, by default.

(Aside: after going through my edition of Keats’s poems to make sure I remember the poem above correctly–actually to fix parts I knew I hadn’t–the level of his writing bothered me: in less than 26 years he composed more effective poems than I have in almost 75. This is not false humility. But I feel I have added to the poet’s tool-kit, which he did not, and ranged beyond poetry into a theory pf psychology, which he did not, and which I think beyond doubt an accomplishment of sorts. Yes, competitiveness is an enduring part of my character. I still consider more a virtue than not.)

Okay, back to my dictum about reading poetry to the extent that you devour everything you can of the life and work of at least one of them as I devoured Keats. This resulted in several (but not a flood) of defective poems until I wrote the following in my twenties:

I yearn to run madly into the brush till a wild complexity of chance-created life has cut me off from mortals' petty strife I long to be where swift winds fill with the joyful fundamental music of woods & a gloriously unsymmetrified uproar of grass and violets and weeds and rocks covers every open field and curving hill. I long to stand at the sweet dense core of nature studying the clouds' slow schemes till the regulated world has blurred into nothingness & I am in leagues with dreams..

This is a fair derivative poem, I now think, but indicative only that when I wrote it, I had reached the basement of the poet’s vocation–thanks to all the reading I did. I’m afraid I have to admit that this lesson of mine isn’t much of a lesson, for if you need someone urging you to read poems and writings about poets before you’ll do it, all the reading you do will be a waste of time for you. I did the reading I did because I had to. and I had made a hero of Keats I had to find out as much as possible about, because of my genes, which made me search for a hero, then in effect become a sort of apprentice of his. The real lesson is that you should save time by dropping the idea of becoming a poet if you aren’t already automatically doing this. I suppose a minor implicit value of the lesson is to confirm you in your vocation if you have found your Keats–and encourage you to keep going if you have not, but are deeply involved with some kind of poetry.

.

Entry 1752 — Break-Time

Saturday, March 14th, 2015

I was hoping to continue my lesson with an entry as good as I feel my one yesterday (mostly) was, but got involved in a duel of interpretations of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 24 with Paul Crowley at HLAS. I still was planning to come here and work up a storm but Shirley took care of that. Just as I finished my post for Paul and was about to cut&paste a copy of it in the flash drive I use for things like it, she hopped up on my computer desk, casually walked across my keyboard, then hit the floor again and walked out of the room. In the process, she deleted everything in my post. So I have to do it all over again. I need to because I feel I said a few good things about the poem–and several important things about my discussion of it, which I first called an “explication” but which was not quite that, but–I eventually concluded–the beginning of what I call a “pluraphrase,” and now to make for the poem. So maybe Shirley helped me.

As for the lesson under way, I found the poem of mine that I thought, and am still pretty sure, was the first poem I wrote that, as I put it in Of Manywhere-at-Once, I thought anything of:

I yearn to run madly into the brush till a wild complexity of chance-created life has cut me off from mortals' petty strife I long to be where swift winds fill with the joyful fundamental music of woods & a gloriously unsymmetrified uproar of grass and violets and weeds and rocks covers every open field and curving hill. I long to stand at the sweet dense core of nature studying the clouds' slow schemes till the regulated world has blurred into nothingness & I am in leagues with dreams.

* * *

The “nothingness” is from the sonnet by Keats that ends, “. . . then on the shore/ of the wide world I stand alone and think/ Till Love and Fame to nothingness do sink.” To make sure my lesson has a good poem in its entirety in it, I will quote the Keats poem in full in it. He’s been dead long enough for the imbecilic copyright laws to allow me to do that.

One other thing I have to report is that I came up with a term for “haiku-sensitivity,” which has come to seem too specific for what I want a term to represent. “Minificance,” (mih NIH fih kehnts) is the new term–to represent “a sensitivity to something in poetry of minimlistic significance.” “Haiku-sensitivity” would be a subset of this.

.

Entry 1751 — Lesson 1

Friday, March 13th, 2015

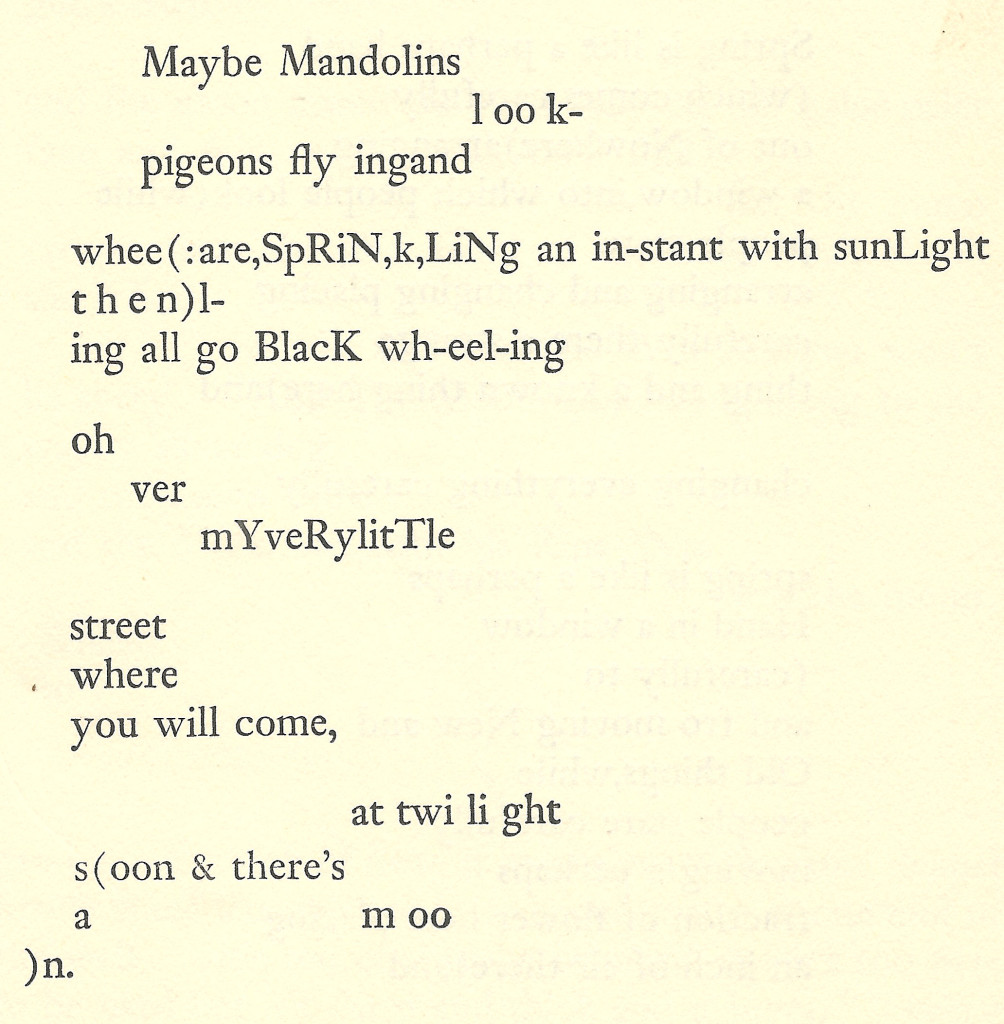

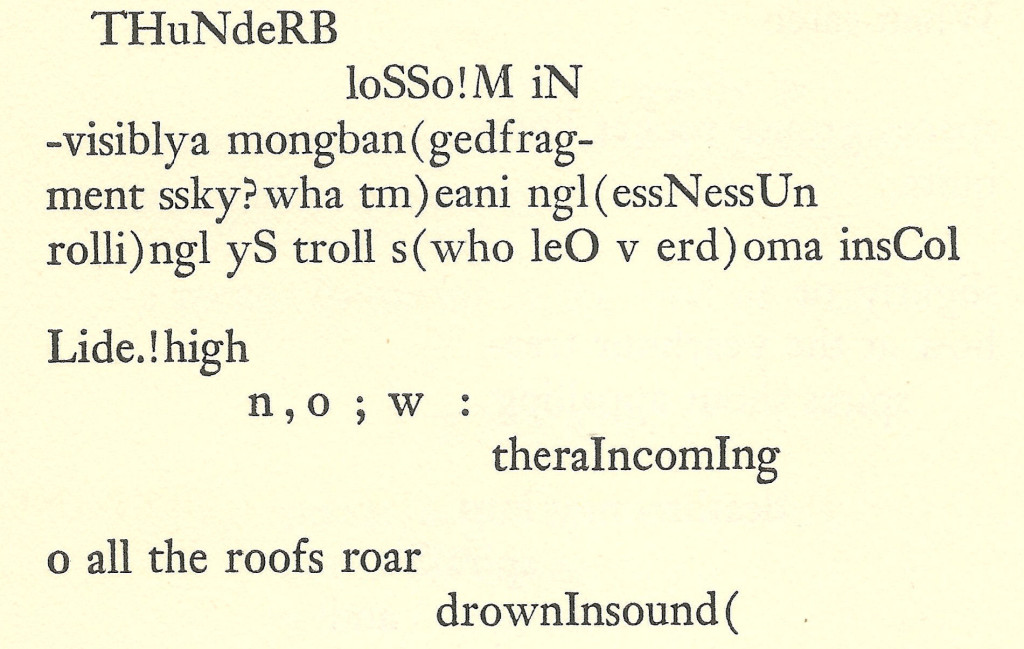

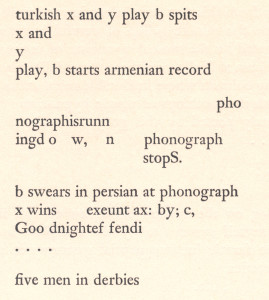

I have an excuse to avoid truly beginning my lesson in how to compose an otherstream poem: another medical procedure, this one a sound scan of my thyroid. Routine, I guess because I’m hypo-thyroidal. Only took ten minutes. Errands followed. So, I’m barely unnull. Nonetheless, I will try to get my lesson in today, beginning with lead-in excerpts of poems by Cummings, then the original (and now final) version of my (full) ooem:

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

If I were in a high school or college teaching this lesson (which, nota bene, is for absolute beginners, although I hope anyone reading it will learn from it), I would pass out hand-outs with the poems above on them to the students (student?). Then:

IF YOU WANT TO COMPOSE ANY KIND OF POETRY:

Dictum 1: READ POETRY!!!

(I’m tempted to end my first lesson there, but–heck–you’re all my good friends! I can’t cheat you.)

Listening to poetry is okay, but reading it means you have it continuingly in front of you, so seems to me better. It’s also difficult to attend readings or buy recordings compared to getting books or magazines with it, or going online after it. In any case, I will be referring to printed poetry only.

I suspect anyone teaching a how-to-course in any kind of literature will tell you the same thing. That doesn’t mean it’s wrong. In fact, it’s received wisdom, and received wisdom is right much more often than not. This bit of received wisdom is maxolutely valid–i.e., it could not be more valid.

The more you read poetry, the more of an idea of what it is you will get. Beyond some dictionary’s probably inept, and certainly incomplete definition of it. But by far the most important reason for reading poetry is to find poems you like! And you will find a few before long, even if you read only publications recommended by college professors or other authorities if you seriously intend to compose poetry–as either a hobby (and there’s nothing wrong with that) or a vocation.

If you get through a few hundred poems and find none that genuinely excite you, ask someone who’s been around (like me) where to go for poetry different from what you’ve been reading. If that doesn’t help–if, that is, you sincerely explore a reasonable wide variety of poems and are not excited by any of them, accept that you’re simply incapable of appreciating poetry–as I am incapable of appreciating gymnastics. So what.

I should think anyone who knows enough about poetry to want to compose it will find poems that he really likes. When this happens, as common sense would indicate, he must find out who wrote them, and look up that poet’s other poems. If this goes well, he will automatically be strongly attracted to one or more, enough to become at least temporarily addicted to his work.

SubDictum 1: When you have found a poet whose work you are extremely drawn to, read everything you can about his life. If you feel like it. I add that, and make this rule a “SubDictum,” because I followed it with great enjoyment and, I think, got a useful push from my vicarious identification with various literary heroes of mine. But it won’t make a poet of you, and I suspect there are those without my interest in poets rather than their work, or literary history. In short, ignore this SubDictum if you have little urge to follow it.

Dictum 2: This is my first teaching that a lot of poets and not all that few teachers of poetry will reject. In fact, I would agree that it is not necessary for one wanting to become a poet; however, it is necessary, in my opinion, for one who wants to become among the best poets. Those I therefore direct to read as much commentary on the poets whose works you most enjoy as you can. Poetry criticism be Good! So what if much of it, maybe most of it, is not too good; 90% of poetry is mediocre or lousy, too. So read as much as you can, and zero in on those whose commentary you enjoy the way you zeroed in on poets whose poems you enjoyed.

One important thing they should do for you is path you to other poets writing work like the ones you like do. Negatively-Positively, they may expose you to flaws in a favorite of yours that helps you to appreciate up to a higher level of enjoyment. They should introduce you, in their negative commentary, to poets whose poor work will increase your appreciation of inferior work, which it is important to learn. Or perhaps make you realize there’s poetry out there the critic doesn’t like but you do. And you will begin developing a critical view of your own.

Dictum 3: WRITE POEMS!!!

Start by imitating the poems you’ve found you like. Remember that you are just beginning and that it takes time to become anything of a poet. In the meantime, it should not take too long for you to experience the happiness of effectively imitating something a hero of yours has done. The chances are 999 to 1 that it will be part of a sub-mediocre poem, but that’s of no consequence. Every poet’s first attempts are poor. Regardless of the mothers or friends or teachers who praise them.

At this point I was going to show the value of imitation using the four texts above. While writing my way to here, however, I realized that I should have used an earlier example of my own work. I wrote a fair amount of bad imitative poetry when I began, and nothing any good until I was around 25 and wrote my “traffic” poem above. It’s a bad example, though, because (in my opinion) quite good, although imitative. There are special reasons for its success. One is that it’s based on the simplest poetic form, the Classical American haiku form (which is derived from the form the Japanese invented–apparently–but significantly different from that in ways I won’t go into right now). What’s more, the Classical American Haiku form is extremely explicit, and therefore easy to get technically right.

* * *

I feel I could keep going for at least a few more full paragraphs but I also think I’ve reached a good stopping point, and have a topic to discuss which may take a while to get through: haiku-sensitivity, which I think a person is either born with or will never have, and I have it. Urp.

.

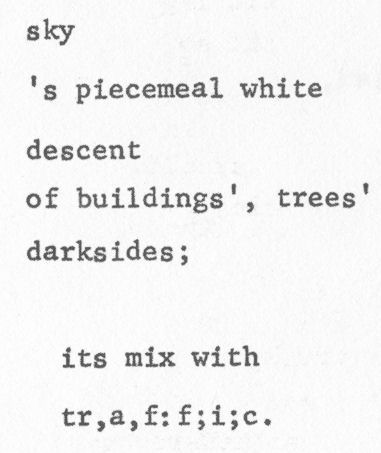

Entry 1750 — Found Original

Thursday, March 12th, 2015

Sorta interesting story about the above: it turned up yesterday in an email from Germany! Remember, I was hunting all over for it in vain, then remembered it together–I thought. Actually, I remembered “descent,” but changed it to “development.” I forgot “mix.” I think the original better than my revision.

Sorta interesting story about the above: it turned up yesterday in an email from Germany! Remember, I was hunting all over for it in vain, then remembered it together–I thought. Actually, I remembered “descent,” but changed it to “development.” I forgot “mix.” I think the original better than my revision.

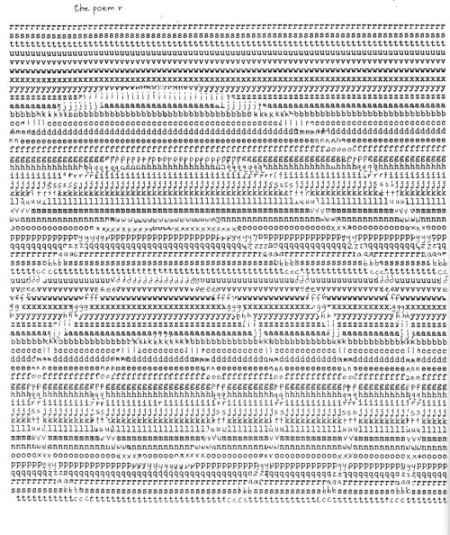

To get back to the sorta interesting story, the email it arrived in–more accurately, the email that had a link to it–was from Kurt Henzel, a German who has suddenly discovered concrete poetry, and wanted to buy two books by Irving Weiss that I had published–and stuff of mine. In his email, he asked for signed copies of two of my poems, the one above and “the poem r,” one of my favorite visual poems although never before mentioned by anyone.

Here’s the other:

Here’s something else from the Internet:

Here’s something else from the Internet:

resipiscence /res-ə-PIS-əns/. noun. Originally, repentance and recognition of one’s misdeeds. Now the act of coming to one’s senses, a change of heart. The Shorter OED’s formulation: “return to a better mind.” From Latin resipiscere (to recover one’s senses), from from sapere (to taste, to be wise).

From yesterday’s Katex–click here to find out about it. (It’s a newsletter or the equivalent put out by Chris Lott often has interesting odd words. I posted this because it seems so much like many of my coinages–in other words, I’m not alone in my love of coining mouthfuls. I also think I might find a use for this one.

* * *

Apologies, but that’s it for today. Again, a tough day for me: a loss in tennis in the morning, both for me and my partner is one match, and for our team in all three of our matches. Oh, well, we should not finish last, and the season will soon be over. In the afternoon, two hours at my dentist’s (that increased my credit card debt by another thousand).

.

Entry 1749 — Lesson One Begins

Wednesday, March 11th, 2015

I was hoping to make a complete lesson for this entry–the one I discussed yesterday for a how-to book for beginning otherstream poets. I had so much trouble scanning the poems by Cummings I wanted to use in it that I’m too worn-out to try to write much of the lesson.

But here is my piece for the lesson again, followed by 4 excerpts of poems by Cummings that I stole the core-technique my poem depends on from Cummings, my lesson being about the necessity to steal from other poets:

sky's piecemeal white development down buildings' dark sides into tr;af:fi,c.

* * *

* * *

* * *

.

Entry 1748 — A Different How-To Book

Tuesday, March 10th, 2015

While writing yesterday’s entry, I thought–as I often do–that I was giving a lesson, for writing about poetry often brings out a need in me to teach others to be able to appreciate, and thus enjoy, the poetry I write about as much as I do. Again today I thought about that while adding another passage to my notes of yesterday. Then it occurred to me that so far as I knew, no one had written a how-to book for beginning otherstream poets. Maybe I should. At worst, it would give me lessons that would take care of my daily blog entries.

I had another tough day, though, and wasn’t up to throwing together a lesson. One reason for the toughness of the day was that I’d come up with a good idea for my first lesson: the use of one of my own early poems as an example . . . but could not find the poem! I still don’t know where I hid it. But I eventually managed to remember how, or about how, it went, so I’ll be able to at least post that here:

sky's piecemeal white development down buildings' dark sides into tr;af:fi,c.

.

Entry 1648 — The Social Role of Poetry

Monday, December 1st, 2014

Today at NowPoetry, a message appeared with a link to two mediocrities writing about

The Social Role of Poetry Since Shelley

While thinking about the question of social roles of vocations, I chuckled to think that I’ve never read anyone writing about the social role of pure mathematics. Surely not even the worst utilitarians would propose that it had one. But then I began to wonder if maybe it did, by adding a different kind of beauty to existence’s than the arts do. Pure mathe-matics at its best is a silent music. It’s a kind of minimalist music, music reduced not just to asensuality, but to something entirely cerebral.

A similar question that it’s amused me to ask at times is what the aesthetic role of politics is. Why shouldn’t it be required to have one by the kind of people who require poetry to have a social function?

.