Archive for the ‘Poetry Criticism’ Category

Entry 1645 — Part of Something from 1994

Friday, November 28th, 2014

I was going to write something new for today but it fell apart somewhere before its midpoint. I have hopes for it, but . . .

So, in place of it, here’s commentary on poetry from an article published twenty years ago that I actually got paid for: 9 pages on all the neglected kinds of poetry then extant (just about all of which are still extant, and neglected). As is the case with nearly all my poetry commentary/criticism, no one every wrote me about it.

I was going to use just what I said about Kathy Ernst’s “Philosophy,” then thought it might be interesting to present the whole page in media res. Less work for me, at any rate. So, here is page 6 from the November/ December issue of Teachers & Writers:

Entry 1453 — One of My Best SPR Columns

Tuesday, August 19th, 2014

When Marilyn emailed me about the publishworthiness of her bookwork, she mentioned that I had reviewed the page I reproduced here yesterday in an old Small Press Review column. Wondering what I’d said, I looked it up (it’s in this blog’s “Pages” to the right), and like it well enough to post it here.

A New Vizlature AnthologySmall Press Review, Volume 29, Number 2, February 1997 Visuelle Poesie aus den USA, edited by Hartmut Andryczuk. 67 pp; 1995; Pa; Hartmut Andryczuk, Postlagernd D-12154, Berlin, Germany Toward the end of 1995 a new anthology of vizlature, or verbo-visual art, came out of Germany. It was edited by Hartmut Andryczuk. I was sent a copy of it because I have a couple of pieces in it, but–alas–I got no details concerning its price. Among the sixteen participants in Andryczuk’s anthology is Marilyn R. Rosenberg, quietly one of this country’s premiere vizlateurs for some two decades. She is represented by a landscape-sketch close enough to an outline to double as a map, thus exploiting the tension of the literal versus the abstract. Her piece is all in calligraphic lines of various degrees of thickness and delicacy that delineate clouds (or mountains) forming above water foaming into being among juts of a landmass. The latter includes an area that could be either a tilled field or a lined page, but in either case is a locus of creativity. At various points in the composition are a Q, and an A (to suggest question/answer), three X’s, a C and a T–and, right together, a W, an upside-down W (or M), and a sideways W (or E), to put us in a Japanese-serene country where a breeze can tilt West to East, and all hovers mystically just short of nameability. In dramatically unbreezeful contrast to Rosenberg’s piece is John Byrum’s “Transnon,” which consists, simply, of “TRA/ NS/ NON” in large white conventional letters against a black background. With the two cardinal directions missing in Rosenberg’s composition (north and south) in it, and black & white . . . and a backwards rendering of the word, “art,” this work seems almost monumentally engaged with ultimate dichotomies. Two more map/drawing/poems are presented by Richard Kostelanetz, from an early work of his using text-blocks of pertinent city impressions (e.g., “Boutiques,/ mostly in/ basements,/ their names/ as striking/ and transient/ as rockgroups:/ ‘Instant Pants’/ ‘Pomegranate’ . . .”) to represent various blocks of New York such as that defined by First and Second Avenues and St. Mark’s Place. Very local-feeling, intimate, accurate. A similar kind of opposition is at the heart of one of Nico Vassilakis’s contributions to this volume, “foremmett” (“emmett” being famous visual poet, Emmett Williams). It consists of a square with two parallel lines drawn horizontally across it near its middle; just above the upper line is “BL”; just below the lower line is “RED”; in between them is “UR.” In the corners of the upper section of the diagram the word, “blue,” is repeated; the word, “red,” is repeated in the corners of the lower section, while “purple” is printed once at each end of the narrow middle section. Another minimalist, almost overlookable piece that teems with the blur of science and sensuality, or where blue analysis becomes, or arises from, a red mood. . . . Three poems by Dick Higgins carry on this kind of letterplay in homage to Jean Dupuy, ina blom and wolf vostell. The first, just four lines in length, demonstrates the technique: “JEAN DUPUY/ NUDE JAY UP/ DUNE JAY UP/ PUN JAY DUE.” Then, following a charming mathematico-visual tribute to his daughter Amy, Karl Kempton does a lyrical take on the moon that includes a partial reflection of the moon as “wo u,” to magically suggest a fragment of “would,” or moon-distant wishfulness. Chuck Welch, active in mail art since 1978 as “the Crackerjack Kid,” contributes a moving swirl of words enacting Gaea’s flow which ends with “this dream truss/ clerestory/ Gaea’s blueprint,” but also a medallion-sort of visual poem that I liked less well: it looks nice but too boiler-platedly condemns white C(IA)olonialism and genocide, for my taste. A “cubistic” specimen of Gregory Vincent St. Thomasino’s Go series is here, too, with a more clearly visual poem from the same series that evokes a rescue at sea, a flare filling the sky with o’s while the excitement of the situation fills it with oh’s. St. Thomasino, and many of the other artists in the volume, provide readers with a short artist’s statement, by the way, which are quite useful. Others with first-rate pieces in this volume are M. B. Corbett, Harriet Bart, Harry Burrus, Spencer Selby, Stephen-Paul Martin, John M. Bennett (who does terrific things with near-empty frames of the tackily rubber-stamped kind well-known to those familiar with his work) and Paul Weidenhoff. All in all, Andryczuk’s anthology gives a valuable if rough idea of the terrain of current American vizlature. |

* * * * *

How I wish someone would tell me (in reasonable detail) why in the sixteen years since then, no one in the BigWorld has ever asked me for a piece like it?! Is it that inferior to the poetry-related pieces in magazines like the Atlantic? Or too different? Maybe too clearly politically-incorrect? Or is it that there is absolutely no one on the look-out for fresh talent? I have little to add to what I said in my column about Marilyn’s piece except that my first impression on seeing it again was that it seemed to me strongly Chinese (which I mean as a Large Compliment) and I again felt enlarged by its Q&A, this time by the ocean seeming to query the land . . . which provided, or was the answer. I was influenced a lot about some of Marton Koppany’s Q&A-related pieces that I’ve recently been enjoying and writing about.

Note: I corrected a typo or two in my column but left some of my now-obsolete terminology as is.

.

Entry 1308 — Mine Review Continueth

Monday, December 23rd, 2013

I was going to celebrate the Winter Solstice with Zero Production, but then I found out yesterday, not today, was when it occurred, so I had to finish the review I was working on. I wrote over 1300 word, pretty good ones, I think. Below is one of the poems I dealt with, with my comments on it following it:

Something of what seems to me at the frontier of math-related poetry that I hope will be further explored in the future is Sarah Glaz’s fascinatingly strange “13 January 2009.” It consists of two texts side by side, one, “13,” with nothing in it but numbers (and equal signs), the other, “January 2009) devoted entirely to words about the dying of a man named Anuk whom I take to be an ancient Egyptian (in spite of the poem’s title!) I feel ready to go on for another thousand words at least about this poem, but will limit myself here to telling you that, according to its author, its “structure follows The Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic, which states that every positive integer greater than one may be expressed in a unique way as a product of powers of distinct prime numbers”—which (inexorable) process, I would add, is shown in “13.” I hope to say more in an essay on mathematical poetry I have in the works for this periodical. Conclusion: when I began thinking about this review, I had visions of making an insightful taxonomical study of its poems, but their “multi-dimensional links to mathematics and . . . wide range of styles” as Glaz has it in her introduction, and wide range of techniques, I’d add, made that too difficult a task. So all I have to say now is that I hope anyone still reading this has enjoyed my chatter as much as I’ve enjoyed indulging in it.

.

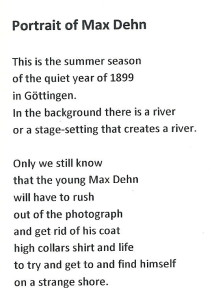

Entry 1307 — “Portrait of Max Dehn”

Sunday, December 22nd, 2013

Below is a poem from an anthology I’m writing a review of.

It’s by Francisco Jose Craveiro de Carvalho as translated from the Portuguese by Manual Portela. All it tells us (with a nice touch of surrealistic fantasy) is that Dehn was an emigrant–but it does so with the same kind of inspired empathy with which Keats famously described Ruth, amidst the alien corn. It’s here because I like it, but more because I wanted to say something about the Reviewer’s Delight I felt when, in writing about it, I saw my way to giving a poet what I feel is a high (and appropriate) compliment while also again praising my old favorite, Keats. Such delights are what make reviewing worth doing no matter how difficult it is at times.

.

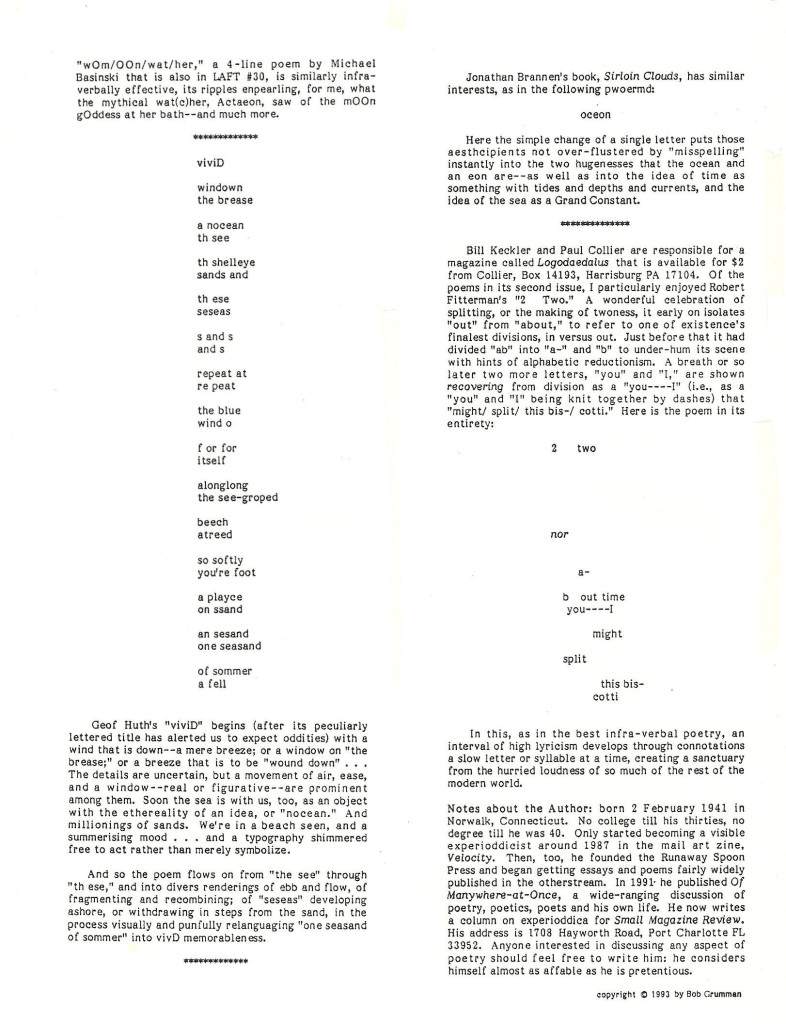

Entry 1207 — The Experioddicist, July 1993, P.4

Sunday, September 8th, 2013

Note: I consider Geof’s poem a masterpiece–one of more than a few he’s done I wish I’d done.

.

Entry 1206 — The Experioddicist, July 1993, P.3

Saturday, September 7th, 2013

Sorry–once again your imbecile of a blogmaster forgot to hit the button changing this from a withheld entry to a public one. Here it is two days late:

.

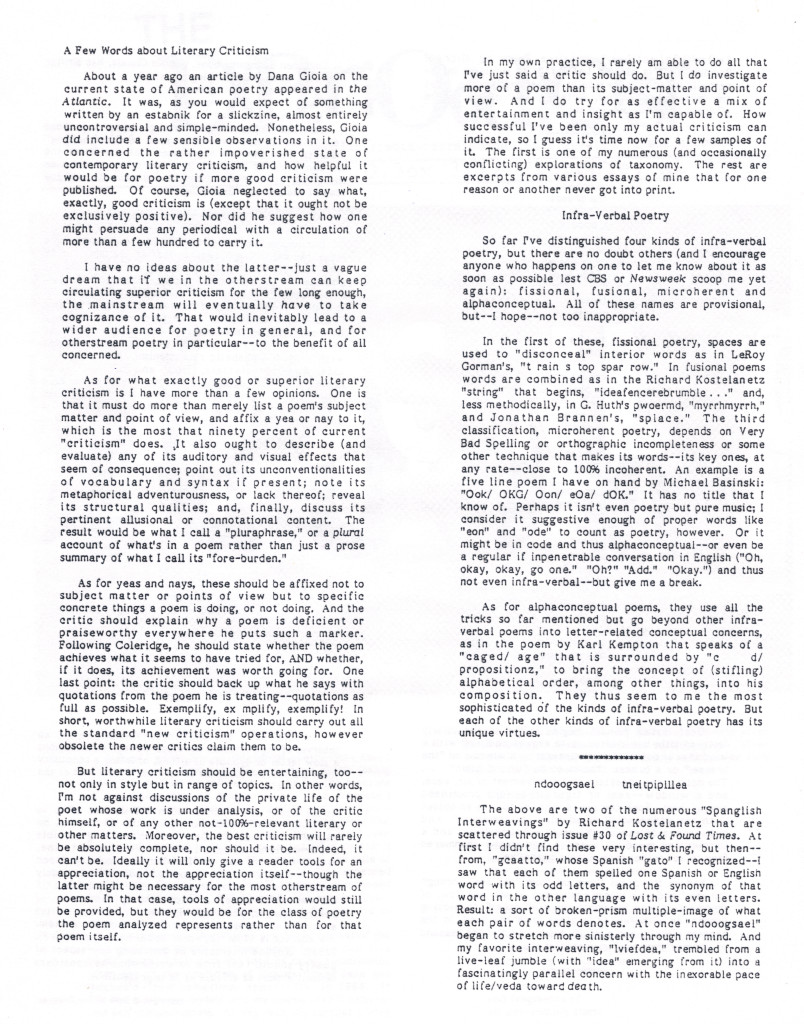

Entry 803 — Insulting BigName Critics

Wednesday, July 18th, 2012

After Finnegan, sitemaster of New-Poetry, let New-Poetry members know that we could find essays by various critics commenting on the current state of American Poetry at the VQR Symposium yesterday, I visited the site, read some, skimmed some, then posted the following at New-Poetry:

Thanks much for this, Finnegan. All these critics and Perloff (whom I count as part of the VQR Symposium group although she withdrew from it because she has remained an important part of it, anyway) is the only one who mentions visual and performance poetry, and all she does is mention them. The most visible two poetries of the Otherstream. But that’s enough to keep me from judging her thoughts on the contem-porary poetry scene the worst in this collection. The others are too closely worthless to pick out one for worst effort.

I will admit one thing not too hard to admit: a few of these estabniks seem somewhat familiar with what they deem a new sort of poetry—conceptual poetry—a kind of poetry, if it’s poetry (and Perloff questions whether at least some texts called conceptual poetry are poems) with which I was unfamiliar. But I’ve always said in my lists of new and newish poetry that I was sure I’d missed some, and know I’ve fallen behind badly in keeping up with various kinds of cyber poetry, never felt comfortable with my take on sound poetry, and only now believe I’m coming to terms with language poetry (although I arrogantly also feel I’ve known more about it for twenty years than just about anybody writing it, or writing poetry called language poetry, including especially Ron Silliman).

From the few examples of conceptual poetry I’ve seen, I have what I think is Perloff’s view, that it’s too similar to dada to be new, and—as I said—possibly prose (of a kind I’ve named “conceprature” to go with similar taxonomical terms I’ve used for “poetry” that’s really prose, “evocature” for prose poems, and “advocature” for lineated propaganda texts. I also use “informrature” for lineated texts like names and addresses on envelopes that are clearly not poems). Having said all that, I do believe that conceptual poets-or-prosists (note: “prosists” is an ad hoc term; I want something better, preferably already in use) are cutting edge even though working in a variety of literature that’s been around a long time—because (1) they are still finding significantly new things to do in it (new to me, anyway) the same way I believe a few visual poets are still finding significantly new things to do in visual poetry, which—in its modern phase—has now been around a century, give or take a decade or two, its start being still controversial; and (2) only a very few visible critics know about them, and only one, Perloff, has so far written meaningfully about them.

I should be kinder to Perloff than I have been for the past 25 years, and will be from now on, I’m pretty sure. But nothing is harder for someone fighting against the status quo not to blow up at than another fighting against it differently (usually much less differently than its seems to both at the time).

Below is perhaps the best example of anti-Otherstream gatekeeping in the tripe Finnegan linked to, a passage from Willard Spiegelman’s hilariously-titled essay, “Has Poetry Changed? The View From the Editor’s Desk.” Its title is funny because it contains not one word about how American poetry has changed over the past 30 years or so. (Note, by the way, another change in my boilerplate: “30,” not “50” years as I so long contended. I finally realized that Ashbery and his followers were, when breaking into prominence, using techniques not in wide use at the time–although far from revolutionary.)

“Some years ago Helen Vendler said she was giving up reviewing or generally writing about new books of poetry by younger poets. She had not lost her acumen, her interest or her powers of perception; rather, she said that she lacked the right cultural frame of reference to be an appropriate audience, let alone a judge. She knew about gardens and nightingales, Grecian urns and Christian theology, but not about hip-hop or comic books, and these provide the material, or at least the glue, for many of today’s poems. Poetic subjects, voices, diction, and tone change. And forms, like subjects, change as well. She wanted to leave the critical field open to younger people like her colleague Stephen Burt, a polymath who knows the ancients and the moderns, the classics and the contemporary. He listens to indie bands and reads graphic novels. He flourishes amid the hipsters as well as the sonneteers.” Etc.

Why is this especially stupid, in my view? The idea that the main thing a critic needs to be familiar with to write about poetry is subject matter. Oh, and “voices, diction and tone.” Oops, “forms,” too. No mention of what Vendler has been drastically ignorant of since she was first writing about Ashbery: technique. Perhaps I’m wrong to consider it the most important component of poetry, but it most certainly is as important as “voices, diction and tone.”

Then there is her leaving the field open to people like Stephen Burt. A Harvard professor! And no more knowledgeable than Vendler about what’s going on in poetry now. Here’s one thing Wikipoo calls him recognized as a critic for, his definition of what I call jump-cut poetry (but long ago referred to it a few times as “elliptical”): “Elliptical poets try to manifest a person—who speaks the poem and reflects the poet—while using all the verbal gizmos developed over the last few decades to undermine the coherence of speaking selves.” I like his “all the verbal gizmos.” Does he mention even some of those invented way before his time by Cummings. I don’t know his criticism well enough to be sure the answer is no, but I’d be willing to bet ten bucks it is.

I’d be interested to know why what I’ve written here contributes less to the discussion in VQR of the current state of American Poetry than the essays in it. Anyone interested in telling me? Or even in telling me why I’m not worth telling? I’ve issued challenges like this before. No one’s yet answered one. At least one that doesn’t significantly misrepresent me, and escalate into ad hominem arguments and plain insults.

Note: I’m pretty sure that 15 or 20 years ago, one of the two times I was stupid enough to apply for a Guggenheim grant, Willard Spiegelman got one in the field I’d applied for one in. I can’t remember how he described his winning project except that it was lame, even for a mainstreamer. (Richard Kostelanetz, a former winner of a Guggenheim, had recommended me to the Guggenheimers, who then invited me to submit an application, so it wasn’t all my fault.)

.

Entry 657 — My Motto as a Poetry Critic

Thursday, February 16th, 2012

Thinking about what Tony Robinson had at his blog spurred me to this motto of my own (obnoxious) practice as a poetry critic: Try for maximal understanding of the nature and value of what I’m critiquing, fully committed to the advance of poetry, as I understand it, and expressed with the best balance of clarity and fresh language I can manage. I originally continued with “–with no significant suppression of emotion, regardless of the tender feelings of the hyper-offendable,” but upon reflection found that nice to say but too secondary for this motto.

Better: Using the the best balance of clarity and fresh language I can manage, try to express maximal understanding of the nature and value of what I’m critiquing, fully committed to the advance of poetry, as I see it. Ah, but I now see that “the value of what I’m critiquing” would include what the latter does to advance poetry. Ergo: Try, using the the best balance of clarity and fresh language I can manage, to express maximal understanding of the nature and value of what I’m critiquing.

And here’s a copy (an imperfect one) of my motto as a poet:

.

Entry 583 — The Text of My Triptych

Sunday, December 4th, 2011

(This is a day late but I had it done in time, honest! I just forgot to change the “private” setting to “public.”)

For lack of anything else to post today, which is one of my null days, here’s the text of the poem in the sub-dividend product of the frame from “Triptych for Tom Phillips that was in yesterday’s blog entry:

From is for every bound alled.

Similarly, if is alled. {urthermore}.

This is also the.

+ infinity (actually, the symbol for infinity) in port ever.

This is basically something about the allness of the state of from-ness and if-ness. “Urthermore” has something to do with final origins although right now I can’t think what. So does the the from Stevens that whatever “this” refers to is also. Positive infinity is said to be forever in port. All this is a close representation of “arrival,” needing only the graphic shown as the remainder to exactly represent it. The fore-burden of the text (for me) is that a poem is an arrival. Note, however, that this text has three different direction to turn into a departure into. To begin a consideration of one of my most ambitious and complex works that I will say a little more about, maybe, tomorrow.

* * *

Saturday, 3 December 2011, 5 P.M. Not a great day–the least productive since I started my attempt to be culturally methodical. I post my blog entry for the day, but had it done yesterday. The only thing I did so far as the exhibition is concerned is get my triptych printed at Staples, buy three frames for it, and frame one of the two sets I have. It does look nice. But I think I see how I can make another triptych that’s much better.

I also played tennis.

.

Entry 581 — My Most-Used Quotient

Friday, December 2nd, 2011

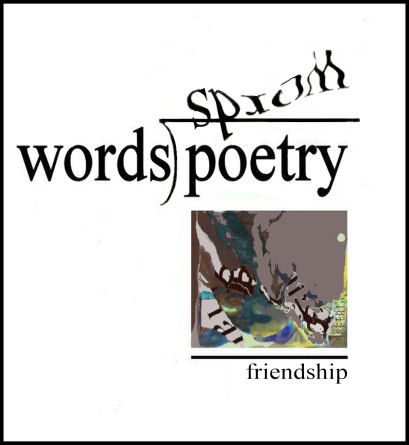

This is the quotient in just about all my twenty or more long divisions of “poetry.” It’s intended to convey the meaning of Dickinson’s lines about telling the truth, but telling it “slant,” so represents “superior poetic diction.” That’s all I took it for, for a long time. I was disturbed, however, that, as a general term that in my division of poetry, almost always multiplies another general term, like “words,” it should yield a general product, not the specific product I always had it yielding. Take the first division in the series:

My problem with this and the others would possibly never occur to anyone but me, but it bothered me for years: how could I say that slant-words times words (or whatever) should equal the very idiosyncratic graphic the long division claims it does. Just now, I thought of my way out. It was to recognize the image of the slant-words as one of an infinite number of such words! Big thrill, hunh. Well, to me it meant that there was nothing wrong with having this one instance of poetic diction multiplied by words (in-general) equal the particular instance of–not poetry, but of something almost poetry that needs “friendship” to make it poetry. (That latter, folks, is an attack on hermetic poetry–if no one gets anything out of your poetry but you, it’s not poetry, even though that may be the case with my poetry.)

If nothing else, you have now been exposed to the kind of nutty need I have to make my mathematical poems mathematically valid, at least in my own mind.(Note: the poem I have posted here is different from both what it was originally and what it was in its last published version. I think I have it in its final form now, though. I changed the graphic five or more times because it kept seeming to me that a goose was in it, and I didn’t want no goose in it!

* * *

Thursday, 1 December 2011 Not much to report. I attended a match my tennis team played, and won, 3-0. I was the back-up for this one. Very cold (for Florida). After I got home, I ran again, this time completing a mile. I went very slowly, finishing with a time about eleven-and-a-half minutes. I really do think I’ll be able to improve on that. I worked on “Frame No. 7″ of my long division of poetry series and put an black&white illustration of it on an exhibition hand-out but forgot to write a commentary on it. I did get this blog entry wholly done, and I consider the work I did on the mathemaku a reasonable day’s work for the exhibition.

.