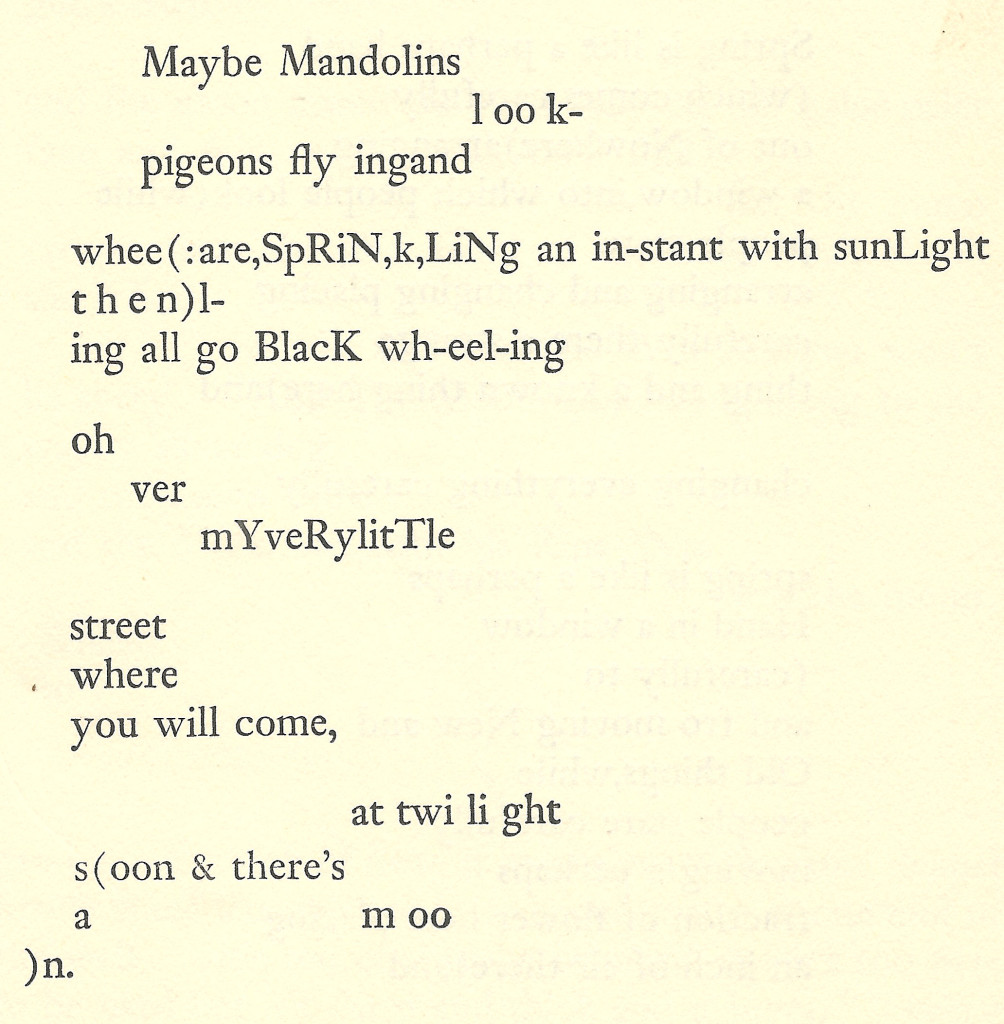

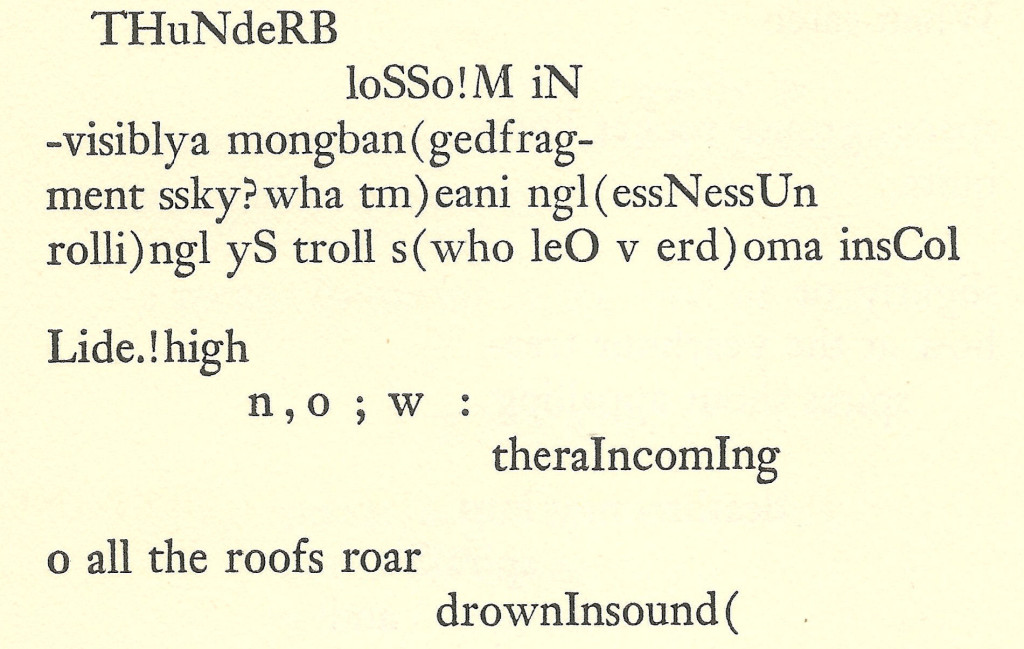

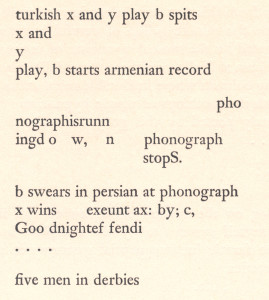

I have an excuse to avoid truly beginning my lesson in how to compose an otherstream poem: another medical procedure, this one a sound scan of my thyroid. Routine, I guess because I’m hypo-thyroidal. Only took ten minutes. Errands followed. So, I’m barely unnull. Nonetheless, I will try to get my lesson in today, beginning with lead-in excerpts of poems by Cummings, then the original (and now final) version of my (full) ooem:

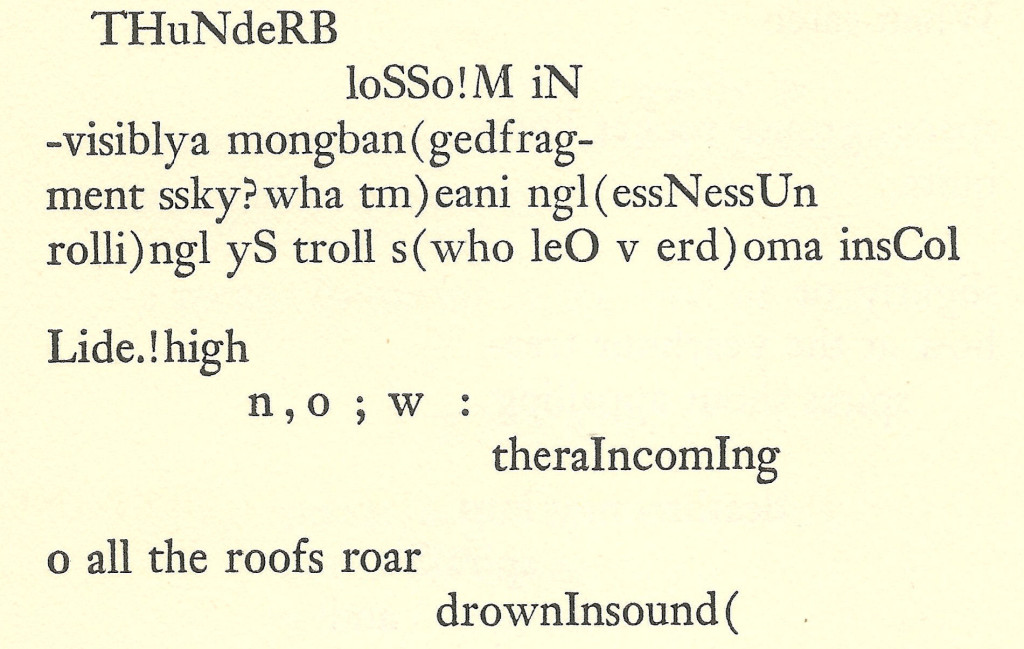

* * *

* * *

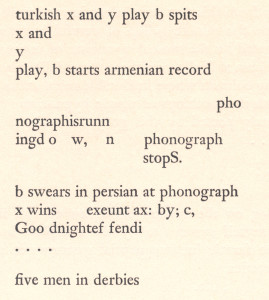

* * *

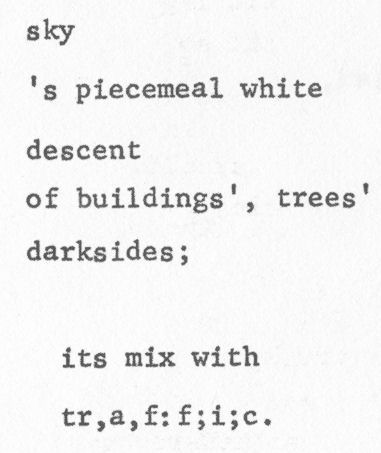

* * *

* * *

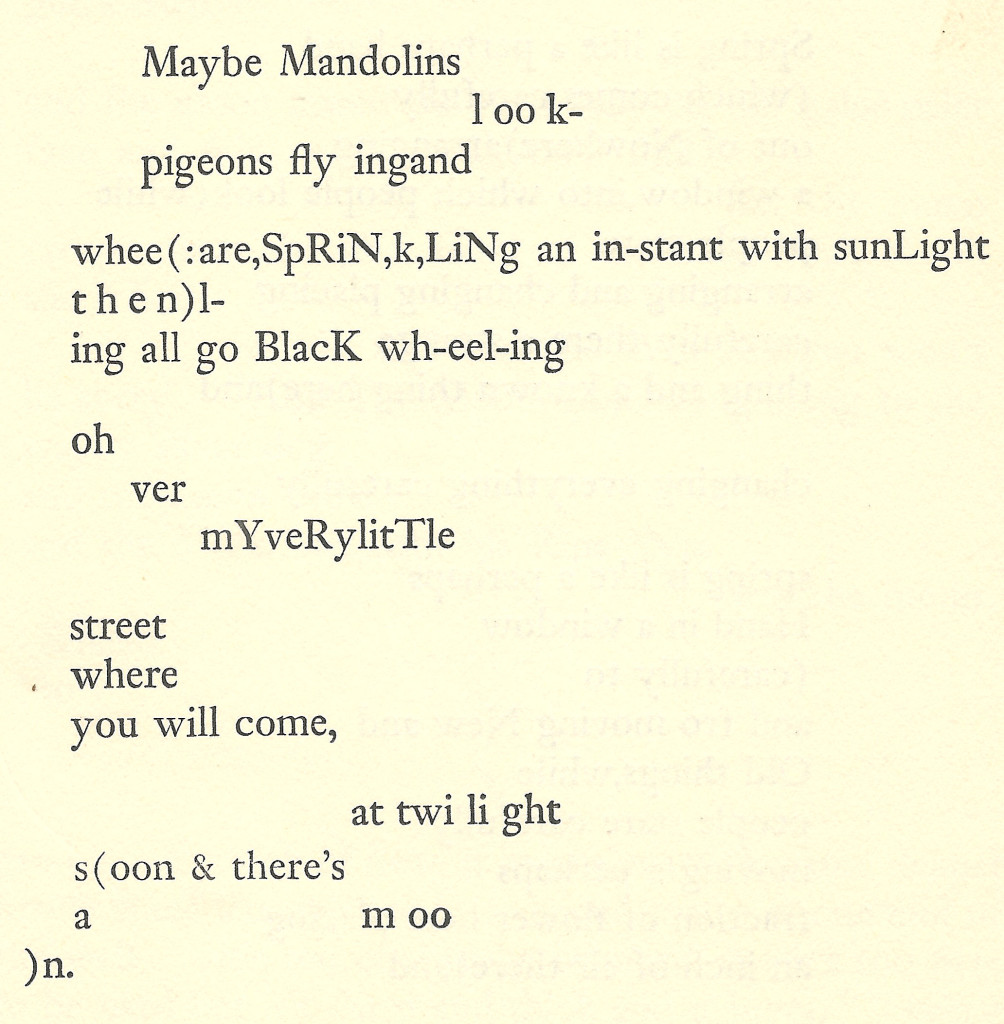

If I were in a high school or college teaching this lesson (which, nota bene, is for absolute beginners, although I hope anyone reading it will learn from it), I would pass out hand-outs with the poems above on them to the students (student?). Then:

IF YOU WANT TO COMPOSE ANY KIND OF POETRY:

Dictum 1: READ POETRY!!!

(I’m tempted to end my first lesson there, but–heck–you’re all my good friends! I can’t cheat you.)

Listening to poetry is okay, but reading it means you have it continuingly in front of you, so seems to me better. It’s also difficult to attend readings or buy recordings compared to getting books or magazines with it, or going online after it. In any case, I will be referring to printed poetry only.

I suspect anyone teaching a how-to-course in any kind of literature will tell you the same thing. That doesn’t mean it’s wrong. In fact, it’s received wisdom, and received wisdom is right much more often than not. This bit of received wisdom is maxolutely valid–i.e., it could not be more valid.

The more you read poetry, the more of an idea of what it is you will get. Beyond some dictionary’s probably inept, and certainly incomplete definition of it. But by far the most important reason for reading poetry is to find poems you like! And you will find a few before long, even if you read only publications recommended by college professors or other authorities if you seriously intend to compose poetry–as either a hobby (and there’s nothing wrong with that) or a vocation.

If you get through a few hundred poems and find none that genuinely excite you, ask someone who’s been around (like me) where to go for poetry different from what you’ve been reading. If that doesn’t help–if, that is, you sincerely explore a reasonable wide variety of poems and are not excited by any of them, accept that you’re simply incapable of appreciating poetry–as I am incapable of appreciating gymnastics. So what.

I should think anyone who knows enough about poetry to want to compose it will find poems that he really likes. When this happens, as common sense would indicate, he must find out who wrote them, and look up that poet’s other poems. If this goes well, he will automatically be strongly attracted to one or more, enough to become at least temporarily addicted to his work.

SubDictum 1: When you have found a poet whose work you are extremely drawn to, read everything you can about his life. If you feel like it. I add that, and make this rule a “SubDictum,” because I followed it with great enjoyment and, I think, got a useful push from my vicarious identification with various literary heroes of mine. But it won’t make a poet of you, and I suspect there are those without my interest in poets rather than their work, or literary history. In short, ignore this SubDictum if you have little urge to follow it.

Dictum 2: This is my first teaching that a lot of poets and not all that few teachers of poetry will reject. In fact, I would agree that it is not necessary for one wanting to become a poet; however, it is necessary, in my opinion, for one who wants to become among the best poets. Those I therefore direct to read as much commentary on the poets whose works you most enjoy as you can. Poetry criticism be Good! So what if much of it, maybe most of it, is not too good; 90% of poetry is mediocre or lousy, too. So read as much as you can, and zero in on those whose commentary you enjoy the way you zeroed in on poets whose poems you enjoyed.

One important thing they should do for you is path you to other poets writing work like the ones you like do. Negatively-Positively, they may expose you to flaws in a favorite of yours that helps you to appreciate up to a higher level of enjoyment. They should introduce you, in their negative commentary, to poets whose poor work will increase your appreciation of inferior work, which it is important to learn. Or perhaps make you realize there’s poetry out there the critic doesn’t like but you do. And you will begin developing a critical view of your own.

Dictum 3: WRITE POEMS!!!

Start by imitating the poems you’ve found you like. Remember that you are just beginning and that it takes time to become anything of a poet. In the meantime, it should not take too long for you to experience the happiness of effectively imitating something a hero of yours has done. The chances are 999 to 1 that it will be part of a sub-mediocre poem, but that’s of no consequence. Every poet’s first attempts are poor. Regardless of the mothers or friends or teachers who praise them.

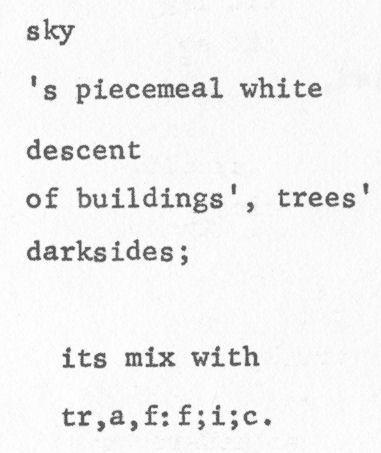

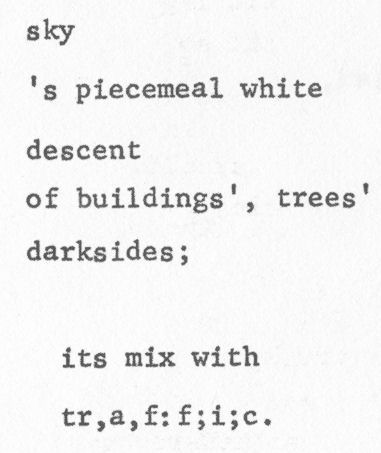

At this point I was going to show the value of imitation using the four texts above. While writing my way to here, however, I realized that I should have used an earlier example of my own work. I wrote a fair amount of bad imitative poetry when I began, and nothing any good until I was around 25 and wrote my “traffic” poem above. It’s a bad example, though, because (in my opinion) quite good, although imitative. There are special reasons for its success. One is that it’s based on the simplest poetic form, the Classical American haiku form (which is derived from the form the Japanese invented–apparently–but significantly different from that in ways I won’t go into right now). What’s more, the Classical American Haiku form is extremely explicit, and therefore easy to get technically right.

* * *

I feel I could keep going for at least a few more full paragraphs but I also think I’ve reached a good stopping point, and have a topic to discuss which may take a while to get through: haiku-sensitivity, which I think a person is either born with or will never have, and I have it. Urp.

.