Archive for the ‘Jason Guriel’ Category

Entry 982 — A Philistine Versus Cummings

Sunday, January 13th, 2013

The following is from Poetry, America’s leading home of Philistines. It’s part of a series of negative responses to canonized poets by mostly utter mediocrities (at best). Guriel, author of this slam of Cummings, seems the most egregious, for the others bothered to find parts of their subject’s oeuvre worth praise, or at least not bad enough to scorn. The author of one, on Stevens, forthrightly admitted not having the brains to appreciate him–although she may have been ironic.

It’s fitting that Cummings took the most abuse, for his best work is still a decade or more too advanced for Poetry.

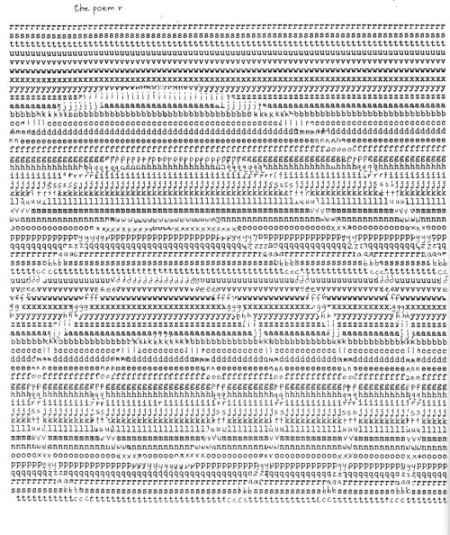

Guriel may not be the most obtuse critic of Cummings ever–while Cummings was still alive, some halfwit whose name I failed to record parodied him by throwing letters on a page “almost as fast as (he) could hit the typewriter keys,” and calling the result, “Forest Fire.” This he follows with a mock “critique” of the poem, praising its “typographically created impression of chaos, suggested by a broken word such as ‘hiss’ and by the skillfully misplaces letters and punctuation marks, all of which add eloquently to the complex simplicity and the dissociated unity of the whole.” Ha ha, aren’t these avant garde critics dumb!

The philistine always assumes a poet he can’t appreciate is only doing one thing in his poetry, so has no problem parodying it since all he has to do is compose something that does nothing but that one thing, as here. He, of course, disregards the fact that doing something another poet has invented is easier than inventing it.

Time now for Guriel, with my commments inserted:

Sub-SeussReconsidering E.E. Cummings.

BY JASON GURIEL

Young people encounter many temptations on their way to adulthood: vampires, Atlas Shrugged, Pink Floyd, the acoustic guitar. Of course, such stuff, designed to indulge one’s sense of oneself as a unique individual, must eventually be repudiated. It’s not easy, growing up.

BG: Growing up requires one to accept that one is a sheep, and leave behind a child’s imaginativeness?

But I had no trouble saying no to the relentlessly quirky E.E. Cummings. Thank the high school teacher who required me to get Cummings’s “anyone lived in a pretty how town” by heart. I labored over the poem for an afternoon, recited it to the wall, gave up. What was at stake if I misremembered the order of words like “up so floating many bells down?” Does it really matter it’s not “up so many floating bells down?” Would Cummings himself have applauded the mistake as a heartening sign of a maverick mind at play?

BG: Yes, Jason, it matters. To understand that, you must first be able to imagine yourself not necessarily superior to a poet doing unconventional things with syntax, but assume that maybe he’s trying to give pleasure by doing so rather than irritate his readers. Here Cummings forces his readers to slow down, the first obligation of a poet, for a poet should want those encountering his work to take the time to let its full sensual effect to reach them. The slight change of word-order is not pivotal, but “so floating many bells” is a more charged image, it seems to me, than “so many floating bells”; the syntax of the first jarring the reader into increasing attention, wondering about “so floating” ( a slant way of saying “so floatingly” to increase the meaning of floating?), and about a “floating many,” the syntax of the second doing nothing. I would add that Cummings uses “up” and “down” simply to describe in a way that almost forces a reader to look up and down bells floating up (and) down. Whatever they are. Bell-sounds and bell-shaped flowers are what they made me think of. They do make one muse into concrete imagery, which is an important duty of poems.

The poetry, I concluded, wasn’t just sub-Seuss; it was tantamount to a teaching tool of the most condescending kind: the last resort. (No, really, poetry is crazy fun was the point one was meant to internalize.) Cummings seemed to have been invented to convert that stubborn student the syllabus has failed to win over to verse — or, at least, to reacquaint the kid with his inner child, the id whose appetite for nonsense and nursery rhymes has been socialized away. When it came to Cummings (or unstructured playtime) resistance was supposed to be futile.

BG: Here Guriel its criticizing Cummings for what he thinks his teacher used his poem for. I haven’t spoken with his teacher. It would be interesting if Poetry contacted the teacher and learned the motive for forcing poor Guriel to memorize a poem he didn’t like. (Guess what? It’s far from my favorite Cummings poem.) It’s good to expose students to the crazy fun that poems can be, including the very best. But the teacher might have been thinking of language poetry, so many of whose best features Cummings’s poems were precursors of, the idea being that immersion in Cummings would help the right students later to appreciate the poetry many superior contemporary poets are composing. There are several other possibilities. I suspect, though, that the teacher simply liked the poem and wanted to give students a chance to like it, too.

Randall Jarrell nearly said as much when he noted that “no one else has ever made avant-garde, experimental poems so attractive both to the general and the special reader.” He should’ve said that “no one else has ever made a formula for avant-garde, experimental poems so attractive to people who don’t actually read poetry but would like to think they can write it.” Even today, it’s enough to reject an institution or two — capitalism, grammatical English — to be mistaken for an innovator. Rebel, misspell, repeat:

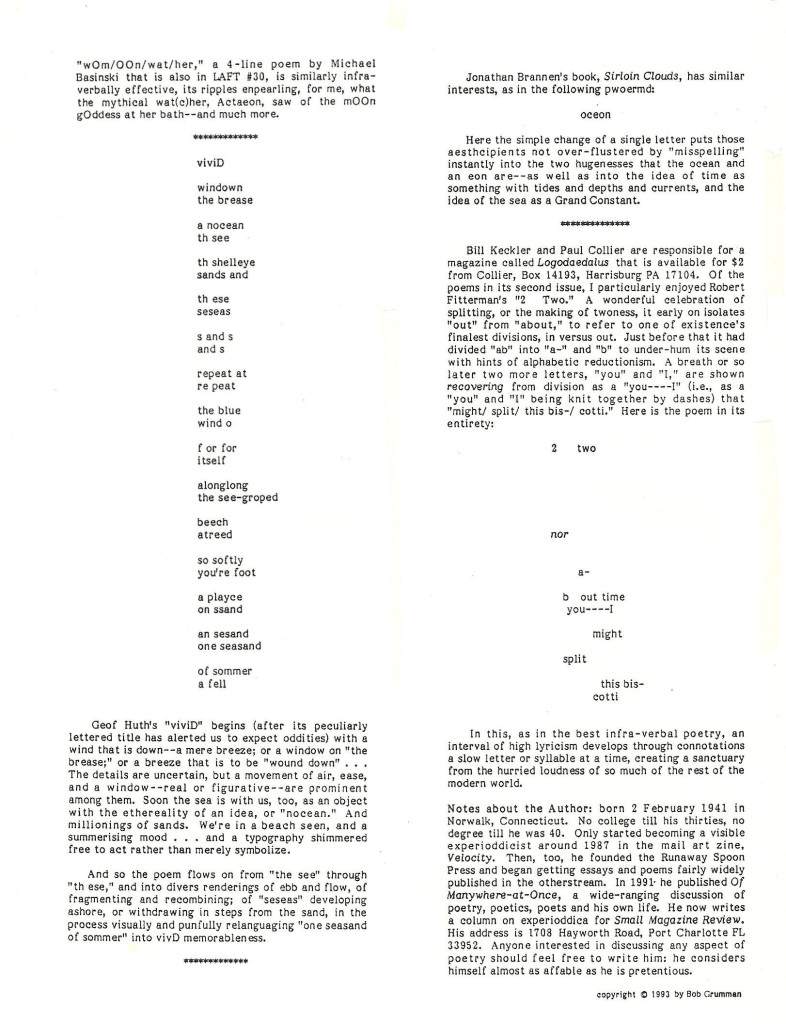

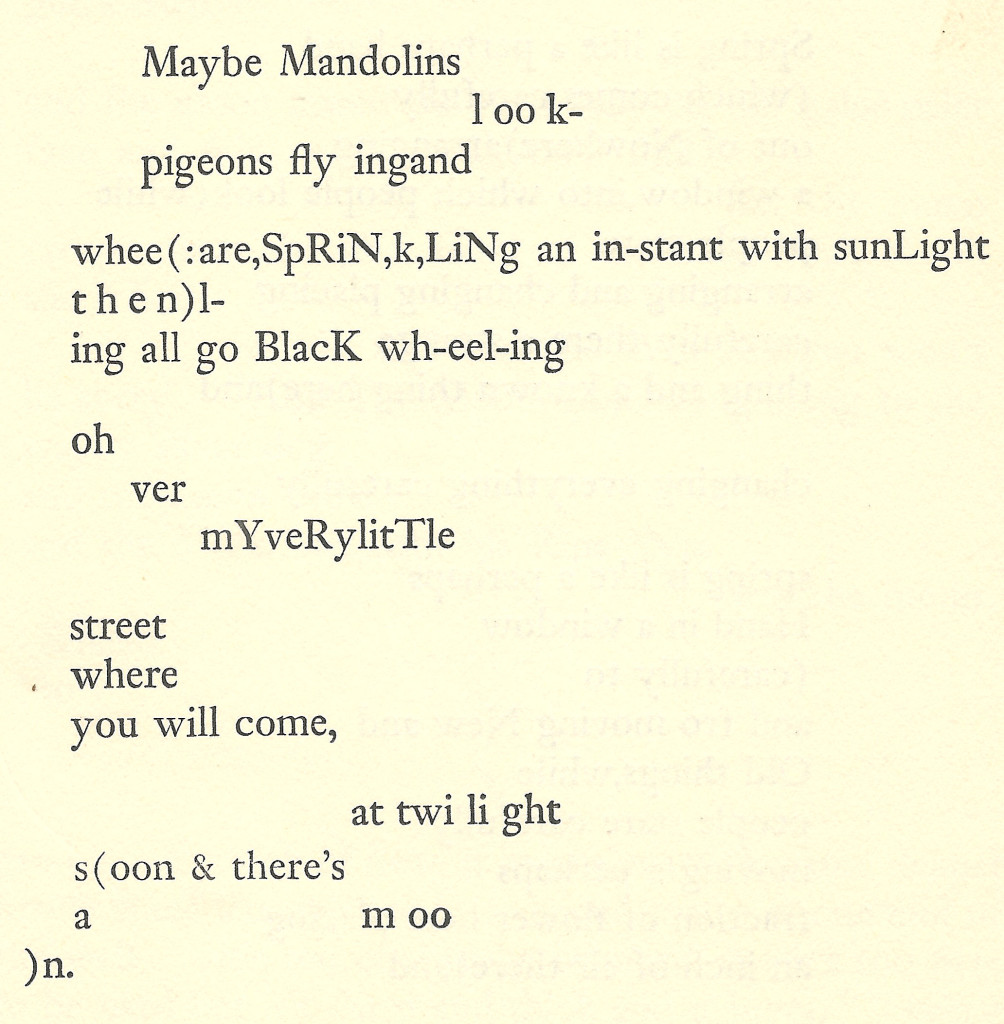

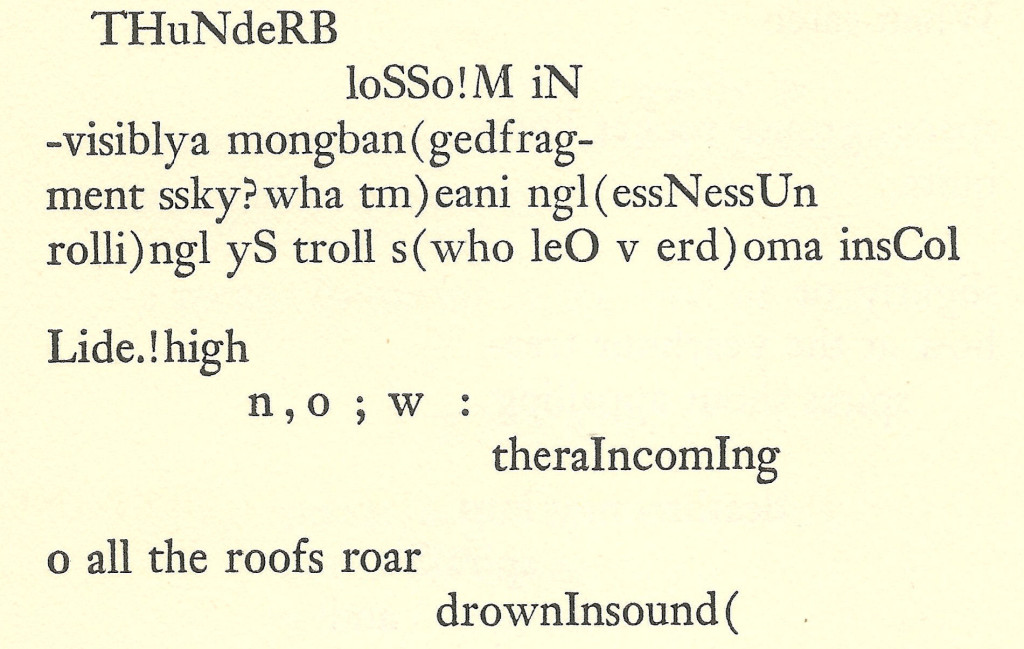

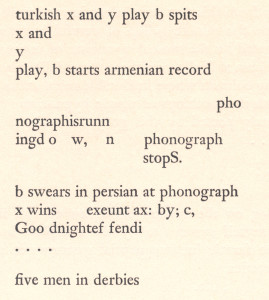

v o i c e o ver (whi!tethatr?apidly legthelessne sssuc kedt oward black,this )roUnd ingrOundIngly rouNdar(round)ounDing ;ball balll ballll balllll — From No Thanks, Section TwoThe message Cummings communicates here — and which langpo types and concrete poets continue to internalize — is remarkably unambiguous: words are toy blocks, and poems, child’s play. No one else has made making it new look so easy.

BG: Actually, this excerpt is from a long evocation of the moon. Easy as rhyming to do, sure.

But Cummings’s poems themselves were only superficially “new.” Beneath the tattoo-thin signifiers of edginess — those lowercase i’s, those words run together — flutters the heart of a romantic. (Is there a correlation between typographically arresting poetry and emotional arrestedness?) He fancies himself an individual among masses, finds the church ladies have “furnished souls,” opposes war. He’s far more self-righteous, this romantic, than any soldier or gossip — and far deadlier: he’s a teenager armed with a journal.

BG: Guriel mentions flaws I also find in Cummings, although I favor individualism and my heart flutters with romanticism. Guriel is an irresponsible critic, however, because he ignores the many poems of Cummings that transcend the attitudes Cummings had and Guriel is superior to. As he would find if he read enough of him to be fair to him.

Recording his thoughts about sex or the female body, however, Cummings’s speaker is less a teenager than a child trapped in a man’s body, which is to say a man-child: a boob blinking at a pair of breasts. In poem after poem, he can’t help but notice such curiosities as “sticking out breasts” and “uttering tits” and “bragging breasts” and “ugly nipples squirming in pretty wrath” and breasts that are “firmlysquirmy with a slight jounce” and “wise breasts half-grown.” (Hands off, ladies! He’s spoken for.) And when he shifts his attention to other parts of the beloved — and, worse, gropes for only the weirdest words to describe them — the boob makes an ass of himself:

i bite on the eyes’ brittle crust

(only feeling the belly’s merry thrust

Boost my huge passion like a businessand the Y her legs panting as they press

proffers its omelet of fluffy lust)

How does one excuse such lines? Is it that you can’t write a poem without breaking some eggs? That you can’t make it new without making a mess?

boys w!ll be boyss, i guess….

BG: It’s easy to excuse, Jason. You merely refer to the many many poor poems of Wordsworth, or to the large dead portions of Pound’s Cantos, and point out that the many world-class poems these two composed are a hundred times more important than any number of their bad ones a cherry-picker like you can find.

.